A Review of the Evidence of Care for the Ghanaian Aged

*Corresponding Author(s):

Irene Korkoi AbohSchool Of Nursing And Midwifery, University Of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana

Tel:+233 261774164,

Email:iaboh@ucc.edu.gh

Abstract

Sub-Saharan Africa, a deprived region in the world is rapidly increasing with the aged. This is worrying because of the enormous of issue of ageing. The aim of this paper is to review the evidence of care in a published paper on care of the aged at home. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) framework for systematic literature reviews and Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) methods were used to track the eligibility of the research question. Considering the paucity of the evidence on caring for the aged, this method was the most appropriate for use to explore the preposition. The research was performed using five electronic databases from January 2017 and July 2017 taking into consideration set inclusion and exclusion criteria. Only studies in English were considered and a total of 18 articles met the study criteria. Reviewers pulled out primary studies in the form of quantitative, qualitative and editorial reports. The literature reviewed showed shortcomings in reporting on care for the aged at home and a lack of high-quality scientific evidence for Ghana. Six core themes were generated: neglect of aged care; aged care for the younger generation; aged living arrangements; government neglect; preparedness; and care of the aged in Ghana. The review offered significant insight into care for the aged in their homes. The rigorous approach used provided a good understanding of underlying issues on the needs of the aged.

Keywords

Aged; Aged care, Ghana; Home care; preparedness

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis

PICO: Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome

HIV/AIDs: Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Diseases

SSA: Sub-Saharan Africa

MMAT: Mixed Methods Appraisal Tools

BACKGROUND

In less developed regions including East Asia and Latin America, there is increased in numbers of older adult in the population. There is evidence of a shift in population age structure worldwide which is caused by rapid declines in fertility and mortality [1]. As the world’s population continues to age, forecasts show that this trend will continue [2,3] and the proportion of persons 65years and older is projected to increase sharply in coming years [4,5]. Ghana’s population aged 60 and over will account for more than 11% by 2050, and also account for 21.1% of the global population. Ageing is happening irrespective of socio-economic hardship, widespread poverty, Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Diseases (HIV/AIDS) and COVID 19 pandemic and the rapid evolution of the traditional extended family structure [6].

AGED SUPPORT

Families are the key social groups in which older people are kept and maintained [7], and critical in understanding challenges and opportunities of ageing [8]. The emergence of gerontological interventions has raised concerns about destruction of customary family care systems and a pending “disaster” of old-age sustenance [9,10]. The importance of the role played by the elderly in nation building cannot be over- emphasised. Asiyanbola [11] pointed out that they are the guardians of culture and tradition, peacekeepers during conflicts resolution and promoters in enforcing peace in their various communities; adding that the aged tend to live with their families, usually with an adult son and daughter, with some variation across countries as to the preferred co-resident. Living with or near the family is crucial for maintenance of support since the aged need help with activities such as cooking or shopping, as well as physical and psychological support, particularly when they no longer work for a salary and begin to suffer from illnesses that restrict their capacity to carry out activities necessary for day-to-day survival [12]. In addition to the usual physical, mental and physiological changes associated with ageing, old people are very often disadvantaged by lack of social security for their everyday social and economic needs [13]. Care for needy members is a core element of family life. As also seen elsewhere, older people in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) play roles both as care givers to orphans and vulnerable children in situations of HIV, poverty, and labour-related relocations [14,15] and as recipients of long-term care. Many older persons reach retirement age in a state of poverty and deprivation, with poor access to health care and poor dietary intake. The care and support by the family and community that was previously taken for granted is not there because of changes in society due to urbanization and expansion [16]. This leaves the aged with insufficient personal savings to meet their daily needs [5,16]. The aged are often denied their right to pension, resulting in poor well-being which becomes a crucial concern in view of their dependence on family support networks, as is clearly apparent in most parts of Sub-Saharan Africa [17,18].

Aim

The aim of this paper is to review the evidence of care in a published paper on care of the aged at home in the Ghanaian society.

