A Community-Driven Social Marketing Campaign to Reduce Childhood Obesity

*Corresponding Author(s):

Kristy M MedinaNew York Presbyterian Hospital, Ambulatory Care Network, New York, United States

Abstract

Background

Obesity disproportionately affects Latino children in the United States. In New York City, 40% of Latino children are overweight and obese, compared to 17% of children nationally. CHALK (Choosing Healthy & Active Lifestyles for Kids) is a childhood obesity prevention program that was created by community members of the Washington heights and in wood neighborhoods of NYC to address increased prevalence of obesity.

Community context

Children are primarily Latino (80.3%), with Dominican and Mexican roots. The majority of the community has limited English proficiency and 38.6% of Latino children live in poverty.

Methods

CHALK recruited community members to form a campaign, Vive tu Vida/Live your Life, to create user-generated social marketing message and strategy. Campaign members engaged community entities including businesses, elected officials and individuals.

Outcomes

At the end of five years, CHALK had recruited 64 campaign participants. 58% reported they were actively promoting the program objectives. Through events, work of campaign participants, and mini-grants, community members were exposed to the social marketing campaign. CHALK and the Task Force created a message in which the community felt ownership of the mission, vision and messages.

Conclusion

Through the work and support of the Vive tu Vida Task Force, CHALK created a culturally appropriate message. CHALK continued to disseminate the campaign and has expanded into venues beyond its original reach, including schools, faith-based organizations, non-profit organizations, and healthcare settings. Applying a socio-ecological framework and giving ownership and control to community stakeholders are crucial to creating a sustainable community social marketing health-promotion campaign.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND

The causes of childhood obesity are complex. Associations have been made between obesity, socio-economic status and the built environment-food deserts; prevalence of fast food establishments; walk ability; and safety-in addition to genetic predispositions [3,4]. Different cultural perceptions about weight can also impact eating and exercise behaviors, making a tailor-made approach to childhood obesity prevention essential. The socio-ecological model is a multi-factorial approach necessary to create cross-sector change in the prevention of childhood obesity within a community setting. This model considers the multiple factors that influence childhood obesity [5]. Interventions such as Shape Up Somerville, 5-4-3-2-1-GO! and 5210 Let’s Go!, address obesity from a holistic, lifestyle perspective by engaging schools, businesses and communal organizations for social marketing message exposures, and in some cases, supportive environmental changes [6,7]. Shape up Somerville has demonstrated its efficacy with a decrease in Body Mass Index (BMI) scores over time [8].

While these interventions have proven successful in their respective communities, there is little in the literature which provides evidence for community-generated-owned and disseminated messages to combat childhood obesity. According to Kretzmann and McKnight, highlighting communities’ capacities and not merely their needs can create a sustainable impact [9]. A community developed, community driven message could create a larger impact over time among residents as participants would have a voice in program development.

COMMUNITY CONTEXT

The Washington Heights/Inwood (WaHI) community consists primarily of Dominican and Mexican immigrants. The majority of children, 80.3%, are Latino; over 30% of all children are living in poverty, with the highest incidence of childhood poverty occurring in Latinos (38.6%) [10,11]. Nearly 40% of children are food insecure, with limited access to Emergency Food Providers including soup kitchens and food pantries. In 2011, over 39,000 individuals received SNAP benefits in the community [11].

Although recent data shows the rate of childhood obesity overall in New York City has declined, prevalence of obesity remains, on the whole, higher than the national average and steadfast in the Latino population [10]. WaHI are the epicenters of the NYC obesity epidemic. WaHI, which is made up of 71.7% Latino residents [2], has some of the highest percentages of children with obesity in NYC in addition to being a socioeconomically disadvantaged community with correspondingly high rates of poverty and food insecurity. Both these issues are connected to food access, malnutrition and obesity rates [12]. In 2011, 26.5% of Latino children in Washington Heights aged 5-14 years were classified as overweight and obese, compared to only 16.1% of Caucasians in NYC [2].

Due to the large population of Dominican immigrants in the WaHI area, there are many “mom and pop” restaurants that serve Dominican-style meals. The national dish of the Dominican Republic, “La Bandera”, consists of rice, beans, meat, and fried plantains. Generally, many starchy vegetables, like yucca, cassava, and plantains are consumed on a regular basis, and incorporation of dark greens is limited. Portions served both in the home and at restaurants are typically larger than recommended by the USDA.

Geographically, WaHI has a mixed terrain, with multiple, small public parks and recreation facilities, totaling 701 acres, or about one acre per 50 children. Despite the variety of open space, utilization may be hindered by perceived safety in the neighborhood. In 2013, 2,101 felonies were committed, with 869 classified as violent [10].

About 39% of inhabitants have limited English proficiency, demonstrating a clear need for social marketing messaging and materials to be disseminated in Spanish more frequently than English [10].

