A Study on Maternal Diet and Prospective Allergenic Solid Food Introduction among Chinese Infants Surveyed in a Private Hospital in Hong Kong

*Corresponding Author(s):

Chan JKCAllergy Centre, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong

Tel:+852 28358430,

Fax:+852 28987565

Email:June.kc.chan@hksh.com

Abstract

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

In the 1960’s solid food was usually started before 4 months of age but guidelines recommended delaying the introduction of solid food [4] and since 1990s recommended exclusive breast feeding until infants were at 6 months of age [5-7].

The Department of Health in Hong Kong (DHHK) recommends exclusive breastfeeding until around 6 months of age and then continuing breast milk until 2 years of age and beyond while introducing solid food and other milk alternatives [8]. The DHHK does not recommend eating any solid food before 4 months [9]. The latest breastfeeding survey shows that 27.9% of infants were breastfed without any infant formula supplementation; 27.0% had been started on complementary foods by 6 months of age, and 0.9% were exclusively breastfed according to the World Health Organization’s definition of exclusive breastfeeding [10,11].

Earlier guidelines had recommended avoidance of food allergens in high-risk infants to prevent food allergies but there is a lack of evidence to support this advice [12]. To the contrary, delayed allergenic food introduction may actually increase the risk of food allergy and eczema [2,13]. Recent research continues to support early introduction of allergenic foods to prevent allergy [3,14-18] and many guidelines have been updated [5,6,19,20].

However, many parents in Hong Kong still believe that they should delay the introduction of allergenic food and even health professionals often continue to provide such advice. There is very limited data on infant feeding practices to inform local strategies for early introduction of allergenic solid food. Therefore, we have conducted a survey in a group of Chinese parents attending a private hospital in Hong Kong on their maternal and child’s dietary intentions for the time of introduction of solid food and allergenic food. Differences in behavior between parents and children with different allergic histories have also been analyzed.

METHODS

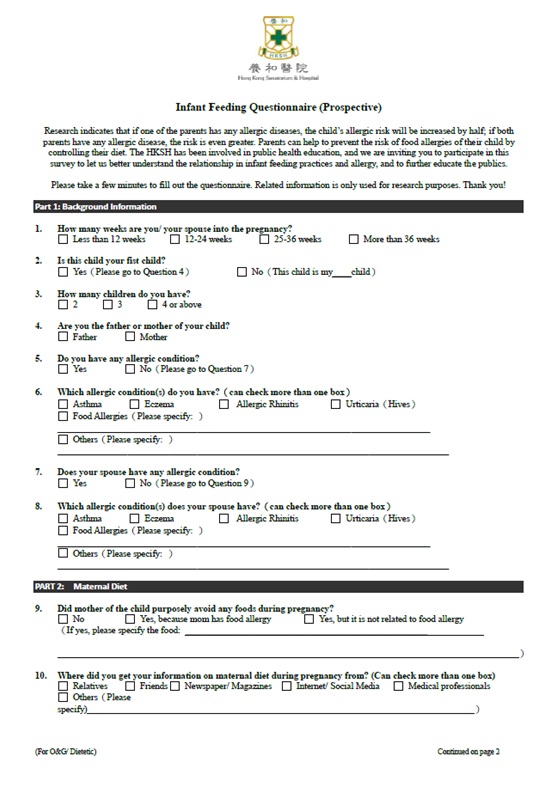

Figure 1A: Questionnaire.

Figure 1B: Questionnaire.

STATISTICS

ETHICS

RESULTS

Parents’ allergic history and maternal diet

Over half (55.1%) had instituted some non-allergy-related dietary restrictions during their current pregnancy, while 7.3% had avoided foods for various allergy-related reasons. In those who had avoided foods for allergy-related reasons, over half (57.1%) had stopped eating shellfish including shrimp, crab and scallops. In those who reported non-allergy-related dietary restrictions, avoidance of shellfish (38.2%), raw foods such as sashimi and salad (31.1%) and 'cold' foods as defined by Chinese culture such as herbal tea (16.5%) were frequently reported.

Subjects were asked about their sources of dietary information with multiple answers allowed. A majority of respondents had sought advice from relatives and friends for dietary information during pregnancy, 52.7% and 47.8% respectively; Internet /social media networks (45.9%) and newspaper/magazines/books (37.7%) were also common sources of maternal dietary information. On the other hand, only 26% had sought advice directly from healthcare professionals.

