Journal of Clinical Studies & Medical Case Reports Category: Medical

Type: Case Report

Sepsis Due to Deep Posterior Neck Abscesses Secondary to Prevotella bivia: Beware of Emerging Opportunistic Pathogens

*Corresponding Author(s):

Omar DannerDepartment Of Surgery, Morehouse School Of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, United States

Tel: +1 4046161415,

Fax:+1 4046161417

Email:odanner@msm.edu

Received Date: Jul 17, 2019

Accepted Date: Aug 05, 2019

Published Date: Aug 12, 2019

Keywords

Prevotella bivia; Opportunistic Pathogens; Hidradenitis Suppurativa

INTRODUCTION

Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS), also known as acne inversa, is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder usually associated with apocrine glands characterized by recurrent painful inflammatory nodules, pustules, abscesses, and scars [1]. It is believed to result from occlusion of the terminal hair follicles due to hyperkeratosis. Subsequent follicular rupture with secondary infection leads to persistent inflammation and a granulomatous reaction with resulting chronic sinus tracts with scarring. Eccrine gland ducts empty directly onto the skin surface whereas apocrine glands empty into the follicular canal. It therefore follows that plugging by hyperkeratosis would have more dire consequences in the apocrine glands [2].

Typically, it develops in intertriginous areas, such as the axilla, inguinal, anogenital, inframammary regions, and less commonly the nape of the neck [1-3]. Predisposing factors include obesity, diabetes mellitus and cigarette smoking. The predominant microorganisms isolated from patients with HS are usually gram-positive cocci, with the staphylococcus species being the most common [4]. However, few reports of Prevotella bivia isolated from abscesses involving the posterior neck have been described [4,5].

Prevotella species, once part of the Bacteriodes genus, are small anaerobic gram-negative rods frequently identified in different regions of the head and neck when the microbiome of the region is elucidated using deep sequencing techniques [6]. The species of Prevotella most often associated with causing diseases in humans are P. intermedia, P. bivia, P. melaninoge (nica), P. nigrescens and P. disiens [7,8]. P. bivia, is usually found in vaginal and oral flora. Prevotella species have also been implicated in chronic sinusitis, middle ear infections, brain abscesses and intra abdominal abscesses [9].

There are multiple scoring systems used to evaluate and stage HS. The most common and practical is the Hurley classification, which consists of three stages:

Stage I: Single or multiple isolate abscess without any scarring or sinus tracts

Stage II: Recurrent single abscess or multiple widely separated lesions with formation of sinus tracts

Stage III: Diffuse and broad involvement across a regional area with multiple interconnected sinus tracts and abscess

Other scoring systems exist and include the Sartorius score, Physician Global Assessment (PGA) score and the Hidadenitis Suppurativa Severity Index (HSSI). These are more utilized in clinical studies and trials to provide more objective comparisons of management options (Ref).

The deep neck spaces are potential spaces separated by fascial planes. They include submandibular, masticator, parotid, parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal (danger), prevertebral and anterior visceral space. Deep neck abscesses are less frequent today possibly due to more timely administration of effective antibiotics. When poorly managed, they can lead to life-threatening complications. They most commonly arise secondary to dental, and sometimes oropharyngeal, infections. Less commonly, salivary gland infections may be causative.

HS involving the nape of the neck has not previously been associated with deep neck infections. Most infections are superficial and polymicrobialin nature with Staphylococcus aureus and streptococcus viridans being the predominant gram-positive microorganisms. However, Klebsiella pneumoniae is more frequently isolated in diabetics particularly in Asia. Complications resulting from deep neck abscesses may be local such as mediastinitis, empyema, pericarditis, carotid artery rupture and jugular venous thrombosis. More distal or systemic involvement manifest as cavernous sinus thrombosis, septic emboli, and multisystem organ dysfunction. Typically, the infection involves one deep space adjacent to the index site, the submandibular and para-pharyngeal spaces being the most affected. However, multiple spaces may be involved from contiguous spreaddueto HS of the posterior neck, which can be extensive and requires surgical drainage and skin debridement [10,11]. Purulent effluent from the abscess typically yields microbiological cultures consistent with normal skin flora [11,12]. Similar to most HS lesions, deep neck infections are poly-microbial in nature [13]. The most frequently cultured bacteria from HS lesions are Gram-positive cocci and rods, such as coagulase negative Staphlococci and Corynebacterium, as well as various subspecies of anaerobic bacteria [11,12]. Although they are uncommon, HS abscesses due to Prevotella bivia may be associated with a more aggressive for of deep infection and thereby lead to sepsis, which must be recognized early and effectively treated with a combination of surgical drainage and appropriate antibiotic coverage to prevent progression to septic shock, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and death.

