A Reliable Mobility Assessment Tool for Multidisciplinary Use

*Corresponding Author(s):

Aamir SiddiquiDepartment Of Surgery, Division Of Plastics And Reconstructive Surgery, Henry Ford Hospital, 2799 W Grand Blvd, Detroit, MI 48202, United States

Tel:+1 3139162683,

Fax:+1 3139161155

Email:ASIDDIQ1@hfhs.org

Abstract

Objective

Study the reliability of an early mobility scale developed for use by bedside caregivers. The scale was designed to be used by both physical therapists and non-therapists. The design includes linked interventions.

Design

Blinded simultaneous evaluations by 2 independent evaluators were performed on individuals in the intensive care unit and general practice unit.

Setting

Acute care hospital.

Patients

Intensive care unit and general practice unit.

Interventions

Blinded evaluation of patients using a novel 5-point mobility scale during hospitalization.

Main outcome measures

Reliability of the new mobility scale using Kappa statistic to determine amount of agreement between 2 independent evaluators. The study was designed to have 90% power to detect a difference between Kappa statistics of 0.30 with a two-sided 0.05 alpha level test.

Main results

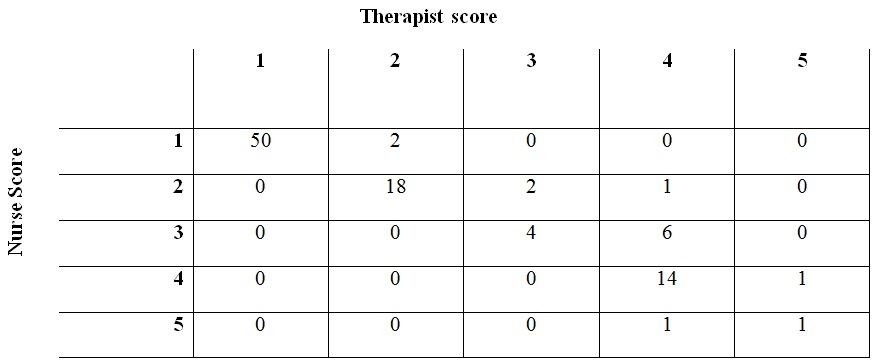

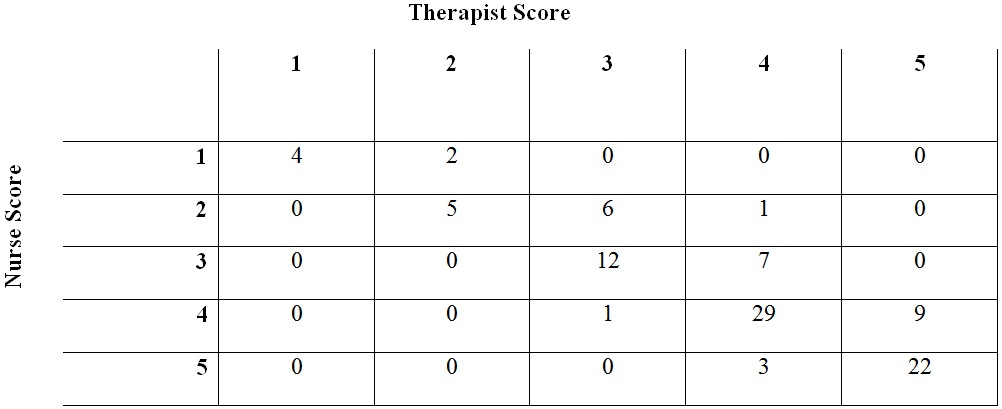

The Kappa rates of 78% and 62% in the intensive care unit and general practice unit respectively confirm inter-evaluator reliability in each setting (p-value < 0.001).

Conclusion

Our results confirm that this 5 point mobility scale can be used successfully and consistently to describe safe levels at which to begin mobility for patients in the acute care setting.

INTRODUCTION

Patient mobility in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) has received much attention. In addition to achieving better patient care, there are publically reported quality measures and reimbursement consequences to prolonged hospital stay. A focused program of therapy for stable patients in the ICU can be both safe and effective. Reversing the impact of deconditioning early in the hospital stay can positively impact hospital acquired conditions, duration of hospital stay and readmission [1,2]. For stable patients, even ventilated patients, one can develop interventions that reverse the muscle mass loss, improve orthostatic tolerance, accelerate ventilator weaning and positively impact delirium [3]. Many of these programs are specifically designs for assessment and implementation by a physical therapist. There is concern that for cost and manpower reasons staffing an ICU with therapist may be difficult. A program that does not rely entirely on physical therapist may be useful in some institutions. The purpose of our study was to develop a reliable mobility scale applicable to both therapists and nursing staff.