Infant feeding plans

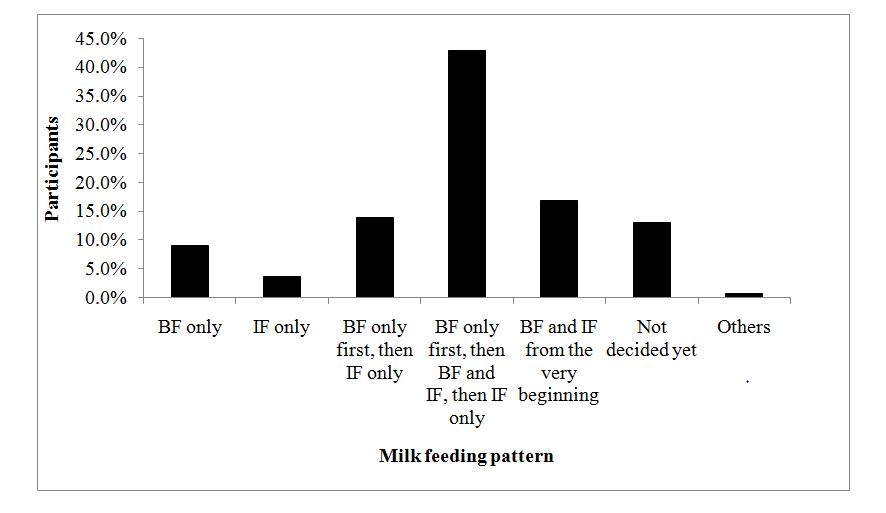

Figure 2: Planned infant milk feeding pattern.

Figure 2: Planned infant milk feeding pattern.BF=Breastfeeding; IF=Infant formula

Introduction of solid food and common food allergens

A majority of the parents planned to start introducing each of the common allergen after their baby was 6 months old (cumulative percentage 86.0-95.8%; Table 1). There was no significant difference between any of the 8 foods. Only 35.3% of the parents intended to introduce egg yolk after the child is 9 months old. Over half planned to introduce egg white, soy, wheat and fish after 9 months (51.2-61.2%). They intended to introduce shellfish and nuts even later, usually after the child is 12 months old.

|

Relative Percentage (%) |

|

Cumulative Percentage (%) |

||||||

|

|

0-3 Months |

3-6 Months |

6-9 Months |

9-12 Months |

12 Months onwards |

Number of responses |

After 6 Months* |

After 9 Months† |

|

Egg yolk |

1.1 |

12.9 |

50.7 |

21.0 |

14.3 |

272 |

86.0 |

35.3 |

|

Egg white |

1.5 |

10.2 |

35.3 |

24.8 |

28.2 |

266 |

88.4 |

53.0 |

|

Soy |

0.8 |

6.3 |

31.8 |

34.1 |

27.1 |

255 |

92.9 |

61.2 |

|

Wheat |

0.8 |

7.3 |

38.9 |

31.5 |

21.5 |

260 |

91.9 |

53.1 |

|

Shellfish |

0.9 |

3.3 |

11.7 |

18.7 |

65.4 |

214 |

95.8 |

84.1 |

|

Fish |

1.6 |

6.3 |

41.0 |

29.3 |

21.9 |

256 |

92.2 |

51.2 |

|

Nuts |

1.0 |

3.3 |

10.5 |

14.8 |

70.5 |

210 |

95.7 |

85.2 |

|

Milk |

4.4 |

6.4 |

35.3 |

25.3 |

28.5 |

249 |

89.2 |

53.8 |

*after 6 Months = total % of 6-9 Months, 9-12 Months and 12 Months onward.

†after 9 Months = total % of 9-12 Months and 12 Months onward.

