A Comparative Study Evaluating Improvement of Swallowing ability of Elderly Patients who Admitted to the Internal Medicine Department with Dysphagia using Fujishima’s Dysphagia Grading System

*Corresponding Author(s):

Mototaka NiwanoDepartment Of General Medical, Kikuna Memorial Hospital, 4-4-27 Kikuna, Kohoku-ku, Yokohama City, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan

Tel:+81 0454027111,

Fax:+81 0454322742

Email:niwano@kmh.or.jp

Abstract

This comparative study evaluated the improvement in swallowing ability in elderly patients admitted with dysphagia. Between 2013 and 2018, 961 inpatients with dysphagia, aged ≥65, were admitted to the internal medicine department of our hospital. We divided these patients into two groups based on whether pneumonia was (n=691) or was not (n=270). We focused on patients with a Fujishima’s dysphagia grading system (Gr) ≤5 at the beginning of the intervention of the Nutrition Support Team (NST). Any changes in swallowing capacity were analyzed according to sex, age (male ≥80, female ≥85) and nutritional administration method. For the patients with a Gr≤5, the improvement rate was 10%-20%, regardless of sex, age and pneumonia status.

Of the male patients aged ≥80 in the pneumonia group, one out of four died in the hospital, two out of five were discharged on an oral diet, and the rest required Artificial Hydration and Nutrition (AHN), while for the female patients aged ≥85, one out of six died, tree out of five were discharged on an oral diet and the rest required AHN. The NST may contribute to the introduction of AHN as a concrete option.

Keywords

Artificial hydration and nutrition; Dysphagia; Elderly patient; Fujishima’s dysphagia grading system; Nutrition support team

Introduction

Our hospital, which was established in 1991 in Kohoku-ku, Yokohama City, Kanagawa Prefecture, has 218 hospital beds and accepts 7,000 ambulances per year, including a number of elderly patients. Our Nutrition Support Team (NST), which was established in June 2005, is a multidisciplinary collaboration team composed of doctors, nurses, registered dietitians, physiotherapists, pharmacists and dentists. The NST examines 15-20 patients in all the wards on Thursdays at noon. In the hospital internal medicine department, we make significant efforts to manage discharges and find sanitariums for elderly patients with dysphagia. The swallowing function at the beginning and end of the NST’s interventions are analyzed using Fujishima’s dysphagia grading system (Table 1) [1], and the appropriate nutritional administration method is decided at the end of nutritional support.

|

1. Severe (Mainly alternative nutrition) |

Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 |

Oral intake not possible (dysphagia therapy not indicated) Only Indirect dysphagia therapy without oral intake allowed Direct dysphagia therapy with oral intake allowed |

|

2. Moderate (Oral intake with alternative nutrition) |

Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6 |

Minimal (less than one meal) oral intake possible Partial (one or two meals a day) oral intake possible Oral intake possible for all meals but still require some alternative nutrition |

|

3. Mild (Oral intake only)

|

Grade 7 Grade 8

Grade 9 |

Oral intake of dysphagia diet possible for all meals Oral intake of restricted diet possible (specific food items that are difficult to swallow avoided) Oral intake of normal diet possible with supervision |

|

4. Normal |

Grade 10 |

Normal oral intake and swallowing function |

Table 1: Fujishima’s dysphagia grading system.

Materials and Methods

In the 5 years from January 2013 until 2018, 1,285 patients with dysphagia who needed a NST evaluation were admitted. 1,245 patients of these were aged ≥65 years, which is considered elderly according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Of these 1,245 elderly patients, 961 patients (77.2%) were admitted to the internal medicine department. They were then divided into two group according to whether pneumonia was or was not the primary diagnosis (the pneumonia and the non-pneumonia groups). At the end of the NST’s interventions, 18 (13 males and 5 females; 6.6%) out of 271patients with a Fujishima’s dysphagia grading system grade (Gr) ≥6 ( ability to take 3 dysphagia diet orally) died in the hospital due to worsening disease (9 had pneumonia, 2 had heart failure, 1 had cancer and 6 had other infections). The remaining patients were discharged from the hospital safely on an oral diet. We focused on the patients with a Gr≤5 (dysphagia diet intake ≤ 50% in the progress table).

