Use of the Laryngeum Mask for Intubation (Fastrach): Initial Experience in the Specialty Hospital “Dr. Bernardo Sepulveda G”, Centro Medico Nacional Siglo XXI IMSS Mexico

*Corresponding Author(s):

Leopoldo WulffHospital Of Specialties, Instituto Mexicano Del Seguro Social, “Dr. Bernardo Sepúlveda G”, Universidad Nacional Autónoma De México, Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, Mexico

Tel:+58 4143264549,

Email:leowulff@yahoo.com

Abstract

There is unanimous agreement that if planning is done for the management of the airway, the vast majority of complications can be prevented or solved. The American Society of Anesthesiology in recent years has developed an algorithm to follow in case of presenting a difficult and unexpected airway. In this algorithm, various techniques or mechanisms other than direct laryngoscopy are mentioned, which may at a certain moment resolve a pressing situation. The laryngeal mask for intubation (Fastrach) is a device that has increased its popularity by playing an important role in the management of the anatomically difficult airway allowing adequate oxygenation. It offers advantages such as simplicity and versatility in its placement, as well as being a traumatic for the patient. We decided to carry out this project to obtain an initial experience in the management of the airway with this type of devices whose successful results in other countries have not been corroborated in our hospital.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Objective: To demonstrate that the laryngeal mask for intubation (Fastrach) is a useful device for the management of the airway in patients undergoing general anesthesia.

Material and method: We studied 50 patients of both genders and ages between 22 and 85 years, physical status ASA I, II or III, scheduled for elective surgery and general anesthetic technique. The number of attempts of Fastrach placement and orotracheal intubation through it, the time in seconds, the hemodynamic and SpO2 values, and finally the complications during and after the procedure (oral bleeding, impossibility to place Fastrach and/or IOT, odynophagia and/or dysphonia).

Results: A success rate was obtained for the placement of Fastrach and I.O.T. 94% where 54% was the first attempt, 32% the second and 4% the third attempt. The complications presented were minimal and reached 2%.

Conclusion: The use of the laryngeal mask for intubation (Fastrach) as an alternative to direct laryngoscopy for orotracheal intubation in patients with easy airway is feasible and has been shown to be useful, safe and effective.

BACKGROUND

There is unanimous agreement that if a planning is made for the management of the airway of any patient, the vast majority of complications can be prevented or solved.

Although the intubation of the trachea through direct laryngoscopy is the most frequent way to approach the airway, this procedure implies a precise knowledge of the anatomy to be successful during its realization. Adequate visualization of the glottis is not always achieved, so approximately 1% to 3% of cases present difficulty for tracheal intubation and the frequency of failed intubation in 0.05% to 0.2% [1]. In a study of 1,336 patients, García-Guiral et al., reported that 1.4% to 3% of subjects presented difficulty during direct laryngoscopy or tracheal intubation [2]. Other publications show that the difficulty in direct laryngoscopy and intubation is broadly related to the degree of difficulty predicted in the airway.

The American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA), have developed in recent years an algorithm to follow in case of presenting a difficult and unexpected airway. It has submitted modifications according to the experience and needs of the case. In this algorithm, various techniques or mechanisms different from direct laryngoscopy are mentioned that can resolve a pressing situation at a certain moment [3].

Infraglottic application techniques have been developed for the management of the airway of which we can recognize jet ventilation, cricothyroidotomy and tracheostomy. Others are of supraglottic application, such as ventilation with facial mask, Guedel-COPA cannula and Laryngeal Mask (LM). Finally, transglottic application techniques other than orotracheal intubation through direct laryngoscopy and blind digital intubation, blind nasotracheal intubation or guided with direct laryngoscopy, the use of luminous stylet, fibrolaryngoscopy, retrograde intubation and guided intubation through the ML.