Typically, it develops in intertriginous areas, such as the axilla, inguinal, anogenital, inframammary regions, and less commonly the nape of the neck [1-3]. Predisposing factors include obesity, diabetes mellitus and cigarette smoking. The predominant microorganisms isolated from patients with HS are usually gram-positive cocci, with the staphylococcus species being the most common [4]. However, few reports of Prevotella bivia isolated from abscesses involving the posterior neck have been described [4,5].

Prevotella species, once part of the Bacteriodes genus, are small anaerobic gram-negative rods frequently identified in different regions of the head and neck when the microbiome of the region is elucidated using deep sequencing techniques [6]. The species of Prevotella most often associated with causing diseases in humans are P. intermedia, P. bivia, P. melaninoge (nica), P. nigrescens and P. disiens [7,8]. P. bivia, is usually found in vaginal and oral flora. Prevotella species have also been implicated in chronic sinusitis, middle ear infections, brain abscesses and intra abdominal abscesses [9].

There are multiple scoring systems used to evaluate and stage HS. The most common and practical is the Hurley classification, which consists of three stages:

Stage I: Single or multiple isolate abscess without any scarring or sinus tracts

Stage II: Recurrent single abscess or multiple widely separated lesions with formation of sinus tracts

Stage III: Diffuse and broad involvement across a regional area with multiple interconnected sinus tracts and abscess

Other scoring systems exist and include the Sartorius score, Physician Global Assessment (PGA) score and the Hidadenitis Suppurativa Severity Index (HSSI). These are more utilized in clinical studies and trials to provide more objective comparisons of management options (Ref).

The deep neck spaces are potential spaces separated by fascial planes. They include submandibular, masticator, parotid, parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal (danger), prevertebral and anterior visceral space. Deep neck abscesses are less frequent today possibly due to more timely administration of effective antibiotics. When poorly managed, they can lead to life-threatening complications. They most commonly arise secondary to dental, and sometimes oropharyngeal, infections. Less commonly, salivary gland infections may be causative.

HS involving the nape of the neck has not previously been associated with deep neck infections. Most infections are superficial and polymicrobialin nature with Staphylococcus aureus and streptococcus viridans being the predominant gram-positive microorganisms. However, Klebsiella pneumoniae is more frequently isolated in diabetics particularly in Asia. Complications resulting from deep neck abscesses may be local such as mediastinitis, empyema, pericarditis, carotid artery rupture and jugular venous thrombosis. More distal or systemic involvement manifest as cavernous sinus thrombosis, septic emboli, and multisystem organ dysfunction. Typically, the infection involves one deep space adjacent to the index site, the submandibular and para-pharyngeal spaces being the most affected. However, multiple spaces may be involved from contiguous spreaddueto HS of the posterior neck, which can be extensive and requires surgical drainage and skin debridement [10,11]. Purulent effluent from the abscess typically yields microbiological cultures consistent with normal skin flora [11,12]. Similar to most HS lesions, deep neck infections are poly-microbial in nature [13]. The most frequently cultured bacteria from HS lesions are Gram-positive cocci and rods, such as coagulase negative Staphlococci and Corynebacterium, as well as various subspecies of anaerobic bacteria [11,12]. Although they are uncommon, HS abscesses due to Prevotella bivia may be associated with a more aggressive for of deep infection and thereby lead to sepsis, which must be recognized early and effectively treated with a combination of surgical drainage and appropriate antibiotic coverage to prevent progression to septic shock, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and death.

CASE REPORT

The patient is a 21-year-old obese female with a known history of HS of the upper back, axilla, umbilicus, and groin. Eight days prior to presentation, she was seen at an outside facility for a flare up of a posterior neck abscess, which was treated with super facial incision and drainage. She was subsequently discharged home with topical clindamycin treatment. She represented to our emergency department with increasing pain in her posterior neck.