As the average life expectancy in Japan in 2013 was 80.21 years for men and 86.61 years for women, we divided the patients by age as follows; males aged ≥80 or <80, and females aged ≥85 or <80. The patients were further separated into two groups according to their pneumonia status (the pneumonia and the non-pneumonia groups). For the NST evaluation, thoracic auscultation was first performed on the target patients, and if there was no abnormality, one of the swallowing evaluation tests were attempted. These included the Repetitive Saliva Swallowing Test (RSST) [2], Modified Water Swallowing Test (MWST), which involves swallowing 3mL of room temperature thickened water, or a Food Test (FT), which involves eating a teaspoon (3-4g) of jelly or pudding [3].

For patients with swallow function, jelly, a mixer meal and a dysphagia diet of minced food and thickened water were served. The patients’ swallow function was evaluated using the Fujishima’s dysphagia grading system. If a change in swallow function occurred, it was classified as an ‘improvement’ when the grade increased more than one grade and as ‘deterioration’ when the grade decreased at least one grade. If there was no change in the grade, it was classified ‘no change’.

The 2012 edition guidelines for decision-making in elderly care include items referring to artificial Hydration and Nutrition (AHN) [4]. AHN includes Enteral Nutrition (EN) and Parenteral Nutrition (PN). For EN, intestinal ducts are accessed through a Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrotomy (PEG) or by inserting a Nasogastric (NG) tube into the stomach or duodenum. Peripheral Parenteral Nutrition (PPN) refers to the intravenous infusion of nutrients through the peripheral veins of the limbs, while total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) is inserted through a central vein and requires a central catheter to be inserted into a thick vein near the heart, such as the internal jugular vein, the subclavian vein, or the femoral vein. TPN has the capacity to deliver a high-calorie infusion.

Statistical analyses were performed using the free software EZR [5]. Comparisons were conducted using the corresponding t-test. Continuous variables were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance, while categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. This study was approved by the hospital ethics committee (approval number 27-01) and patient data were unidentified.

Results

A total of 961 internal medicine department inpatients (mean age, 86.3±4.2 years) were included in this study.

Of those, 442 were males (mean age, 84.5±7.8 years) and 519 were females (mean age, 87.9±6.7 years). Regarding the primary diagnosis, 691 (71.9%) patients were diagnosed with pneumonia, 52 (5.4%) had urinary tract infections, 38 (4.0%) had stroke, 35 (3.6%) had endocrine metabolic disorders, 29 (3.0%) had other infections, 28 (2.9%) had heart failure, 25 (2.6%) had cancer, 15 (1.6%) had digestive diseases and 48 (5.0%) had other diagnoses.

A total of 801 patients were discharged alive (354 males, 447 females), of which 578 had a primary diagnosis of pneumonia. Of the remaining patients, the primary diagnosis was urinary tract infections in 48, stroke in 36, endocrine metabolic disorders in 33, other infections in 23, heart failure in 16, cancer in 14, digestive diseases in 13 and other diagnoses in 40. A total of 160 patients died in the hospital (88 males, 72 females), of which primary diagnosis was pneumonia in 113, heart failure in 12, other infections in 11, cancer in 11 and other diagnoses in 13. Of the 691 patients in the pneumonia group, 332 were males (mean age, 85.4±6. 6 years) and 359 were females (mean age, 87.9±6.3 years). Of the 270 patients in the non-pneumonia group, 110 were males (mean age, 82.9±7. 3 years) and 160 were females (mean age, 88.9±6. 8 years).

