Alloreactive Natural Killer Cells Have Anti-Tumor Capacity Against Disseminated Human Multiple Myeloma in Rag2-/-C-/-Mice When Combined with Low Dose Cyclophosphamide and Total Body Irradiation

*Corresponding Author(s):

Gerard MJ BosDepartment Of Internal Medicine, Division Of Hematology, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, Netherlands

Tel:+31 433877026,

Fax:+31 433875006

Email:Gerard.Bos@mumc.nl

Abstract

Immunotherapy with alloreactive Natural Killer (NK) cells could be a new treatment option for the incurable plasma cell malignancy Multiple Myeloma (MM). In the present study, we explored the anti-MM potential of alloreactive NK cells using theRAG2-/-γc-/-immunodeficient disseminated mouse model. In this model, we studied NK cell-mediated Graft versus MM (GvM) responses while concurrently examining the risk of developing Graft versus Host Disease (GvHD). First, luciferase expressing human U266 MM cells were intravenously (i.v.) injected in RAG2-/-γc-/- mice, and human KIR-ligand alloreactive NK cells or PBMC were injected (i.v.) after Bioluminescent Imaging (BLI)-confirmed tumor formation. BLI of tumor growth kinetics in a preliminary experiment revealed that infusion of resting NK cells decreased MM burden in one out of four treated mice receiving 3 injections of 8x106 NK cells, with no signs of GvHD. Although infused PBMCs efficiently eradicated established MM in all treated mice, this concurrently induced lethal GvHD. rhIL-2 activated NK cells, injected in subcutaneously (s.c.) growing MM tumors, proved to be superior to resting NK cells and anti-MM responses occurred NK cell dose dependently. Since MM is a dispersed malignancy spread throughout the body, we investigated the therapeutic potential of rhIL-2 activated NK cells, from either cord blood or peripheral blood origin, in the disseminated MM mouse model. Whereas activated NK cells were unable to trigger efficient GvM responses when given alone, the infusion of activated NK cells following a non-curative conditioning treatment with cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation, did prolong progression free survival (p=0.003) without any signs of GvHD. This study illustrates the therapeutic potential and safety of NK cell therapy in MM and is an important step towards cell-based immunotherapy for MM patients. It also establishes the RAG2-/-γc-/- MM model as a clinically relevant pre-clinical model to further develop NK cell immunotherapy.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Multiple Myeloma (MM) is a hematological malignancy characterized by clonal expansion of plasma cells in the bone marrow [1]. Despite new options, state-of-the-art treatment results only in a median survival of 5-7 years [2]. New treatment strategies with curative potential with reduced toxicity are therefore urgently needed. Autologous-Stem Cell Transplantation (auto-SCT) combined with high dose chemotherapy has improved overall survival when compared to treatment with conventional chemotherapy alone; still the great majority of patients eventually relapse [3]. Allogeneic-SCT (allo-SCT) has the potential to cure MM by the so-called graft versus tumor response of donor immune cells. However, an important drawback of allo-SCT is the high risk of life-threatening Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD) mediated by donor T cells responding to mismatched histocompatibility antigens [4,5]. Moreover, treatment related mortality after allo-SCT is high, and patients surviving the procedure still show progression of disease in the majority of cases.

When allo-SCT is performed over HLA barriers, both Natural Killer (NK) cells and T cells can mediate GvM responses, but an important advantage of NK cells is that they do not seem to mediate GvHD [6]. NK cells are capable of targeting virally infected or malignantly transformed cells and become activated by tilting the delicate balance of inhibitory and activating receptor signals [7]. An important class of inhibitory receptors is the Killer Immunoglobulin-like Receptor (KIR) family interacting with the highly polymorphic HLA class I molecules expressed by virtually every healthy cell. The most important inhibitory KIRs are KIR3DL1 that binds HLA-Bw4 epitopes, KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 that interact with HLA-group C1 alleles and KIR2DL1 that binds HLA-group C2 alleles [8-10]. Upon engagement of inhibitory KIRs with the HLA class I molecules of a target cell, suppressive signals are transmitted, prohibiting NK cells to kill the target cell. This mechanism of self-recognition can be used in anti-tumor therapy, by transplantation of NK cells with a licensed KIR repertoire that mismatches for the donor HLA according to the “missing self” principle [11,12]. Ruggeri et al., showed that the anti-tumor effect KIR-mismatched haplo-identical SCT setting in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) is attributed to the presence of “alloreactive NK cells” [6]. AML patients treated with a KIR-ligand mismatched allogeneic bone marrow transplant show increased survival over patients transplanted without such a mismatch [13].

