A Model of Successful Transition from Home to a Long-Term Care Community: A Grounded Theory Study

*Corresponding Author(s):

Daniel Koltz, Ph.DDepartment Of Health And Human Development, Montana State University, Montana, United States

Tel:+1 4069944351,

Email:daniel.koltz@montana.edu

Abstract

The transition process and experience for older adults who move to independent and assisted-living communities is unique to each person but a universal issue. This research focused on understanding what the predominant factors are for a successful transition to a Dependent Living Environment (DLE). A constructivist grounded theory approach was used to explore the experiences of 18 older adults who had moved to a DLE which includes independent and assisted living accommodations. The study participants ranged in age from 65-95 and were equally male and female. Equal numbers of people transitioned into both types of DLE communities. The central concept of behavioral attitude is influenced by five factors to shape a self-reported successful transition. The five factors contributing to their positive attitude are creating a new place, increased community integration, a sense of safety and security, independence while dependent and accepting a new life stage. A model of transition was co-constructed through a process that represents the meaning of a successful transition for people who experience a change and move to a DLE.

Keywords

Adaptation; Assisted living; Attitudes; Factors of success; Independent living; Successful transitions

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic continues to persist, and fear is prevalent among residents living in long-term care communities across the world. In addition to this fear, older adults would prefer to live in their own homes as they age [1]. While most people prefer to remain in their homes, some older adults need to transition to long-term care communities to get assistance for basic activities of daily living [2]. Loss of independence and fearing what a change encompasses are the biggest challenges for a successful transition [1]. Leading to an unanswered question of how an older adult can transition successfully from an independent living at a private residence to a dependent living environment (DLE)?

Across the world a population shift has occurred, and more people are at an age where needs increase which necessitates a transition to long term care communities. In the United States the National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) and AARP [3,4] are predicting that many older people will need to transition to Dependent Living Environments (DLEs) by the time they reach the age of 70; even with programs that promote aging-in-place [1]. Most people who enter board-and-care housing and assisted living are between the ages of 65 and 84. For years, the U.S. Census Bureau [5], NAC Reports [3,4], and other leading aging organizations have been discussing the expansion of our older population and how the U.S. should work to understand the effects of this on social services. These issues are the same for many other developed countries across the world, deciding how to care for aging people who need assistance with ADLs and IADLs.

To fully explore the process of a successful transition to a DLE, one must examine the differences between a change and a transition. The change incorporates not just a beginning but the ending of something. Often older adults are confronted with a change that will be permanent [6]. As we age, loss of independence is the most significant change in a person's life; therefore, we struggle to accept these changes. Transitions to a DLE can be an emotional time for an older adult to deal with such change [6]. A transition typically begins when a change in our lives is forced on us because of a significant life event. Joanna Schlossberg’s [6] transition theory explains why transitions occur. Events such as illness and disease are the most common reason for an older adult’s transition into a DLE [4]. Transition theory is used as a framework of understanding to explain why change is needed for an older adult to relocate to a DLE. The theory, however, does not explain how an individual transitions successfully and what factors were impactful in adjusting to the change. Leaving unanswered questions on the factors of a successful transition that have not been addressed in previous research on transitions conducted by Schieble et al., [7]; Scott & Mayo [8]; Sussman &Dupois [9].

Past research was conducted on the periphery of this topic [7-11]. These studies produced information on the factors of adapting to or the process of a transition to assisted living or skilled nursing. These studies were conducted in communities from around the world, indicating the issue is universal and translating similarly for older adults from differing backgrounds. Researchers have concluded that older adults who need to relocate to DLEs should be included in the decision-making process and are more likely to adapt successfully to their new environment [8,11-13]. Furthermore, social connections with staff, other residents, and administration increase the comfort of the new environment [9-11]. Resiliency is a primary factor reported by researchers that could provide a context as to why specific individuals can be socially integrated into new environments more easily [7,12]. Additionally, race, gender, and social connections appear to be other factors that impact a positive adaptation to a new living arrangement [14]. These factors provide reasonable answers for improving the lives of older adults and support the need for continued research on this topic. The primary question addressed in this research is what perceptions and experiences of an older adult's transition from independent to Dependent Living Environments (DLEs) are connected to successful/non-successful transitions? The answers to this question will help us understand the concept of transition and its connection to success, which is a new conceptual topic on the discussion of transitions.

Research Method

Qualitative research approaches are used when examining or exploring a phenomenon in depth where the variables are unknown ([15] p. 42). The purpose of conducting a qualitative constructivist grounded theory study on older adult transitions was utilized to understand the connections, actions, and processes older adults perceive as their experience while transitioning from an independent living environment to a DLE. Older adults transition differently to DLEs; some would consider their transitions successful, while others would not. We know 20% of older adults in assisted-living facilities report a successful transition to their new environment [16]. But why? A grounded theory approach attempts to identify what is not known. An inquiry asking participants directly through qualitative interviews about the how, what, where, and why they experienced transitions is a sound approach to understanding the transition and any connections to success [17].