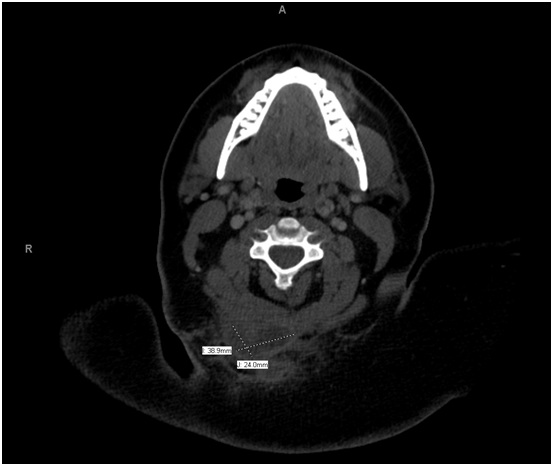

Physical examination was significant for a 3 cm hyper pigmented nodule along the posterior aspect of her neck with multiple sinus tracts along the bilateral axilla, consistent with Hurley Stage III disease. On admission, she had a leukocytosis of 13.9 K/mL. Computed Tomography (CT) of the neck revealed a rim enhancing fluid collection, measuring 3.9 x 2.4 cm, involving the skin and subcutaneous tissues of the right prevertebral neck space, extending down to the trapezius muscle (Figure 1). Given the patient’s history, presentation and imaging, the decision was made to proceed with incision and drainage and debridement of the involved area.

Physical examination was significant for a 3 cm hyper pigmented nodule along the posterior aspect of her neck with multiple sinus tracts along the bilateral axilla, consistent with Hurley Stage III disease. On admission, she had a leukocytosis of 13.9 K/mL. Computed Tomography (CT) of the neck revealed a rim enhancing fluid collection, measuring 3.9 x 2.4 cm, involving the skin and subcutaneous tissues of the right prevertebral neck space, extending down to the trapezius muscle (Figure 1). Given the patient’s history, presentation and imaging, the decision was made to proceed with incision and drainage and debridement of the involved area.

Figure 1: CT Scan Image of a Cervical Soft Tissue Infection with contrast demonstrating a 3.9 x 2.4 cm posterior neck deep space abscess.

An incision was made over the area of maximal fluctuance, and purulent fluid was evacuated from the abscess cavity and cultures were taken. All loculations were broken up and hair noted within the abscess cavity was removed. Attention was then turned to the posterior/superior back abscess, which was incised and drained, releasing approximately 100 mL of purulent fluid. A sample was also sent for culture and sensitivity and grew out Prevotella.

Her postoperative course was uneventful. She was subsequently discharged with twice daily gauze packing and started on a seven-day course of empiric oral clindamycin. Wound cultures revealed P. bivia. Because the minimal inhibitory concentration of antimicrobials to P. bivia are variable, interpretive criteria are not available from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, and sensitivities were not performed. At her 3-week follow-up, examination of her neck wound revealed resolution of erythema and her HS, no drainage or fluctuance, and good granulation tissue.

Her postoperative course was uneventful. She was subsequently discharged with twice daily gauze packing and started on a seven-day course of empiric oral clindamycin. Wound cultures revealed P. bivia. Because the minimal inhibitory concentration of antimicrobials to P. bivia are variable, interpretive criteria are not available from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, and sensitivities were not performed. At her 3-week follow-up, examination of her neck wound revealed resolution of erythema and her HS, no drainage or fluctuance, and good granulation tissue.

DISCUSSION

Changing trends in deep neck abscesses have been described in previous studies [13,14]. With improved recognition, hygiene and better antibiotic coverage, deep neck abscesses have been reported to occur less frequently than in the past [15,16]. Nevertheless, they remain challenging clinical emergencies. Once an abscess occupies one of the deep neck spaces, the infection can spread across the planes and/or damage adjacent vital neurovascular structures. Consequently, these types of infections can progress rapidly and become life threatening medical conditions [15]. In addition to severe sepsis and septic shock, localized respiratory and digestive tract disturbance as well as more serious complications may occur, such as acute airway obstruction, pneumonia, lung abscess, mediastinitis, pericarditis, internal jugular vein thrombosis and carotid artery erosion [14-17].Therefore, delayed recognition and management of deep neck infections and abscesses can result in catastrophic consequences and remains a challenge to surgeons and other physicians who treat this condition [11].

