ABSTRACT

Clozapine Induced Myocarditis (CIM) is a relatively rare but potentially fatal side effect of clozapine. This side-effect is difficult to anticipate, diagnose, and treat because of an ambiguous susceptibility profile and presentation. Considering the importance of clozapine in the management of psychiatric disorders, it is important to pay attention to side-effects that can limit the enthusiasm of both physicians and patients to use clozapine. This is a case of CIM in a 21-year-old African American male who was managed for treatment resistant schizophrenia. This case report outlines the course of the disease and highlights the parameters that were useful in our diagnosis and management. Our goal is to increase awareness of CIM and contribute to the ongoing efforts to create algorithms for predicting and recognizing CIM.

Keywords

Antipsychotic; Clozapine; Clozapine Induced Myocarditis (CIM); Eosinophilia; Fever; Inflammation; Myocarditis; Schizophrenia; Side effect; Tachycardia

Introduction

Compared to other antipsychotics, clozapine has been found to substantially reduce suicide rates, inpatient admissions, extrapyramidal symptoms, and negative symptoms among schizophrenic patients [1]. It is usually reserved for treatment refractory or treatment resistant schizophrenia, where treatment-resistant refers to the trial of two or more medications [1]. In addition, clozapine is beneficial in the management of treatment-resistant mania, severe psychotic depression, idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease [2]. Despite its many indications, clozapine is grossly underutilized due to the significant side effect profile. The more frequent side effects of clozapine include tachycardia, fever, sedation, lower seizure threshold, increased appetite, constipation, nausea, polyphagia, sialorrhea, and weight gain. The less common but more debilitating side effects include agranulocytosis, periodic cataplexy, anemia, and myocarditis [3]. Of the major side effects, agranulocytosis has received the most attention because of the risk of mortality, relatively high incidence, and associated mandatory monitoring requirements [3]. Although, not as notorious, CIM has an incidence of about 0.5-3% [4-6]. It has been reported more often in males and it has a median age of occurrence of 30 years with an age range of 16 to 77 years in reported cases [5]. It occurs rapidly, often within 14-21 days of initiating clozapine, has a fatality rate between 10% to 64%, and can be easily missed [1,4]. Also, monitoring and diagnosis of this condition is difficult because of the undefined symptoms, signs, and course of the disease. We present a case of CIM including a timeline of events to increase the awareness of this condition and enhance efforts to create a standard diagnostic algorithm.

Case Presentation

We present a 21-year-old African American male with a history of early onset schizophrenia, diagnosed at age 13 years, who presented to the emergency department with auditory hallucinations, mutism, and catatonia. Patient has had multiple hospitalizations in the past for psychosis and has previously been managed with olanzapine.

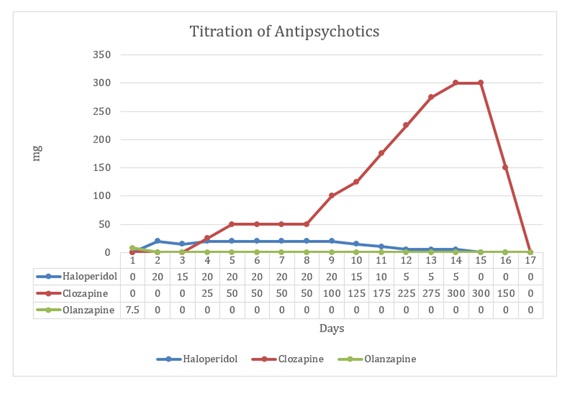

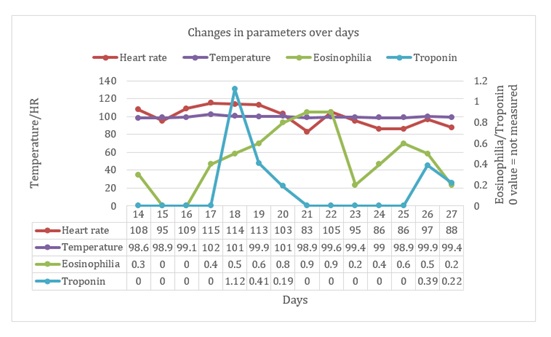

On admission, patient was started on haloperidol 10 mg per oral (PO) twice daily; lorazepam 1 mg PO in the morning and 2 mg PO at bedtime; and lithium 300 mg PO twice daily. By admission day 3, his symptoms became worse including poor self-care, avolition, apathy, waxy flexibility, posturing, automatic obedience, and ambitendency. Subsequently, patient was started on clozapine at 25mg PO daily and haloperidol was gradually tapered and eventually discontinued on day 14. Clozapine was gradually titrated up to 150 mg PO twice daily by admission day 14. On admission day 17, patient developed persistent tachycardia (heart rate:115 bpm), fever (102.4ºF), eosinophilia, and mild leukocytosis (11,200 cells/ml) with automated neutrophil count of 7600. (Figure 1)

Immediately, clozapine was discontinued, and patient was transferred to the telemetry unit. On day 18, troponin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and D-dimer were elevated. Repeat electrocardiogram (EKG) compared to baseline EKG revealed sinus tachycardia (ventricular rate: 105 bpm) (Figure 2). Echocardiogram on the same day revealed mild left ventricular systolic dysfunction with apex hypokinesis, ejection fraction (EF): 45%. CT scan of the chest showed small right and trace left pleural effusions with bibasilar infiltrates and atelectasis. Subsequently, CT scans of the head and abdomen, cardiac catheterization, lower extremities venous duplex scan, ventilation-perfusion (VQ) scan, and blood cultures returned without findings.