METHODS

Community engagement and campaign creation

At the initiation of the effort, a call for community participants was issued in order to ensure community engagement and collaboration in the creation of the message. This group became the Vive tu Vida/Live Your Life Task Force. The Task Force members were a diverse group of individuals representing adult multidisciplinary community stakeholders. The Task Force members included community members, activists, and representatives from local partnering community based organizations, leadership of community churches, artists, and local food establishments. These Task Force members then led the coalition to create a captivating campaign title: “Vive tu Vida: Energía, balance, y Acción/Live your life: energy, balance, and action”. Due to the large Latino community, it was critical to Task Force members to create the message first in Spanish, and then translate it into English. They chose English/Spanish cognates as descriptives, with the idea that the more similar the English and Spanish message was, the better the community would receive it. CHALK assisted the Task Force with the development of the slogan and provided formal training to the key Task Force members in social marketing.

The Community Task Force identified optimal public health messaging for the Washington heights community. They expanded the “8 Healthy Habits of Kids” from the healthy children healthy futures program [13] to the “10 healthy habits of kids” (Figure 1). The social marketing campaign focused on one habit per calendar month; the other two months promoted the overall campaign. Messages were piloted with several small focus groups with selected children, parents, and organizations before being mass distributed.

February: Eat plenty of vegetables and some fruit every day

March: Get enough sleep and eat breakfast

April: Switch to low-fat (1% or less) milk, cheese, and yogurt

May: Do something healthy every day that makes you feel good

June: Drink water instead of soda or juice

September: Turn off the screens and Live your Life!

October: Snack on healthy foods

November: Eat smaller amounts

December: Eat less fast food

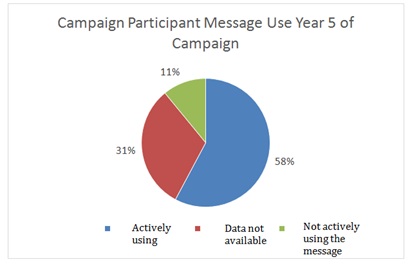

The “10 healthy habits” became CHALK’s program objectives, and together with the Task Force members, CHALK co-organized the community campaign and coalition to combat childhood obesity on the ground level, enlisting businesses and organizations, and engaging community residents. Outcomes of interest included number of community businesses that agreed to sign the CHALK/Vive tu Vida campaign pledge; number of community members who attended large-scale health promotion events; frequency of healthy habit use amongst community campaign participants; and use of healthy habit messaging after year 5 of the Vive tu Vida campaign (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Campaign participants message use years 5 of campaign.

Figure 2: Campaign participants message use years 5 of campaign.Business recruitment & school participation

Schools promoted the 10 habits of healthy kids by distributing newsletters, creating bulletin boards and tailored nutrition education classes to communicate the message to children, staff and parents. Fitness organizations would incorporate healthy habit messaging and distributed promotional materials to community members. Businesses and individuals tailored the Vive tu Vida/Live your life message to suit their specific needs; for example, local grocers used “shelf-talkers” to promote water instead of soda or juice at a food store or bodega. At the same time, the Task Force met monthly to plan larger, community-wide events. In the first four years, CHALK/Vive tu Vida hosted three large events attracting up to 800 youth each for nutrition education and physical activity.

Mini-grants:

Outcomes

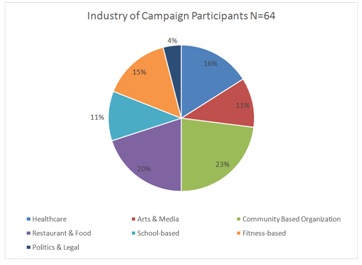

Figure 3: Industry of campaign participants N=64.

Figure 3: Industry of campaign participants N=64.Of the 64 campaign participants, 75% responded to a one-year post survey. 43.7% of responders reported that they had promoted at least one of the 10 healthy habits of kids and provided examples. For example, bodegas promoted healthier snacks by providing healthier checkout items; instead of candies and packaged items, participants stocked fruits by the checkout registers.

Of the 64 participants, 68.7% (n=44) responded to a second year follow up survey about campaign message usage. 58% (n=37) reported that they were actively using the message and 11% (n=7) responded that they were not, as shown in figure 3.

Campaign participants promoted the message and integrated healthy habits in a variety of ways including: traditional forms of advertising such as billboards on highways, signs in supermarket aisles, physical activity programming, and encouraging active community lifestyles. Others adopted healthy snack policies in their child programming or created healthy menu options for customers.

Mini-grants:

Electronic message dissemination

Built environment:

Interpretation

Initially, it was important to engage with local businesses in the neighborhood to establish credibility and visibility in the community. While the majority of campaign participants promoted the “10 Habits of Healthy Kids”, promotion styles varied. Additionally, businesses were not required to promote all 10 habits, as they may not have related directly to their business needs.