The research questions elicited responses about processes that influence the perception of success and create a model of how the process is essential for successful transitions. Answering these questions did result in a grounded theory for identifying primary factors of success. The constructionist grounded theory method did convey an interpretative portrayal ([15,18]; p.83) of the transitional process that older adults experience when deciding to move from a family home, during the move, and after a move into a DLE [9].

Research Design

According to Creswell and Poth ([15] p.83), grounded theory utilizes a distinct step-by-step process for data collection and analysis focusing on actions and processes. The grounded theory design used for this study is from a social constructionist paradigm [18]. An inductive approach is used to answer questions about a problem to formulate a substantive theory, with the researcher being the primary instrument in data collection. Interviews and memo writing were the two primary modes of data collection for this study [15,18]. Data analysis coincides with data collection until a rich, thick description of a phenomenon produces a theoretical model as a framework of understanding. Initial, selective, axial and theoretical coding were used throughout the data collection process. The constructs or factors identified through data analysis were used to understand the connections associated with the actions and processes of a transition and ultimately formulated a theoretical model of transition success.

Study population and sample selection

DLEs are board-and-care homes, assisted-living facilities, and nursing homes that assist with ADLs. Most identified research focused on nursing home transitions after the move. Still, the populations that reside in assisted-living and board-and-care homes face life-changing transitions from family homes. Three sites were selected to examine residents’ transition experiences who had recently moved within the past year. The focus of this research was on independent and assisted living community living in early months of 2020.

Selection of participants

Purposive maximum variation sampling was used to invite participants by identifying older adults who resided in DLEs transitioning from a long-time home. The maximum variation sought in this research was how older adults view transitions as successful or non-successful. Participants with varying perspectives on the problem were invited to participate [19]. After eleven participants were interviewed, it was determined that saturation was met; however, seven additional participants were interviewed to confirm saturation, and no new threads of information or themes were identified. The total number of people who participated in the study was eighteen.

Five criteria were used to select eighteen participants for the study purposely. The first criterion is residents had relocated to a DLE within the last year. The second criterion used is participants lived in independent environments (their homes) before moving to DLEs. The third criterion is that participants are at least 65 years of age at the time of their first interview. To meet the fourth criterion, participants needed to be available for two to three interviews that lasted for as long as one hour. The fifth criterion for maximum variation was that participants must be living in either of the two stated DLEs: a board-and-care (independent living) or an assisted-living community. By following these guidelines, the research provided a rich and thick perspective on the connections, actions, and processes of transitioning successfully to DLEs.

The process of gaining access to participants for this study began by contacting executive directors from three senior-living communities. The researcher conducted all the interviews after informed consent was received from the participating residents of the study. After the organization agreed to allow the research to occur, these permissions were submitted along with an IRB application through the Concordia University - Chicago IRB approval process, in which approval for the study was granted.

Data collection and analysis process

The steps for the research process are described below to identify the data collection and analysis process and how they are linked. Phase 1 - Secure site permission and participant informed consent to participate in the study. Phase 2 - Seek and obtain IRB Approval from Concordia University - Chicago. Phase 3 - Initial Interviews (60-90 min; using constant comparative analysis); two-four participants. Phase 4 - Initial memo writing and data analysis using initial coding soon after the first interviews begin. Phase 5 - Interview the two-four participants a second time to explore more transition experiences. Phase 6 - Continue coding two-four interviews using focused coding methods. Phase 7 - Repeat Steps 3-6 with new participants (n = 8-20) until no further information is gathered. Phase 8 - Memo writing and data analysis focused coding of Participants (n = 8-20). Phase 9 - Memo writing and theoretical coding/mapping (this process could begin anytime a picture starts to develop. Phase 10 - Axial coding (e.g., matching data with research questions). Phase 11 - Third interviews are scheduled to clarify experiences and reflections on the process, actions, and meaning. Phase 12 - Formal theoretical model/mapping Phase 13 - Focus groups organized and used to help connect the theoretical themes and co-construct a final conceptual model.

One of the building blocks for grounded theory analysis is constant comparative analysis [18], created by Glasser and Strauss [19] as the means of evolving grounded theory [15]. Data analysis was a 4-step process that utilized constant comparative analysis during all the steps. Step 1 - Initial Thematic Coding. Step 2 - Focused Coding. Step 3 - Axial Coding. Step 4 - Theoretical Coding.