Methods

A PRISMA scoping review method was used to guide the study where emphasis was laid on collecting and critically analysing studies, using methods that made use of one or more research questions. Considering the absence of evidence of care of the aged living at home, this method was chosen as the most appropriate way to explore what literature was available from a range of scientific sources. For rigour in the review process, the process followed the four stages recommended in the framework developed by Moher et al., [19]: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation and data analysis. Figure 1 is the prisma framework adopted for study.

Figure 1: A PRISMA flow chart showing phases of the literature search for the review.

Figure 1: A PRISMA flow chart showing phases of the literature search for the review.

Literature search stage

The literature research was done from PubMed, EBSCOhost (CINAHL, science Direct), Google scholar and Grey literature. The search duration was from January to May 2017. A thirty-one-year interval (from January 1985 to December 2016) was adopted as the time frame of published articles in view of the fact that current studies in aged care mostly focus on institutional care. The search terms used were elderly care/ aged care AND policy AND assisted living AND Cape Coast Metropolitan area/ Ghana/ sub-Saharan African AND caretakers/caregivers AND community care / home care. This review has been registered and published in the PROSPERO international prospective register of scoping reviews. It is registered under the following number: - CDR42016049096.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies considered eligible for the review were those that were in English, reported findings and presented data on elderly care and on issues and conditions associated with aged persons living at home in Ghana and the sub-Saharan African region. Studies using qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods published in peer-reviewed journals were included. The inclusion criterion for study populations was subjects aged 50years and upwards.

Data collection stages

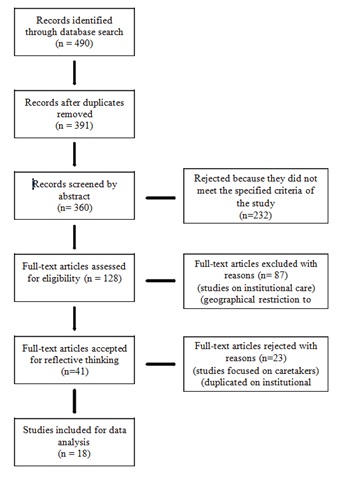

Three reviewers with distinct roles undertook the study. The first reviewer came out with the construct idea and appropriate keywords that were in line to help answer research questions. The second and third reviewers were fed with the idea and they also made their input. The first and second reviewers designed a data collection template by means of google folder and independently extracted data focusing on the proved keywords looking at the title of papers on issues involving the aged ageing in place globally. This approach pulled out about a million and a half articles. The procedure was repeated with a time frame limited to 1985 and 2016. A total of 490 articles were accepted by the two reviewers. The data was edited, those that were overlapping had the duplicates removed thereby arriving at 391. To further narrow the articles to be considered for the study, another template was designed with limitation in geographical access to sub Saharan Africa and to aged being cared for in the community (ageing-in-place) looking at abstract only. Reviewers screened abstracts and realized that 31 studies overlapped and were subsequently removed. So abstract screening started with 360 articles. Abstract of the 360 articles were obtained and independently reviewed by the first and second reviewers. This phase generated 128 papers after rejecting 232 papers which did not meet reviewers laid down criteria. Data was again edited, and duplicated papers removed. The third reviewer always met the two reviewers for discussion before a phase began. After a decision was reached by the three reviewers the 128 papers were given a full text review taking into consideration the research questions and issues of caregivers in assisted living, Ghana and home care. Eighty-seven studies were rejected because they were studies that concentrated on caregivers and restricted to SSA but not on care of the aged. Forty-one papers were conclusively accepted by the reviewers after it was edited, and duplicates removed. The team decided to intuitively read selected articles considering the geographical location of the study and excluding data from institutional care. 18 papers were finally agreed on to be used by the reviewers for the study. From an initial total of 391 studies, 304 were excluded because on closer inspection they did not fully meet the inclusion criteria, resulting in an eventual total of 128 papers of which, 41 were conclusively accepted for the review and 18 finally agreed with.

Data evaluation stage

The final 18 accepted studies were identified for inclusion [Figure 2]. To validate the quality of the eighteen articles, a checklist of 21 items, satisfying five sections from Mixed Methods Appraisal Tools (MMAT), was used to inform judgments on the quality of each article regardless of study type. Each of the 18 articles were individually reviewed for quality by the two reviewers and classified as being good, satisfactory or having some limitations. 10 were classified as good, 5 came out with satisfactory and 3 had some limitations after a face-to-face meeting to analyse the findings and to establish harmony. The review showed scanty literature in caring for the aged in sub-Saharan Africa, because the purpose of the search was to extract the evidence in documented literature on the care of the aged.