Compared to those without allergic history, significantly fewer parents with allergic history planned to introduce all 8 allergenic foods before the child is 12 months old (11.6% vs. 5.2%, p=0.03) (Table 2). Overall, only 8.1% of parents are planned to introduce all 8 allergenic foods by 12 months. Moreover, parents with allergic diseases planned to introduce shellfish and egg white later in their infants as compared to those without a family history of allergic diseases, p for trend=0.02 and p=0.02, respectively (Table 3). There was no significant difference in time trend between the other 6 foods assessed.

|

Planned Time When All 8 Common Food Allergens Are Introduced (Age Of Child) |

|||||||||||

|

Parents allergic histories |

Total |

<= 12 Months |

> 12 Months |

Answered < 8 Foods |

No Answer/Not Planned At All |

95% Confidence Interval † |

P-Value* |

||||

|

n |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

||

|

All |

393 |

32 |

8.1 |

135 |

34.4 |

115 |

29.3 |

111 |

28.2 |

|

|

|

With Allergy |

191 |

10 |

5.2 |

65 |

34.0 |

64 |

33.5 |

52 |

27.2 |

2.54-9.42 |

0.03 |

|

Without Allergy |

190 |

22 |

11.6 |

67 |

35.3 |

49 |

25.8 |

52 |

27.4 |

7.4-17 |

|

|

Not indicated |

12 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

25.0 |

2 |

16.7 |

7 |

58.3 |

|

|

*P value comparing the % of babies introduced or planned to introduce all 8 allergenic foods by 12 months between parental allergic histories.

†95% Confidence Interval for % of babies introduced or planned to introduce all 8 allergenic foods by 12 months.

|

|

Parents |

0-3 Months |

3-6 Months |

6-9 Months |

9-12 Months |

> 12 Months |

No Answer /Not Planned |

P-Value* |

|||||

|

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|||

|

Egg yolk |

With Allergy |

1 |

0.8 |

13 |

9.8 |

68 |

51.1 |

33 |

24.8 |

18 |

13.5 |

58 |

0.15 |

|

Without Allergy |

2 |

1.5 |

21 |

15.7 |

68 |

50.8 |

22 |

16.4 |

21 |

15.7 |

56 |

||

|

Egg white |

With Allergy |

1 |

0.8 |

11 |

8.3 |

45 |

34.1 |

29 |

22.0 |

46 |

34.9 |

59 |

0.02 |

|

Without Allergy |

3 |

2.3 |

16 |

12.4 |

45 |

34.9 |

36 |

27.9 |

29 |

22.5 |

61 |

||

|

Soy |

With Allergy |

1 |

0.8 |

8 |

6.4 |

38 |

30.4 |

48 |

38.4 |

30 |

24.0 |

66 |

0.69 |

|

Without Allergy |

1 |

0.8 |

8 |

6.4 |

40 |

31.8 |

38 |

30.2 |

39 |

31.0 |

64 |

||

|

Wheat |

With Allergy |

1 |

0.8 |

9 |

7.2 |

50 |

40.0 |

40 |

32.0 |

25 |

20.0 |

66 |

0.65 |

|

Without Allergy |

1 |

0.8 |

10 |

7.7 |

49 |

37.7 |

40 |

30.8 |

30 |

23.1 |

60 |

||

|

Shellfish |

With Allergy |

1 |

1.0 |

4 |

3.9 |

7 |

6.9 |

13 |

12.8 |

77 |

75.5 |

89 |

0.02 |

|

Without Allergy |

1 |

0.9 |

3 |

2.8 |

17 |

15.7 |

27 |

25.0 |

60 |

55.6 |

82 |

||

|

Fish |

With Allergy |

3 |

2.4 |

7 |

5.5 |

56 |

44.1 |

36 |

28.4 |

25 |

19.7 |

64 |

0.86 |

|

Without Allergy |

1 |

0.8 |

9 |

7.3 |

46 |

37.1 |

38 |

30.7 |

30 |

24.2 |

66 |

||

|

Nuts |

With Allergy |

1 |

1.0 |

3 |

3.1 |

9 |

9.2 |

15 |

15.3 |

70 |

71.4 |

93 |

0.28 |

|

Without Allergy |

1 |

0.9 |

4 |

3.7 |

13 |

12.2 |

16 |

15.0 |

73 |

68.2 |

83 |

||

|

Milk |

With Allergy |

6 |

5.0 |

7 |

5.8 |

45 |

37.2 |

25 |

20.7 |

38 |

31.4 |

70 |

0.47 |

|

Without Allergy |

5 |

4.1 |

9 |

7.3 |

41 |

33.4 |

35 |

28.5 |

33 |

26.8 |

67 |

||

*p value comparing the % of babies introduced or planned to introduce all 8 allergenic foods by 12 months between parental allergic histories.