In ourpatient’scase, Hidradenitis (HA) in the intertriginous areas of the posterior neck developed into a deep neck abscess. Abscess cultures from the HA-induced neck disease isolated P. bivia as the pathogen. Virulence mechanisms for Prevotella species include attachment to the mucosa, immune system evasion, and increased production of virulence factors as the microorganism transitions from commensal, in the oral flora, to opportunistic pathogen in the deep space [2,5]. Interestingly, one study demonstrated an increased level of proteolytic activity in pathologic P. intermedia clinical isolates versus those recovered from mouths of healthy subjects [7]. Another important virulence factor in Prevotella species infections is the Exopolysaccharide (EPS). EPS most commonly provides scaffolding for biofilm formation, a critical step in the development of dental caries and periodontal disease. In addition, EPS serves as a capsule that facilitates mucosal adherence and resistance to phagocytosis [18]. Although a direct role of EPS in the development of neck abscess has not been established, we hypothesize that the increased mucosal adherence contributes to the increased damage that P. bivia can cause to aero-digestive structures located in the neck. Although a multicenter study by Toprak et al., demonstrated Prevotella susceptibilities to piperacillin/tazobactam, carbapenems, tigecycline and metronidazole, it is essential to provide early coverage with an appropriate spectrum empiric antibiotic regimen until culture-directed antimicrobial therapy can be initiated given the potential for the aggressive spread of this pathogen.

Combined with adequate surgical drainage of the abscess, antibiotic therapy is essential for successful treatment [12,19-21,23,24]. For effective antimicrobial treatment, microbiologic data on the abscess are essential. However, it usually takes several days or longer to acquire the culture data. Therefore, empiric antimicrobial therapy is frequently initiated before definitive culture results are obtainable. Various empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic regimens have been used successfully in several studies [20-24]. However, due to increasing antibiotic resistance among these emerging pathogensit is important to be aware of the coverage efficacy of different empiric antibiotic regimens [12,20,21].

A retrospective study reviewed 89 culture positive hospitalized patients with deep neck abscesses diagnosed at a tertiary-care hospital over a 5-year period revealed that 89% (89/100) of bacterial cultures yielded positive results [25]. The predominant aerobes were viridans streptococci (37%), Klebsiella pneumonia (23%), and Staphylococcus aureus (11%). The predominant anaerobes included species of Prevotella (17%), Peptostreptococcus (14%) and Bacteroides (14%) [25]. Although the study determined that antimicrobial therapy should ideally be tailored to culture data, the coverage rate of different empiric antimicrobial agents was analyzed as well [25].

Multiple combinations of empiric antibiotics have been tested for the treatment of deep neck abscesses with similar efficacies; they are as follows [20,21,25]:

Regimen 1: Penicillin G, clindamycin and gentamicin

Regimen 2: Ceftriaxone and clindamycin

Regimen 3: Ceftriaxone and metronidazole

Regimen 4: Cefuroxime and clindamycin and

Regimen 5: Penicillin and metronidazole

The coverage rates of regimens 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 were 67.4%, 76.4%, 70.8%, 61.8%, and 16.9%, respectively. Regimen 2 (ceftriaxone and clindamycin) demonstrated the most efficacious antibiotic treatment followed by regimen 3 (ceftriaxone and metronidazole). Regimen 2 was significantly better than regimen 4 (cefuroxime and clindamycin) (p < 0.001). Regimen 2 had better coverage than regimens 1 (p = 0.096) and 3 (p = 0.302), but the difference was not statistically significant [25].

In ourpatient’scase, Hidradenitis (HA) in the intertriginous areas of the posterior neck developed into a deep neck abscess. Abscess cultures from the HA-induced neck disease isolated P. bivia as the pathogen. Virulence mechanisms for Prevotella species include attachment to the mucosa, immune system evasion, and increased production of virulence factors as the microorganism transitions from commensal, in the oral flora, to opportunistic pathogen in the deep space [2,5]. Interestingly, one study demonstrated an increased level of proteolytic activity in pathologic P. intermedia clinical isolates versus those recovered from mouths of healthy subjects [7]. Another important virulence factor in Prevotella species infections is the Exopolysaccharide (EPS). EPS most commonly provides scaffolding for biofilm formation, a critical step in the development of dental caries and periodontal disease. In addition, EPS serves as a capsule that facilitates mucosal adherence and resistance to phagocytosis [18]. Although a direct role of EPS in the development of neck abscess has not been established, we hypothesize that the increased mucosal adherence contributes to the increased damage that P. bivia can cause to aero-digestive structures located in the neck. Although a multicenter study by Toprak et al., demonstrated Prevotella susceptibilities to piperacillin/tazobactam, carbapenems, tigecycline and metronidazole, it is essential to provide early coverage with an appropriate spectrum empiric antibiotic regimen until culture-directed antimicrobial therapy can be initiated given the potential for the aggressive spread of this pathogen.

