Understanding of Care Coordination by Healthcare Providers and Staff at Federally Qualified Health Centers: A Qualitative Analysis

*Corresponding Author(s):

Hong Z ChartrandArea Health Education Center Program, Kirksville College Of Osteopathic Medicine, AT Still University, Missouri, United States

Tel:+1 6606262247,

Email:hongchartrand@atsu.edu

Abstract

Background

Care coordination in Patient-Centered or Family-Centered Medical Home (PCMH/FCMH) models is one evidence-based strategy to better manage childhood chronic diseases. Although many Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) incorporate PCMH/FCMH care coordination models, few studies have investigated FQHC personnel understanding of care coordination, and the effect of FQHC location (rural versus urban) on care coordination for childhood diseases has not been well documented.

Objective

To investigate FQHC personnel understanding of care coordination for pediatric patients.

Subject

Thirty providers and staff from 1 urban and 1 rural FQHCs.

Measures

Interviews and reports were analyzed using content analysis to determine participants understanding of care coordination facilitators and barriers for pediatric patients.

Results

Seven categories of facilitators were identified: teamwork, integrated services, one-stop shop, dedicated referral coordinator, effective and open communication, technology, and culture. There were 3 levels of barriers to care coordination: individual, organizational, and systems. Many facilitators and barriers were universal to both urban and rural FQHCs, but some were distinct for only the urban or rural FQHC. For example, lack of pediatric specialty care happened more often in the rural FQHC.

Conclusion

FQHC personnel consider teamwork with all stakeholders and integration of services to be facilitators of care coordination. Urban and rural FQHCs had similar barriers to care coordination. To improve outcomes associated with care coordination, a solid working definition of care coordination is necessary, and reimbursing care coordination activities should be explored by FQHCs, other healthcare systems and healthcare policy.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

In the past few decades, the number of children with chronic diseases has increased rapidly in the United States [1], and around 27% of children have at least one chronic health condition requiring continual medical attention and contributing to missing school and their parents missing work [2]. Many of these chronic diseases are costly but preventable or manageable. Multiple barriers, such as insufficient patient education, fragmented care, stress, health beliefs and cultural beliefs, environmental effects and financial burden, hinder quality of pediatric care [3-8], and children in low-income or minority families are especially vulnerable [9]. People, including children with complex chronic conditions can use more health and social services than the rest of the population [10]. Care coordination is an evidence-based strategy for addressing barriers and improving care [11,12].

Care coordination in Patient-Centered or Family-Centered Medical Homes (PCMH/FCMH) can be used to manage diseases. Patients receive multiple services in one location, and healthcare teams coordinate care throughout the healthcare system, social services, and the community [13,14]. However, providers have different definitions about care coordination, and more than 40 have been identified [15,16]. Thus, consensus on care coordination is lacking and necessary [17].

Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHCs) is local, nonprofit, community-based healthcare clinics serving low-income and medically underserved communities. They provide primary and preventive care across a range of health and social services [15,18]. Many FQHCs have established or are working to establish PCMH/FCMHs and implemented care coordination [19], but successful care coordination is affected by multiple factors. Further, rural FQHCs generally have fewer resources than urban FQHCs [20].

Few studies have investigated understanding of care coordination by FQHC personnel. One study [21] suggested care coordination should be investigated in urban and rural FQHCs, but little research exists for urban versus rural location on care coordination, especially for children. The purpose of this study was to investigate FQHC personnel understanding of care coordination for pediatric patients, particularly those with complex chronic diseases. Specifically, we evaluated care coordination facilitators and barriers in an urban and a rural FQHC.

MATERIALS

Study framework

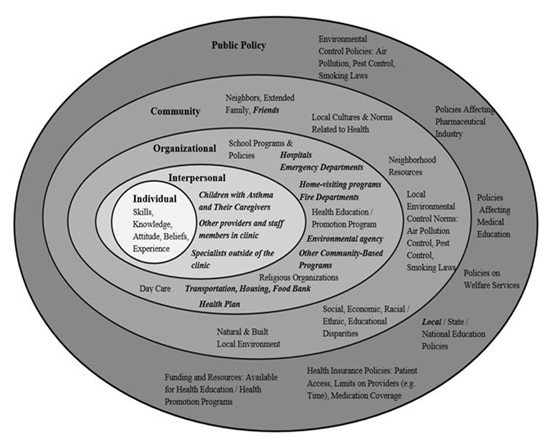

Figure 1: Example of an ecological model for treating childhood asthma [22].

