A Near Fatal Ceftriaxone-Induced Hemolytic Anemia in Pediatric Age: Case Report

*Corresponding Author(s):

Sofia Brandão MirandaPaediatric Department, Hospital De Braga, Braga, Portugal

Tel:+351 926702396,

Email:asofiabmiranda@gmail.com

Joana Vilaça

Paediatric Department, Hospital De Braga, Braga, Portugal

Tel:+351 916566764,

Email:joana.gvilaca@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction

CIIHA is a rare adverse effect of ceftriaxone, occurring in about 0.1% of cases. It typically has an abrupt onset and can range from mild anemia to severe hemolytic crisis requiring intensive care. It is more common in children and can occur after the first or subsequent administrations of the drug.

Case Report

We present a case of severe, delayed CIIHA with a good outcome in a previously healthy adolescent girl without prior exposure to ceftriaxone.

Discussion and Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of recognizing and managing CIIHA promptly to achieve a favorable outcome. It is crucial to consider CIIHA in the differential diagnosis of hemolytic anemia in pediatric patients receiving ceftriaxone and to have a high degree of suspicion in cases of unexplained hemolysis.

Keywords

Case report, Ceftriaxone; Hemolytic anemia; Hemolysis; Pediatric patient.

List of non-standard abbreviations

CIIHA - Ceftriaxone-induced immune hemolytic anemia

pCO2 - partial pressure of carbon dioxide

Key messages

Ceftriaxone is a drug widely used in pediatric patients. The most common side effects include allergic reaction, gastrointestinal tract reactions, hepatic and renal toxicity. We present the case of an extremely rare but potentially fatal side effect and the importance of early recognition and proper management.

Introduction

Ceftriaxone is a third-generation cephalosporin widely used in pediatric patients that has several advantages such as broad-spectrum activity, increased efficacy, long half-life, single daily dose schedule, and reduced side effects [1,2].

Ceftriaxone-Induced Immune Hemolytic Anemia (CIIHA) is a rare but potentially fatal complication of this therapy [3,4]. It is more common in pediatric patients, and its clinical presentation typically occurs with abrupt symptoms of hemolysis [5]. The onset can vary from minutes to days after initiating treatment [6].

We report a case of severe, delayed CIIHA with a good outcome in a previously healthy girl without prior exposure to this drug. We also present a brief review of the literature to highlight its features and potential severity.

Case Report

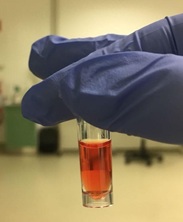

We report a case of a 12-year-old female adolescent with no relevant medical history, except for recurrent pneumonia treated in outpatient care, who was admitted to the emergency department with persistent fever and cough after three days of treatment with oral amoxicillin-clavulanic acid for suspected bacterial pneumonia. Laboratory tests showed a C-reactive protein of 107 mg/L, leukocytes at 6500/uL, and hemoglobin at 13 g/dL. Chest radiography and ultrasound revealed left lower lobe pulmonary consolidation and a pleural effusion. She was started on intravenous ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg/day and azithromycin 10 mg/kg/day. IgM mycoplasma pneumoniae, microbiology of sputum, and blood culture were negative. During the first five days of hospitalization, she had a favorable clinical course with sustained apyrexia since day two, without signs of respiratory distress and no need for supplemental oxygen therapy. After the sixth administration of ceftriaxone, the patient developed severe low back pain, intense headache, and non-bloody vomit. Physical examination revealed confusion, pallor, and progressive hemodynamic deterioration with tachypnea, tachycardia, non-measurable capillary filling time, filiform central pulses, and hypotension and rapidly progressive depressed consciousness. Acid-base balance showed severe metabolic acidosis (pH 6.88, bicarbonates 6 mmol/L, base excess -27 mmol/L, pCO2 18.1 mmHg, and lactates 16.23 mmol/L) and hemoglobin of 1.7 g/dL (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Macroscopic aspect of blood sample.

Figure 1: Macroscopic aspect of blood sample.

Ceftriaxone was suspended, and the patient received fluid resuscitation, red blood cell concentrate transfusions, fresh frozen plasma, three boluses of sodium bicarbonate and 200 mg of hydrocortisone. Continuous infusion of 15 mcg/kg/min of dopamine and 0.1 mcg/kg/min of adrenaline were initiated. There was no obvious clinical or radiological source (computed tomography scan of the abdomen, chest and brain) of acute bleeding. Blood analysis confirmed severe anemia, haptoglobin Coombs' test grade 12, which favored the diagnosis of hemolytic anemia. With these treatments, the patient's vital signs improved, and hemodynamic support was progressively reduced.

After 24 hours, the patient was clinically stable, with hemoglobin 8.7 g/dL, leukocytes 23880/uL with 85% neutrophils and 11% of lymphocytes, and C-reactive protein 9.5 mg/dL.

She completed 14 days of antibiotic therapy with vancomycin and levofloxacin and continued to taper off steroids. During the hospitalization, she had an immuno-allergology consultation that revealed an absolute contraindication for re-exposure to beta-lactams. She showed gradual improvement in her general condition, and at the time of discharge, she was in good general condition without any signs or symptoms of hemolysis.