The LM it is a device that has increased its popularity by playing an important role in the management of the anatomically difficult airway or for an urgent access to the airway, allowing adequate ventilation and oxygenation of the patient; offers advantages for the simplicity in its placement and its versatility, besides that it is practically atraumatic for the patient. Many studies and cases have been reported in which orotracheal intubation has been successful guided through the LM Pace et al., concluded in their study that, if an orotracheal tube (SOT) is placed unintentionally in the esophagus, the posterior placement of an LM it maintains faster patent airway than reintubation by direct laryngoscopy [4]. Health and Allagain achieved a 90% success by intubating 50 elective patients through LM with a SOT # 6.0 mm [5]. Likewise, Joo and Rose concluded that LM for intubation is an option in the management of the airway followed by failed tracheal intubation or electively in patients with anatomically difficult airways [6].

A great problem arises with this technique, and is the inability to intubate the patient through the Laryngeal Mask (LM) with an orotracheal tube of a caliber greater than 6.5 mm. Due to this, LM was modified in such a way that it not only served to maintain the airway permeable but also could be intubated more easily and with larger caliber orotracheal probes, also eliminating the need to manipulate the head and neck and the insertion of the fingers in the mouth of the patient during his placement.

• An integral 15 mm connector that allows it to be used as the conventional LM avoids accidental disconnections and allows the passage of an SOT 8.0 mm with inflatable sleeve

• A curvature that follows the anatomy of the SOT with which we can avoid the manipulation of the neck, the head and the insertion of the fingers since the pressure against the palate can be applied externally; it also promotes the alignment of the SOT towards the vestibule of the glottis facilitating the insertion of the same through this structure, decreasing the possibility of trauma

• Handle integrated to the LM of intubation which allows a greater and easier handling while holding the device steady during the insertion of the SOT

• V-shaped ramp which sets the SOT towards the center and guiding it anteriorly reducing the risk of trauma to the arytenoid cartilages or the displacement of the tube into the esophagus

• Lifting bar of the epiglottis: a membrane placed in the distal opening of the LM of intubation that keeps the epiglottis out of any possibility of being able to obstruct said opening while protecting and elevating it during the insertion process of the probe [1,7,8]

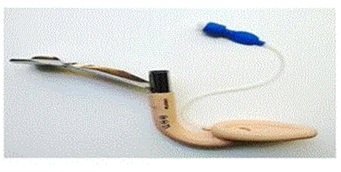

A variety of studies have been conducted with the LM for intubation or “FASTRACH” (Figures 1,2), yielding positive results in almost 100% of these. Langestein and Moller determined that Fastrach improves ventilation compared to the traditional facial mask and duplicates the intubation success through it compared to conventional LM [8]. Joo and Rose obtained 97% success in tracheal intubation in a total of 90 healthy women, ASA I or II physical status [9].

Another study by Langestein and Moller showed that you could intubate blindly with 90% success and of these, 50% are achieved in the first attempt [10]. Kapila et al., using the Fastrach and fibrolaryngoscope achieved 93% success intubation [11]. Similarly, Fukutome et al., achieved 93% success intubation in patients with known difficult airway [12]. Shung et al., achieved a 100% success of the sample studied, performing an intubation through Fastrach in awaken patients with known difficult airway [13]. YW Chan et al., managed to perform blind intubations through Fastrach in 97% of the patients studied, 50% on the first attempt, 42% on the second attempt and 5% on the third attempt. These authors refer that part of the success lies in placing the handlebar of Fastrach in the direction of the intubatore, in an extension maneuver, which facilitates the location of the device so that the possibility of intubation is greater in a second attempt [14].

An important consideration is represented by the output of the conventional probe in its displacement within Fastrach because when it reaches the distal opening thereof it must maintain an angle of approximately 35º with respect to the plane of the inflatable portion of the Fastrach that makes the laryngeal seal, with the purpose of improving the alignment of this probe without pre-established curvature and with the tip of silicone, which in several studies has shown efficacy for intubation through the Fastrach since it manages to maintain that angle of approximately 35º. A disadvantage in the use of this special intubation probe through Fastrach is represented by its cost. Joo and Rose report three clinical cases of difficult airway effectively resolved with this technique. It is significant that in the third published case, they placed the conventional probe with the concavity opposite to that of the Fastrach, so that there is a displacement of the probe with its concavity in contact with the convex portion inside the device. This allowed the researchers to achieve an alignment of the probe at approximately 35°.