Note: The model illustrates the needs and opportunities for collaboration between healthcare providers, families, and communities. Modified components of the model that apply to the current study are in italics. Application of the ecological model to childhood disease management at FQHCs in urban and rural settings can highlight care coordination activities at FQHCs to manage childhood chronic diseases, connect children with chronic diseases to internal and external resources and potentially improve the management of childhood disease conditions.

Study approach

Study locations

Participants

Study protocol

Data analysis

RESULTS

Facilitators of care coordination

|

Urban FQHC |

Rural FQHC |

||||

|

Number |

|

Title |

Number |

|

Title |

|

4 |

|

Physician* |

2 |

|

Physician*** |

|

2 |

|

Nurse |

3 |

|

Nurse**** |

|

2 |

|

Behavioral Health Consultant |

2 |

|

Behavioral Health Consultant |

|

2 |

|

Registered Dietician |

|

|

Registered Dietician***** |

|

1 |

|

Care Coordinator |

2 |

|

Referral Coordinator/Care Coordinator****** |

|

2 |

|

Medical Assistant |

2 |

|

Medical Assistant |

|

2 |

|

Referral Coordinator |

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

Pharmacist** |

2 |

|

Pharmacist |

|

* This includes Chief Medical Officer (CMO), who is also a practicing physician, and Pediatric Head. ** We did not interview any pharmacist at one clinic site because we were told that they did not have a pharmacist in its pediatric department. At another clinic site, two pharmacists came to interview together and one of these was the Pharmacy Manager. |

*** The Chief Medical Officer (CMO) is an OB/GYN. Therefore, the Medical Director was selected for the interview concerning the overall effort of care coordination. He was counted under the category of physician. ***** The rural FQHC did not have a registered dietician on the care team during the interview time. |

||||

|

Facilitator |

|

Urban |

Rural |

|

Teamwork |

|

√ |

√ |

|

Integrated services |

|

√ |

√ |

|

One-stop shop |

|

√ |

√ |

|

Dedicated referral coordinator |

|

|

√ |

|

Effective and open communication |

|

√ |

√ |

|

Technology (ECW, EHR) |

|

√ |

√ |

|

Culture |

|

√ |

|

For parents, integrated services were convenient and saved time. One parent said, “Having a dentist come into the room is so great. It would have taken me a lot longer to bring my son to the dentist if it weren’t for the integrated dental program”. For the FQHCs, integrated services helped retain patients and keep them on track. One participant said, “Having services here, we increase how much people follow up. So I think that having as many services as we can here help to keep [patients] at least that much healthier. It is called a one-stop shop. I think that makes a huge difference, especially since people are busy, when people are stretching for finance or when they have to bring all of their children in for the appointment”.

Barriers to care coordination

|

Level |

|

Barriers |

|

Urban |

|

Rural |

|

Patient |

|

Hard to reach patients because of address and phone number changes |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

Difficult to communicate with patients and families because of limited health literacy and English proficiency |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

Lack of patient compliance because of financial difficulty or insurance issue |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

Patient fear because of immigration status in the United States |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

Lack of transportation for appointments |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

Lack of time for appointments |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

Parent(s) and the entire family lack education, awareness, and influence |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

Patient’s belief system |

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

Provider |

|

Belief system about medication |

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

Lack of time to see patients because of high volume of patients and reimbursement model |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

Lack of knowledge about where to refer the patient to community resources |

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

Lack of communication between primary care provider and specialist |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

Barriers from specialists who ask parents to bring their own interpreters, take a long time to book an appointment, do not spend enough time with patients, and do not explain things enough to patients |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

Not enough care coordinators who at the point of care involved with care |

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

Organizational |

|

Limited space for other providers to see patients after primary care provider visit |

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

Lack of communication between provider and patient |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

A long time for the health plan to approve referrals |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