Figure 2: Modified PRISMA framework for the review.

Figure 2: Modified PRISMA framework for the review.

Data analysis stage

Following the PRISMA evaluation, analysis of the studies was developed inductively, focusing on how the aged are cared for in their own homes. The data analysis included reduction, display, comparison, conclusion-drawing and verification of the data [19]. Rigorous examination of the displayed data was put into themes. The themes were developed taking into consideration type of study, region of study, number of study participants/respondents and similarities and differences between outcomes in the data. Six themes emerged: neglect of the aged, aged caring for younger generation, aged living arrangements, government attitude, preparedness and care of the aged in Ghana.

RESULTS

Description of the data

The review found in the data selected seven qualitative studies, seven quantitative and four critical reviews, each using either an exploratory descriptive or a case study design. Articles were limited to the sub-Saharan African region: Ghana (seven studies), Nigeria (two studies), South Africa (two studies), Botswana (one study), Kenya (one study) and sub-Saharan Africa (five studies). Most studies focused on caring and health seeking behaviours of the aged. No substantial differences were found between the themes dealt with in the studies despite their diversity of the regional contexts. Number of participants or samples sizes in the studies varied from 5 to 6206. In all the studies, the aged were mostly women, with age ranging from 50 years to 79 years.

EVIDENCE OF CARE

Theme 1: Neglect of care for the aged

There was a strong argument that even though of high priority, the health of older people aged 60 years and above, were deteriorated to the point that where they need care, the responsibility fell on a younger female kin, whose own health, employment and education opportunities was affected [2]. Aboderin and Bread opined that, in sub-Saharan Africa, impaired health in old age affects not only the older individuals themselves, but also families and communities and the wider prospects for development. A large proportion of older Africans lack the requisite care. A WHO report on Adult Health and Ageing in Ghana, showed 96% of older adults with hypertension do not receive adequate treatment for the disorder [20]. There are also certain aspects of behaviour that are unacceptable, such as neglect of the elderly and lack of respect for the elderly [2,20]. Caring for people in need is closely linked to the concept of ubuntu as seen among people in Mpumalanga, South Africa, as an obligation and a symbol of respect [20]. In the absence of formal care, older women are the primary caregivers in the community, and they have a network of friends and relatives they care for when support is needed [21]. Care is also extended to other older people who are neglected, frail, confused or who lack support from family [20]. Sometimes these older people are abandoned, neglected by their families and face physical abuse. Widows in particular are the more likely to suffer abuse and some cases may be subjected to accusations of witchcraft [1].

Theme 2: Aged caring for younger generations

The caring function is very important in everyday settings of poverty or labour-related parental absence. In the urban slums of Nairobi, Kenya, around 30% of older women and 20% of older men (aged 60years and over) care for one or more non-biological child [2,13]. A significant proportion of older adults live with orphaned grandchildren. Across the sub-Saharan African region, around 8% of older adults live with a grandchild who has at least one deceased parent, while 1.7% lived with a grandchild whose parents are both deceased due to the AIDS epidemics [12]. Some older people work because of their economic needs, while others are attracted by the social contacts, intellectual challenges, or sense of value that work often provides [6]. Some are expect to depend on their children but instead have to care for grandchildren, which is an unexpected role changed and very taxing [21]. Making elderly women caregivers, instead of relaxing and enjoying the fruits of their labour. Kimuna and Makiwane [22] showed that older people in Mpumalanga are an important social resource as breadwinners, using their meagre, means-tested pensions and providing basic needs, such as health care and education for the members of their households. Traditionally, older women, cared for their grandchildren when their daughters and son left for work in the fields or in the cities, or when high number of HIV/AIDS-related deaths meant that children needed to be cared for who no longer had parents to support them. Kimuna and Makiwane also found that even though the primary aim of the old age pension in Mpumalanga was to give support to older people, it went towards supporting members of their household rather than the needs of the older people themselves, with the pension benefit becoming the main source of household income. Older women heading households provided care even though they lacked the necessary resources to sustain a family and are in most cases widows who had not inherited anything from their husbands or from the parents of the orphaned grandchildren under their care [22].