Demographics

Table 1 represents the demographics of this study's sample. The participants (n=18) were from all the older age groups, the 60s, 70s, 80s and 90s. They are equally represented by independent or assisted-living apartments within the two facilities used for this research. Each participant was assigned a fictitious name to keep their identity confidential.

|

Name |

Age |

Sex |

Marital Status |

DLE type |

When Moved |

Self-evaluated Success/Non-success |

|

Bob |

65 |

M |

single |

Independent |

5 months |

Yes |

|

James |

83 |

M |

married |

Asst Living |

10 months |

Yes |

|

Sam |

86 |

M |

married |

Asst Living |

10 months |

No |

|

Judy |

81 |

F |

married |

Independent |

10 months |

Yes |

|

Tracy |

83 |

F |

married |

Asst Living |

6 months |

Yes |

|

Grace |

92 |

F |

widowed |

Asst Living |

3 months |

No |

|

Sandy |

88 |

F |

widowed |

Independent |

3 months |

Yes |

|

Fred |

81 |

M |

separated |

Asst Living |

6 months |

Yes |

|

Tina |

77 |

F |

widowed |

Asst Living |

4 months |

Yes |

|

Helen |

92 |

F |

widowed |

Independent |

3 months |

Yes |

|

Eva |

91 |

F |

widowed |

Asst Living |

5 months |

Yes |

|

Janet |

68 |

F |

single |

Asst Living |

3 months |

No |

|

Mary |

72 |

F |

married |

Independent |

8 months |

Yes |

|

Tom |

75 |

M |

married |

Independent |

3 months |

Yes |

|

Hazel |

78 |

F |

widowed |

Asst Living |

4 months |

No |

|

Gloria |

81 |

F |

widowed |

Asst Living |

10 months |

Yes |

|

Mike |

83 |

M |

widowed |

Asst Living |

9 months |

Yes |

|

Tom |

88 |

M |

widowed |

Asst Living |

11 months |

Yes |

Table 1: Demographics of the population and sample criteria.

Data collection & analysis

The first four interviews individually occurred on the same day and lasted between 45-70 min. Notes in the form of memos were written after each interview. The memos were used to ask additional probing questions. These follow-up questions were related to the experiences the participants shared. The transcripts were read line by line, and the words most often spoken by the participants were related to health issues, assistance, my family, activities, and moving in. The initial codes that emerged immediately and were consistent during the process of data collection are represented in table 2. The second set of codes identified from the first four interviews were axial codes that answered who, what, where and when questions about the process. After each interview, the axial codes were charted on a memo board. Based on these thematic words, it was determined at this time in the research to ask further follow-up questions during Interviews 5 through 11.

|

Pre-Move |

During Move |

After Move |

|

Time Frame |

Time Frame |

Settling In |

|

Health Factors |

Moving Personal Items |

Engaging with Staff |

|

Assist with ADLs |

Moving In |

Engaging with Activities |

|

Role of their Family |

|

Integrating with Community |

|

Decision on Personal Items |

|

Feeling at Home |

Table 2: Initial codes after first four interviews.

The initial themes were derived by reading the transcripts word for word and line by line, and a chart was created to visualize the themes for each resident. The chart became a memo board folded up and referenced between interviews. All the interviews were read word by word and line by line to fill in data on the memo chart as each participant shared them. Interviews 5 through 10 occurred the following week over three days at the second site and one more interview from the first site for a total of 11. After each block of interviews, the transcripts were transcribed and verified for accuracy the same day.

Furthermore, each transcript was analyzed to determine if any new concepts had emerged and compared with the information provided by the first four participants. What did emerge from interviews five through eleven were concepts that connected the processes and actions that were evident to a successful transition. Focused coding of these emergent themes was written at the top of the memo chart as they were constructed with the participants during the interviews. The process of focused coding occurred between Interviews five through eleven, and the focused codes were written at the top of the memo chart, which was used for probing questions as Interviews 6 through 11 occurred. Table 3 shows the key connections between the actions and processes of a transition to provide meaning for why the move was successful. These key concepts were a component of focused coding to understand the research questions on why some individuals had successful transitions, and others did not.

|

Positive Attitude |

|

Creating “Place” in New Home |

|

Acceptance of New Life Stage |

|

Safety/Security |

|

Independence while Dependent |

|

Integrating with Community |

|

Loss/Grief of Self |

|

Loss/Grief of Stuff |

Table 3: Focused codes developed during interviews 5-11.

After the focus codes emerged from the first eleven participant interview transcripts, follow-up interviews were scheduled with seven participants to clarify the connections to a successful transition. The follow-up interviews were conducted to member-check the codes to determine if these factors reflected the participants’ perceptions and experiences of their transitions. The second interview provided substantiated details on how the connecting concepts completed the process of understanding what was key to a successful transition to a DLE. Axial coding was conducted by reading through the transcripts and reviewing the updated memo chart throughout the interview process. Axial coding provided information about who was involved in the process, provided a time frame, and connected these concepts to success/non-success.