Systems |

|

No behavioral health specialists accept private insurance for behavior health problems in a small town |

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

Lack of specialty care, particularly pediatric specialty care |

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

Health plans claim a data lag of 2-3 months |

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

Information does not flow freely between systems because of different electronic health records systems or Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act issues |

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

Lack of resources in the community |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

Care coordination activities are not reimbursed because it takes time to coordinate care |

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

Geographic barrier in the rural area |

|

|

|

√ |

At the provider level, communication between primary care and specialists was a barrier. One participant indicated, “We don’t get feedback from the specialist”. Lack of communication between the provider and patient was also common. For example, patients could have limited English proficiency or low health literacy, while providers lacked time or skill to provide adequate information. At the systems level, lack of reimbursement for care coordination was a barrier. One participant stated, “You don’t get paid for care coordination”.

The rural FQHC had other barriers like BHCs providing more services to adults than children. Because of specialist limitations, they had to refer patients to urban centers, which could also be a barrier.

Definition of care coordination

|

Function |

Key Word |

|

Frequency |

|

Noun |

Patient(s) |

|

20 |

|

Family/families |

|

7 |

|

|

Team |

|

3 |

|

|

Need(s), needs met |

|

15 |

|

|

Resources |

|

3 |

|

|

Options |

|

1 |

|

|

Education |

|

2 |

|

|

Empowerment |

|

1 |

|

|

Communication |

|

2 |

|

|

Modified noun |

Multidisciplinary team/group |

|

3 |

|

Patient-centered medical home |

|

3 |

|

|

Best health outcome |

|

1 |

|

|

Best services |

|

1 |

|

|

Correct care |

|

1 |

|

|

Full cycle |

|

1 |

|

|

Good outcome |

|

1 |

|

|

Good understanding |

|

1 |

|

|

Holistic approach |

|

1 |

|

|

Quality care |

|

1 |

|

|

Whole health |

|

1 |

|

|

Verb |

Collaborate |

|

1 |

|

Connect |

|

2 |

|

|

Educate |

|

1 |

|

|

Empower |

|

1 |

|

|

Follow through |

|

3 |

|

|

Follow up |

|

3 |

|

|

Involve |

|

3 |

|

|

Interact |

|

1 |

|

|

Make sure |

|

11 |

|

|

Provide |

|

5 |

|

|

Take care |

|

6 |

|

|

Work together |

|

2 |

|

|

Adjective |

Cost-effective |

|

1 |

|

Internal/external |

|

1 |

|

|

Physical, mental, emotional and spiritual |

|

2 |

|

|

Quality-based |

|

1 |

|

|

Whole |

|

3 |

|

|

Adverb |

Holistically |

|

1 |

|

Internally/externally |

|

1 |

|

|

Timely |

|

1 |

|

|

Together |

|

1 |

|

|

Other phrase |

Best experience in medicine |

|

1 |

|

Beyond the walls of clinics |

|

1 |

|

|

Close any gaps |

|

1 |

|

|

Close the loop |

|

1 |

|

|

Everyone is talking to everyone |

|

1 |

|

|

From top to bottom |

|

1 |

|

|

Medical and nonmedical needs |

|

1 |

|

|

Optimal health and wellbeing |

|

2 |

|

|

Under one umbrella |

|

1 |

Table 4: Key words by function and frequency for definition of care coordination by urban and rural federally qualified health center personnel.

Roles of care coordinators

Satisfaction with care coordination

DISCUSSION

Participants from urban and rural FQHCs valued teamwork that included patients and families as a facilitator for care coordination. Involving patients and families in the care team is essential, particularly with pediatric patients [24,29,30]. Both FQHCs also integrated primary care and behavioral health and were working to integrate nutrition, dentistry, and pharmacy services. Previous research indicates coordinate care is easier when multiple services are together. Both FQHCs had similar barriers to care coordination. Lack of communication between the provider and patient or between the provider and specialist, emergency department, or hospital was common. To build good partnerships, specialty care should be part of the care team. Although technology may alleviate this problem, physicians believe EHRs negatively impact interactions [31] and only facilitate care coordination within a practice, not between practices and settings [28]. Our participants indicated the ECW helped with internal communication, but financial incentives for coordination were lacking.