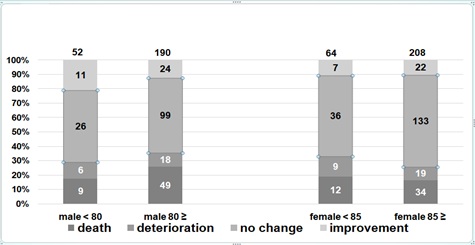

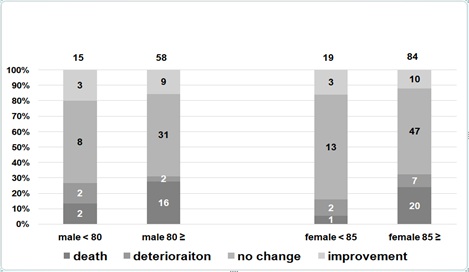

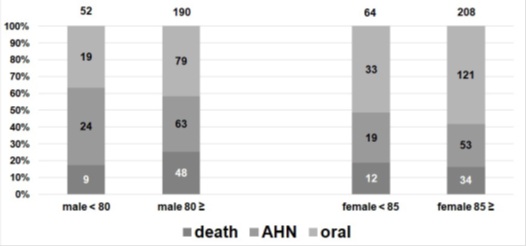

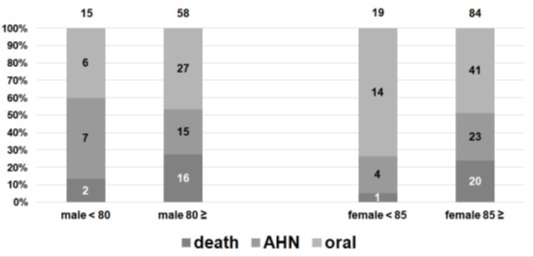

After the NST’s interventions, the rate of improvement of swallow function in the pneumonia and non-pneumonia groups with a Gr≤5 according to sex and age are shown in figures 1 and 2. The improvement rate of patients with a Gr≤5 in the pneumonia group was as follows; 11 out of 52 males (21.2%) aged < 80 versus 24 out of 190 males (12.6%) aged ≥80, and 7 out of 64 (10.9%) females aged < 85 versus 22 out of 208 (10.6%) females aged ≥85. The improvement rate of the patients with a Gr≤5 in the non-pneumonia group was as follows; 3 out of 15 (20%) males aged <80 versus 9 out of 58 (15.5%) males aged ≥80, and 3 out of 19 (15.8%) females aged <85versus 10 out of 84 (11.9%) females aged ≥85. The improvement rate in the patients with a Gr≤5 was 10%-20% regardless of sex, age and pneumonia status. The nutritional administration methods applied after the NST’s interventions in the pneumonia and non-pneumonia groups with a Gr≤5 according to sex and age is shown in figures 3 and 4.

Figure 1: The patients with a Gr≤5 of the pneumonia group changes of Gr according to sex and age.

Figure 1: The patients with a Gr≤5 of the pneumonia group changes of Gr according to sex and age.

Figure 2: The patients with a Gr≤5 of the non-pneumonia group changes of Gr according to sex and age.

Figure 2: The patients with a Gr≤5 of the non-pneumonia group changes of Gr according to sex and age.

Figure 3: The patients with a Gr≤5 of the pneumonia group nutritional administration methods according to sex and age after the NST’s interventions.

Figure 3: The patients with a Gr≤5 of the pneumonia group nutritional administration methods according to sex and age after the NST’s interventions.

Figure 4: The patients with a Gr≤5 of the non-pneumonia group nutritional administration methods according to sex and age after the NST’s interventions.

Figure 4: The patients with a Gr≤5 of the non-pneumonia group nutritional administration methods according to sex and age after the NST’s interventions.

Among the male patients aged ≥80 in the pneumonia group with a Gr≤5 (78.5%), one out of four died in the hospital, two out of five were discharged on an oral diet and the rest required AHN. Among the female patients aged ≥85 in the pneumonia group with a Gr≤5 (76.4%), one out of six died in the hospital, three out of five were discharged on an oral diet and the remainder needed AHN. For the comparison between the male patients with pneumonia aged ≥80 and the female patients with pneumonia aged ≥85, a statistically significant difference for discharge on an oral diet and hospital death was seen for sex, with worse findings for males. At the end of the NST’s interventions, there were some patients with a Gr≤5 who requested oral nutrition and refused AHN regardless of their pneumonia status. Clinically, in Japanese hospitals, patients and their families must decide to choose AHN.