A theoretical picture emerged early, and after the second interviews, the theoretical concept was confirmed by each of the seven participants as representative of their transition experiences. My role as the researcher and the amount of time spent in the field, which was over 80 hours, aided in determining that saturation was met at the eighth or ninth interview and, indeed, when interview eleven occurred. However, to confirm that saturation was met, participants twelve through eighteen were interviewed to verify if any new information could be extracted. Participants twelve through eighteen shared similar stories as participants one through eleven on the processes and actions they experienced while transitioning to DLEs. A focus group was convened as the third interview to review the research findings. Every common factor of a transition was discussed on how it related to the concept that developed. The focus group confirmed the theoretical model described by each person as reflective of their transition experience.

Trustworthiness

Creating trustworthiness through the process of crystallization includes all the primary aspects associated with rigor, validity, and reliability but with an understanding that construction of meaning may not be replicable [20]. For this study, I crystallized my role as the researcher in descriptions of how I view the world through a post positivist social constructivist lens. Rigor is crystallization through transparency during the research process and investigating the phenomena in depth ([15] p.273). In this study, rigor was in the form of time spent in the field, engaging with participants through interviews and analysis. I was in the field through prolonged engagement with over 60 hours in the field and conducting data analysis. Of the 60 hours, 20 or more hours were dedicated to a co-construction of my participants’ meaning of the phenomena. Validity is based on the methods used for collecting data ([15] p. 273).

Findings

The research questions answered through the inquiry are: What processes and actions perceived and experienced by older adults who move to a dependent living environment are connected to a successful/non-successful transition? Sub-questions are what actions and processes contribute to a successful/non-successful transition to a dependent living environment? How do older adults define their transition to a dependent living environment?

Processes and actions of moving to a DLE

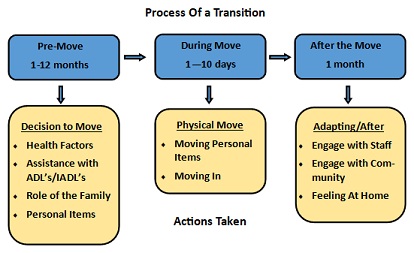

The processes and actions the participants experienced in their transitions were generally similar across all the participants in how they moved into their respective DLEs. What was difficult when reviewing the two concepts was being able to parse out the actions versus the processes because the concepts are integrated. Figure 1 portrays the integration of the two concepts.

Figure 1: Transition actions and processes.

Figure 1: Transition actions and processes.

Three distinct parts of the process were identified before the research: pre-move, during the move, after the move, and these form the framework for the process of a transition to a DLE.

Pre-Move

While there is not a clear consensus regarding how long it took participants to decide if they should move from their homes to DLEs, it is a relatively short period. The time frame that all 18 participants experienced were from one to twelve months. Individuals on the shorter end of the time frame, which consisted of one to three months, are people who needed assistance because of a health issue or had a partner with health care needs. The factors associated with a move to a DLE include health factors, assistance with ADLs, family role and decisions on personal items. One factor of the pre-move is most participants indicated they wanted to tour locations to identify if the community met their needs and to decide if they felt comfortable moving to a senior living community. Everyone expressed a sense of connection to their choice of location. Whether someone moved into independent or assisted living did not impact the time frame in which people decided to move.

Health factors: Most of the participants had experienced some health issue or were a partner of someone with a health issue. This factor was no different for independent or assisted-living accommodations. A primary factor for the transition was someone who could no longer care for their spouse or described how they needed assistance because of their health issues. In addition, they couldn’t do all the work necessary to take care of homes and details of life that once were so easy to do. Leading to a discussion about the next factor in the decision to move to a DLE, needed assistance with ADLs.

Assistance with ADLs: Many participants in this study expressed disappointment in not being able to take care of their homes, while others needed help caring for their partners’ health issues. The residents who experienced the need for assistance in managing their property could see the benefits of having these tasks done for them. Other people expressed needing help with ADLs because they had some health limitations. By relocating to a DLE, meals are provided in a common dining area, and all the apartments have stoves, but they can choose how they are prepared. Needing help with ADLs and IADLs is something that all the participants shared as part of their transition experience. It was a significant factor in deciding to move to independent or assisted-living accommodations.

Role of the family: Throughout the one to twelve-month time frame it took to decide to move to a DLE, most participants had discussions about a potential move with their families. Some people labored over the decision, not knowing what to expect from community living. While they labored over this decision, their families played a supportive role in the decision to finally make a move. The role of the family was integral to receiving the assistance necessary to live a better quality of life. The residents expressed that the decision was ultimately their own. Their family was encouraging and helped to outline what factors were helpful for them to be successful. Participants who felt pushed into the decision were less likely to have a successful transition while knowing it was in their best interest to get some help in an assisted-living community. For the successful participants, family played a central role in helping them decide to move. Ultimately no one was forced to move, even if they felt coerced. The family also played a minor role in going through what personal items were moving and which ones needed to be let go.