To meet patient needs, partnerships must exist within and outside FQHCs. A constant relationship among patients, families, and healthcare providers enhances care coordination [32,33] and positively impacts patient health [34]. Using resources outside the clinic is key for helping patients. Thus, FQHCs and other providers should build long-term partnerships with community organizations. Conceptual frameworks are one way to create partnerships [22,35]. The Ecological Model, served as this study’s framework, illustrates layers of partnerships and a medical neighborhood to address childhood health conditions. To implement care coordination activities, as was recommended by this study, multiple layers of partnerships should be built, and all partners should work together and influence each other, which is aligned with the Ecological Model. The partners can be internal or external, including providers and their staff members, patients and their families and social and community services. The team approach and integration of services are two facilitators of care coordination services identified by the interviewees in this study, and both of these facilitators require partnership building. One of the most important tasks for the care coordinator is to build partnerships with patients and their families and the services that the care coordinator refers them to. Definitions of care coordination were diverse and based on practice and experience. Based on their definitions, some participants had a better understanding of care coordination than others; however, occupational background of the participants was not a contributory factor in their defining care coordination. Previous studies also found different people had different definitions [15,16]. Common keys words of patient(s) need(s), and make sure aligned with facilitators to care coordination. However, family or team was rarely used.

For one participant, care coordination was like case management because practice was driven by health plans. Thus, the term, care coordination, could be used differently by similar programs or agencies, causing confusion. Although defining case management is not in the scope of this research, it is worth discussing the similarities and differences between care coordination and case management to provide a better picture of care coordination in a primary care setting that cares for children with complex chronic diseases. It is also important to point out that different organizations/professions may look at case management and care coordination differently. Both care coordination and case management are intended to address fragmentation in healthcare delivery [16,36] and are strategies to manage chronic disease between primary care and other healthcare settings [16,37]. Care coordination is a process to deliberately organize patient care plans involving multidisciplinary teams and diverse services (including health and social services) to achieve appropriate healthcare delivery and optimal health outcomes, and communication is the key for teams and services to exchange information [16,38-40]. In a PCMH/FCMH setting, primary care providers play a vital role in the process of care coordination [38,40]. During the care coordination process, there are many interventions, and case management is one care coordination intervention that helps patients and their families determine their medical and social needs [16,38]. The Agency for Health and Research Quality adopted a definition for case management that “implicitly enhances care coordination through the designation of a case manager whose specific responsibility is to oversee and coordinate care delivery [targeted to] high-risk patients [with a] diverse combinations of health, functional, and social problems” [16]. Since care coordination is relatively new, FQHCs need to establish differences between care coordination and case management and adopt a working definition of care coordination. Training on care coordination may eliminate confusion and promote teamwork. One FQHC in our study had a chart where dental assistants discussed what care coordination meant to them. Other FQHCs could use similar activities.

Care coordinators in pediatric settings may reduce costs, so they are recommended for the care team [24,29,41,42]. Although both FQHCs had care coordinators, they were like case managers at the urban FQHC. At the rural FQHC, the referral coordinator and care coordinator were the same. Because health plans decide on reimbursement, care coordinator’s responsibilities will not change unless FQHCs find other payment methods or health plans change care coordination. Most health plans practice a fee-for-service model, but it creates barriers between primary care and other providers. A value-based payment model may be better for FQHCs [43]. More research is needed on this payment model for FQHCs.

The current study had several limitations. The two FQHCs may not be representative of other FQHCs. We focused only on FQHC personnel; patients and families may have different views about care coordination. Further, we did not collect clinic data or consider outcomes of care coordination. The rural FQHC in this study was in a county, which used to be a rural county. However, due to economic development and expansion, the county is centrally located between two metro areas. Debate has occurred on whether the county should be considered a rural county or rural-urban county. Although it is still known as a center of American agriculture, the County lacks a truly rural feature, and this possibly impacts findings. Future research should include studies with more FQHCs, and the effect of FQHC location on the family’s level of engagement should be investigated by the following study.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings suggested neither the personnel’s occupational title nor urban or rural FQHC location was a contributory factor to affect understanding of care coordination. In addition to behavioral health, both FQHCs were working to integrate nutrition, dentistry, and pharmacy services. To improve outcomes of care coordination, FQHCs should have a working definition of care coordination, build partnerships, and explore the feasibility to reimburse care coordination activities. To effectively treat pediatric patients from low-income or minority families, FQHCs need to also address nonmedical needs like lifestyle changes and social and cultural needs. Such endeavors go beyond clinic walls. Teamwork between FQHC personnel and patients and families is necessary to improve pediatric health outcomes.