The patient's follow-up was uneventful and there was no recurrence of hemolysis. After a period of four years, the patient remained asymptomatic and her laboratory tests were within normal limits: hemoglobin 12 g/dL, hematocrit 35.8%, mean globular volume 89.3 fl and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration 33.5 g/dL.

Discussion and Conclusion

Ceftriaxone is a widely used antibiotic in hospitalized children due to its many advantages, such as its broad spectrum activity, high efficacy, long half-life, single daily dose, and reduced side effects [3,5]. However, physicians should be aware of its potential adverse effects, including allergic reactions, gastrointestinal tract reactions, hepatic and renal toxicity [5,6]. Rare (<0.1%), but potentially fatal complications, such as drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia, can also occur [3,5].

About 20% of drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia cases occurring in children have been attributed to ceftriaxone due to its increasing use [5,7], especially in those who previously received the drug [3,5]. In approximately one-third of reported cases, a brief and self-limited hemolytic episode during an earlier dose of ceftriaxone was observed and can alert physicians to the diagnosis [3]. The majority of patients with CIIHA (70%) present underlying conditions, with sickle cell disease, HIV infection and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency being the most common [5,6,8].

The sudden onset of hemolytic symptoms made the diagnosis difficult at an early stage. The clinical presentation is typically abrupt, with symptoms such as sudden pallor, tachypnea, dyspnea, vomiting, headache, altered mental status, and lumbar or abdominal pain. In serious cases, severe anemia can lead to hypovolemic shock and cardiorespiratory arrest. Common features include decreasing hemoglobin levels, low haptoglobin levels, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, new-onset hemoglobinuria, acute renal failure, a positive direct antiglobulin test, anti-ceftriaxone antibodies, and a peripheral blood smear consistent with hemolysis, as well as a positive Coombs' test [3,5].

Treatment of patients with CIIHA can be challenging, but as in the case presented, recognizing and treating hemolysis can lead to successful management [3,5]. The usual treatment involves discontinuing the drug, providing cardiopulmonary support, and administering blood transfusions, which was the approach taken in this case [5]. Plasma exchange has also been suggested as a potentially helpful intervention. There is no evidence that steroids are effective in treating hemolytic anemia with drug-dependent antibodies, but in this case, it was a therapeutic option. Intravenous immunoglobulin may be considered in clinically emergent or refractory cases [3,5].

Studies have reported that hematologic recovery commonly occurs within two weeks. The direct antiglobulin test can remain positive for weeks or months [5]. Given its rarity and the potential for underdiagnosis, it is difficult to estimate the true incidence of CIIHA [3]. CIIHA has a high rate of organ failure and a mortality rate of at least 30%, and children tend to present with a more severe clinical course and worse prognosis than adults [9].

In conclusion, CIIHA is a rare but potentially life-threatening adverse effect of ceftriaxone, especially in pediatric patients. It is essential for healthcare professionals to be aware of this complication and to consider it in the differential diagnosis of hemolytic anemia in patients receiving ceftriaxone. Early recognition and suspension of the drug is crucial for preventing further hemolysis and initiating appropriate treatment.

In this case report, we present a 12-year-old healthy girl with a rare and potentially near fatal adverse reaction to ceftriaxone. Timely recognition and management allowed a good outcome with the survival of the patient.

References

- Finch RG, Greenwood D, Whitley RJ, Norrby SR (2010) Antibiotic and Chemotherapy. 170-199.

- Arndt PA, Leger RM, Garratty G (2012) Serologic characteristics of ceftriaxone antibodies in 25 patients with drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia. Transfusion 52: 602-612.

- Neuman G, Boodhan S, Wurman I, Koren G, Bitnun A, et al. (2014) Ceftriaxone-Induced Immune Hemolytic Anemia. Ann Pharmacother 48: 1594-604.

- Lu J, Li Q, Li X, Li Z (2018) Fatal Case Report of Ceftriaxone-induced Hemolytic Anemia and Literature Review in Pediatrics. Int J Pharmacol 14: 896-900.

- Vehapoglu A, Göknar N, Tuna R, Çakir FB (2016) Ceftriaxone-induced hemolytic anemia in a child successfully managed with intravenous immunoglobulin. Turk J Pediatr 58: 216-219.

- Boto ML, Sandes AR, Brites A, Silva S, Stone R (2011) Severe immune haemolytic anaemia due to ceftriaxone in a patient with congenital nephrotic syndrome. Acta Paediatr 100: e191-193.

- Guleria VS, Sharma N, Amitabh S, Nair V (2013) Ceftriaxone-induced hemolysis. Indian J Pharmacol 45: 530-531.

- Northrop MS, Agarwal HS (2015) Ceftriaxone-induced hemolytic anemia: Case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 37: e63-66.

- Leicht HB, Weinig E, Mayer B, Viebahn J, Geier A, et al. (2018) Ceftriaxone-induced hemolytic anemia with severe renal failure: A case report and review of literature. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol.

Citation: Miranda SB, Vilaça J, Nogueira MJ, Pontes T, Garcez C, et al. (2022) A near fatal ceftriaxone-Induced Hemolytic Anemia in pediatric age: Case Report. J Neonatol Clin Pediatr 9: 101.

Copyright: © 2022 Sofia Brandão Miranda, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.