There is accumulating evidence to support a role for NK cells in controlling the progression of MM [14-20]. Therapeutic interventions like lenalidomide and thalidomide increase NK cell reactivity and thereby improve survival. Additionally, there is evidence that alloreactive NK cells may be relevant in MM. In a group of 10 patients with MM that were treated with alloreactive NK cells, fifty percent demonstrated a response, with some patients having a complete remission [18]. Recently, these authors expanded their observations in more patients, showing that freshly prepared NK cells could continue to expand in vivoafter infusion, but only in two of eight patients a clinical response could be attributed to the infused NK cells [19]. Kroger et al., analyzed patients that were transplanted with an unrelated donor, which included donors with a mismatch for HLA?C groups, thereby allowing NK cell alloreactivity. The group of patients that received a transplant with the alloreactive NK cells indeed showed a far lower incidence of disease recurrence [21].

Unfortunately, since MM is a disease of the elderly, the majority of MM patients is not eligible for KIR mismatched haplo-identical SCT due to the severe conditioning regime and transplantation related complications and thus indicating that other modalities have to be developed. Our previous research lead us to the idea that infusion of only KIR-ligand mismatched NK cells is an interesting treatment option to provide curative effects that bypasses the risks that are associated with a full HLA mismatched allo-SCT. in vitro, NK cells have been shown to efficiently kill MM cells [16,17]. Recently, we showed that KIR-ligand mismatched NK cells are better in doing this than matched cells [22]. We could demonstrate that it is also possible to kill MM cells under hypoxia, which is an immunosuppressive condition relevant in this disease [23]. Before performing clinical trials, immunodeficient mouse models provide an excellent opportunity to test novel treatment strategies. The RAG2-/-γc-/-MM mouse model was originally developed by some of us to study GvHD development after injection of PBMCs or purified T cells [24]. In this model, we previously showed that human PBMC xenografts did not only induce GvHD but also GvM [25]. In the present study, we used thisRAG2-/-γc-/-MM mouse model to obtain the proof of concept for the effect of alloreactive KIR-ligand mismatched NK cells on GvM and GvHD in MM bearing mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and cell cultures

| Cell line | HLA genotype |

| U266 | C1+ C2- Bw4- |

| L363 | C1+ C2- Bw4- |

| LME-1 | C1+ C2- Bw4- |

| UM-9 | C1+ C2- Bw4- |

| RPMI-8226/s | C1+ C2+ Bw4- |

| OPM-1 | C1+ C2+ Bw4- |

| XG-1 | C1+ C2+ Bw4+ |

Table 1: Matched and mismatched KIRs based on genotypic expression of HLA epitopes. Genotypic expression of HLA-class I epitopes as determined by luminex-SSO.

Mice

Generation of Multiple Myeloma (MM) RAG2−/−γc−/−mice

Preparation and transplantation of human PBMCs and peripheral blood derived NK cells