REFERENCES

- American Academy of Pediatrics (2016) Percentage of US children who have chronic health conditions on the rise. AAP, Illinois, USA.

- Focus for Health (2019) Chronic Illness and the State of Our Children’s Health. Focus for Health, Oakland, USA.

- Bonds RS, Asawa A, Ghazi AI (2014) Misuse of medical devices: a persistent problem in self-management of asthma and allergic disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 114: 63-76.

- Butz AM, Kub J, Bellin MH, Frick KD (2013) Challenges in providing preventive care to inner-city children with asthma. Nurs Clin North Am 48: 241-257.

- Koinis-Mitchell D, Kopel SJ, Salcedo L, McCue C, McQuaid EL (2014) Asthma indicators and neighborhood and family stressors related to urban living in children. Am J Health Behav 38: 22-30.

- Oraka E, Iqbal S, Flanders WD, Brinker K, Garbe P (2013) Racial and ethnic disparities in current asthma and emergency department visits: findings from the National Health Interview Survey, 2001-2010. J Asthma 50: 488-496.

- Quinn K, Kaufman JS, Siddiqi A, Yeatts KB (2010) Stress and the city: housing stressors are associated with respiratory health among low socioeconomic status Chicago children. J Urban Health 87: 688-702.

- Williams MV, Baker DW, Honig EG, Lee TM, Nowlan A (1998) Inadequate literacy is a barrier to asthma knowledge and self-care. Chest 114: 1008-1015.

- Van Cleave J, Gortmaker SL, Perrin JM (2010) Dynamics of Obesity and Chronic Health Conditions Among Children and Youth. JAMA 303: 623-630.

- Poitras ME, Maltais ME, Denommé LB, Stewart M, Fortin M (2018) What are the effective elements in patient-centered and multimorbidity care? A scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 18: 446.

- Looman WS, Presler E, Erickson MM, Garwick AE, Cady RG, et al. (2013) Care coordination for children with complex special health care needs: the value of the advanced practice nurse’s enhanced scope of knowledge and practice. J Pediatr Health Care 27: 293-303.

- Tschudy MM, Raphael JL, Nehal US, O’Connor KG, Kowalkowski M, et al. (2016) Barriers to care coordination and medical home implementation. Pediatrics 138: 2015-3458.

- Peikes D, Zutshi A, Genevro J, Smith, K, Parchman, M, Meyers, D (2012) Early Evidence on the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ publication 12-0020-EF.

- Bodenheimer T (2008) Coordinating care--a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med 358: 1064-1071.

- McDonald KM, Schultz E, Albin L, Pineda N, Lonhart J, et al. (2010) Care Coordination Atlas Version 3. Rockville, (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ publication 11-0023-EF.

- McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, Lewis R, Lin N, et al. (2007) Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ publication 04(07)-0051-7.

- Greene AM (2017) Early findings on care coordination in capitated Medicare-Medicaid plans under the Financial Alignment Initiative [Internet]. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

- HRSA Health Center Program (2018) Health Resources and Services Administration. HRSA Health Center Program, Rockville, USA.

- Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Jaén CR, Crabtree BF, et al. (2010) Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med 25: 601-612.

- Alfero C, Barnhart T, Bertsch D, Graff S, Hill T, et al. (2013) National Rural Health Association Policy Brief: the future of rural health. National Rural Health Association.

- Derrett S, Gunter KE, Nocon RS, Quinn MT, Coleman K, et al. (2014) How 3 rural safety net clinics integrate care for patients: a qualitative case study. Med Care S39-47.