Decisions on personal items: Almost every participant stated that they were the person who decided what personal items were going to move with them to their new place. In most circumstances, the family was involved in receiving items or helping the older adult sell or give away the personal things they would not keep. Some people struggled with the process but not parting with personal items. The difficulties in deciding what to keep and what to get rid of were something that everyone experienced. The central factor of this experience was that all the participants had a process they had to undertake with their belongings to transition to a DLE.

During the move

The process for older adults moving from their long-time homes to independent or assisted living was the short time frame for the participants of this research. It included the physical move, the process of moving into the new place, and setting up their new living space. Most of the participants in the study moved into their new places less than a week after they had navigated the pre-move process. The only time a move lasted longer than a week was when people relocated from out of state. The time frame to move took one day, and the unpacking took less than a week to set up their new home.

The process of moving included having family physically help with the move, with very little assistance from the management or staff from the new place. Family members were the primary movers and helped their older family members set up new space. Assistance from the facility was in the form of names and numbers of moving companies and people that could assist with the physical move. Only two people discussed having some assistance with hanging a picture or two from maintenance.

Moving personal items: Family played an instrumental role in physically relocating all the individuals in the study to their new places. Every participant had a family member help them relocate, so they did not have to hire anyone. Additionally, most of the study participants described how they had an active role in helping with packing things up and helping to load lighter belongings onto trucks. However, most of the heavy lifting was left to the family to assist their loved one. The study participants were able to participate minimally with smaller items. Still, they could watch family move their personal belongings because they could no longer do the heavy lifting. The family also played a significant role in getting them into their new place.

Moving in: When they arrived at their new places, family members carried everything in and helped them set up their new places immediately to help them feel at home. They could direct where their items should be placed, whether in the kitchen, their bedroom, or their living space. It was essential to set up their new places as soon as they arrived and begin the process of creating their new spaces. The concept of moving in was a physical action and central theme at the beginning of the data collection. However, this aspect of the process was later developed in answering the research question on connections to a successful transition.

After the move

After the move to DLEs, older adults experienced a process similar to settling into the new environment. The process of settling into their new home varied across participants but included engaging with staff, engaging with activities, integrating with the communities, and feeling at home.

Engaging with staff: One of the significant concepts identified in the research was staff play a major role in helping the residents adapt to their new homes. Executive directors, office staff, caregivers, and activity directors all play an essential role in a person's adapting to the DLE. A friendly staff member who knows their name help with adapting to the new living environment.

Engaging with activities: Activities provided for both residents living in independent and assisted-living accommodations are a vital aspect of the transition process. Most study participants expressed the importance of activities in their transition experience. Activity plays an integral role in the process of adapting to a transition to a new place. It works together with the next concept of integrating with their new communities. Meeting people is important for having someone to eat meals with and interact socially.

Integrating with community: Most of the participants in the study expressed how they used activities and the community meal dining hall to interact with other people. They told this in terms of being invited to meals and other groups they had formed as they met people. These interactions helped them to feel comfortable and adapt to the DLE.

Feeling at home: During the interviews, each participant was asked about feeling at home. Every participant who expressed having a positive transition experience shared that they felt at home right away because of the staff, the people they were getting to know, and by setting up their new places. The concepts of each part of the transition have created a picture of the experience that answered the research questions on the processes and actions of a successful transition.

Successful/Non-successful transitions

The next component of this research emphasized the older adult's perceived experiences of a successful transition. Participants were asked whether they felt their transition to their new DLE was successful. Of the eighteen participants interviewed, fourteen viewed their transition processes as successful, while four did not. Of the first eleven participants, nine expressed that they felt their transitions were successful, while two did not perceive they were successful. The perceived experience of the processes and actions involved in moving to a DLE was similar for both successful/non-successful participants, as described in the previous section of this research. The first two participants who self-reported an experience that was not successful also shared their reluctance to move to the DLE. When asked if they felt pressured by their families, they would not implicate their children. They both were reluctant to say they were forced to move into the DLE, but they had not engaged with the staff or activities or begun the process of integrating with their communities. Both individuals expressed some resentment for having to relocate to their new homes. While those who reported success felt their move was good for them and the community met their needs. Participants who moved to independent housing accommodations did not answer the questions differently than those living in assisted living. The non-successful participants were identified as one in each research location, and their experiences of the processes and actions were the same as those of successful people; however, their attitudes and responses were connected differently and are explained in detail in the next section.