Our institution developed a patient mobility-focused pilot program for the medical ICU. The program is based on a 5-point mobility scale developed conjointly by physical therapists, nurses and physicians. Rather than perform a comprehensive evaluation on all patients, the scale allows one to safely and expediently determine a patients’ highest level of activity. The mobility scale has been used successfully for over 3 years in our institution. Each level has a corresponding plan of care (interventions) that can be performed with the patient. After assignment of a mobility level, the suggested interventions related to mobility, activities of daily living and exercise are carried out. This allows the caregiver an opportunity to provide up to 30 different interventions from repositioning to ambulating ventilator-dependent patients (Table 1).

| Mobility Level 1: Lying or Bedrest | |

|

Patient characteristics: *Hemodynamically unstable, obtunded or not interactive, chronically bedbound prior to admission. |

|

| Recommended Mobility and Positioning | Recommended Exercise and ADLs |

|

Reposition every 2 hours or more |

Assist with Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) |

| Mobility Level 2: Dangle or Sit at Edge of Bed | |

|

Patient characteristics: Unable to bear weight on legs. Ventilated or unventilated patient who is awake and interactive. |

|

| Recommended Mobility and Positioning | Recommended Exercise and ADLs |

|

Sit on edge of bed/dangle feet on floor Continue interventions for mobility level 1 when in bed |

Continue interventions for mobility level 1 Participate in bathing upper body |

| Mobility Level 3: STAND → CHAIR | |

|

Patient characteristics: Ventilated or unventilated patient who is able to bear weight on legs for partial stand with assist. |

|

| Recommended Mobility and Positioning | Recommended Exercise and ADLs |

|

Assist to chair, not to exceed 2 hours for each event |

Participate in bathing at seated level |

| Mobility Level 4: Walk With Assistance | |

|

Patient characteristics: Balance impairment, staff assistance required for safety or first attempt at walking during hospitalization. |

|

| Recommended Mobility and Positioning | Recommended Exercise and ADLs |

|

Use assistive device if indicated Continue interventions for mobility level 3 when up in chair |

Assist to bathroom for independent hygiene and ADLs |

| Mobility Level 5: Walk Independently | |

|

Patient characteristics: Patient demonstrates a steady gait with or without assistive devices and is able to manage equipment independently. Daily Goal: Up in chair for all meals and walk 3 or more times per day. Continue exercises. |

|

| Recommended Mobility and Positioning | Recommended Exercise and ADLs |

|

Ambulate independently Encourage patient to stay active, but ambulate safely |

Independent ADLs |

Table 1: Mobility Scale and Protocol.

Institutional data confirms statistically significant improvement in clinical outcomes with the use of this scale in conjunction with an early mobility initiative (manuscript in preparation). Mobility scale reliability is an important factor for expansion and sustainability of an institution’s mobility initiative. The aim of the present study was to examine the reliability of our 5-point mobility scale among ICU and General Practice Unit (GPU) patients.

METHODS

The examiner explained the purpose and process of the evaluation to the patient and answered questions. Examinations took 20-30 minutes. The examiner questioned the patients regarding pre-hospitalization level of activity, recent changes including surgery, procedures and pain. Starting with level 1 patient was asked to perform increasing level of activity. If the patient had difficulties with a specific activity, the examiner would repeat it. If the patient still did not perform the action properly, the examiner had the option to modify the activity or do different activity at the same level. Once the examiner felt confident that the highest level had been achieved and further testing would not change the level, he or she would stop the examination. The 2 independent observers identified a mobility level of each patient based on the information provided by the bedside nurse and activities the patient demonstrated during the examination. Each independent observer seated separately recorded the mobility level on a patient census sheet. No discussion of the levels took place. Each sheet was de-identified then individually sealed in an envelope. The results were opened and tallied by an independent blinded research assistant. One hundred ICU patients and 100 GPU patients were included in the study for a total of 200. Institutional review board guidelines were followed.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Each Kappa had its 95% confidence interval estimated as well. Landis and Koch [5] have characterized different ranges of Kappa with respect to the degree of agreement they suggest. A value greater than 0.80 may be taken to represent near perfect agreement beyond chance, from 0.61 to 0.80 substantial agreement beyond chance, from 0.41 to 0.60 moderate agreement beyond chance, from 0.21 to 0.40 fair agreement beyond chance and 0 to 0.20 slight agreement beyond chance [6].