- Hamburger R, Berhane Z, Gatto M, Yunghans S, Davis RK, et al. (2015) Evaluation of a statewide medical home program on children and young adults with asthma. J Asthma 52: 940-948.

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K (2008) Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice (4thedn). John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, USA. Pg no: 592.

- Antonelli RC, McAllister JW, Popp J (2009) Making care coordination a critical component of the pediatric health system: A multidisciplinary framework. The Commonwealth Fund, Washington, DC, New York, USA.

- Beck AF, Huang B, Chundur R, Kahn RS (2014) Housing code violation density associated with emergency department and hospital use by children with asthma. Health Aff (Millwood) 33: 1993-2002.

- Klein MD, Beck AF, Henize AW, Parrish DS, Fink EE, et al. (2013) Doctors and lawyers collaborating to HeLP children--outcomes from a successful partnership between professions. J Health Care Poor Underserved 24: 1063-1073.

- Wagner Ed, Thomas-Hemak L (2013) Closing the loop with referral management. Group Health Research Institute, Washington, USA.

- O’Malley AS, Grossman JM, Cohen GR, Kemper NM, Pham HH (2010) Are electronic medical records helpful for care coordination? Experiences of physician practices. J Gen Intern Med 25: 177-185.

- Cooley WC, McAllister JW (2004) Building medical homes: improvement strategies in primary care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics 113: 1499-1506.

- Wood D, Winterbauer N, Sloyer P, Jobli E, Hou T, et al. (2009) A longitudinal study of a pediatric practice-based versus an agency-based model of care coordination for children and youth with special health care needs. Matern Child Health J 13: 667-676.

- Pelland KD, Baier RR, Gardner RL (2017) “It's like texting at the dinner table”: A qualitative analysis of the impact of electronic health records on patient-physician interaction in hospitals. J Innov Health Inform 24: 894.

- Gill JM, Mainous AG 3rd (1998) The role of provider continuity in preventing hospitalizations. Arch Fam Med 7: 352-357.

- Gill JM, Mainous AG 3rd, Nsereko M (2000) The effect of continuity of care on emergency department use. Arch Fam Med 9: 333-338.

- Mountain Park Health Center (2016) Mountain Park Health Center: A key piece in the game of life. Mountain Park Health Center, Arizona, USA.

- Taylor EF, Lake T, Nysenbaum J, Peterson G, Meyers D (2011) Coordinating Care in the Medical Neighborhood: Critical Components and Available Mechanisms. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Maryland, USA.

- Woodward J, Rice E (2015) Case management. Nurs Clin North Am 50; 109-121.

- Tortajada S, Giménez-Campos MS, Villar-López J, Faubel-Cava R, Donat-Castelló L, et al. (2017) Case Management for Patients with Complex Multimorbidity: Development and Validation of a Coordinated Intervention between Primary and Hospital Care. Int J Integr Care 17: 4.

- Ziring PR, Brazdziunas D, Cooley WC, Kastner TA, Kummer ME, et al. (1999) American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Children with Disabilities. Care coordination: integrating health and related systems of care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics 104: 978-981.

- Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, et al. (2003) Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ 327: 1219.

- Lipkin PH, Alexander J, Cartwright JD, Desch LW, Duby JC, Edwards DR, et al. (2005) Care coordination in the medical home: Integrating health and related systems of care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics 116: 1238-1244.

- Antonelli RC, Stille CJ, Antonelli DM (2008) Care coordination for children and youth with special health care needs: a descriptive, multisite study of activities, personnel costs, and outcomes. Pediatrics 122: 209-216.

- Kelly RP, Stoll SC, Bryant-Stephens T, Janevic MR, Lara M, et al. (2015) The influence of Setting on Care Coordination for Childhood Asthma. Health Promot Pract 16: 867-877.

- Donlon R (2017) State Medicaid Agencies Venture into Value-Based Purchasing with Federally Qualified Health Centers. National Academy for State Health Policy Set 26.

Citation: Chartrand HZ, Rosales CB, MacKinnon NJ (2019) Understanding of Care Coordination by Healthcare Providers and Staff at Federally Qualified Health Centers: A Qualitative Analysis. J Community Med Public Health Care 6: 041.

Copyright: © 2019 Hong Z Chartrand, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.