Connections between processes & actions and success

The connections contributing to a successful transition emerged shortly after the fourth interview and were refined during Interviews 5 through 11. The second round of interviews served as a member check and included follow-up questions about the connections from the processes and linking them to success. One overriding concept emerged for why people self-reported successful transitions: behavioral attitude. The concept of having a positive attitude about life and circumstances around change was the same for every person. Additionally, the emergence of five direct connections was identified to explain what a successful transition is. They include accepting a new life stage, creating a new place (space), independence while dependent, a sense of safety and security, and community integration. All five concepts are connected to having a positive attitude and are linked to the processes of a transition to success. Figure 2 depicts this process and how the connections are linked through participants’ positive attitudes to help them conclude they have had positive and successful transitions to DLEs.

Figure 2: Connections to success.

Figure 2: Connections to success.

Positive attitude

The process that each individual experienced and the actions they took revolved around their positive attitudes toward life. When interviewing each person, they shared factors that reflected their positive attitudes. The self-reported successful participants were asked follow-up questions regarding their positive experiences, and all indicated they always had positive attitudes. They encountered many things in life, but positivity carried them through difficult situations. Their positive attitudes enhanced their ability to experience the five connecting concepts that increased their positive feeling about their transitions, which contributed to experiencing a more successful transition for them individually. The individuals who did not experience successful transitions expressed that they did not believe they had a positive attitude about their life experience at the time. All the opposite characteristics related to five factors were identified in individuals with negative transitions. Self-reported non-successful older adults concurred that identified factors of a transition were accurate for themselves. The main concept is that a positive attitude is central to connecting the meaning of the process of a transition to a successful experience as they transitioned to a DLE.

Creating a new place (Space)

During the process of the move to a DLE, the participants shared their experiences of the actions they took to move. After they arrived at their new home, every participant had family members assist them in setting up their new place. The meaning behind moving to a new apartment was the creation of a place they could call home. The participants expressed how they felt at home quickly when they unpacked their belongings and set up their new places. As one person stated, “I had my daughter hang up my pictures to make it feel like home.” They felt that hanging up things on the wall and having familiar furniture set up helped them feel they were moving in and could be happy there. A positive attitude influenced their decision to accept their new space as a home. Multiple factors helped shape the connection to their new home, including the staff at the new place, having their belongings, having time to move in the way they wanted, feeling accepted and having family near them. What did emerge as part of creating a new space was the role of the staff. The DLE staff played a pivotal role in connecting with the residents individually. The staff improved success by complimenting the participants’ choice of new places in their centers and knowing their names. The self-reported non-successful participants shared how they did not set up their space; one reported, “I hope to go back home someday. I have not even sold my house yet.” The older adults who experienced this knew they needed help with ADLs and were holding out hope to leave someday. Their attitude regarding the move is negative, and they do not see a way to move past this thought. Leading to the next factor that plays a role in success in accepting their current life stage.

Accepting a new life stage

The concept of accepting the stage of life that you are in was prevalent in the responses from participants. It is connected to each participant’s experience of why they chose to move into a DLE rather than age in place in their long-time home. For the participants who self-reported non-successful transitions, they had not entirely accepted the stage of life they were in and would instead have moved back to their long-time homes. While this was their experience, they also understood it was necessary to get more help for themselves and a partner. One person stated, “my wife needs help with everything, and I cannot help her.” Another person said, “I cannot even climb the stairs anymore at my condo.” Both of these older adults shared how they have not accepted the need for help and look forward to returning to their homes.

Self-reported successful participants expressed that they had accepted their new residence as somewhere they could be happy. Each successful study participant had a positive attitude and articulated responses representing that type of behavior. One person said, “I accept that I need help with cooking and my medications and feel this is the best place for me at this time in my life.” Another said, “I decided I didn't want to cut the lawn and paint the trim anymore, my knees can’t take it, so it was time to make my life easier at my age.” In addition to needed help, it was found that transitioning successfully is connected to the acceptance of their new life stage and having a positive attitude by connecting with their new community and having family support nearby. The connection between accepting a new life stage to the success of a transition to a DLE is a concept that is interrelated with having a positive attitude.

Independence while dependent

As articulated by the study participants, they all described how they could choose to do whatever they wanted even though they used services provided by the DLEs. “I can leave when I want, I can eat when I want, and I can even go to a family’s house for a few days if I want.” “The self-described non-successful participants shared how they felt they had some independence but felt they were told what to do most of the time.” An example provided was, "I have to sign out, so they know where I am at all times, I am not a free person.” When the discussion continued, the older adult did say they could drive anywhere they wanted, it was just something they had to do. These two perceptions were in complete contradiction to each other. The connection between having a positive attitude and a positive outlook on their transition allowed them to decide they could make independent decisions about their life moving forward in a DLE.

