Provider Spirituality and Holistic Healthcare Approaches in Naturopathic Medical Students

*Corresponding Author(s):

James E McDonaldBastyr University, 14500 Juanita Drive NE, Kenmore, 98028, Washington, United States

Tel:+1 4253816066,

Email:james.mcdonald@bastyr.edu

Abstract

This pilot study gathered data about naturopathic medical students’ experience of connection with the transcendent in daily life and the ways in which they anticipate incorporating spirituality in their future practice.

Subjects

Naturopathic physicians in training (n=32).

Design

Anonymous, self-report survey with both correlational and descriptive components.

Outcome Measures

Participants completed two surveys designed to measure provider spirituality, the likelihood of a provider asking about a patient’s spiritual health, the importance of spirituality in patient interventions, and the anticipated methods for assessing and supporting patient spiritual growth.

Results

Results showed a positive correlation between provider spirituality and the importance naturopathic doctors in training place on incorporating spirituality in patient interventions. The responses to open-ended questions revealed that naturopathic medical students plan to support future patients in their spiritual growth by cultivating their mind-body connection. Finally, students plan to infer a patient’s relationship with their spirituality indirectly, rather than with direct assessment.

Conclusion

Results suggest that while naturopathic medical students’ report that incorporating spirituality in patient interventions is important; there may be barriers to assessing and addressing spirituality within holistic primary care.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Despite the connection between spirituality and health, many primary care practitioners report that they support patients’ spiritual well-being in principle, yet receive little training in the area of addressing a patient’s spirituality [10]. Sullivan, Lakoma and Block found that nearly 50% of medical students felt unprepared to address spiritual issues in end-of-life care [10]. Currently, there is no universal training curriculum on spirituality and health in medical schools in the United States (US), yet many patients desire to discuss matters of spirituality with their primary care practitioner, especially when facing a serious disease and the possibility of death [10-12].

In contrast to the training of allopathic physicians, naturopathic physicians are trained to take a holistic view of the patient, to consider what the potential barriers may be to optimal health and to stimulate the inherent self-healing process within each individual [13]. This paradigm of whole person healthcare incorporates the spiritual and appears to be an essential element in Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) [14]. Some of the literature in the area of spirituality in primary care practice focuses on provider opinions about incorporating CAM. For example, Curlin found that only those practitioners who rated themselves as “very spiritual” integrate CAM in their practice [15]. In addition, acupuncturists and naturopaths scored higher on measures of religiosity and spirituality than did general internists and rheumatologists [15].

Aims of the pilot study

• What methods might naturopathic medical students use in their future practice to support patients’ spiritual growth?

• How might naturopathic medical students assess a patient’s relationship with their spirituality?

• Does the daily spiritual experience of naturopathic medical studentspositively correlate with the extent to which they feel it is important to incorporate spirituality in patient interventions?

• Does the daily spiritual experience of naturopathic medical students positively correlate with how likely they are to ask a patient about their spiritual health?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Study design

Measures

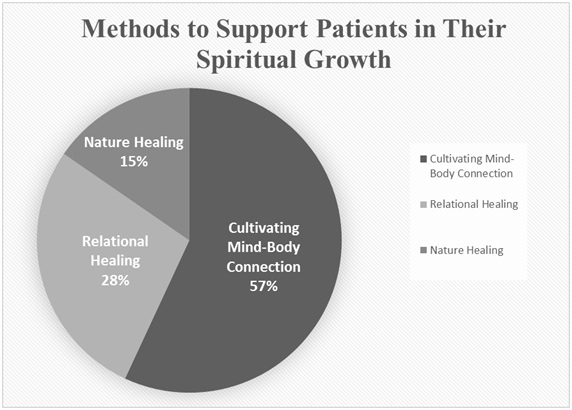

Participant responses to the open-ended questions asking them to describe the methods they would use to support patient’s spiritual growth were classified into three general categories: (1) cultivating the mind-body connection, (2) relational healing and (3) nature healing. A rating sheet was developed with definitions outlining the different categories and a short training provided for two raters who were asked to assign a category to each. For the categorization of the responses for the open-ended question asking about methods naturopathic doctors in training may use to support patients in their spiritual growth, interrater reliability was high at 95%. For the second open-ended question examining ways in which future naturopathic physicians would assess a patient’s relationship with their spirituality, researchers coded responses into one of three categories: (1) ask the patient directly, (2) infer through other information the patient provides and (3) other. For this open-ended question, interrater reliability was also high, at 99%. After receiving University Institutional Review Board approval for the study, surveys were distributed to all students in the naturopathic medicine program of study.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

Scores on the first single-item question, “How likely are you to ask about a patient’s spirituality?” returned a mean of 4.5±0.76, indicating that naturopathic medical students are between somewhat likely and very likely to ask about a patient’s spirituality. The second single-item question, “How important is it to incorporate spirituality in patient interventions?” had a mean of 4.32±0.77, indicating that most respondents felt it was very important to somewhat important. As with the DSES, the series mean was calculated for a single missing data point for this question [19].

