A Sequential Explanatory Mixed Method Study to Identify Human Rights Violations and Asses the Psychosocial Health Status of the Internally Displaced Women of North-West Pakistan

*Corresponding Author(s):

Hassan Mehmood KhanFata Development Program Fdp, Deutsche Gesellschaft Fuer Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Peshawar, Pakistan

Tel:+92 3459022992,

Email:dr.hassanmehmoodkhan@gmail.com

Abstract

Background

Millions of people are displaced each year due to conflicts worldwide, majority of them being displaced internally in their own countries. Although the number of Internally Displaced People (IDPs) is two times that of refugees, the IDPs don’t get the aid meant for refugees as they don’t cross international borders. Due to the ongoing war on terror, millions of people were displaced internally in North-West Pakistan including women and children, and there were press reports of human rights violations and psychosocial ill health among them. The objectives of our study were to estimate psychiatric morbidities among the internally displaced women of North-West Pakistan and to identify the human rights violations of these women.

Methods

A sequential explanatory design of mixed method inquiry was used for this study. In the quantitative phase data was collected for psychiatric morbidities using a screening tool General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) 28 and for human rights violations and physical health related needs of the internally displaced women through a semi structured questionnaire from 308 displaced women. In the qualitative phase data was collected for the human rights violations through in-depth interviews with 10 displaced women and 5 displaced men.

Results

According to our findings, 99.7% of the displaced women were scoring above the threshold for psychiatric morbidity and every one of them could be considered to be suffering from psychosocial ill health and their human rights and the rights as citizens of a country have been violated and the United Nations (UN) guiding principles on internal displacement were not being followed.

Conclusion

Of those studied, nearly all the internally displaced women of North-West Pakistan could be considered to be suffering from psychosocial ill health and evidence of human rights violations was discovered and there is a serious cause for concern regarding the violation of human rights of these IDPs. Their rights as citizens of a country have also been violated and the UN guiding principles on internal displacement are not being followed. The policy makers and humanitarian agencies should look into it by providing them all the basic necessities of life including food, water, privacy and protection of their honor, which were found to be lacking; and by initiating long term programs to take care of their mental health and rehabilitation as soon as possible.

INTRODUCTION

Background

At the start of 2011, nearly 34 million people were displaced either internally or to other countries and regions around the world due to armed conflicts and political violence [5]. Internally Displaced People (IDPs) makes the largest group amongst the displaced and at the start of 2011 as many as 14.7 million people were internally displaced in 27 countries, though the total number of IDPs from conflict could be as high as 27.5 million [5]. By December 2015, there were more than 65 million displaced people due to conflicts across the globe and 50% of them were females [6].

There is an ongoing need to develop a culturally appropriate mental health services program for the displaced refugees [7]. A well planned social support enables resettled populations to meet their basic needs and improve their psychosocial health status [8]. Study findings recommend the need of continuous research on the psychosocial health and well-being of the resettled refugees and displaced people in order to develop effective resettlement strategies [9]. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), forced displacement will continue to grow in the next decade [5].

The IDPs mostly have no other option than to seek assistance, protection, safety and security in the temporary camps in the destination areas. Whenever the humanitarian assistance in a camp is not organized and coordinated the vulnerability of the camp population increases. Gaps in humanitarian assistance in the camps lead to inequitable provision of services and inadequate protection [10]. Studies show that more than 90% of the IDPs don’t feel safe in the temporary camps they have to live in [11].

IDPs and human rights

IDPs and psychiatric morbidities

Some of the most common health or health related problems among the IDPs are psychiatric morbidities and human rights violations [16]. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD) and depression are common amongst the IDPs [17]. Major depressive disorders and suicidal tendencies are common in the internally displaced population [18]. A study in Uganda provides evidence on the impact of mental health of deprivation of basic goods, traumatic events, fear and uncertainty among displaced people [19]. In a study in Sri Lanka a clear dose-effect relationship between the exposure to conflict and war and PTSD severity was found among children [20]. In a study about the mental health of refugees following state-sponsored repatriation from Germany it was found that psychological stress among the refugees was of a considerable magnitude [21]. A cross sectional survey of the post conflict mental health status of the affected people in Sudan provides evidence of high levels of mental distress and associated risk-factors among the affected population, recommending a comprehensive psychosocial assistance in the affected region [22]. According to a systematic review the prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder ranged from 11-23%, anxiety from 25-77%, and major depression from 11.5-57% among Tibetan refugees [23]. According to another study in post war Serbia, 13.0% participants had symptoms of PTSD, and 49.2% had symptoms of depression [24]. According to a survey in the Indian Kashmir valley, the ongoing conflict in the valley had a huge toll on the psychosocial health of the population with over one third of the participants having symptoms of psychological distress and majority of them being women [25]. According to an epidemiological study, 48% of the Somali and 32% of Rwandese refugees living in a refugee settlement were found to be suffering from PTSD [26]. In another study on the mental health status of the people displaced from Bosnia and Herzegovina due to conflict, mental health challenges were found to be present in more than 41% of those displaced [27]. Another study revealed that 62% of the Hurricane Katrina evacuees met the threshold criterion for Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) [28]. Refugees showed very high levels of psychosomatic and depressive symptoms as compared to civilians and soldiers in a longitudinal study in Croatia [29]. A study in the Tsunami affected regions found that the displaced survivors of Tsunami had significantly higher psychiatric morbidities as compared to the non-displaced people of the region [30]. A thesis that studied the mental health outcomes of the population that was displaced temporarily from Kosovo to Sweden showed that the prevalence of PTSD was 37% at baseline and increased significantly to 80% within 18 months of being displaced [31]. A brief review of research findings of the mental health consequences of war by Murthy and Lakshminarayana report that 42-72% respondents in Afghanistan, 17% in the Balkans, 15-55% in Cambodia, two thirds in Chechnya, 60-87% in Iraq, 9-76% in Israel, 16-42% in Lebanon, 11-54% in Palestine, about 25% in Rwanda and 64% in Sri Lanka had symptoms of psychiatric disorders [32].