Because of the characteristics of our hospital in always being at the forefront of national medicine, we decided to carry out this project to obtain an initial experience in the management of the airway with the laryngeal mask for intubation or Fastrach, a device recently available to us and whose successful results in Europe, Asia and USA have not been corroborated in our population.

OBJECTIVE

Demonstrate that the laryngeal mask for intubation (Fastrach) is a useful device for the management of the airways in patients undergoing general anesthesia.

MATERIAL, PATIENT AND METHODS

Research design

Cuaxi experimental, prospective, longitudinal and descriptive study

Working universe

Description of the variables

Independent variables: Laryngeal mask for intubation (Fastrach) and orotracheal tube SOT.

They are qualitative variables, with a dichotomous qualitative measurement scale. Demographic (gender, age, weight, height); Predictive (physical condition according to ASA, assessment of the airway according to Mallampati classification, Patil or others); Operative Respiratory and hemodynamic.

Sample selection

• Sample size: 50 patients

Selection criteria

Patients who agreed to participate in the study. Patients of either gender scheduled for elective surgery. Patients scheduled for General Anesthesia.

• Patients physical condition ASA I, ASA II or ASA III

• Ages between 20 and 85 years old

Patients who presented a predictive index for adequate mouth opening patients with pathology of the respiratory system.

Patients with risk of regurgitation or bronchoaspiration (previous surgeries of the upper gastrointestinal tract, hiatal hernia, gastroesophageal reflux, ulceropeptic disease and those patients who have not fulfilled fasting correctly).

• Patients with oral or pharyngeal tumors

• Patients with a surgical history of tracheotomy and/or laryngeal surgery

• Patients who had a history or risk of infection by hepatitis virus, cytomegalovirus, HIV

• Impossibility of placement of the Laryngeal Mask for Intubation (Fastrach) and OT intubation on the third attempt.

Procedure

The conventional sterile orotracheal (SOT) probe, after been assured the proper functioning of the insufflation cuff, was also fully lubricated to allow friction-free sliding within the Fastrach. Probes with internal diameter # 7.0 mm and # 7.5 mm were used according to the Fastrach size; the slider of the SOT was also lubricated.

For the placement of the Fastrach, the operator was placed at the head of the surgical bed which was at an average height with respect to said operator. Taken the Fastrach (with its sleeve completely deflated) with the dominant hand and by means of its metal handle, it was inserted into the mouth and moved distally, passing through the isthmus of the jaws until it was felt the lace at the level of the larynx, at which time the cuff was inflated to the volume stipulated for each number used (a maximum of 20 ml for Fastrach # 3). Once the Fastrach cuff was inflated, the hemodynamic and SO2 represented as T3 were measured again. It was verified with the thoracic expansibility and auscultation of respiratory sounds that the airway remains patent, which translated the success in the placement of the Fastrach.

Subsequently, orotracheal intubation was performed through the Fastrach. The SOT conventional was introduced into the Fastrach, with the convexity of it in alignment with the convexity of the Fastrach, in such a way that both surfaces (concave of the SOT and convex of Fastrach) make contact to the extent that the SOT moves within it. The ventilation circuit of the anesthesia machine was connected to the probe to ensure ventilation of the patient during orotracheal intubation attempts. Success in intubation was achieved once the distal end of the SOT come out through the distal end of the Fastrach and cross the glottic vestibule, evidencing itself in the expandability of the thorax and the auscultation of respiratory noises. The connector that each probe has at the proximal level was removed to allow a complete displacement of it through the Fastrach. The slider of the SOT to push it distally and then the Fastrach was removed with the dominant hand, with its cuff deflated and simultaneously the position of the probe was secured to avoid extubation.