In the DLE, residents’ negative perspectives spoke to the issue of unfettered access to their apartments, but the people gaining access were caregivers, cleaning staff, and the administration. Nobody else complained about unfettered access to their rooms because they stated: “staff did knock on their doors before entering.” Most participants could drive, and generally, those in assisted living utilized the bus service that they could schedule anytime they wanted. The participants acknowledged some level of dependence because they used the services provided for their safety and security. A positive attitude allowed them to experience more independence and see the positive reasons for living in a DLE.

Community integration

The available activities and the shared dining services provided in a DLE encourage everyone to integrate into the community. ”I love the activities they have here, and we had wine and cheese social hour the other night.” “I love that I don't have to cook, and I always have someone to eat with.” The context of integrating with the community comes from a variety of sources. The study participants expressed how the facility staff being personal with them helped them feel welcome. Additionally, having a positive attitude influenced their decisions to engage in planned activities and meet new people. Mealtime was also a time to meet new people.

When new residents have difficulty integrating into the new DLE community, they are often less successful. “I don't sit with anyone when I eat, and I certainly don’t want to engage in bingo” is what one person with a negative perspective shared. This concept generally has to do with the individual’s attitude. It may prohibit them from concluding their transition is successful because they did not put in the effort to integrate with the community. When the participants expressed optimism about dining with others or participating in activities and having a social experience, they were more successful. It allowed them to get more fully integrated into the community, which leads to a sense of safety and security that allows for each person's sense of security.

Sense of safety/security

The primary reason for moving into a DLE is related to health factors and the need for assistance with ADLs and IADLs. Every participant in this study expressed their sense of safety and security from being in a DLE. The participants who self-reported non-successful transitions admitted they needed assistance and did not have the same sense of safety and security as those who reported successful transitions. One person said, “they are always vacuuming, and the cords are there, and I could trip and fall.” Another person said, “they salt the sidewalks so much in winter, and I almost fall because of the salt.” These individuals attempted to identify some concerns, but when asked to describe the benefits, they would also express that they don't have to worry about themselves and are taken care of. The older adults with positive attitudes toward their transition shared, “I feel safe here because if I fall, someone is always nearby to help me.” I know that I don't have to worry about being out there by myself, and nobody here will hurt me.” Those were common phrases heard during the interviews. Older adults feel safe and secure in their apartments and the community. The study participants were connected to success through a sense of safety and security at their DLEs and understood that life in the community is better for them.

Discussion and Conclusion

The connections described by the participants with the actions and processes they experienced were impacted by the behavioral attitudes they exhibited. The answer to the research questions formulated a grounded theory on this phenomenon (Figure 2). When participants had positive attitudes, they experienced positive transitions by accepting their new life stage, creating a new place to reside in, acknowledging they still had independence while being dependent, could fully integrate into the community, and could see the benefits of safety and security of their new homes. The connections, from an experience to successful transitions, provide valuable information in forming a model to help understand a DLE transition process.

Equally essential to confirm these connections to the experience were the perceptions of the self-reported non-successful participants. For almost every key concept, non-successful participants were on the inverse side of the self-reported successful participants. These experiences are equally important in explaining the theoretical construct of what it will take to improve success rates through the process theory model that was constructed. When a person who has a negative attitude toward a transition, education on the benefits of moving can be used to influence behavior. Connecting an individual to at least one could go a long way in changing the attitude toward a more successful transition. In Schieble et al., [7]; Scott & Mayo [8]; Sussman &Dupois, [9] they all identified these same factors for adapting to LTC. However, what makes this research different is the direct connection to success. None of the other studies settled on the concept of behavioral attitude as influenced by the 5 factors identified here. Connecting older adults in these circumstances to one of the essential factors improves the likelihood of success, or at a minimum, giving them a more positive outlook on their time remaining in a DLE.

A successful transition is influenced by perceived behavioral attitudes about the stage of life and the new DLEs that older adults are moving to. The connections that emerged from the research can improve success with improved staff training, family education, and education for older adults going through this same experience. Transition Theory and Life Course Theory [21] help us understand why people need to make transitions and why people behave the way they do from their historical backgrounds. People who transition need help with ADLs and IADLs, and accepting this life stage is beneficial to promote a positive attitude toward the experience. Life course theory tells us that previous life experiences and transitions shape people's attitudes [21]. When an older adult has a negative perspective about the transition and does not attempt to integrate into their new community, they are not likely to succeed in improving life for their remaining days.