Internally displaced women

“The differential impact of armed conflict and specific vulnerabilities of women can be seen in all phases of displacement” [33].

Studies show that women and children are the most vulnerable population among the displaced people and psychosocial health needs are largely unmet in these populations [18]. Most of the Internally Displaced Women (IDW) report that they don’t have autonomy to access health care and majority of them also report difficulties in breastfeeding due to the displacement [18]. There are restrictions on the freedom of movement and expression of the displaced women [18]. Women are also at risk of violence both within and outside the camps and displacement are reported to compromise resilience in women [34]. Studies on Internally Displaced Women (IDW) suggest that health services to them are severely lacking, the conditions in the camps established for them are unhygienic with lack of water [11]. The human rights of the internally displaced women cannot be realized without an appropriate understanding of the scenario they face and the question of IDPs cannot be solved without addressing the concerns and needs of the internally displaced women [11].

Research shows that conflict and displacement had a much greater effect on the health of the internally displaced women as compared to the health of the internally displaced men [19]. Studies provide evidence on the impact of displacement and deprivation of basic goods and services on both mental and physical health of the IDPs especially women [19].

IDPs of North-West Pakistan

Internally displaced women of North-West Pakistan

UN Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women

In this convention, discrimination against women was described as “any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field” [36]. Under article 2 of the convention the state parties condemned all kind of discrimination against women and agreed to adopt a policy of eliminating discrimination against women by using all appropriate means including legislation without any delay [36]. Under article 5 the state parties agreed to eliminate all kind of prejudices and social and cultural customs and practices based on inferiority or superiority of either of the sexes [36]. According to articles 6 and 12 of the convention, the state parties agreed to take all kinds of steps to eliminate discrimination against women in access to education and health care respectively [36].

The UN guiding principles on internal displacement

This study was conducted to explore the human rights status and the sufferings of the internally displaced women of North-West Pakistan during the conflict and in the whole process of displacement to see if these displaced women were getting the rights as declared in the universal declaration of human rights and if the UN guiding principles on internal displacement are being followed by the authorities or not; to explore if any kind of discrimination was being done against these women keeping in view the UN Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW); to identify the needs of these displaced women to inform the policy makers and humanitarian agencies and organizations to guide the future direction of humanitarian assistance for the internally displaced people and to explore the mental health status of these displaced women by assessing four subjective indicators of mental health i.e., somatic complaints, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction and depressive feelings.

METHODS

Study objectives

2. To identify the human rights violations of the internally displaced women of North-West Pakistan

Study setting

Study design

General health questionnaire 28 (GHQ 28)

Using the alternative binary scoring method (with the two least symptomatic answers scoring 0 and the two most symptomatic answers scoring 1), the GHQ 28 classify any score exceeding the threshold value of 4 as achieving ‘psychiatric caseness’ [47], meaning that any person with the score of more than 4 on the GHQ 28 should be considered to be suffering from psychiatric morbidity. It should be noted here that the GHQ 28 is a screening tool and not a diagnostic tool and psychiatric caseness here is a probabilistic term and GHQ 28 is not usually used for predictive purposes however if such respondents presented in general practice, they would be likely to receive further attention [47].

The GHQ 28 has been developed by David Goldberg and has been validated in various languages and used on different populations [49]. Both English and Urdu versions of the GHQ 28 have been used and validated on Pakistani populations and both were found reliable for screening psychiatric morbidities in Pakistani populations [50]. The reliability coefficients of GHQ 28 have ranged from 0.78 to 0.95 in various studies [47]. The reliability coefficient of the Urdu version of the GHQ 28 has been reported as 0.90 [50]. The validated Urdu version of the tool was translated into Pashto by a bilingual expert and was back translated to Urdu by another bilingual expert. The needed amendments were made into the Pashto translation of the tool after this process of translation and back translation to make it as equal to the validated version as possible and was again translated and back translated by a bilingual expert before pretesting on a similar population and finalizing it for the formal data collection process. Data for the quantitative phase was collected by data collectors who were trained by the Principal Investigator before starting data collection.