Theme 3: Aged living arrangement

There is evidence that education promotes living independently, often as a feature of modernization [23]. Urban elderly do live alone or with their children only as compared to their rural counterparts. This could be due to cultural norm, when better-off family members are required by tradition to support other family members, including co-existing [12]. Zimmer and Dayton [12] add that it is women rather than men that have such living arrangements and they have more children-in-law and grandchildren to live with. Another possibility is that when her husband dies, a woman moves in with her extended family. Men living with children and grandchildren are tied to living with spouse. Household composition is also related to well-being: Well-being of elderly people who are separated is inferior to that of any marital groups. In rural Nigeria, it commonly occurs that women or men who are separated and lived alone are not accorded respect and are often stigmatized and marginalized in ways that affects their health; thus, they experience psychological stress which can have serious effect on their well-being [6]. Despite increasing urbanisation, older people in Ghana live in rural areas where health and social services are inadequate [24].

Theme 4: Government attitude

Government indifference toward the elderly leads in some instances of total neglect of their health and financial needs. In Nigeria, no policy or social security system has been put in place to care for people in their old age. The primary health care system makes no special provision for health care for the elderly and even in the overall health policy no special mention is made of the elderly [6]. According to Adebowale et al., [12] education has strong positive influence on their well-being; educated elderly people are likely to receive higher monthly pension, be more knowledgeable about prevention and treatment of diseases, and live in a clean environment. Kabir and colleagues have documented that education is inversely related to the incidence of diseases among the elderly [4,6]. Some older people reported that they have been affected by HIV/AIDS through loss of community support and neglect of their day-to-day needs [25]. Formal care provision for disabled elderly persons living in the community is not available in Nigeria. Some elderly have some form of disability, did not have a caregiver to help in area of limitation [26].

Theme 5: Preparedness for old age

Former employee of public or private organisation who are entitled to a gratuity or pension from monthly salary deductions while in active service often never receive these dues because of bureaucratic inadequacies in the organisation where they served [6]. As a consequence of poverty and poor infrastructure, elderly people in Ghana and Nigeria not only have reduced life expectancy but also spend more of their lifetimes in poor health. Governments have a relaxed attitude to the family structures which have traditionally provided care for elderly are on the verge of collapse. All these factors have an adverse effect on the health of the elderly and compromise their well-being [6]. To the Ghanaian, a house is a symbol of success, affording its owner respect, love, happiness and security in old age; it is a thing of beauty and it provides a sense of belonging, of ‘home’, both physically and symbolically [27]. People with houses have more properly organised funerals than those without a house. If you don’t have a house, any kind of funeral can be organised for you [27]. However, the dream of having somewhere safe to stay when one is old and dependent does not always come true. Van der Geest [27] was proudly informed by a respondent that when he was a child it was his dream to build a house for himself, which he did by age 45, ‘And now I have my peace, comfort and everything’, Two years later, however, the informant was one of the loneliest and most miserable elderly individuals in the study. He was practically blind, his wife had died, and all his twenty children were living elsewhere; he spent the whole day lying on a bed without a sheet or cloth [27].

Theme 6: Care of the aged in Ghana

The relative merits of maintaining the tradition of home-based care versus embracing a transition to long-term institutional care (nursing homes or aged-care homes, frail-care homes, etc.,) are increasingly a matter of controversy. For most African and African-descent ethnicities, caring for family in the home is regarded as a moral imperative and a family responsibility [28]. This strong sense of family responsibility is seen in African- Americans descents. Traditionally, support in the African culture takes the form of intergenerational reciprocal care [28], which is an obligation and sign of respect [20]. Traditional intergenerational caregiving is still foremost in providing home-based care and community-based care for the sick and the frail. Some South Africans would want to stay in their own homes and not go to an old-age home (i.e., nursing homes) or any frail-care services available. However, as lifespans increase and with global ageing, family responsibility for maintaining home-based care will be difficult to sustain and more older Africans will become institutionalised. Urbanisation leads to a transition from traditional home care to institutionalised care, as children and grandchildren caregivers relocate to cities [28].