Flow cytometry

NK cell Cytotoxicity assay

Statistics

RESULTS

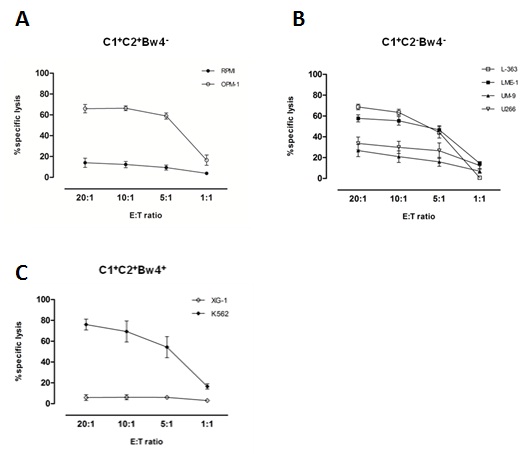

Alloreactive NK cells kill MM cell lines in vitro

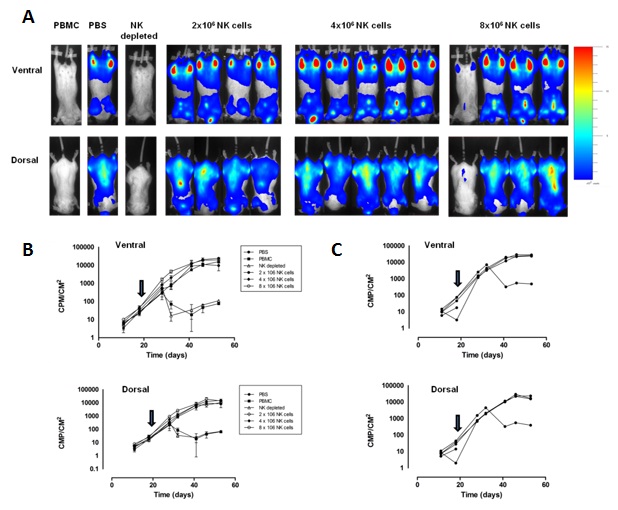

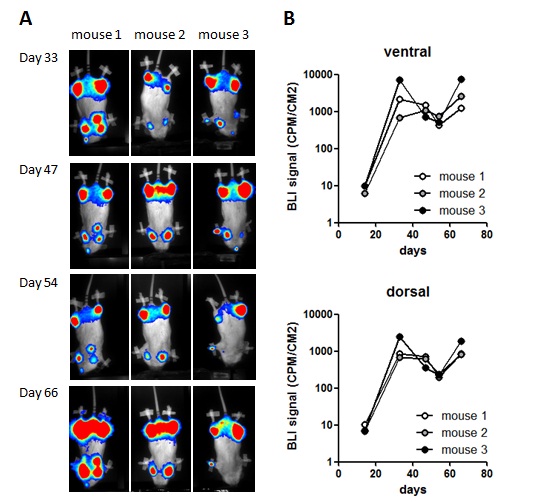

Freshly isolated, resting alloreactive NK cells can mediate anti-MM effects in vivo

IL-2 activated NK cells mediate anti-MM responses in a dose dependent manner in vivo

The above-mentioned data demonstrated that the effect of IL-2 activated NK cells occurred in a dose dependent manner. To investigate whether IL-2 activated NK cells could eliminate established MM in vivoas well, mice were s.c. injected with either 0.3x106, 1x106, 3x106 or 9x106 U266 cells. Upon development of a s.c.tumor on day 13, IL-2 activated NK cells were injected intratumorally. In the two groups receiving the highest number of U266 cells (3x106 or 9x106 cells), NK cell injection did not reduce the tumor load (Figure 3B). However, in the two groups receiving the lowest number of U266 cells (0.3x106 or 1x106cells) a reduction in the BLI signal could be observed after NK cell injection. Together these data demonstrate that IL-2 activated NK cells can mediate anti-MM responses in vivo but that the effector to target ratio is very important for in vivo responses.

IL-2 activated human NK cells can home to the bone marrow of MM bearing RAG2-/-γc-/- mice

Cyclophosphamide (cyclo)/Total Body Irradiation (TBI) treatment alone does not cure disseminated MM

B) Graph shows BLI signal per mouse on the indicated days.