In-depth interviews

Pretesting of instruments

Study population

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

1. The women and men living in the temporary camps for the IDPs but not displaced from Bajaur or Momand agencies of FATA and Malakand Division and present in the camp at the time of data collection as visitors or relatives of the IDPs living in Peshawar or elsewhere

2. The women and men not giving consent

3. The women and men who are not able to talk or express their selves due to any pathological or anatomical problem like speech disorders

Sampling

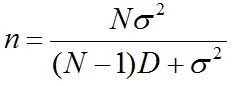

Sample size

Where

N = 16827 B = 0.1(10%)

σ = (0.84 - 0.16) = 0.68 Zα/2 = 1.96

σ = (0.84 - 0.16) = 0.68 Zα/2 = 1.96After adjusting for an assumed dropout rate (including refusal/non-response) of 10% gave us the sample size of at least 284 adult female IDPs for the study to meet our objective. For the quantitative phase data was collected from 308 adult internally displaced women.

For the qualitative portion purposive sampling was done for the in-depth interviews with a purposive sample of participants and data was collected through in-depth interviews with 5 adult male and 10 adult female IDPs and the process was stopped once saturation was reached.

Data analysis

The qualitative data was analyzed manually and themes were generated from nodes and sub nodes as per the replies from the study participants.

Integration

Ethical considerations

RESULTS

The quantitative phase

Demographic information

| Category | No. of Participants (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Age group | ||

| 18-25 years | 92 | 29.87012987 |

| 26-35 years | 72 | 23.37662338 |

| 36-45 years | 71 | 23.05194805 |

| 46-55 years | 30 | 9.74025974 |

| 56-65 years | 16 | 5.194805195 |

| 66-75 years | 15 | 4.87012987 |

| >75 years | 12 | 3.896103896 |

| Total | 308 | 100 |

| Education level | ||

| Illiterate | 251 | 81.49350649 |

| Primary or less | 41 | 13.31168831 |

| Middle | 6 | 1.948051948 |

| Matric | 8 | 2.597402597 |

| Intermediate | 1 | 0.324675325 |

| Graduate | 1 | 0.324675325 |

| Total | 308 | 100 |

| Area of origin | ||

| Bajaur agency | 179 | 58.11688312 |

| Momand agency | 96 | 31.16883117 |

| Malakand division | 33 | 10.71428571 |

| Total | 308 | 100 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 194 | 62.98701299 |

| Unmarried | 67 | 21.75324675 |

| Widow | 47 | 15.25974026 |

| Total | 308 | 100 |

Table 1: Demographic information of the study participants (Quantitative Phase).

Human rights status

More than half of the participants (n = 159, 51.6%) said that their family member or members have been killed since the conflict started, either in their home town before displacement or in the process of displacement while more than half of them (n = 180, 58.4%) also said that they have witnessed killings themselves during the conflict in their hometown before displacement. Almost 60% (n = 179) of the participants said that they have witnessed torture/abuse during the conflict in their home town before displacement while almost 25% (n = 74) of the participants said that they have witnessed torture/abuse in the process of displacement or in the camp. More than 30% (n = 93) of the participants responded that either healthcare services are not provided to them in the camp when they or anyone in their family gets ill or the treatment provided is not enough or not effective. Majority of the participants (n = 264, 85.7%) were not satisfied with living in the camp. When the participants were asked about their greatest need in the camp, their response was electricity (n = 103, 33.4%), followed by food (n = 53, 17.2%) and money (n = 41, 13.3%) respectively. More than 95% (n = 294) of the respondents wanted to return to their homes as soon as possible but more than 92% (n = 285) of them had no idea of their future or the possibility of their return to their homes.

Psychiatric morbidities

| Somatic Complaints | ||||

| Score | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent |

| 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| 1 | 5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| 2 | 15 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 6.8 |

| 3 | 33 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 17.5 |

| 4 | 43 | 14 | 14 | 31.5 |

| 5 | 8 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 34.1 |

| 6 | 77 | 25 | 25 | 59.1 |

| 7 | 126 | 40.9 | 40.9 | 100 |

| Total | 308 | 100 | 100 | |

| Anxiety & insomnia | ||||

| 0 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| 1 | 7 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.9 |

| 2 | 38 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 15.3 |

| 3 | 51 | 16.6 | 16.6 | 31.8 |

| 4 | 27 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 40.6 |

| 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 41.6 |

| 6 | 23 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 49 |

| 7 | 157 | 51 | 51 | 100 |

| Total | 308 | 100 | 100 | |

| Social dysfunction | ||||

| 0 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| 1 | 20 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 7.1 |

| 2 | 6 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 9.1 |

| 3 | 28 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 18.2 |

| 4 | 16 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 23.4 |

| 5 | 34 | 11 | 11 | 34.4 |

| 6 | 82 | 26.6 | 26.6 | 61 |

| 7 | 120 | 39 | 39 | 100 |

| Total | 308 | 100 | 100 | |

| Depressive feelings | ||||

| 0 | 11 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.6 |

| 1 | 10 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 6.8 |

| 2 | 72 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 30.2 |

| 3 | 29 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 39.6 |

| 4 | 19 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 45.8 |

| 5 | 32 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 56.2 |

| 6 | 24 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 64 |

| 7 | 111 | 36 | 36 | 100 |

| Total | 308 | 100 | 100 | |

| Somatic Complaints | ||||

| Score | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent |

| 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| 1 | 5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| 2 | 15 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 6.8 |

