ABSTRACT

Background

Retained Common Bile Duct (CBD) stones are a complication occasionally seen after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Post-operative Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography(ERCP) with removal of the retained CBD stone is usually the procedure of choice. We present a case of retained CBD stone after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Postoperatively, the case was complicated with bile leakage from the cystic duct stump due to backpressure from a retained CBD stone. ERCP with removal of the retained stone failed due to an anatomic variation of the CBD. A parallel tubular structure, mimicking a duplicate CBD at the supraduodenal portion of the extrahepatic ductal system was identified on abdominal Computed Tomography (CT). The patient was treated by open choledocholithotomy for stone removal and T-tube insertion, and had an uncomplicated postoperative course. The anatomical variation seen in this case has not been previously described in the surgical literature, and we believe awareness of this variation, which can result in postoperative complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, is warranted.

KEYWORDS

Anatomical variations; Bile leakage; Cholecystitis; Cystic duct; Laparoscopic cholecystectomy; Hepatic duct

Abbreviations

CBD: Common Bile Duct

CT: Computed Tomography

ENBD: Endoscopic Nasobiliary DrainageERCP: Endoscopic Retrograde CholangiopancreatographyHIDA: Hepatobiliary Iminodiacetic AcidIOC: Intra-Operative CholangiographyMRCP: Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography

Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has a low morbidity rate, though the procedure is associated with certain complications. Bile duct injuries, including leaks and strictures, are a serious complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy with a reported incidence of 0.5-0.6% [1]. Bowel injury has a reported incidence of up to 0.87% [2], and while the rate of vascular injury is uncertain, the rate of right hepatic artery injury among patients with bile duct injury has been reported to be 12% [3].

A thorough understanding of biliary anatomy is extremely important in hepatobiliary surgery [4], however, normal biliary anatomy is thought to be present in only 58% of the population [5]. Anatomic variations, including anomalies of the cystic duct and the hepatic duct, are major causes of bile duct injuries and complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy [6-8]. Therefore, altering the surgical technique due to an anatomic variation is not uncommon [9]. However, despite attention and precaution, preoperatively unidentified biliary anomalies will be found during surgery and can complicate the clinical course of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

We herein report the case of a patient with acute cholecystitis that underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy and was found to have an anatomical variation of the extrahepatic ductal system mimicking a duplicate Common Bile Duct (CBD), combined with an impacted biliary tree calculous.

Case Report

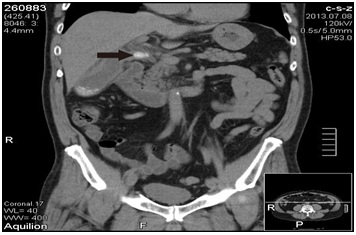

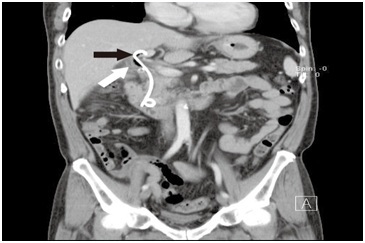

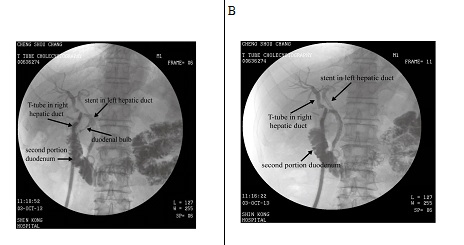

A 58-year-old male without history of underlying systemic disease was seen with a chief complaint of sudden onset of moderate to severe right upper quadrant abdominal pain that began 7 days prior. The pain was intermittent, and aggravated by eating. He did not have a fever, and laboratory studies revealed no hyperbilirubinemia. Abdominal Computed Tomography (CT) was consistent with acute cholecystitis with impacted cystic duct stones (Figure 1). Abdominal ultrasound findings were consistent with those of the CT scan. At our institution a Hepatobiliary Iminodiacetic Acid (HIDA) scan is not routinely performed, and was not done in this case.The patient was admitted and laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed that day. At surgery, severe inflammation with a thick gall bladder wall and surrounding fibrosis were noted. The procedure was performed without complications, and there was no iatrogenic bile duct injury. On postoperative day 1, bilious leakage was noted from the drain tube. On postoperative day 2, Endoscopic Nasobiliary Drainage (ENBD) was performed first, followed by Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) which identified the site of bile leakage as the cystic stump. In this case, since the leakage was well drained without toxic sign, the patient was treated conservatively using parenteral antibiotics. Stone retrieval failed due to an unexpected filling defect that was not from a calculus, and was most likely due to external compression (which later proved to be an impacted stone in the diseased right hepatic bile duct). Three days later (postoperative day 6), ERCP was repeated, but again failed. One plastic stent was placed in the common bile duct without complication, and the patient was observed. Abdominal CT was performed on postoperative day 27 to confirm the location of the stent, and it was found that the stent was placed in a normal caliber variated left hepatic duct that was parallel to a right dilated duct with one stone impacted at the level distal to cystic duct confluence (Figure 1). Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was not performed because we believed the biliary system was not interrupted during surgery. Based on the imaging study, dual extrahepatic tubular structures with an ultra-low insertion of the right and left hepatic duct was considered likely.Due to the difficulty in performing an endoscopic procedure, open choledocholithotomy for stone removal and T-tube insertion was performed on day 31 after the laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 7 (38 days after laparoscopic cholecystectomy). Cholangiography performed 3 weeks later demonstrated that the T-tube and stent were placed in 2 separate parallel ducts, and confluence was at the retro-duodenal area 1-2 cm above the intra-pancreatic portion of common bile duct (Figure 2). The angle of the confluence was very sharp, which we believed was the reason the endoscopic procedure failed. The T-tube was removed 4 weeks after choledocholithotomy, and the patient is disease free at 3 years after surgery.