From day 17 to day 28, patient was managed with vancomycin, meropenem, acyclovir, and supportive care. Repeat echocardiogram on day 24 showed normal left ventricular systolic function with mild apex hypokinesis, EF: 65%. By day 28, all cardiac symptoms were resolved.

Discussion

CIM is a clozapine induced inflammatory disorder of the cardiac muscle. Myocarditis, in general, can occur due to both infectious and non-infectious causes. Non-infectious causes can be immune-mediated or due to toxicity. Immune-mediated myocarditis can be triggered by allergens, alloantigens, and autoantigens while toxic causes are from drugs, heavy metals, hormones, physical agents like radiation and biologic agents like snake venom. The resulting inflammation can present with a variety of symptoms including fatigue, fever, chest pain, arrhythmias, cardiogenic shock and sudden death. The diagnosis of myocarditis is confirmed through pathologic examination of biopsied endomyocardial tissue. Due to the invasive nature of this test, myocarditis is difficult to diagnose and treat. Management is achieved by treating the underlying cause, if known, and supportive care of presenting symptoms [7].

In a significant majority of cases (about 75-90%), CIM develops within the first 12 weeks of initiating treatment [8]. Probable risk factors include a high dose at initiation of clozapine, rapid rate of titration of clozapine, drug interactions (valproate, lithium, and SSRIs have been mentioned), and older age [9]. In addition to these, general risk factors for myocarditis include obesity, alcohol use, selenium deficiency, smoking, and a poor premorbid cardiac condition [9]. Unfortunately, most psychiatric patients are also exposed to the general risk factors due to the prevalence of metabolic comorbidities and substance use among this population [10]. Of the many theories that have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of CIM; an IgE driven autoimmune-mediated inflammatory process is the most mentioned [11]. Others include intrinsic clozapine facilitated actions like increasing circulating catecholamine levels and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [11].

CIM is difficult to diagnose because of an ill-defined susceptibility profile and its non-specific and inconsistent presentation [5]. Furthermore, the signs that are most apparent and suggestive of CIM like eosinophilia, fever, and tachycardia can occur in patients initiating clozapine who will not eventually develop myocarditis [5], or perhaps, clinically overt myocarditis since it is difficult to ascertain the absence of an inflammatory process without a biopsy. Moreover, these signs, occurring severally or together, can be caused by a broad array of conditions. Also, several cases of asymptomatic CIM have been reported [5,9]. The consensus concerning the diagnosis of CIM is “a high index of suspicion” [4,5,9]. Notwithstanding, close monitoring of several parameters has been proposed but the parameters that are most predictive are unclear. The most detailed monitoring protocol was proposed by Ronaldson et al and it recommends a baseline echocardiogram, assays of troponin I/T and CRP, and monitoring troponin and CRP on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 [12]. This protocol has significant cost implications which may further discourage the use of clozapine [9]. Once discovered, CIM has been effectively treated in most cases by stopping Clozapine and initiating supportive care with other medications as needed; some patients have even been successfully re-challenged with clozapine [5,9,13]. Nonetheless, CIM is a potentially lethal adverse effect of clozapine therapy with reported mortality rates, as previously mentioned, ranging from 10 to 64% [1,14]. Long term sequela of CIM, if any, have not been reported, although clozapine is known to cause insidious cardiomyopathies which occur after months of treatment [4,5]. It is uncertain if patients who develop CIM will develop some form of cardiomyopathy consequently.

Our patient’s presentation, including results of chest CT scan, echocardiogram, and serology is consistent with previous findings in cases of CIM [7,11]. The factors that may have been protective for him include his young age, lack of co-morbid conditions, no history of substance use, low dose at initiation of clozapine, and titration of clozapine at the recommended rate [15]. Possible adverse factors include obesity (BMI- 32.5kg/m²) and, the coadministration of Lithium. He had a baseline EKG before the initiation of clozapine which was normal, but he did not have a baseline echocardiogram and troponin/CRP assay as some of the monitoring protocols have suggested [12]. In diagnosing this patient, the upward trending of eosinophilia and concomitant fever were most useful in sparking our suspicion while the elevated CRP and troponin were highly corroborative. We believe that the early involvement of the cardiology team and withdrawal of clozapine were very helpful in the management. Our patient was not re-challenged, and he has not developed any sequela to CIM.

Clozapine associated myocarditis has been reported for decades but remains understudied and underreported [4,5]. While it is difficult to create screening tests and algorithms for relatively low incidence and serious diseases, the underreporting of this condition makes the task even more difficult. Considering the importance of clozapine to the management of schizophrenia and the severity of CIM, this side effect needs to be reported at every opportunity. From our experience, we recommend- as many before have- a high index of suspicion, immediate institution of multi-specialty management in new patients on clozapine who develop fever, eosinophilia, and tachycardia, and a very low threshold for ordering troponin, CRP, and an echocardiogram in symptomatic patients.

Consent

The patient's consent was obtained orally.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors Contributions

All authors have participated in the procurement of this document and agree with the submitted case report.

Acknowledgments

No further acknowledgements.