RESULTS

| Variable | Values | MICU1 | GPU2 |

| Sex | Female | 40% | 47% |

| Male | 60% | 53% | |

| Race | Black | 52% | 55% |

| White | 45% | 40% | |

| Other* | 3% | 5% | |

| Age | 18 - 25 | 8% | 3% |

| 26 - 64 | 51% | 53% | |

| 65+ | 41% | 44% | |

| Insurance | Medicare/Medicaid | 61% | 65% |

| Uninsured | 29% | 21% | |

| Private/Other** | 10% | 14% |

2General practice unit

*Other included Hispanic or Latino, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, Asian, and 2 or more races.

**Insurance - Tricare, Veteran Affairs Health System, or insurance information was not available.

***None of the statistical comparisons between 2011 and 2013 were statically significant p<0.05.

| Location | N | Kappa ± SE | 95% CI | p-value |

| Intensive care unit | 100 | 0.779 ± 0.052 | (0.678, 0.881) | 0.001 |

| General practice unit | 100 | 0.619 ± 0.061 | (0.499, 0.738) | 0.001 |

A test of the 2 estimates of Kappa indicated that results from the ICU and the 620 were not significantly different with p-value > 0.10. Additionally, the 2 populations were similar without evidence of statistically significant differences (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Our results confirm that this 5-point mobility scale can be used successfully and consistently to describe safe levels at which to begin mobility for patients in the acute care setting. Using this scale, we have identified a reliable starting point for early mobility. The descriptors and outlines for the levels (Table 1) were designed for nurses and other bedside caregivers rather than only therapist. This may separate our mobility program from others. Historically this scale was used by the therapist to mobilize patients after orthopedic surgery. Over time it was adapted by the nursing staff to communicate among themselves and as part of the hand off process. We chose this scale because there was already buy in from our allied health professionals and a track record > 5 years of safety.

The literature confirms that early mobility programs improve patient outcomes [1-3,7]. Pashikanti and von Ah identified that the greatest impact on successful early mobility is through standardized mobility programs and protocols. Most early mobility programs appear to be very focused around the skill sets of the therapist. Costs, sustainability, and wider acceptance of early mobility bundles may come from nurses and other bedside caregivers (not only rehabilitation therapists) becoming stakeholders in this endeavor. Our mobility scale was developed with this in mind. The daily working language of caregivers is different for different disciplines [8]. For therapist there is an increased emphasis on global patient level of function, deconditioning and long term care planning. For many unit-based caregivers, mobility is a finite issue. What can this patient do safely, today in the unit. Our goal was a survey tool linked with specific activities that should be reproducible and transferrable to any acute care unit. We used a rehabilitation therapist as one of the evaluators in order to confirm the clinical validity and face value of the overall template of our program. Our study used but occupational and physical therapists. Prior testing with the scale showed high correlation between the two groups (Kappa > 0.90). This work is not meant to replace the important role of therapists in the ICU or GPU. In fact, our rollout of this program has not resulted in a decrease in physical therapy interventions in the ICU. This program frees up therapist from the role of having to see every patient before they can be mobilized. This program allows us to use non-therapists to safely, reliably and consistently begin early mobility. The therapist can focus on the more complex cases.

There are numerous scales already in the literature [9-11]. Many of the scale we reviewed were designed as a continuous rather than discrete rating system [12-16]. A continuous scale is very useful for its predictive value regarding specific outcomes. It is less helpful when trying to assign specific interventions. Our scale was designed to be safely and reliably administered by non-therapist. Additionally, many of the interventions are performed by specially trained unlicensed caregivers. These mobility-trained nurses’ aides administer the interventions, record the outcomes and participate in the discussion to advance the mobility level (or decrease it). Most scales in the literature were designed for use by physical therapists. They require specific motions and measurements that may not be intuitive to non-therapist therefore introducing error [17]. Some scales included a psychosocial component which was beyond the scope of our work [18].