If the orotracheal intubation is not possible at the first attempt, a maneuver was performed which consists in pushing the handlebar of the Fastrach towards the operator in order to replace it and a new intubation attempt will be made. If success is not achieved, a third attempt is made by performing a second maneuver consisting of moving the handlebar of the Fastrach distally from the operator. In case of failure, the patient was ventilated through Fastrach, before deflating the cuff and proceeds to orotracheal intubation, through direct laryngoscopy.

The hemodynamic and saturation values of O2 were measured one minute after the end of orotracheal intubation, taking values only when intubation was successful through Fastrach, values that we call T4. The time of Fastrach placement and the successful intubation time was measured (independently if it was achieved in the first, second or third attempt). The intubation time was ruled out if it was failed and if direct laryngoscopy had to be performed. It was taken as total time the period from the moment the operator takes the Fastrach until a successful intubation is performed.

Likewise, it was analyzed if there was oral bleeding, laceration of the mucosa, selective intubation or impossibility of intubation during or after the procedure. One hour and twenty-four hours after the surgical intervention was completed, it was analyzed whether the patient presented odynophagia (sore throat) and/or dysphonia (hoarseness), using the visual analogue scale (VAS), where 0 indicates absence of pain or hoarseness and 10 the worst pain or hoarseness the patient could imagine. Dysphonia/odynophagia when presented was indicate in the postoperative mediate pharmacaine 10% ®solution topical spray used.

Statistical analysis

• Statistical significance was established when the value of p was less than 0.05

RESULTS

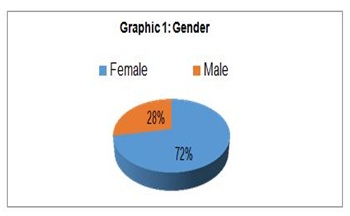

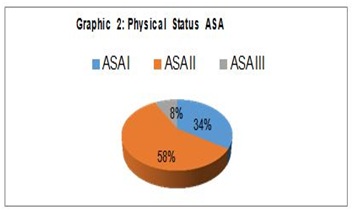

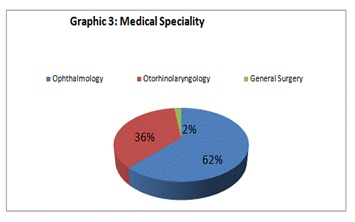

The sample size resulted in 50 patients, 36 females (72%) and 14 males (28%) (Graph 1). The age between 85 and 22 years (average 50.78), the average weight in Kg was 65.84 with a maximum of 86 and a minimum of 40. The height average in meters was 1.57 with a maximum of 1.72 and a minimum of 1.46 (Table 1). Physical status ASA I in 17 patients (34%), ASA II in 29 patients (58%) and ASA III in 4 patients (8%) (Graph 2), where 31 ophthalmology patients (62%), 18 otorhinolaryngology patients (36%) and 1 general surgery patient (2%) (Graph 3).

Figure 1: The Laryngeal mask for intubation(Fastrach).

Figure 2: The Laryngeal mask for intubation(Fastrach).

Graph 1: Gender.

Graph 2: Physical Status ASA.

Graph 3: Medical Speciality.

|

Age |

Size |

Weight |

|

|

Maximum |

85.0 |

1.72 |

86.0 |

|

Minimum |

22.0 |

1.46 |

40.0 |

|

Average |

50.8 |

1.57 |

65.8 |

|

Mode |

58.0 |

1.54 |

65.0 |

|

Number of times |

4.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

|

Standard Deviation |

1.9 |

0.7 |

9.5 |

Table 1: Quantitative variables and statistical analysis.