| 3 | 33 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 17.5 |

| 4 | 43 | 14 | 14 | 31.5 |

| 5 | 8 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 34.1 |

| 6 | 77 | 25 | 25 | 59.1 |

| 7 | 126 | 40.9 | 40.9 | 100 |

| Total | 308 | 100 | 100 | |

| Anxiety & insomnia | ||||

| 0 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| 1 | 7 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.9 |

| 2 | 38 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 15.3 |

| 3 | 51 | 16.6 | 16.6 | 31.8 |

| 4 | 27 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 40.6 |

| 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 41.6 |

| 6 | 23 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 49 |

| 7 | 157 | 51 | 51 | 100 |

| Total | 308 | 100 | 100 | |

| Social dysfunction | ||||

| 0 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| 1 | 20 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 7.1 |

| 2 | 6 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 9.1 |

| 3 | 28 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 18.2 |

| 4 | 16 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 23.4 |

| 5 | 34 | 11 | 11 | 34.4 |

| 6 | 82 | 26.6 | 26.6 | 61 |

| 7 | 120 | 39 | 39 | 100 |

| Total | 308 | 100 | 100 | |

| Depressive feelings | ||||

| 0 | 11 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.6 |

| 1 | 10 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 6.8 |

| 2 | 72 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 30.2 |

| 3 | 29 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 39.6 |

| 4 | 19 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 45.8 |

| 5 | 32 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 56.2 |

| 6 | 24 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 64 |

| 7 | 111 | 36 | 36 | 100 |

| Total | 308 | 100 | 100 | |

Table 3:Total score on GHQ 28.

| Age Group | Mean | N | Std. Deviation | Median | Minimum | Maximum | % of Total N |

| 18 - 25 Years | 21.43 | 91 | 6.922 | 25 | 0 | 28 | 29.50% |

| 26 - 35 Years | 21.35 | 74 | 6.033 | 24 | 6 | 28 | 24.00% |

| 36 - 45 Years | 18.73 | 70 | 7.918 | 19.5 | 5 | 28 | 22.70% |

| 46 - 55 Years | 17.53 | 30 | 5.841 | 15 | 8 | 28 | 9.70% |

| 56 - 65 Years | 20.69 | 16 | 7.012 | 24.5 | 8 | 27 | 5.20% |

| 66 - 75 Years | 23.21 | 14 | 4.742 | 26 | 15 | 28 | 4.50% |

| >75 Years | 26.46 | 13 | 3.55 | 28 | 15 | 28 | 4.20% |

| Total | 20.67 | 308 | 6.905 | 24 | 0 | 28 | 100.00% |

| Education level | |||||||

| Illiterate | 20.2 | 251 | 6.726 | 22 | 5 | 28 | 81.50% |

| Primary or Less | 23.33 | 42 | 6.945 | 26 | 0 | 28 | 13.60% |

| Middle | 23.2 | 5 | 6.907 | 26 | 11 | 28 | 1.60% |

| Matric | 23.88 | 8 | 5.718 | 25.5 | 10 | 27 | 2.60% |

| Intermediate | 5 | 1 | . | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0.30% |

| Graduate | 6 | 1 | . | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0.30% |

| Total | 20.67 | 308 | 6.905 | 24 | 0 | 28 | 100.00% |

| Area of origin | |||||||

| Bajaur agency | 22.72 | 180 | 6.316 | 26 | 0 | 28 | 58.40% |

| Momand agency | 17.23 | 96 | 6.228 | 15 | 5 | 28 | 31.20% |

| Malakand division | 19.5 | 32 | 7.783 | 24.5 | 5 | 28 | 10.40% |

| Total | 20.67 | 308 | 6.905 | 24 | 0 | 28 | 100.00% |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 21.77 | 193 | 6.186 | 25 | 5 | 28 | 62.70% |

| Unmarried | 20.38 | 68 | 7.109 | 23 | 0 | 28 | 22.10% |

| Widow | 16.6 | 47 | 7.923 | 15 | 5 | 28 | 15.30% |

| Total | 20.67 | 308 | 6.905 | 24 | 0 | 28 | 100.00% |

| Duration of displacement | |||||||

| 3 months or less | 17.88 | 41 | 8.019 | 17 | 0 | 28 | 13.30% |

| More than 3 months up to 6 months | 23.6 | 40 | 5.042 | 25 | 8 | 28 | 13.00% |

| More than 6 months | 20.66 | 227 | 6.787 | 23 | 5 | 28 | 73.70% |

| Total | 20.67 | 308 | 6.905 | 24 | 0 | 28 | 100.00% |

Table 4: Cross analysis of GHQ 28 Scores.

The qualitative phase

Water, food and clothes

Food is another basic necessity of life and most of the participants were purchasing food stuff from market on their own because the food provided to them at the camp by the camp authorities and as aid from different sources was either not enough for the large family size or was of a poor quality.

“Only 1 bag flour is given at the camp per month but that flour is also not good, at times we have found worms in it. And at one time I was shocked to see a dead frog in the flour bag they gave me here in this camp. Now when I get it I sell it in bazaar and get more clean flour for ourselves” (Male, 32 years, Bajaur).