Attitudes and intentions of a successful transition can also be explained by the concept of the Theory of Planned Behavior [22], which focuses on an individual’s attitude and perceived control of their situation. In most circumstances, older adults do not have volitional control regarding their own needs. They often cannot care for themselves, much less for their homes and surroundings. It is forcing them into an unwanted transition. Education around the needs that older adults may have as they age is essential to impact their behavioral attitude as they transition positively. Building education around the five success factors to improve the behavioral attitude enhances the potential to modify behavioral attitudes around a transition. Education about acknowledging their life stage, the benefits of safety and security, remaining independent while dependent, the benefits of social and community engagement, and creating their new home and space can improve attitudes. In this study, most participants acknowledged that each was a factor that influenced their positive attitude about their transition experience. Impacting one aspect may influence the attitude regarding all the other factors.

What is not known about these factors leads to how further research should be designed to parse out how each factor relates to attitude and success. Further research should test each factor on this relationship to success and if there is a particular order in which they should be addressed. I recommend that administrators of independent and assisted living communities utilize this information when bringing new residents into their community. Behavioral attitude is in individual based experience born out of our lived experience, but it is a universal issue that bridges people across the world. What is known, is that a positive attitude that reflects these five concepts can provide a pathway to a successful transition in their long-term care community. Reinforcing this concept with people with a positive attitude and working to identify which of these factors are not being met for those who come in with a negative attitude about the move. Lastly, families often discuss a transition with older parents and grandparents. They can use this information to influence decision-making and attitudes about moving to a DLE as they need one. While it is understood that changing behavioral attitude is difficult, these processes can utilize the factors outlined in this new model of understanding on how successful transitions occur.

Funding Details

There are no funding sources connected to this manuscript.

References

- Ahn M, Kang J, Kwon HJ (2020) The concept of aging in place as intention. Gerontologist 60: 50-59.

- Johnson JH, Appold SJ (2017) U.S. older adults: Demographics, living arrangements, and barriers to aging in place. Kenan Institute White Paper.

- National Alliance for Caregiving (2015) Caregiving in the United States 2015. National Alliance for Caregiving, USA.

- National Alliance for Caregiving (2020) Caregiving in the United States 2020. National Alliance for Caregiving, USA.

- S. Census Bureau (2018) Older People Projected to Outnumber Children for First Time in U.S. History. U.S. Census Bureau, Maryland, USA.

- Schlossberg NK (2011) The challenge of change: The transition model and its applications. Journal of Employment Counseling 48: 159-162.

- Scheibl F, Fleming J, Buck J, Barclay S, Brayne C, et al. (2019) The experience of transitions in care in very old age: Implications for general practice. Fam Pract 36: 778-784.

- Scott JM, Mayo AM (2019) Adjusting to the transition into assisted living: Opportunities for nurse practitioners. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 31: 583-590.

- Sussman T, Dupuis S (2014) Supporting residents moving into long-term care: multiple layers shape residents' experiences. J Gerontol Soc Work 57: 438-459.

- Brandburg GL, Symes L, Mastel-Smith B, Hersch G, Walsh T (2012) Resident strategies for making a life in a nursing home: A qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 69: 862-874.

- Brownie S, Horstmanshof L, Garbutt R (2014) Factors that impact residents’ transition and psychological adjustment to long-term aged care: A systematic literature review. Int J Nurs Stud 51: 1654-1666.

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Whittington FJ, King SV (2009) Pathways to assisted living: The influence of race and class. J Appl Gerontol 28: 81-108.

- Horstmanshof L, Garbutt R, Brownie S (2019) Older adults who move to independent living units: A regional Australian study. Australian Journal of Psychology 72: 42-49.

- Hutchinson S, Hersch G, Davidson HA, Chu AY, Mastel-Smith B (2011) Voices of elders: Culture and person factors of residents admitted to long-term care facilities. J Transcult Nurs 22: 397-404.

- Creswell JW, Poth CN (2018) Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (4thedn). Sage Publications, California, USA.

- Kozar-Westman M, Troutman-Jordan M, Nies MA (2013) Successful aging among assisted living community older adults. J Nurs Scholarsh 45: 238-246.

- Charmaz K (2008) Constructionism, and the grounded theory method. In: Holstein JA, Gubrium JF (eds.). Handbook of constructionist research. The Guilford Press, New York, USA.

- Charmaz K (2012) Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications, California, USA.

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL (1967) Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine, USA.

- Stewart H, Gapp R, Harwood I (2017) Exploring the Alchemy of Qualitative Management Research: Seeking Trustworthiness, Credibility and Rigor Through Crystallization. The Qualitative Report 22: 1-19.

- Elder G (1995) The life course paradigm: Social change and individual development. In: Moen P, Elder GH, Luecher K (eds.). Examining Lives in Context:: Perspectives on the Ecology of Human Development. American Psychological Association, Massachusetts, USA.

- Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes 50: 179-211.

Copyright: © 2023 Daniel Koltz, Ph.D, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.