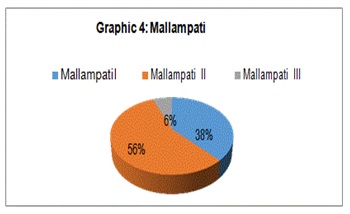

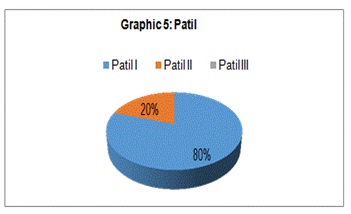

The predictive index for airway assessment was measured according to the adequacy of oral opening (100% of patients), Mallampanti I in 19 patients (38%), II in 28 patients (56%) and III in 3 patients. (6%), there was no IV (0%). Patil I in 40 patients (80%) and II in 10 patients (20%), there was no III (0%). Bell house-Dore I in 50 patients (100%) (Graphs 4,5).

Graph 4: Mallampati.

Graph 5: Patil.

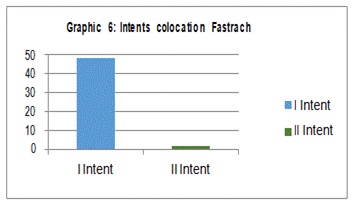

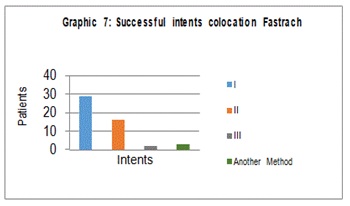

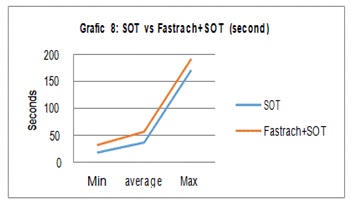

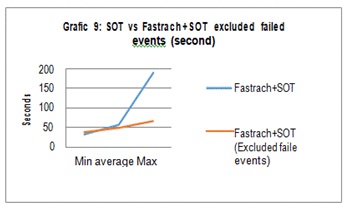

The Fastrach used was # 3 in 100% of the cases. The placement of Fastrach at the first attempt was successful in 48 patients (96%), in the second attempt in 2 patients (4%) (Graph 6). The average time the for the Fastrach placement was 20.2 seconds with a maximum of 30 and a minimum of 15. The SOT used was 7.0 mm in 12 patients (24%) and 7.5 mm in 38 patients (76%). The placement of the SOT in the first attempt was successful in 29 patients (58%), in the second attempt 16 patients (32%) and in the third attempt was placed in 2 patients (4%). In 3 patients (6%) it was necessary to intubate them with direct laryngoscopy at the first attempt. The average time in seconds for the placement of the SOTwas 36.9 seconds (Graph 7) with a maximum of 171 and a minimum of 18. The total time (Fastrach + SOT) average, including the failed events, was 57.0 with a maximum of 192 and a minimum of 38. Excluding failed events the average decreased to 49.1 with a maximum of 67 and a minimum of 38 (Graphs 8,9).

Graph 6: Intents colocation fastrach.

Graph 7: Successful intents colocation fastrach.

Graph 8 : SOT vs Fastrach+SOT (second).

Graph 9 : SOT vs Fastrach+SOT excluded failed events (second).

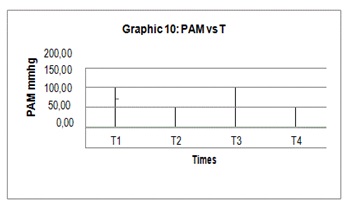

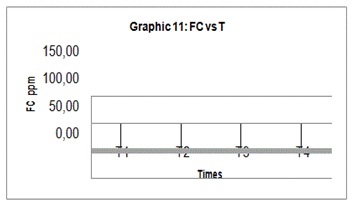

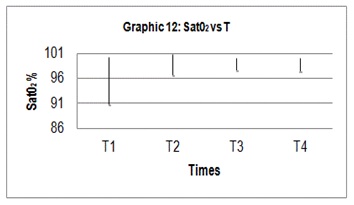

The hemodynamic behavior was assessed based on three parameters (MAP, FC, Sat O2%), with measurements in the four aforementioned times (T1, T2, T3, T4) and the average and standard deviation of these were analyzed (Graphs 10-12), (Table 2).