Our reliability testing model may seem overly complex. We understand that it does not directly translate to the real life clinical setting. The issue for us was the labile nature of ICU patients. It quickly become clear to us that ICU patients undergoing 2 successive 20-minute mobility evaluation did not react the same in both scenarios. ICU patients become easily fatigued, confused and distracted. Because we use this protocol in the ICU, it was important that we tested all patients deemed clinically stable and awake in the ICU. In many cases patients, especially respirator dependent patients, in the ICU setting are still given sedation to help them rest and recover. This limits their ability to focus and desire to cooperate for extended periods. Forty minutes of physical exertion is unreasonable for many of these patients. Also, sicker patients may not be at the same level of consciousness and coherence throughout the day. Any testing protocol we put together to recreate similar settings for 2 independent examiners seemed clearly substandard. In general, whichever examiner went first usually got a higher mobility level. Once the model was set up, it went smoothly and all parties agreed that is resulted in limited bias.

Limitations of the study include its narrow scope. This is a single institution experience. The verbiage and endpoints were developed and tested for the clinical scenarios and institutional culture specific to us. It is possible the distinct divisions between the 5 points may not be as clear to others. There are also many other mobility scales and strategies available in the literature we did not compare ours to others. The next step will be to compare different approaches to early mobility for ease of use, acceptance and clinical utility.

CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

- Jankowski IM (2010) Tips for protecting critically ill patients from pressure ulcers. Crit Care Nurse 30: 7-9.

- Kleinpell RM, Fletcher K, Jennings BM (2008) Reducing functional decline in hospitalized elderly. In: Hughes RG (eds.). Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, AHRQ Publication, Rockville, USA.

- Perme C, Chandrashekar R (2009) Early mobility and walking program for patients in intensive care units: creating a standard of care. Am J Crit Care 18: 212-221.

- Sim J, Wright CC (2005) The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther 85: 257-268.

- Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) A one-way components of variance model for categorical data. Biometrics 33: 671-679.

- Kupper LL, Hafner KB (1989) On assessing interrater agreement for multiple attribute responses. Biometrics 45: 957-967.

- Pashikanti L, Von Ah D (2012) Impact of early mobilization protocol on the medical-surgical inpatient population: an integrated review of literature. Clin Nurse Spec 26: 87-94.

- Scott T, Mannion R, Davies HT, Marshall MN (2003) Implementing culture change in health care: theory and practice. Int J Qual Health Care 15: 111-118.

- Hodgson C, Needham D, Haines K, Bailey M, Ward A, et al. (2014) Feasibility and inter-rater reliability of the ICU Mobility Scale. Heart Lung 43: 19-24.

- Scherer SA, Hammerich AS (2008) Outcomes in cardiopulmonary physical therapy: acute care index of function. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J 19: 94-97.

- DiCicco J, Whalen D (2010) University of Rochester Acute Care Evaluation: development of a new functional outcome measure for the acute care setting. The Journal of Acute Care Physical Therapy 1: 14-20.

- Skinner EH, Berney S, Warrillow S, Denehy L (2009) Development of a Physical Function outcome measure (PFIT) and a pilot exercise training protocol for use in intensive care. Crit Care Resusc 11: 110-115.

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW (1965) Functional Evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md State Med J 14: 61-65.

- Zanni JM, Korupolu R, Fan E, Pradhan P, Janjua K, et al. (2010) Rehabilitation therapy and outcomes in acute respiratory failure: an observational pilot project. J Crit Care 25: 254-262.

- Rappaport M, Hall KM, Hopkins K, Belleza T, Cope DN (1982) Disability rating scale for severe head trauma: coma to community. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 63: 118-123.

- Thrush A, Rozek M, Dekerlegand JL (2012) The clinical utility of the Functional Status Score for the Intensive Care Unit (FSS-ICU) at a long-term acute care hospital: a prospective cohort study. Phys Ther 92: 1536-1545.

- Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Keith RA, Zielesny M, Sherwin FS (1986) Advances in functional assessment for medical rehabilitation. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation 1: 59-74.

- Akerman E, Fridlund B, Ersson A, Granberg-Axéll A (2009) Development of the 3-SET 4P questionnaire for evaluating former ICU patients’ physical and psychosocial problems over time: a pilot study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 25: 80-89.

Citation: Jackman C, Gammon H, Kane P, Siegert C, Lenane C, et al. (2016) A Reliable Mobility Assessment Tool for Multidisciplinary Use. J Phys Med Rehabil Disabil 2: 009.

Copyright: © 2016 Catherine Jackman, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.