Since schools are epicenters of a community, collaboration with elementary schools has been key to dissemination of the message and campaign. CHALK’s school program utilizes the Vive tu Vida messaging and has created a healthy lifestyles curriculum, Classroom Connections, which is mapped to Common Core Learning Standards (CCLS). Additionally, CHALK’s adopted the Just Move™ in-class activity cards that promote kinesthetic learning with quick bursts of activity throughout the day. This program has been proven to increase physical activity to exceed the New York State Physical Education mandate of 150 minutes per week [14]. CHALK’s school program implementation and evaluation was captured via an Environmental Scan Survey, which evaluates 4 years of school wellness environment throughout the intervention. CHALK in the schools has been able to increase awareness and implementation of wellness policies, increase health promotion, and sustainable environmental changes to promote healthy lifestyles among partnered district 6 schools.

However, by year 5, only 58% of campaign participants were actively promoting the 10 healthy habits. Also, by that time, city-wide organizations were focusing on providing resources and incentives for owners of large businesses. Therefore, CHALK/Vive tu Vida focused on school and clinical settings, merging with a school-based obesity prevention program, in addition to continuing the community work, and even extending to the hospital’s outpatient clinics. This ensured that the program disseminated consistent obesity prevention health messaging across the continuum of a child’s life including the community, school, faith-based organizations, and clinical pediatric practices.

CHALK has been involved in community development opportunities throughout the neighborhood to create a more sustainable change. Permanent neighborhood fixtures like greenmarkets play streets, bike lanes and community gardens will help keep programming alive and encourage community members to participate in obesity prevention/health promotion activities as a part of daily life. Engaging other stakeholders has not only provided a rich environment for collaboration and collective impact, but it also avoids duplicating efforts of larger, city-wide organizations.

The CHALK program continued to disseminate the 10 healthy habits created by the Vive tu Vida campaign and focus on community building and engagement. The social marketing calendar is used throughout all aspects of CHALK programming, evolving its message and tailoring it to other target audiences. The campaign and our community driven initiative have been critical in continued development and expansion of the obesity prevention efforts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research was supported by the New York State Department of Health, Division of Chronic Disease Prevention and Adult Health, contract #C022499.

REFERENCES

- Ramchand R (2017) Epidemiologist RAND Corporation: Congressional testimony before the senate appropriations committee preventing veterans suicides. Epidemiologist RAND Corporation, California, USA.

- S. Department of Veterans Affairs (2016) Suicide among veterans and other Americans Office of Suicide Prevention. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, USA.

- US Department of Veteran Affairs (2016) VA Conducts Nation’s Largest Analysis of Veteran Suicide. Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, US Department of Veteran Affairs, USA.

- https://www.militarytimes.com/veterans/2016/07/07/new-va-study-finds-20-veterans-commit-suicide-each-day/

- Lam CA, Sherbourne C, Gelberg L, Lee ML, Huynh AK, et al. (2017) Differences in depression care for men and women among veterans with and without psychiatric comorbidities. Womens Health Issues 27: 206-213.

- Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, Gunn J, Kerse N, et al. (2010) Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med 8: 348-353.

- Bossarte RM, Knox KL, Piegari R, Altieri J, Kemp J, et al. (2012) Prevalence and characteristics of suicide ideation and attempts among active military and veteran participants in a national health survey. Am J Public Health 102: 38-40.

- https://www.va.gov/budget/docs/summary/fy2018VAbudgetInBrief.pdf

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (2017) Depression and veterans. National Alliance on Mental Illness, Virginia, USA.

- Department of Veterans Affairs (2016) Facts about veteran suicide. Department of Veterans Affairs, USA.

- http://www.ptsd.ne.gov/what-is-ptsd.html

- https://www.ptsd.va.gov/PTSD/public/assessment/ptsd-measured.asp

- Steel JL, Dunlavy AC, Stillman J, Pape HC (2011) Measuring depression and PTSD after trauma: Common scales and checklists. Injury 42: 288-300.

- https://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/treatment/therapy-med/treatment-ptsd.asp

- Chevalier A, Richards S (2017) Holographic kinetics for a child suffering from autism with extreme aggressive behavioral disorder. J Altern Complement Integr Med 3: 1-4.

- Schlottmann A, Ray ED, Surian L (2012) Emerging perception of causality in action-and-reaction sequences from 4 to 6 months of age: Is it domain-specific? J Exp Child Psychol 112: 208-230.

- Green C (2003) The Lost Cause: Causation and the Mind-Body Problem. Oxford Forum, Oxford, UK.

- Bunge M (1959) Causality: the place of the causal principle in modern science. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

- Galison PL (1979) Minkowski’s Space-Time: From Visual Thinking to the Absolute World. University of California Press, Berkeley, California, USA.