Discussion

Diseases and conditions that increase the likelihood of developing dysphagia are as follows; cerebrovascular disorders, head injuries, neurological disorders, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases [6,7], a history of aspiration pneumonia, tumors, a recent operation, impaired consciousness, dementia and older age (≥65 years) [8]. Pneumonia is currently the fourth leading cause of death in Japan. Sixty percent of hospitalized patients with pneumonia are said to have aspiration pneumonia [9,10], and a rapid increase in cases of aspiration pneumonia has been reported [11]. It is known that the primary cause of aspiration pneumonia is dysphagia [8], 71% of elderly patients with pneumonia and 10% of non-pneumonia patients aspirate into the lungs at night [12].

In this study, patients in internal medicine were divided into two groups based on their primary diagnosis; the pneumonia and the non-pneumonia groups. In order to decide the nutritional administration method, it is essential for the patient's swallow function and degree of aspiration to be evaluated. According to the guidelines for treating swallow function (2012 edition by The Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Society of Japan), Video Endoscopic (VE) and Video Fluoroscopic (VF) examination of swallowing are recommended as the first choice. However, VE and VF require equipment and trained technicians. We there for used the RSST, the MWST, and the FT which are easily performed at the bedside. MWST and FT are said to have a sensitivity between 70% and 90%, and a specificity between 60% and 90% [13-15].

Although administering nutrition enterally, either through inserting a NG tube into the stomach or duodenum or through placing a PEG is often used for patients who have difficulty taking water and food orally, the PEG has not been shown to prolong the life of elderly patients in Europe and the United States.

One possible explanation is that in Europe and the United States, the belief that “if you can’t eat, your life is over,” which respects autonomy and an emphasis of the sanctity of life based on religion is popular. However, in Japan, the view that “death is nothing” is emphasized and there for life-prolonging treatment is performed without an understanding of aging and death in elderly patients. For adult patients who have difficulty with self-determination, the decision is left to the family. However, the range of the family is unclear, and the medical doctors tend to act conservatively when there are differing opinions between family members. Among the available administration methods (TPN, NG tube and PEG), PEG is most convenient and advantageous in the medical fee system, in terms of management and safety [16].

The treatment method for elderly people who are unable to take in nutrients orally is divided into four patterns [17,18].

These are as follows:

- the patients are discharged to their facilities or homes to allow for the situation

- to run its natural course (oral nutrition), with a projected life expectancy within 1 month;

- the use of EN is associated with life expectancy of 12-18 months;

- the use of PPN is associated with life expectancy of 2-3 months; and

- the use of TPN is associated with life expectancy of 6-12 months; Since many elderly patients have dementia, those who cannot eat and drink orally require their family to decide the nutritional administration method

The psychological and ethical considerations associated with maintaining AHN include the mental well-being of the doctor and family, prevention of starvation and death without intervention, divergent opinions of separated families and relatives who appear at the end and argue for further life prolonging medical care and postponing the decision [19]. Additionally, highly invasive medical procedures for elderly patients with advanced frailty may cause harm without any benefit. AHN has been discussed by The Japan Geriatrics Society, The Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine, and The Japanese Association for Acute Medicine, and the 2012 ‘Position Statement’ was announced by The Japan Geriatrics Society [4]. The NST activity is thought to contribute to the introduction of AHN as a concrete option, and the further acceptance and use of NST activity is important.

Conclusion

For swallow function, the improvement rate of the patients with a Gr≤5 was 10 %-20% regardless of sex, age and pneumonia status. After the NST’s interventions, the nutritional administration methods used in the pneumonia group with a Gr≤5 were as follows.