Discussion

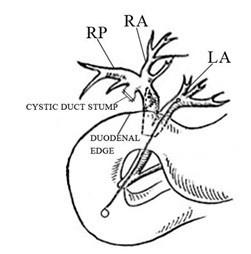

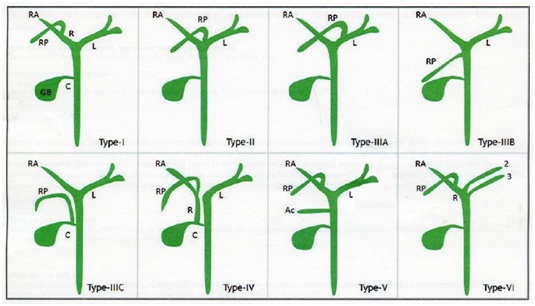

In this report we described a unique anatomical variation of the extrahepatic ductal system; specifically a dual tubular structure at the supra-duodenal level, mimicking a duplicate CBD. Such anatomical variation has not been reported in the current surgical literature. In this case, the anatomical variation was suspected after postoperative ERCP, and confirmed via abdominal CT. While the variation may have been identified by preoperative MRCP, it is not commonly performed as a first line imaging study for acute calculous cholecystitis [10]. While the possibility of this anatomical variation is known, to the best of our knowledge it has not been reported in the current surgical literature and thus the incidence is unknown. Thorough knowledge of biliary anatomy is critically important for hepatobiliary surgery, and variations are of great significance when performing surgical intervention of the hepatobiliary system or cholecystectomy. Perioperative identification of cystic and bile duct variants, especially right hepatic duct variants, can avoid injury to the cystic duct and common bile duct [11,12]. Various techniques are available for visualization of the biliary tree such as intravenous cholangiography, ERCP, and MRCP [11,12]. Unfortunately, the majority of patients that undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy have only preoperative ultrasonography, and most biliary anomalies are diagnosed during or after surgery. Although in most cases complications and injuries can be treated with subsequent endoscopic procedures [12-14], in complex cases and those with rare anomalies such as in the present case salvage procedures can be very complicated. In our case, when biliary leakage was found after the laparoscopic cholecystectomy some surgeons may have chosen MRCP as the examination of choice [15]. We instead performed ERCP because it allows both diagnosis and treatment. Although MRCP is better for diagnosis, it does not allow treatment of biliary tree stones. ERCP revealed bile leakage from cystic duct stump. A stent was then intended to be inserted in the CBD for biliary drainage. However, abdomen CT performed after ERCP revealed the stent was located in the left hepatic duct. Follow up post operative T tube cholangiography confirmed dual tubular extrahepatic structures. This particular anatomical variation could not be identified during ERCP because cannulation of the diseased right hepatic duct was not possible due to angulation from the anatomic variation. Diagramatic illustration of anatomical variation of the current case and common variants of the right hepatic duct are illustrated in figure 3. Based on CT and ERCP imaging, we believe that our patient had a type IV variant [11] combined with an dual extrahepatic bile ducts with ultra-low ductal insertion.Moreover, an impacted biliary tree stone at a level distal to the cystic duct and right posterior duct confluence, combined with the unusually low extrahepatic bile duct insertion, made treatment even more difficult. Although an endoscopic procedure is advocated for post-cholecystectomy retained biliary tree stones, our experience implies that anatomical variations may make endoscopic procedures more difficult and increase the failure rate.Imaging studies that can assist in preoperative anatomical evaluation include helical CT cholangiography and MRCP [11,12]. Intra-Operative Cholangiography (IOC) can also help identify anatomical variations [10,11]. However, in actual practice most patients only have preoperative abdominal sonography due to limitations of healthcare resources and insurance restrictions. Jaundice or dilatation of the biliary tree may suggest cholelithiasis, but anatomic variations usually do not result in different presenting symptoms. Therefore, clinical suspicion and appropriate imaging studies are essential for an accurate preoperative diagnosis. Special imaging studies can surely improve the accuracy of diagnosis, but, careful and expert interpretation is also extremely important for obtaining an accurate diagnosis.Experience in dealing with difficult cases greatly contributes to clinical practice. The current case reminds us that rare and unique anatomical variations occur in the biliary system and can complicate the treatment of cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis. The biliary system should always be carefully examined on preoperative imaging studies and intraoperatively, and any suspicion of an anatomical variant should be examined with appropriate imaging studies. Surgeon awareness of any suspected anatomical variant is mandatory in order to avoid bile duct injury.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Figures

Figure 1A:Abdominal Computed Tomography (CT) on admission was consistent with acute cholecystitis with impacted cystic duct stones. Black arrow: stone impacted in the cystic duct.

Figure 1B: Abdominal CT performed on postoperative day 27 to confirm the location of the stent. The stent was found placed in a normal caliber bile duct that was parallel to a dilated duct with one stone impacted at the level distal to cystic duct confluence. Black arrow: Stent in the left hepatic duct. A parallel tubular structure (white arrow) was seen adjacent to the left hepatic duct at the supraduodenal level.

Figure 2: A,B) Postoperative T-tube cholangiography showed a dual tubular structure at the supra-duodenal level. Note that the duodenal bulb is visible in image A.

Figure 3A: Diagramatic presentation of the anatomic variation in this patient.

Figure 3B: Main variations of the right biliary duct system [11].