As the participants had to run for their lives and leave their homes suddenly because they were not informed before the military operation was started in their areas, so most of them could not manage to bring any clothes and other stuff along them to the camp and everything was left behind and most of them reached the camp with just one or two pairs of clothes with them and they had to spend many days in the clothes they were wearing when they left home until they purchased some clothes for themselves or were given used clothes by some local people.

Reason for displacement

“Both the Taliban and the military are killing innocent people and our children, so how can we stay there, I cannot watch my children being slaughtered by the Taliban or burnt alive by the military bombing” (Female, 58 years, Momand).

One of the themes emerging was that the military was bombing the villages and homes of innocent people of the area especially in Bajaur and Charmang areas and leaving the localities where the militants were operating untouched and unharmed. It was revealed that the Taliban were operating in the main Bajaur agency while the army was bombing and destroying villages in Charmang area in the suburbs of Bajaur.

Freedom of movement

Regarding the freedom of movement in their home towns before displacement, the women were allowed to move freely at their will but only inside their homes especially when the activities of the militants started there and then the security forces entered the area, after that they were not able to go outside their homes or to the market either because of fear of the Taliban or due to curfews imposed by the military or restrictions on them by their men as they have to perform strict “pardah”. Before the conflict they were able to move around in the area and go to the market but still in “pardah” (Vail). Once the conflict between the Taliban and the security forces was started then not only the females but the men were also not able to move freely mostly because of curfews to such an extent that they could not even go to the mosque to pray. Curfews were described as one of the major restriction on the freedom of movement in their home towns after the conflict started and the participants could not go out of their houses because of the fear of being killed as according to the participants any one seen outside in the curfew hours was shot dead on the spot without any investigation.

“Before coming here, we could move freely in our open and vast houses at our will, but not outside in the bazaar in those conditions when Taliban didn’t allowed women to move around in the bazaars and were punished and also our men wouldn’t allow us to go out because of that fear” (Female, 27 years, Momand)

Displacement journey

“It was a very hard journey for us. We were stopped at many places by “Taliban” and searched us and also in many places by military forces and they searched us also including our females. We had to walk for miles on foot in the mountains with no food or water and at times we got some transport for some distance. It took us more than 24 hours to reach here and normally it’s a journey of only 3 hours. And then when we reached here we were sitting on the road for 17 days in the open air and for 17 days nobody gave us any tent or anything and me and my 4 sisters spent 17 days and nights here on the road” (Male, 18 years, Bajaur).

The participants were very upset with the sudden start of bombing on their villages by the military without informing them or taking them to safety due to which they had to suffer a lot in the displacement journey. Therefore the participants used very harsh words while describing their displacement. Apart from other hardships on the displacement journey there were also incidents of harassment of the lonely helpless females.

Daily life activities

“We don’t want to be here like this, and what can we do here? Nothing, just spending time here because we have no other choice. We are not living here on our own happiness but we are forced to live here in these conditions. The females are held inside their tents 24 hours day and night, they can’t do anything. I don’t know for what sin we are being punished by Allah like this we were living in our house peacefully everyone was happy we never thought that this will happen to us. The females were in “pardah” there and their honor was not destroyed there and they were not humiliated like they are here” (Male, 32 years, Bajaur).

Washrooms/toilets/privacy

DISCUSSION

This is one of the first studies to quantify the factors that influence the overall physical and mental health of internally displaced persons in this region. Studies in the past have provided evidence that deprivation of basic goods and services, fear and uncertainty has a negative effect on the physical and mental health of the displaced people [19]. A study in Uganda also found that lack of safety in the camps had a strong negative association with mental health of the inhabitants of the camp [19]. In the south Asian region, systems of care and protection in temporary camps are mostly gender insensitive [55]. Our study has quantified all these factors among the internally displaced women of North-West Pakistan.

Psychiatric morbidities

Prolonged exposure to traumatic events is associated with higher levels of mental health problems and poorer physical health [48], and witnessing extreme violence is also associated with psychosocial and mental health problems like depression, generalized anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder [48,57,58]. Nearly all of the people interviewed wished to return to their place of origin but could not do so as the situation was still not normal there. Attention must be paid to the psychosocial health of the study population since prolonged states of psychiatric morbidities can cause changes in patterns of living that are associated with physical and mental damage [48,59]. A study in South Darfur Sudan showed a considerable high prevalence of depression which was considered to be a challenge for the humanitarian agencies in Sudan [18]. Another study in Uganda provides evidence on the impact on health of deprivation of basic goods and services, traumatic events, and fear and uncertainty amongst displaced and crisis affected populations [19]. Among the consequences of war, the impact on the mental health of the civilian population is one of the most significant and studies of the general population in different regions of the World show a definite increase in the incidence and prevalence of mental disorders [33]. In one study of links between traumatic experiences during the 1994 Rwandan genocide, nearly a quarter of the respondents were found to have symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD) [60]. Another study of mental health and attitudes among Kosovar Albanians following the 1998–1999 war, revealed an association between traumatic events during the war, mental health disorders and impaired social functioning [60,61]. Even according to the DSM IV system (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders number IV) [62], anxiety and depression have been found to be more common in trauma-affected people than was originally assumed [58,63,64], but although nearly all people affected by war and conflicts will suffer various negative responses such as nightmares and fears, they will not all develop psychiatric disorders [48] because there are individual ways of adapting to such stressful conditions that should not be overlooked [48]. Although conflict related mental health remains a comparatively neglected area of research, but current evidence suggests that mental disorders increase in conflict situations, and that human rights violations in such situations may also have negative impacts on mental health of the people living in the conflict zones [60,65]. Thus the findings of our study regarding the psychiatric morbidities are consistent with the findings of similar studies in different parts of the World. Like other indirect conflict related mortality and morbidity, negative mental health impacts are also part of the overall human cost of any conflict, and should be included in the broader impact assessments of conflicts [60].