Among male patients aged ≥80, one out of four died in the hospital, two out of five were discharged on an oral diet, and the rest required AHN, while among female patients aged ≥85, one out of six died in the hospital, three out of five were discharged on an oral diet, and the rest required AHN. When comparing male patients aged ≥80 and female patients aged ≥85 with pneumonia, a statistically significant difference in the number of discharges on an oral diet and hospital deaths was found for sex, with worse scores for males. NST activity was considered to contribute significantly to the decision to introduce AHN as a concrete option.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the elderly patients and hospital staff who cooperated with this study. This study was approved by the hospital ethics committee (approval number 27-01). For the cases in which the patient had difficulty indicating their intention, verbal consent was obtained from the family and all the patients were de-identified.

References

- Fujishima I (1998) Stroke eating and dysphagia (2ndedn). Medical, Dental and Drug Publishing, Tokyo, Japan.

- Oguchi K, Saito E, Mizuno M, Baba M (1998) Screening method for dysphagia “Repetitive saliva swallowing test” (RSST). Treatment 80: 1405-1408.

- Okui M, Baba T, Matsuo K (2001) The clinical severity classification of eating and dysphagia and its relation to revised water drinking tests and food tests. Journal of Japanese Society of Eating and Dysphagia Rehabilitation 5: 75-75.

- The Japan Geriatrics Society (2012) Guidelines on the decision-making process of aged care -Focusing on the introduction of artificial hydrate and nutrition -2012 edition. Medicine and Nursing, Chiba 6: 29-34.

- Kanda Y (2012) Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplantation 48: 452-458.

- Terada K, Muro S, Ohara T, Kudo M, Ogawa E, et al. (2010) Abnormal swallowing reflex and COPD exacerbations. Chest 137: 326-332.

- Tsuzuki A, Kagaya H, Takahashi H, Watanabe T, Shioya T, et al. (2012) Dysphagia causes exacerbations in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 60: 1580-1582.

- Kagaya H (2012) Overview, Eating and swallowing rehabilitation from acute phase to home. J Clin Rehabili 21: 834-837.

- Teramoto S, Fukuchi Y, Sasaki H, Sato K, Sekizawa K, et al. (2008) High incidence of aspiration pneumonia in community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized patients: a multicenter, prospective study in Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc 56: 577-579.

- Yamawaki M (2010) Epidemiology of aspiration pneumonia. Geriatr Med 48: 1617-1620.

- Ishida T (2011) [Epidemiology of pneumonia in Japan -- current status and future considerations]. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi 100: 3484-3489.

- Kikuchi R, Watabe N, Konno T, Mishina N, Sekizawa K, et al. (1994) High incidence of silent aspiration in elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 150: 251-253.

- Tohara H, Saitoh E, Mays KA, Kuhlemeier K, Palmer JB (2003) Three tests for predicting aspiration without videofluorography. Dysphagia 18: 126-134.

- Nishiwaki K, Tsuji T, Liu M, Hase K, Tanaka N, et al. (2005) Identification of a simple screening tool for dysphagia in patients with stroke using factor analysis of multiple dysphagia variables. J Rehabil Med 37: 247-251.

- Wu MC, Chang YC, Wang TG, Lin LC (2004) Evaluating swallowing dysfunction using a 100-ml water swallowing test. Dysphagia 19: 43-47.

- Aida K (2008) Elderly people and life-prolonging treatment. Life and Death Studies 5 (Edited by M. Takahashi and M. Ichinose). The University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo, Japan.

- Miyagishi T, Higashi T, Akaishi Y (2007) Clinical features and prognosis of terminal ill patients in a long-term care hospital with particular regard to the implications of artificial nutrition. Nippon Ronen Igakukai Zatusi 44: 219-223.

- Kosaka K, Satoh T, Fuji M (2008) Proposals for end-of-life care for the elderly. Jpn J Geriat 45: 398-340.

- Aida K (2011) Life-prolonging medicine and clinical practice. The University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo, Japan.

Citation: Niwano M, Kikuchi K (2021) A Comparative Study Evaluating Improvement of Swallowing ability of Elderly Patients who Admitted to the Internal Medicine Department with Dysphagia using Fujishima’s Dysphagia Grading System. J Gerontol Geriatr Med 7: 105.

Copyright: © 2021 Mototaka Niwano, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.