A total of 65 responses describing methods to support patients in their spiritual growth were reported and coded by raters into three methods of encouraging spiritual growth: cultivating the mind-body connection, relational healing and nature healing. As can be seen in figure 1, cultivating the mind-body connection was the most frequently reported method for supporting patients in their spiritual growth.

Responses were numerous and varied greatly, some examples of responses for each of the categories is outlined in the table 1 below.

The 39 responses to the second open-ended question, “how would you assess a patient’s relationship with their spirituality”, were evenly split between directly asking, (43%) and inferring from other information (49%). Some methods of assessment included: Deep listening, discovering and using language to describe the transcendent that is preferred by the patient, using spirituality surveys, and asking about patient’s relationships with others.

|

Cultivating Mind-Body Connection |

Relational Healing |

Nature Healing |

|

Bodywork |

Talking with patients |

Plant-spirit healing |

|

Craniosacral therapy |

Encouraging them |

Connecting to nature |

|

Mindfulness/Meditation/ Prayer |

|

Offering retreats |

|

Yoga |

|

Hiking in the woods |

Hypothesis testing

DISCUSSION

Limitations

Future research directions

CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

REFERENCES

- McCullough ME, Willoughby BL (2009) Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: Associations, explanations, and implications. Psychol Bull 135: 69-93.

- Chida Y, Steptoe A, Powell LH (2009) Religiosity/spirituality and mortality. A systematic quantitative review. Psychother Psychosom 78: 81-90.

- Lawler KA, Younger JW (2002) Theobiology: An analysis of spirituality, cardiovascular responses, stress, mood, and physical health. J Relig Health 41: 347-362.

- Edmondson D, Park CL, Chaudoir SR, Wortmann JH (2008) Death without God: Religious struggle, death concerns, and depression in the terminally ill. Psychol Sci 19: 754-758.

- Gillum F, Williams C (2009) Associations between breast cancer risk factors and religiousness in American women in a national health survey. J Relig Health 48: 178-188.

- Visser A, Garssen B, Vingerhoets A (2010) Spirituality and well-being in cancer patients: A review. Psychooncology 19: 565-572.

- Farias M, Underwood R, Claridge G (2013) Unusual but sound minds: Mental health indicators in spiritual individuals. Br J Psychol 104: 364-381.

- Bryant-Davis T, Wong EC (2013) Faith to move mountains: Religious coping, spirituality, and interpersonal trauma recovery. Am Psychol 68: 675-684.

- Jankowski PJ, Vaughn M (2009) Differentiation of self and spirituality: Empirical explorations. Couns Values 53: 82-96.

- Sullivan AM, Lakoma MD, Block SD (2003) The Status of Medical Education in End-of-life Care. J Gen Intern Med 18: 685-695.

- MacLean CD, Susi B, Phifer N, Schultz L, Bynum D, et al. (2003) Patient preference for physician discussion and practice of spirituality: Results from a multicenter patient survey. J Gen Intern Med 18: 38-43.

- Vi AHF, Barnett KG (2004) Medical school curricula in spirituality and medicine. JAMA 291: 2883-2883.

- American Association of Naturopathic Physicians (2011) Definition of Naturopathic Medicine. American Association of Naturopathic Physicians, Washington, DC, USA.

- Chez RA, Jonas WB, Crawford C (2011) A survey of medical students’ opinions about complementary and alternative medicine. Am J Obstet Gynecol 185: 754-757.

- Curlin FA, Rasinski KA, Kaptchuk TJ, Emanuel EJ, Miller FG, et al. (2009) Religion, clinicians, and the integration of complementary and alternative medicines. J Alter Complementary Med 15: 987-994.

- Underwood LG (2006) Ordinary spiritual experience: Qualitative research, interpretive guidelines, and population distribution for the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale. Arch Psychol Relig 28: 181-218.

- Underwood LG (2011) The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Overview and results. Religions 2: 29-50.

- Underwood LG, Teresi JA (2002) The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Ann Behav Med 24: 22-33.

- Velicer WF, Colby SM (2005) A comparison of missing-data procedures for arima time-series analysis. Educ and Psychol Meas 65: 596-615.

Citation: McDonald JE, Lester N (2019) Provider Spirituality and Holistic Healthcare Approaches in Naturopathic Medical Students. J Altern Complement Integr Med 5: 071.

Copyright: © 2019 James E McDonald, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.