|

|

PAM |

FC |

SAT |

|||

|

Average |

Standard Deviation |

Average |

Standard Deviation |

Average |

Standard Deviation |

|

|

T1 |

106.8 |

18.07 |

76.2 |

12.25 |

95.34 |

2.42 |

|

T2 |

87.92 |

16.49 |

70.74 |

12.45 |

98.48 |

1.07 |

|

T3 |

86.24 |

19.37 |

71.6 |

11.67 |

98.72 |

0.67 |

|

T4 |

87.04 |

15.47 |

71.86 |

10.08 |

98.56 |

0.67 |

Table 2: The hemodynamic behavior.

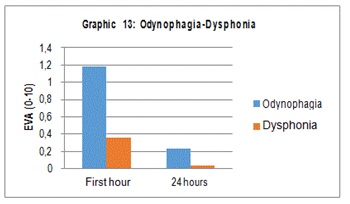

Complications during the procedure were assessed according to slight bleeding evidenced when the Fastrach was removed in 1 patient (2%) and absent in the remaining 49 patients (98%). There was no evidence of mucosal laceration in any of the patients and the success of the Fastrach placement was 100% of the cases. The Impossibility of Orotracheal Intubation (IOT) occurred in 3 patients (6%), being successful in the remaining 47 patients (94%). One thing to be mentioned is that an SOT was docked to the glottis and later mobilized by direct laryngoscopy (2%). Odynophagia at the 1st and 24 hours after the procedure were assessed by EVA (0-10) with an average of 1.18 and 0.24 respectively. Dysphonia was also assessed by EVA (0-10) at the 1st and 24 hours with an average of 0.36 and 0.04 respectively (Graph 13).

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The management of the airway is one of the primary objectives in an anesthetic event. In order to achieve this goal, the anesthesiologist must manage the airway in such a way that it remains patent in a continuous way to achieve an adequate gas exchange. Among the different techniques described for the management of the airway, the use of the laryngeal mask for intubation (Fastrach) is considered a useful, safe and effective alternative.

DISCUSSION

The results of this feasibility study have shown that, in patients of both genders with predictive index of non-difficult airway, the laryngeal mask for intubation (Fastrach) can be used successfully for oxygenation and ventilation. Likewise, orotracheal intubation through the Fastrach has shown an index of success similar to those found in the reviewed literature. In our study we found a success rate of 94%, where 58% was achieved at the first attempt, 32% at the second attempt and 4% at the third attempt. Joo and Rose obtained 97% success, where 90% went to the first attempt, 6.7% to the second and 3.3% to the third. Likewise, Langestein and Moller reported to 90% success rate where 50% went to the first attempt. In the study published by YW Chang reported to 97% success where 50% went to the first attempt.

We can also mention that the hemodynamic behavior measured four times was showed by the patients during placement and intubation through the laryngeal mask for intubation, showed no statistically significant differences (p less than or equal to 0.05).

The postoperative assessment of pain manifested by odynophagia and dysphagia at the 1st and 24th hours of the procedure assessed by Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) showed lower rates in our group when compared with the results obtained by Joo and Rose (1st hour odynophagia 1.18 vs. 4.0 and at 24 hours 0.24 vs. 1.0); (dysphonia 1st hour 0.36 vs. 4.5 and at 24 hours 0.04 vs. 0.5) and its statistical significance showed no difference (p less than or equal to 0.05); we understand that the assessment of pain is subjective compared in ethnic and racial groups.

Our success rate and minimal complications, with no bleeding after the removal of Fastrach in one patient and SOT on the vocal cords after the removal of Fastrach in another patient, can be attributed to the uniformity of our population, with pathways without structural alterations.