Combined with adequate surgical drainage of the abscess, antibiotic therapy is essential for successful treatment [12,19-21,23,24]. For effective antimicrobial treatment, microbiologic data on the abscess are essential. However, it usually takes several days or longer to acquire the culture data. Therefore, empiric antimicrobial therapy is frequently initiated before definitive culture results are obtainable. Various empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic regimens have been used successfully in several studies [20-24]. However, due to increasing antibiotic resistance among these emerging pathogensit is important to be aware of the coverage efficacy of different empiric antibiotic regimens [12,20,21].

A retrospective study reviewed 89 culture positive hospitalized patients with deep neck abscesses diagnosed at a tertiary-care hospital over a 5-year period revealed that 89% (89/100) of bacterial cultures yielded positive results [25]. The predominant aerobes were viridans streptococci (37%), Klebsiella pneumonia (23%), and Staphylococcus aureus (11%). The predominant anaerobes included species of Prevotella (17%), Peptostreptococcus (14%) and Bacteroides (14%) [25]. Although the study determined that antimicrobial therapy should ideally be tailored to culture data, the coverage rate of different empiric antimicrobial agents was analyzed as well [25].

Multiple combinations of empiric antibiotics have been tested for the treatment of deep neck abscesses with similar efficacies; they are as follows [20,21,25]:

Regimen 1: Penicillin G, clindamycin and gentamicin

Regimen 2: Ceftriaxone and clindamycin

Regimen 3: Ceftriaxone and metronidazole

Regimen 4: Cefuroxime and clindamycin and

Regimen 5: Penicillin and metronidazole

The coverage rates of regimens 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 were 67.4%, 76.4%, 70.8%, 61.8%, and 16.9%, respectively. Regimen 2 (ceftriaxone and clindamycin) demonstrated the most efficacious antibiotic treatment followed by regimen 3 (ceftriaxone and metronidazole). Regimen 2 was significantly better than regimen 4 (cefuroxime and clindamycin) (p < 0.001). Regimen 2 had better coverage than regimens 1 (p = 0.096) and 3 (p = 0.302), but the difference was not statistically significant [25].

CONCLUSION

HS of the posterior neck is a relatively uncommon cause of deep neck abscess. For effective treatment these cases typically require surgical drainage and complete debridement of the involved skin and soft tissues combined with appropriate antibiotic therapy. Fluid or tissue from the abscess should be sent for microbiological culture and sensitivity testing. Although common pathogens are typically consistent with skin flora P. bivia should be considered as a possible offending pathogen in HA-associated deep neck abscesses. For successful management, early recognition and treatment with proper empiric antibiotics and surgical drainage followed by culture-directed antibiotic therapy is necessary. We recommend using ceftriaxone and clindamycin for initial empiric antibiotic coverage until final culture data is obtained.

REFERENCES

- Fimmel S, Zouboulis CC (2010) Comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa), Dermatoendocrinol 2: 9-16.

- Kurzen H, Kurokawa I, Jemec GB, Emtestam L, Sellheyer K, et al. (2008) What causes hidradenitis suppurativa? Exp Dermatol 17: 455-472.

- Plewig G, Steger M (1989) Acne inversa (alias acne triad, acne tetrad or hidradenitis suppurativa) In: Marks R, Plewig G (ed.). Acne and related disorders. London: Martin Dunitz Page no: 345-357.

- Guet-Revillet H, Coignard-Biehler H, Jais JP, Quesne G, Frapy E et al. (2014) Bacterial pathogens associated with hidradenitis suppurativa, France. Emerg Infect Dis 20: 1990-1998.

- Ring HC, Riis Mikkelsen P, Miller IM, Jenssen H, Fuursted K, et al. (2015) The bacteriology of hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. Exp Dermatol 24: 727-31.