It is difficult to get a clear picture of the care that old people in Ghana enjoy. Some successful elderly have been able to give their children good education, resulting in a good social position. These people are usually fortunate to have their children taking good care of them, buying them everything that they need, including clothes and luxury items such as clocks, watches, radios, lanterns and ornaments [29]. The houses of such people are often filled with children, nieces, nephews and grandchildren. Their good quality of life attracts relatives who bring company and presents. The quality of life of the less well-to-do elderly is harder to quantity. There are elderly people who contradict themselves, complaining at time that they have no money for food, that their children are far away and seldomly visit them, and that their children do not send them enough money to live comfortably, and at other times praising their children for the way they look after them. In admission that their children’s neglect would call shame on them. Many emphasise that their children do what they can to assist them [30]. Whether it was the gloomy side of their situation or the bright side that they emphasised when they were interviewed depended on the situation in which the interview took place. If an old person’s relationship with the interviewer was easy and there were no other people listening, the interviewee would be more inclined to reveal his or her worries; otherwise they preferred to keep up a respectable appearance [30]. The real situation in receiving care in Ghana is far more complex, several people usually provide care, and who does what is very much a matter of who happens to be around. Care is often managed on a day-to-day basis, with considerable improvisations [30].

DISCUSSION

Despite the large number of articles that focused on the issue of the aged, only a few addressed caring of elderly people living at home. The studies reviewed were studies from countries in sub-Saharan Africa that focused on quality of care for the aged. Not all 18 studies dealt with every one of these themes, but in at least nine of the studies most of them were involved. Neglect of the aged, aged caring for younger relatives, and aged’s living arrangements were dealt with in 9 articles. Government neglect, preparedness for old age and care of the aged in Ghana were also discussed in 9 articles. However, only one article explicitly spelt out the type of care elderly people received at home. It was easier to identify support given to younger relatives by the aged and how tired they get. The article also showed how the elderly people’s meagre pensions go to support the welfare of younger relatives, leaving the pensioners with nothing. Men are not strong and brave enough to cope with loneliness and the shame of being single, so they are always either married and living with a spouse or living with a single child [6]. In the Ghanaian Akan community, investment in building house thinking that it will be a guarantee of care in one’s old age may be a detriment of care, so that one could end up lonely in one’s old age [30]. There was a lot consistency among the variables, possibly reflecting similar results emanating from the view that the SSA culture and behaviour to care was almost similar. Attention was paid to generalization, interpretation and application of the results obtained. In the context on the care of the aged in their homes, outcome was on frail, demented and adult caregivers. However, conducting a scoping review was no guarantee that all articles used were relevant, because there could be articles in other languages than English that could be useful to study the topic.

IMPLICATIONS

This review provided an up-to-date overview of the care of aged living at home and indicates there is no obvious difference in the care given to these people, regardless of the cultural context. The review identified useful literature on care of the aged in SSA. Policy makers need to emphasise the importance of looking after senior citizens. They also need to help their populace plan properly for their own old age, regardless of where they live and they must be knowledgeable about the needs of elderly in policy and decision making, especially in an era scarce resource.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the author (IKA) on reasonable request.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares that there is no competing interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

IKA designed, implemented the review, and drafted the manuscript. AAD read the manuscript for its content validity and help with publication of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Dosu G (2014) Elderly Care in Ghana. HKAG publications, London, UK.

- Aboderin IAG, Beard JR (2015) Older people's health in sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet 385: 7-11.

- WHO (2012) Good health adds life to years: Global brief for World Health Day 2012. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Gómez-Olivé FX, Thorogood M, Clark BD, Kahn K, Tollman SM (2010) Assessing health and well-being among older people in rural South Africa. Global Health Action 3: 2126.

- Collinson MA, Tollman SM, Kahn K (2007) Migration, Settlement Change and Health in Post-Apartheid South Africa: Triangulating Health and Demographic Surveillance with National Census Data. Scand J Public Health Suppl 69: 77-84.