There are authors who have defended the use of the laryngeal mask for intubation (Fastrach) in patients with difficult airway. In the consulted bibliography there are a limited number of successful clinical cases of intubation tracheal with Fastrach in patients with difficult airways. Therefore, we cannot defend or oppose the use of Fastrach in a patient with a difficult airway until more evidence is available on its effectiveness. However, we suggest the need to become familiar with Fastrach in patients with an easy airway before attempting its use in patients with difficult airway.

Finally, it would be important to highlight the need to continue studies aimed at comparing the usefulness and efficacy of this device with other frequently used in the management of the airway such as laryngoscopy and to make a comparative study showing its advantages and disadvantages.

CONCLUSION

The use of the laryngeal mask for intubation (Fastrach) as an alternative to direct laryngoscopy for orotracheal intubation in patients with easy airway is feasible and has proven to be useful, safe and effective.

The hemodynamic behavior shown and the discomforts or complications after the procedure compared between the male and female groups did not show statistically significant differences.

We suggest the need to become familiar with the use of this device by using it in patients with easy airway before attempting its use in patients with difficult airway.

REFERENCES

- Brain AIJ, Verghese C, Addy EV, Kapila A, Brimacombe J (1997) The intubating laryngeal mask II: a preliminary clinical report of a new means of intubating trachea. Br J Anaesth 79: 704-709.

- García-Guiral M, García-Amigueti F, Ortells-Polo MA, Muiños-Haro P, Gallego-Gonzalez J, et al. (1997) Relationship between laryngoscopy degree and intubation difficulty. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 44: 93-97.

- Benumof J (1998) The ASA difficult airway algorithm: New thouths/considerations. ASA, Annual Refresher Couse Lectures, USA. Pg No: 236.

- Pace NA, Gajraj NM, Pennant JH, Victory RA, Johnson ER, et al. (1994) Use of the laryngeal mask airway after oesophageal intubation. Br J Anaesth 73: 688-689.

- Heath ML, Allagain JJ (1991) Intubation through the laryngeal mask. A technique for unexpected difficult intubation. Anaesthesia 46: 545-558.

- Joo HS, Rose DK (1998) Fastrach--a new intubating laryngeal mask airway: successful use in patients with difficult airways. Can J Anaesth 45: 253-256.

- Brain AIJ, Verghese C, Addy EV, Kapila A (1997) The intubating laryngeal mask. I: development of a device for intubation of the trachea. Br J Anaesth 79: 699-703.

- Langenstein H, Möller F (1998) First experience with the laryngeal intubation mask. Anaesthesist 47: 311-319.

- Joo HS, Rose DK (1999) Mascarilla laríngea de intubación con o sin guía de fibra óptica. Anesth Analg 2: 202-207.

- Langestein H, Moller F (1998) Intubating laryngeal mask. Anaesthesiol Reanim 23: 41-42.

- Kapila A, Addy EV, Verghese C, Brain AIJ (1997) The intubating laryngeal mask airway: an initial assessment of performance. Br J Anaesth 79: 710-713.

- Fukutome T, Amaha K, Nakazawa K, Kawamura T, Noguchi H (1998) Tracheal intubation through intubating laryngeal mask airway (LMA-Fastrach) in patients with difficult airways. Anaesth Intensive Care 26: 387-391.

- Shung J, Avidan MS, Ing R, Klein DC, Pott L (1998) Awake intubation of the difficult airway with the intubating laryngeal mask airway. Anaesthesia 53: 645-649.

- Chan YW, Kong CF, Kong CS, Hwang NC, Ip-Yam PC (1998) The intubating laryngeal mask airway (ILMA): initial experience in Singapore. Br J Anaesth 81: 610-611.

Citation: Wulff L, Puente MA, Castellanos A, Déctor T (2018) Use of the Laryngeum Mask for Intubation (Fastrach): Initial Experience in the Specialty Hospital “Dr. Bernardo Sepulveda G”, Centro Medico Nacional Siglo XXI IMSS Mexico. J Anesth Clin Care 5: 28.

Copyright: © 2018 Leopoldo Wulff, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.