Human rights violations

The universal declaration of human rights

The UN guiding principles on internal displacement

The UN convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women

Study limitations

RECOMMENDATIONS

The following recommendations have been based on the findings of this study:

1. The camps for the IDPs should be established at locations with similar weather conditions to those of their places of origins and not in places with extreme weather conditions

2. The people that are being displaced should be informed before any action is started and they should be settled properly and safely to safer locations before starting any operations in their areas

3. While establishing a camp for the IDPs the cultural norms and values should be considered and taken care of like in the establishment of washrooms and toilets and privacy

4. The IDPs rehabilitation programs should include a mental health component

5. Measures should be taken so that the education of the displaced children does not suffer and education facilities should be made available for both girls and boys

6. Enough and healthy food and drinkable water supply must be made available in all the IDP camps

7. Efforts should be made to follow the UN’s Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights while dealing with the IDPs especially women

8. The government of Pakistan should take all those measures to which they have agreed to by becoming a signatory to the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

CONCLUSION

The findings of our study show that the internally displaced women of North-West Pakistan and their families had not enough food and clothes, were receiving unhealthy food items, the water provided to them was too hot to use in the hot weather conditions of the camp, were not having proper washroom/toilet facilities and were not provided privacy and security in the camp. The findings also show that the healthcare services provided to the camp inhabitants were not satisfactory, there were restrictions on the movement of women, education of the children was suffering and the women were facing harassment and hardships during the process of displacement. The participants were not informed before being forced to flee their homes, their family members were being killed and tortured during the conflict and the prolonged displacement was compromising their physical and psychosocial health. There was uncertainty about their future and many of their friends and relatives were still trapped in their home towns in the conflict zone and on their way to the camps. Our findings indicated that 99.7% of the displaced women were suffering from mental health problems such as anxiety and depression. The internally displaced women of North-West Pakistan are not given the same rights as other citizens of the country. No informed consent was taken from them before being forced to flee their homes. They are denied the right to liberty, security and education, and they are subjected to inhuman and degrading treatment and are denied privacy in the camp. They are not provided a standard of living adequate for health and well being and there is discrimination going on against women in access to education, health and freedom of movement. The human rights situation in the IDP camps of North-West Pakistan is contrary to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement are not being followed in North-West Pakistan. The policy makers, national & international humanitarian agencies should look into the matter especially by establishing such camps at locations not having extreme weather conditions and by providing them all the basic necessities of life including food, water and privacy and protection of their honor, which were found to be lacking in the camp; and also long term programs are needed to take care of their mental health and rehabilitation as soon as possible because 99.7% of the participants could be considered to be suffering from psychiatric morbidities and wanted to return safely to their homes as soon as possible.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

IDP-Internally Displaced People

GHQ-General Health Questionnaire

UN-United Nations

UNHCR-United Nations Refugee Agency

WHO-World Health Organisation

IDW-Internally Displaced Women

FATA-Federally Administered Tribal Areas

CEDAW-Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

SPSS-Statistical Package for Social Sciences

ERC-Ethical Review Committee

PTSD-Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

ASD-Acute Stress Disorder

KP-Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

DSM IV-Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS

HMK led the study concept and design, data analysis, drafting of the manuscript, and participated in the data collection. KSK and AWY participated in developing the study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data and review of the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

AUTHOR’S INFORMATION

HMK is currently working as a Technical Advisor Health at The FATA Development Programme, GIZ, Pakistan. KSK is an Associate Professor at the Department of Community Health Sciences, The Aga Khan University Karachi, Pakistan. AWY is a Consultant at the Department of Psychiatry, Shifa International Hospital Islamabad, Pakistan.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank all the respondents who participated in this study and gave their precious times to the study. We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of the members of the data collection teams as well as the administration of the IDP camps at Kacha Ghari Peshawar for their cooperation and are also thankful to the district administration of Peshawar for their permission to conduct the study in Peshawar.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in the article reflect the personal opinion of the authors, not of their organizations.

REFERENCES

- Meyer S (2013) UNHCR’s mental health and psychosocial support for Persons of Concern. Global Review - 2013, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Armiya’u AY, Obembe A, Audu MD, Afolaranmi TO (2013) Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among inmates in Jos maximum security prison. Open Journal of Psychiatry 3: 12-17.

- Guajardo MGU, Slewa-Younan S, Smith M, Eagar S, Stone G (2016) Psychological distress is influenced by length of stay in resettled Iraqi refugees in Australia. Int J Ment Health Syst 10.

- Guajardo MGU, Slewa-Younan S, Santalucia Y, Jorm AF ( 2016) Important considerations when providing mental health first aid to Iraqi refugees in Australia: a Delphi study. Int J Ment Health Syst 10.