- Adebowale SA, Atte O, Ayeni O (2012) Elderly Well-being in a Rural Community in North Central Nigeria, sub-Saharan Africa. Public Health Research 2: 92-101.

- Keating N (2011) Critical Reflections on Families of Older Adults. Adv Gerontol 24: 343-349.

- Therborn G (2006) African families in a global context. Nordiska Afrika institute, Uppsala, Sweden.

- Aboderin I (2010) Global aging: Perspectives from sub-Saharan Africa. In: Dannefer D, Phillipson C (eds.). The SAGE Handbook of Social Gerontology. Sage, London, UK.

- Ferreira M (1999) Building and advancing African gerontology. Southern African Journal of Gerontology 8: 1-3.

- Asiyanbola AR (2009) Spatial Behaviour, Care and Well Being Of the Elderly in Developing Country - Nigeria. IFE Psychologia 17: 1.

- Zimmer Z, Dayton J (2005) Older adults in sub-Saharan Africa living with children and grandchildren. Popul Stud (Camb) 59: 295-312.

- Aboderin I, Ho?man J (2013) Care for dependent older people in sub-Saharan Africa: recognizing and addressing a “cultural lag”. 20th International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics World Congress of Gerontology and Geriatrics, Seoul, South Korea.

- Hosegood V. Timæus IM (2005) The impact of adult mortality on the living arrangements of older people in rural South Africa. Aging and Society 25: 431-444.

- Posel D, Fairburn JA, Lund F (2006) Labour migration and households: A reconsideration of the effects of the social pension on labour supply in South Africa. Economic Modelling 23: 836-853.

- Charton KE, Rose D (2001) Nutrition Among Older Adults in Africa: The Situation at the Beginning of the Millenium. J Nutr 131: 2424-2428.

- Van de Walle E (2006) African households: censuses and surveys. Journal of social science and medicine 62: 2411-2419.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2002) World Population Ageing: 1950-2050. United Nations Publications, New York, USA.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6: 1000097.

- Bohman DM, van Wyk NC, Ekman SL (2011) South Africans’ experiences of being old and of care and caring in a transitional period. Int J Older People Nurs 6: 187-195.

- Lindsey E, Hirschfeld M, Tlou S (2003) Home-based Care in Botswana: Experiences of Older Women and Young Girls, Health Care Women Int 24: 486-501.

- Kimuna SR, Makiwane M (2007) Older People as Resources in South Africa: Mpumalanga Households. J Aging Soc Policy 19: 97-114.

- United Nations, Department of Economics and Social Affairs (2017) World Population Ageing 2017. New York, USA.

- Debpuur C, Welaga P, Wak G, Hodgson A, Self-reported health and functional limitations among older people in the Kassena-Nankana District, Ghana. Journal Global Health Action 3.

- Kyobutungi C, Ezeh AC, Zulu E, Falkingham J (2009) HIV/AIDS and the Health of Older People in the Slums of Nairobi, Kenya: Results From a Cross Sectional Survey. BMC Public Health 9: 153.

- Gureje O, Oladeji BD, Abiona T, Chatterjee S (2014) Profile and Determinants of Successful Aging in the Ibadan Study of Ageing. J Am Geriatr Soc 62: 836-842.

- Van der Geest S (1998) Yebisa Wo Fie: Growing Old and Building a House in the Akan Culture of Ghana. J Cross Cult Gerontol 13: 333-359.

- Bohman DM, van Wyk NC, Ekman SL (2009) Tradition in Transition--Intergenerational Relations with Focus on the Aged and Their Family Members in a South African Context. Scand J Caring Sci 23: 446-455.

- Van der Geest S (1995) Old People and Funerals in a Rural Ghanaian Community: Ambiguities in Family Care. Southern African Journal of Gerontology 4: 33-40.

- Van der Geest S (2002) Respect and reciprocity: Care of elderly people in rural Ghana. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 17: 3-31.

Citation: Aboh IK, Druye AA (2020) A Review of the Evidence of Care for the Ghanaian Aged. J Gerontol Geriatr Med 6: 052.

Copyright: © 2020 Irene Korkoi Aboh, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.