- Finegold SM (1996) Anaerobic Gram-Negative Bacilli. Medical Microbiol (4thend) Ch. 20.

- Ruan Y, Shen L, Zou Y, Qi Z, Yin J, et al. (2015)“Comparative genome analysis of Prevotella intermedia strain isolated from infected root canal reveals features related to pathogenicity and adaptation. BMC Genomics. 16: 122.

- Guet-Revillet H, Jais JP, Ungeheuer MN, Coignard-Biehler H, Duchatelet S, et al. (2017) The Microbiological Landscape of Anaerobic Infections in Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Prospective Metagenomic Study. Clin Infect Dis 65: 282-291.

- Murray TS, Cassese T (2016) Bacteriology of the Head and Neck Region.” Head, Neck, and Orofacial Infections. Chapter 2 Page no: 27-37.

- Zouboulis CC, Del Marmol V, Mrowietz U, Prens EP, Tzellos T, et al. (2015) Hidradenitis Suppurativa/Acne Inversa: Criteria for Diagnosis, Severity Assessment, Classification and Disease Evaluation. Dermatology 231:184-190.

- Smith MK, Nicholson CL, Parks-Miller A, Hamzavi IH (2017) Hidradenitis suppurativa: An update on connecting the tracts. F1000Research 6: 1272.

- Syed ZU, Hamzavi IH (2011) Atypical hidradenitis suppurativa involving the posterior neck and occiput. Arch Dermatol 147:1343-1344.

- Ring HC, Emtestam L (2016) The Microbiology of Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Dermatol Clin. 34: 29-35.

- Har-El G, Aroesty JH, Shaha A, Lucente FE (1994) Changing trends in deep neck abscess. A retrospective study of 110 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 77: 446-450.

- Sethi DS, Stanley RE (1994) Deep neck abscesses-Changing trends. J Laryngol Otol. 108: 138-143.

- Bottin R, Marioni G, Rinaldi R, Boninsegna M, Salvadori L, et al. (2003) Deep neck infection: a present-day complication. A retrospective review of 83 cases 1998-2001. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 260: 576–579.

- el-Sayed Y, al Dousary S (1996) Deep-neck space abscesses. J Otolaryngol 25: 227-233.

- Sakaguchi M, Sato S, Ishiyama T, Katsuno S, Taguchi K (1997) Characterization and management of deep neck infections. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 26: 131-134.

- Yamanaka T, Yamane K, Furukawa T, Matsumoto-Mashimo C, Sugimori C, et al. (2011) Comparison of the virulence of exopolysaccharide-producing Prevotella intermedia to exopolysaccharide non-producing periodontopathic organisms. BMC Infectious Diseases 11: 228.

- Kuriyama T, Nakagawa K, Karasawa T, Saiki Y, Yamamoto E, et al. (2000) Past administration of beta-lactam antibiotics and increase in the emergence of beta-lactamase-producing bacteria in patients with orofacial odontogenic infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 89: 186-192.

- McClay JE, Murray AD, Booth T (2003) Intravenous antibiotic therapy for deep neck abscesses defined by computed tomography. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 129: 1207-1212.

- Simo R, Hartley C, Rapado F, Zarod AP, Sanyal D, et al.(1998) Microbiology and antibiotic treatment of head and neck abscesses in children. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 23: 164-168.

- Gates GA (1983) Deep neck infection. Am J Otolaryngol. 4: 420-421.

- Chen MK, Wen YS, Chang CC, Lee H-S, Huang M-T, et al. (2000) Deep neck infections in diabetic patients. Am J Otolaryngol 21: 169-173.

- Yang SW, Lee MH, See LC, Huang SH, Chen TM, et al. (2008) Deep neck abscess: an analysis of microbial etiology and the effectiveness of antibiotics. Infect Drug Resist 1: 1-8.

Citation: Chounoune R, Kpodzo D, Udobi K, Sola R, Nguyen J, et al. (2019) Sepsis Due to Deep Posterior Neck Abscesses Secondary to Prevotella bivia: Beware of Emerging Opportunistic Pathogens. J Clin Stud Med Case Rep 6: 069.

Copyright: © 2019 Reginald Chounoune, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Journal Highlights

© 2024, Copyrights Herald Scholarly Open Access. All Rights Reserved!