- UNHCR (2012) The state of the World’s Refugees - In Search of Solidarity. In: Kumin J (eds.). UNCHR, Geneva, Switzerland.

- The Irish Consortium (2015) Women, War and Displacement: A review of the impact of conflict and displacement on gender-based violence: A report by The Irish Consortium on Gender-Based Violence. The Irish Consortium, Ireland, UK.

- Stewart MJ, Makwarimba E, Beiser M, Neufeld A, Simich L, et al. (2010) Social support and health: immigrants’ and refugees’ perspectives. Diversity & Health and Care.

- Alemi Q, James S, Cruz R, Zepeda V, Racadio M (2014) Psychological distress in afghan refugees: a mixed-method systematic review. J Immigr Minor Health 16: 1247-1261.

- The Camp Management Toolkit (2008) Norwegian Refugee Council. The Camp Management Toolkit, Oslo, Norway.

- Ramazanov R, RA, Allahverdiyev I, Abdullahyeva L (2006) The Status of IDP Women in Azerbaijan - A Rapid Assessment. United Nations Development Fund for Women, Baku, Azerbaijan.

- UNHCR ( 2006) The State of the world`s Refugees. Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

- Brookings Institution (2008) Protecting Internally Displaced Persons: A Manual for Law and Policymakers. Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Brookings (2005) Addressing Internal Displacement: A Framework for National Responsibility, Brookings, Washington, D.C., USA.

- United Nations (1948) Universal Declaration of Human Rights. United Nations, New York, USA.

- Thomas SL, Thomas SD (2004) Displacement and Health. Br Med Bull 69: 115-127.

- Roberts B, Ocaka KF, Browne J, Oyok T, Sondorp E (2008) Factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder and depression amongst internally displaced persons in northern Uganda. BMC Psychiatry 8.

- Thomas SL, Thomas SD (2004) Displacement and Health. Br Med Bull 69: 115-127.

- Roberts B, Ocaka KF, Browne J, Oyok T, Sondorp E (2008) Factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder and depression amongst internally displaced persons in northern Uganda. BMC Psychiatry 8.

- Glen Kim, Torbay R, Lawry L (2007) Basic health, women's health, and mental health among internally displaced persons in Nyala Province, South Darfur, Sudan. Am J Public Health 97: 353-361.

- Roberts B, Ocaka KF, Browne J, Oyok T, Sondrop E (2009) Factors associated with the health status of internally displaced persons in northern Uganda. J Epidemiol Community Health 63: 227-232.

- Catani C, Jacob N, Schauer E, Kohila M, Neuner F (2008) Family violence, war, and natural disasters: a study of the effect of extreme stress on children’s mental health in Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry 8.

- Lersner UV, Elbert T, Neuner F (2008) Mental health of refugees following state-sponsored repatriation from Germany. BMC Psychiatry 8.

- Roberts B, Damundu EY, Lomoro O, Sondorp E (2009) Post-conflict mental health needs: a cross-sectional survey of trauma, depression and associated factors in Juba, Southern Sudan. BMC Psychiatry 9.

- Mills EJ, Singh S, Holtz TH, Chase RM, Dolma S (2005) Prevalence of mental disorders and torture among Tibetan refugees: A systematic review. BMC International Health and Human Rights 5.

- Nelson BD, Fernandez WG, Galea S, Sisco S, Dierberg K, et al. (2004) War-related psychological sequelae among emergency department patients in the former Republic of Yugoslavia. BMC Medicine 2.

- de Jong K, de Kam SV, Ford N, Lokuge K, Fromm S, et al. (2008) Conflict in the Indian Kashmir Valley II: psychosocial impact. Confl Health 2.

- Onyut LP, Neuner F, Ertl V, Schauer E, Odenwald M, et al. (2009) Trauma, poverty and mental health among Somali and Rwandese refugees living in an African refugee settlement - an epidemiological study. Confl Health 3.

- Carballo M, Smajkic A, Zeric D, Dzidowska M, Gebre-Medhin J, et al. (2004) Mental health and coping in a war situation: the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina. J Biosoc Sci 36: 463-477.

- Mills MA, Edmondson D, Park CL (2007) Trauma and Stress Response Among Hurricane Katrina Evacuees. Am J Public Health 97: 116-123.

- ProrokovicA, Cavka M, Adoric VC (2005) Psychosomatic and depressive symptoms in civilians, refugees, and soldiers: 1993-2004 longitudinal study in Croatia. Croat Med J 46: 275-281.

- Math SB, John JP, Girimaji SC, Benegal V, Sunny B, et al. (2008) Comparative study of psychiatric morbidity among the displaced and non-displaced populations in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands following the tsunami. Prehosp Disaster Med 23: 29-34.

- Roth G (2006) A prospective study of mental health among mass-evacuated Kosovo Albanians. Karolinska University Press, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Murthy SR, Lakshminarayana R (2006) Mental health consequences of war: a brief review of research findings. World Psychiatry 5: 25-30.

- Buscher D (2006) Displaced women and girls at risk: Risk factors, protection, solutions and resource tools. Women’s Commission for Refugee Women & Children, New York, USA.