†95% Confidence Interval for % of babies introduced or planned to introduce all 8 allergenic foods by 12 months.

Concerns about solid introduction

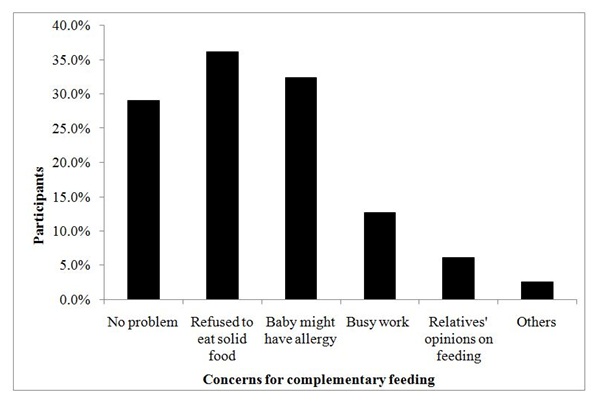

Figure 3: Percentage of parents with concerns for solid introduction.

DISCUSSION

The survey relied on convenience sampling which has advantages and disadvantages. While it gives valuable information in a timely manner for future larger scale study, this sampling method is bound for selection bias and sampling error. The Hong Kong’s health service is delivered through the public and private sectors. Private hospitals provide approximately 11% of hospital beds and treat 21% of the in-patients [22]. The current survey was conducted in the largest private hospital group in Hong Kong so will be skewed towards the segment of the community who can afford private healthcare and may not be representative of the whole local population [23]. However, high social economic status has been linked to increased risk of peanut allergy [24] as well as higher epinephrine auto-injector prescription [25]. Therefore, the findings are still informative not only because privately treated patients are a significant part of the community utilizing healthcare services in Hong Kong, but also because a similar study on the influence of allergic histories on parental feeding patterns for their babies in Hong Kong had not been conducted previously.

Maternal diet during pregnancy

Exclusive breastfeeding and formula feeding

Complementary feeding

Earlier guidelines had recommended delayed introduction of allergenic foods including dairy products, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts and fish [11]. However later studies have shown that delayed introduction of allergenic foods was correlated with increased risk of allergic diseases [3,14-18,33,34]. Furthermore, increased food diversity in the first year of life is inversely associated with allergic diseases [35]. Thus the early and diverse oral introduction of solid food may induce tolerance [36].

Newer guidelines recommend earlier allergen introduction during infancy [5,6,13,19,20]. The revised recommendations were supported by the Learning Early about Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study demonstrating that avoidance of peanut results in increased risk of developing peanut allergy in early childhood in high-risk infants [17]. As a result, the advice for introducing peanuts during infancy has been modified [5,37,38]. The Enquiring about Tolerance (EAT) study demonstrated the importance of early introduction of common allergens, especially egg and peanut, in food allergy prevention for the general population [18].

Focusing on the Asian population, the LEAP study showed that there was no peanut allergy in the peanut consumption group versus a 44.4% incidence in the peanut avoidance group, suggesting that early introduction is even more effective for preventing food allergy in the Asian population [17]. The Asia Pacific Association of Pediatric Allergy, Respirology & Immunology (APAPARI) has already recommended that there should be no delay in introducing allergenic foods in high-risk infants [26].

Most Chinese infants were fed with solids after 6 months old and about one third had started complementary feeding at 4 to 6 months old [38]. This survey has shown that parents often planned to introduce solid food and allergens after the infant are 6 months old and some after 9 months of age. Some parents in the high-risk population reported planning to introduce solids after 12 months. Significantly fewer families with a history of allergic diseases planned to introduce all allergenic foods by 12 months.

A significant percentage of parents reported a fear of their child getting food allergy. They were also afraid that their child would refuse solids. In addition, how and when a child is introduced to solid food can be affected by a family history of allergic diseases. A previous study from the United States also indicated that maternal allergic history and the Asian race are risk factors for late solid introduction [39]. These findings highlight the importance of seeking professional advice early so that appropriate support and guidance can be offered.