- Walter SA (1999) Minkowski, mathematicians and the mathematical theory of relativity. In: Goenner, H, Renn J, Ritter J, Sauer T (eds.). The Expanding Worlds of General Relativity. Birkhäuser 45-86.

- Penrose R (2005) Minkowskian geometry. In: Penrose R (ed.). Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Jonathan Cape, London, UK.

- Weinberg S (2013) The Quantum Theory of Fields. Cambridge University Press, England, UK.

- Forsdyke DR (2009) Samuel Butler and human long term memory: Is the cupboard bare? J Theor Biol 258: 156-164.

- Andrew AM (1997) The decade of the brain ? further thoughts. Kybernetes 26: 255-264.

- Pribram KH, Meade SD (1999) Conscious awareness: Processing in the synaptodendritic web. New Ideas in Psychology 17: 205-204.

- Pribram KH (1999) Quantum holography: Is it relevant to brain function? Information Sciences 115: 97-102.

- Vandervert LR (1995) Chaos theory and the evolution of consciousness and mind: A thermodynamic-holographic resolution to the mind-body problem. New Ideas in Psychology 13: 107-127.

- Berger DH, Pribram KH (1992) The relationship between the Gabor elementary function and a stochastic model of the inter-spike interval distribution in the responses of visual cortex neurons. Biol Cybern 67: 191-194.

- Pribram KH (2004) Consciousness Reassessed. Mind and Matter 2: 7-35.

- Gabor D (1972) Holography, 1948--1971. Science 177: 299-313.

- Borsellino A, Poggio T (1972) Holographic aspects of temporal memory and optomotor responses. Kybernetik 10: 58-60.

- Bókkon I (2005) Dreams and neuroholography: An interdisciplinary interpretation of development of homeotherm state in evolution. Sleep and Hypnosis 7: 61-76.

- Gabor D (1968) Holographic Model of Temporal Recall. Nature 217: 584.

- Mikulincer M Orbach I (1995) Attachment styles and repressive defensiveness: The accessibility and architecture of affective memories. J Pers Soc Psychol 68: 917-925.

- Apter A, Gothelf D, Orbach I, Weizman R, Ratzoni G, et al. (1995) Correlation of suicidal and violent behavior in different diagnostic categories in hospitalized adolescent patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34: 912-918.

- Waltz TJ, Campbell DG, Kirchner JE, Lombardero A, Bolkan C, et al. (2014) Veterans with depression in primary care: provider preferences, matching, and care satisfaction. Fam Syst Health 32: 367-377.

- Reist C, Mee S, Fujimoto K, Rajani V, Bunney WE, et al. (2017) Assessment of psychological pain in suicidal veterans. PLoS One 12: 0177974.

- Tossani E (2013) The concept of mental pain. Psychother Psychosom 82: 67-73.

- Yi L, Wang J, Jia L, Zhao Z, Lu J, et al. (2012) Structural and Functional Changes in Subcortical Vascular Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Combined Voxel-Based Morphometry and Resting-State FMRI Study. PLoS One 7: 44758.

- Bellace M, Williams JM, Mohamed FB, Faro SH (2013) “An FMRI Study of the Activation of the Hippocampus by Emotional Memory. Int J Neurosci 123: 121-127.

- Fox M, Pascual-Leone A (2012) Intrinsic Functional Connectivity with the Subgenual Cingulate Predicts Clinical Efficacy of TMS Targets for Depression (P01.188). Neurology 78.

- Chiaravalloti ND (2014) Application of Functional Neuroimaging to Evaluating the Efficacy of Cognitive Rehabilitation in Neurological Populations. Imaging in Medicine 6: 9-11.

- Fayed N, Andrés E, Viguera L, Modrego PJ, Garcia-Campayo J (2014) Higher glutamate+glutamine and reduction of N-acetylaspartate in posterior cingulate according to age range in patients with cognitive impairment and/or pain. Acad Radiol 21: 1211-217.

- Amen DG, Prunella JR, Fallon JH, Amen B, Hanks C (2009) A comparative analysis of completed suicide using high resolution brain SPECT imaging. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 21: 430-439.

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/fy2018/budget.pdf

- Reistad B (2015) New bill provides VA accountability. The American Legion, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA.

- Amen DG, Trujillo M, Newborn A, Willeumier K, Tarzwell R, et al. (2011) Brain SPECT Imaging in Complex Psychiatric Cases: An Evidence-Based, Underutilized Tool. Open Neuroimag J 5: 40-48.

Citation: Pitsirilos-Boquín S, Medina KM, Squillaro A, Gonzalez JC, Nieto AR, et al. (2017) A Community-Driven Social Marketing Campaign to Reduce Childhood Obesity. J Community Med Public Health Care 4: 033.

Copyright: © 2017 Stephanie Pitsirilos-Boquín, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.