- Almedom A, Tesfamichael B, Mohammed Z, Mascie-Taylor N, Muller J, et al. (2005) Prolonged displacement may compromise resilience in Eritrean mothers. Afr Health Sci 5: 310-314.

- Glatz AK (2015) Pakistan: solutions to displacement elusive for both new and protracted IDPs. Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, Geneva, Switzerland.

- UN Women (1979) The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. UN Women, New York, USA.

- UN Women (2005) Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. Combined initial, second and third periodic reports. UN Women, New York, USA.

- UN (2007) List of issues and questions with regard to the consideration of an initial and periodic report: Pakistan. United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, New York, USA.

- UN (2007) Responses to the list of issues and questions for consideration of the combined initial, second and third periodic report of Pakistan: Pakistan. The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, New York, USA.

- UN (2007) Concluding comments of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, New York, USA.

- UNOCHA (2004) Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. UNOCHA, Geneva, Switzerland.

- UN (2008) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly: 62/153. Protection of and assistance to internally displaced persons, UN, New York, USA.

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie J (2004) Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educational Researcher 33: 14-26.

- Hanson WE, Creswell JW, Clark VLP, Petska KS, Creswell JD (2005) Mixed Methods Research Designs in Counseling Psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology 52: 224-235.

- Creswell JW, Clark VLP, Gutmann ML, Hanson WE (2003) Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. Teddlie C, Tashakkori A (eds.). Sage Publications, California, USA.

- Ivankova NV, Creswell JW, Stick Sl (2006) Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice. Field Methods 18: 3-20.

- Jackson C (2007) The General Health Questionnaire. Occupational Medicine 57.

- de Jong K, van der Kam S, Ford N, Hargreaves S, van Oosten R, et al. (2007) The trauma of ongoing conflict and displacement in Chechnya: quantitative assessment of living conditions, and psychosocial and general health status among war displaced in Chechnya and Ingushetia. Confl Health 1.

- Nagyova I, Krol B, Szilasiova A, Stewart R, van Dijk JP, van den Heuvel WJA, et al. (2000) General Health Questionnaire-28: Psychometric Evaluation of the Slovak Version. Studia Psychologica 42: 351-361.

- Riaz H, Reza H (1998) The evaluation of an Urdu version of the GHQ-28. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 97: 427-432.

- Mack N, Woodsong C, MacQueen KM, Guest G, Namey Emily (2005) Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector’s Field Guide. Family Health International, North Carolina, USA.

- Ulin PR (2002) Qualitative Methods: A Field Guide for Applied Research in Sexual and Reproductive Health. Family Health International, North Carolina, USA.

- Collins KMT, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Jiao QG (2007) A Mixed Methods Investigation of Mixed Methods Sampling Designs in Social and Health Science Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1.

- Teddlie C, Yu F, Teddlie C (2007) Mixed Methods Sampling: A Typology with Examples. Journal of Mixed Methods Research1: 77-100.

- Manchanda R (2004) Gender Conflict and Displacement: Contesting 'Infantilisation' of Forced Migrant Women. Economic and Political Weekly 39: 4179-4186.

- Noorbala AA, Bagheri Yazdi SA, Yasamy MT, Mohammad K (2004) Mental health survey of the adult population in Iran. Br J Psychiatr 184: 70-73.

- Solomon Z (1988) Somatic complaints, stress reaction, and posttraumatic stress disorder: a three-year follow-up study. Behav Med 14: 179-185.

- Warshaw MG, Fierman E, Pratt L, Hunt M, Yonkers KA, et al. (1993) Quality of life and dissociation in anxiety disorder patients with histories of trauma or PTSD. Am J Psychiat 150: 1512-1516.

- Lie B, Lavik NJ, Laake P (2001) Traumatic events and psychological symptoms in a non-clinical refugee population. Journal of Refugee Studies 14: 276-294.

- Thoms ONT, Ron J (2007) Public health, conflict and human rights: toward a collaborative research agenda. Confl Health 1.

- Cardozo BL, Vergara A, Agani F, Gotway CA (2000) Mental health, social functioning, and attitudes of Kosovar Albanians following the war in Kosovo. JAMA 284: 569-577.

- KR (1997) Psychobiology and clinical management of posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Boer D, Dekker M (eds.). Clinical management of anxiety: Theory and practical applications. Marcel Dekker, New York, USA.

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB (1995) Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52: 1048-1060.

- Perkonigg A, Kessler RC, Storz S, Wittchen H-U (2000) Traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: prevalence, risk factors and comorbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand 101: 46-59.

- Checchi F, Gayer M , Grais RF, Mills EJ (2007) Public health in crisis-affected populations: A practical guide for decision-makers. Overseas Development Institute, London, UK.

- Mullany LC, Richards AK, Lee CI, Suwanvanichkij V, Maung C, et al. (2007) Population-based survey methods to quantify associations between human rights violations and health outcomes among internally displaced persons in eastern Burma. J Epidemiol Community Health 61: 908-914.

Citation: Khan HM, Khan KS, Yousafzai AW (2017) A Sequential Explanatory Mixed Method Study to Identify Human Rights Violations and Asses the Psychosocial Health Status of the Internally Displaced Women of North-West Pakistan. J Community Med Public Health Care 4: 027.

Copyright: © 2017 Hassan Mehmood Khan, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.