As a result of this survey, we now provide advice in our routine maternity classes about maternal diet for allergy prevention in the offspring. We have also launched a program for the early introduction of solids to educate and provide guidance for parents of high risk infants. The Eating Allergen Safely & Early (EASE) Program was designed and launched by a multi professional team that included dietitians and nurses specializing in allergy and consultant allergists [40]. The program consists of consultations with an allergist and skin prick testing to common food allergens to rule out existing allergies, followed by monthly dietetic consultations and nursing advice in the first year to guide parents in the introduction of various solids including commonly allergenic foods. Parents are taught to observe signs of readiness for solid food introduction in their infants and to start with rice cereals as the first food beginning at 4 to 6 months while continuing to breastfeed. They are also encouraged to try different grains, vegetables and fruits. After the infants are eating solid food on a daily basis, parents are guided to introduce the common allergenic foods, including milk, fish, shellfish, soy, egg and peanut. The infants are expected to consume these foods on a regular basis by 12 months of age. Early symptoms of food allergy are referred to an allergist and treated in a timely fashion. Parents are educated on nursing care related to their baby’s eczema or other allergic symptoms as needed. Food allergy status is reviewed at 1 and 3 years old, or as medically needed.

The introduction of any local policy to change infant feeding patterns to prevent allergic diseases in Hong Kong will require a major shift in societal culture. Before this public health policy can be recommended more evidence is required. We propose that a community wide survey in Hong Kong should be conducted to document whether our findings are applicable to the wider community and whether the delayed feeding of allergenic foods predisposes to an increased risk for allergic diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

REFERENCES

- Ho MH, Lee SL, Wong WH, Ip P, Lau YL (2012) Prevalence of self-reported food allergy in Hong Kong children and teens--a population survey. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 30: 275-284.

- Du Toit G, Katz Y, Sasieni P, Mesher D, Maleki S, et al. (2008) Early consumption of peanuts in infancy is associated with a low prevalence of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 122: 984-991.

- Ierodiakonou D, Garcia-Larsen V, Logan A, Groome A, Cunha S, et al. (2016) Timing of allergenic food introduction to the infant diet and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 316: 1181-1192.

- Koplin JJ, Allen KJ (2013) introduction-why are the guidelines always changing? Clin Exp Allergy 43: 826-834.

- Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA) (2016) Infant feeding and allergy prevention. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA), Balgowlah, Australia.

- Fewtrell M, Bronsky J, Campoy C, Domellöf M, Embleton N, et al. (2017) Complementary feeding: A position paper by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 64: 119-132.

- Muraro A, Halken S, Arshad SH, Beyer K, Dubois AE, et al. (2014) EAACI food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines. Primary prevention of food allergy. Allergy 69: 590-601.

- Family Health Service (FHS) (2014) The Essentials of Infant & Young Child Feeding. Family Health Service (FHS), Hong Kong.

- Family Health Service (FHS) (2017) Healthy Eating for 6 to 24 month old children (1) Getting Started. Family Health Service (FHS), Hong Kong.

- Family Health Service (2017) Breastfeeding Survey 2017. Family Health Service, Hong Kong.

- World Health Organization (WHO) Exclusive breastfeeding for optimal growth, development and health of infants. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Kleinman RE (2000) Complementary feeding and later health. Pediatrics 106: 1287.

- Agostoni C, Decsi T, Fewtrell M, Goulet O, Kolacek S, et al. (2008) Complementary feeding: A commentary by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 46: 99-110.

- Alm B, Aberg N, Erdes L, Möllborg P, Pettersson R, et al. (2009) Early introduction of fish decreases the risk of eczema in infants. Arch Dis Child 94: 11-15.

- Nwaru BI, Takkinen HM, Niemela O, Kaila M, Erkkola M, et al. (2013) Timing of infant feeding in relation to childhood asthma and allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 131: 78-86.

- Koplin JJ, Osborne NJ, Wake M, Martin PE, Gurrin LC, et al. (2010) Can early introduction of egg prevent egg allergy in infants? A population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 126: 807-813.

- Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, Bahnson H, Radulovic S, et al. (2015) Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med 372: 803-813.

- Perkin MR, Logan K, Marrs T, Radulovic S, Craven J, et al. (2016) Enquiring About Tolerance (EAT) study: Feasibility of an early allergenic food introduction regimen. J Allergy Clin Immunol 137: 1477-1486.

- Schafer T, Bauer P, Beyer K, Bufe A, Friedrichs F, et al (2014) S3-Guideline on allergy prevention: 2014 update: Guideline of the German Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI) and the German Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine (DGKJ). Allergo J Int 23: 186-199.

- Fleischer DM, Spergel JM, Assa’ad AH, Pongracic JA (2013) Primary prevention of allergic disease through nutritional interventions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 1: 29-36.

- Yang Z, Zheng W, Yung E, Zhong N, Wong GW, et al. (2015) Frequency of food group consumption and risk of allergic disease and sensitization in schoolchildren in urban and rural China. Clin Exp Allergy 45: 1823-1832.

- Kong X, Yang Y, Gao J, Guan J, Liu Y, et al. (2015) Overview of the health care system in Hong Kong and its referential significance to mainland China. J Chin Med Assoc 78: 569-573.

- Tripepi G, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, Zoccali C (2010) Selection bias and information bias in clinical research. Nephron Clin Pract 115: 94-99.

- American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (2012) Socioeconomic Status Linked To Childhood Peanut Allergy. American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, Illinois, USA.

- Coombs R, Simons E, Foty RG, Stieb DM, Dell SD (2011) Socioeconomic factors and epinephrine prescription in children with peanut allergy. Paediatr Child Health 16: 341-344.

- Tham EH, Shek LP, Van Bever HP, Vichyanond P, Ebisawa M, et al. (2018) Early introduction of allergenic foods for the prevention of food allergy from an Asian perspective-An Asia Pacific Association of Pediatric Allergy, Respirology & Immunology (APAPARI) consensus statement. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 29: 18-27.

- Chan AW, Chan JK, Tam AY, Leung TF, Lee TH (2016) Guidelines for allergy prevention in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 22: 279-285.

- Garcia-Larsen V, Ierodiakonou D, Jarrold K, Cunha S, Chivinge J, et al. (2018) Diet during pregnancy and infancy and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 15: 1002507.

- Lau Y (2012) Traditional Chinese pregnancy restrictions, health-related quality of life and perceived stress among pregnant women in Macao, China. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 6: 27-34.

- Liu X, Lu J, Wang H (2017) When health information meets social media: Exploring virality on sina weibo. Health Commun 32: 1252-1260.

- Family Health Service (2017) Breastfeeding Policy of the Department of Health. Family Health Service, Hong Kong.

- Reilly JJ, Wells JC (2005) Duration of exclusive breast-feeding: Introduction of complementary feeding may be necessary before 6 months of age. Br J Nutr 94: 869-872.

- de Silva D, Geromi M, Halken S, Host A, Panesar S, et al. (2014) Primary prevention of food allergy in children and adults: Systematic review. Allergy 69: 581-589.

- Zutavern A, Brockow I, Schaaf B, von Berg A, Diez U, et al. (2008) Timing of solid food introduction in relation to eczema, asthma, allergic rhinitis, and food and inhalant sensitization at the age of 6 years: Results from the prospective birth cohort study LISA. Pediatrics 121: 44-52.

- Roduit C, Frei R, Depner M, Schaub B, Loss G, et al. (2014) Increased food diversity in the first year of life is inversely associated with allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 133: 1056-1064.

- Lack G (2012) Update on risk factors for food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 129: 1187-1197.

- Fleischer DM, Sicherer S, Greenhawt M, Campbell D, Chan E, et al. (2015) Consensus communication on early peanut introduction and the prevention of peanut allergy in high-risk infants. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 11: 23.

- He YN, Zhai F (2001) Complementary feeding practice in Chinese rural children. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 30: 305-307.

- McKean M, Caughey A, Leong R, Wong A, Cabana M (2015) The timing of infant food introduction in families with a history of atopy. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 54: 745-751.

- Lee WL, Chan J, Chi S, Lee L, Lau PC, et al. (2018) The journey to create the new allergy centre in Hong Kong. J Pract Proff Nurs 2: 005.

Citation: Chan JKC, Lee TH, Chan WM, Chow WS, Luk WP, et al. (2018) A Study on Maternal Diet and Prospective Allergenic Solid Food Introduction among Chinese Infants Surveyed in a Private Hospital in Hong Kong. J Pract Prof Nurs 2: 008.

Copyright: © 2018 Chan JKC, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.