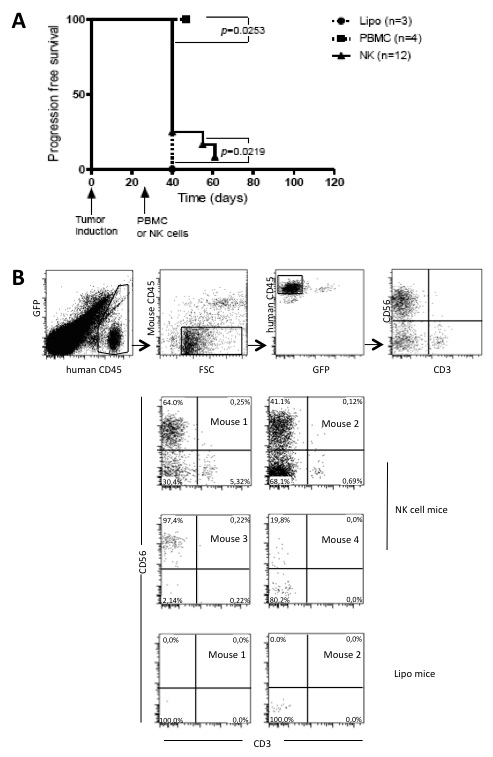

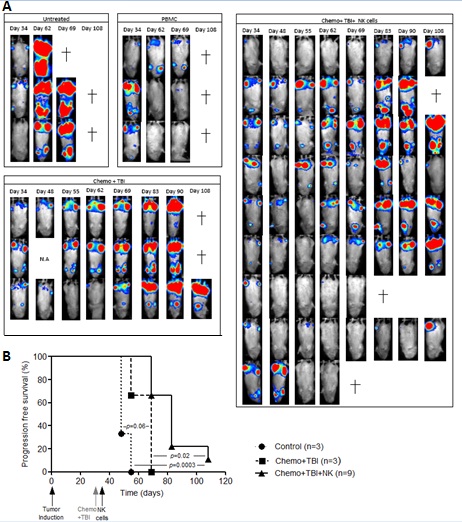

Combination treatment with cyclo/TBI and IL-2 activated NK cells can provide anti-MM responses in the disseminated MM model

DISCUSSION

Despite novel treatment options in the last decade, MM remains largely incurable illustrating the need to develop novel therapeutic treatment options. In the present proof-of-concept study, we investigated the effect of alloreactive KIR-ligand mismatched NK cells on GvM and GvHD in the RAG2-/-γc-/- mouse MM model. This revealed that IL-2 activated NK cells in combination with low dose conditioning with cyclo/TBI can mediate anti-MM responses. Importantly, we did not observe a single sign of GvHD in any of the experimental treatment protocols upon NK cell injection. In line with these data, a first clinical study in MM showed that KIR-ligand mismatched NK cells could be infused into MM patients without causing toxicity and GvHD [18] and comparable observations have been made in AML. Altogether, this illustrates the feasibility and clinical potential of the approach.

Thus far, the clinical efficacy of NK cell infusion in cancer patients has been somewhat inconsistent emphasizing that optimization of therapeutic protocols is required [30]. NK cells can kill only a limited number of target cells. In the current study, we observed that NK cell responses against s.c. MM occurred in a NK cell dose dependent manner (Figure 3) and with unactivated, resting NK cells, we possibly observed a biological effect of NK cells in one of the four mice (25%) with disseminated MM in the group receiving the highest NK cell dose (Figure 2). Dose dependency has also been shown in the 5T33M MM model were the anti-MM response of transplanted mouse NK cells could be enhanced by infusion of a higher number of NK cells [31]. In another study, with human NK cells expanded on K562-mb15-41BBL feeder cells, adoptive transfer of 160x106 NK cells inhibited growth of OPM2 while transfer of 40x106 NK cells was not sufficient [32]. These data suggest that infusion of really high numbers of NK cells are needed to improve clinical efficacy of NK cell therapy. Numbers that can be obtained using a bioreactor (our unpublished data).

In our model, mice having established MM were treated with NK cells. In that way, our model resembles the clinical situation were plasma cells are dispersed over multiple sites encompassing the entire skeletal system. Because of this high tumor load, a major caveat is the number of NK cells required for clinically effective therapy that can be obtained by isolation from peripheral blood. Ex vivo expanded NK cells could provide a solution and are an interesting alternative for NK cells derived from apheresis products. An additional advantage is that the ex vivo culturing period would allow for extra NK cell activation. In the current study, we used two sources of NK cells; IL-2 activated NK cells isolated from blood of healthy individuals and NK cells that were generated and expanded from cord blood [26,27]. With both sources we observed reactivity against established, disseminated MM in combination with chemo/TBI (Figure 6). This is in line with two previous studies showing that NK cells expanded on K562-mb15-41BBL feeder cells [32] and the NK cell lines NK-92 or KHYG-1 [33] reduced disease burden in vivo (in mouse models for MM),together demonstrating that different sources of NK cells could be further tested for clinical application.

In the current study, NK cell donors were selected based on the genotypic presence of a mismatch between inhibitory KIRs on the NK cells and the HLA epitopes on the U266 cell line. Phenotypically, however, the infused NK cell population was heterogeneous because NK cells express one or a combination of inhibitory receptors on their cell surface hence leading to different NK cells subsets; i.e., subsets exclusively expressing KIRs mismatched with the HLA ligands present on U266 target cells, subsets exclusively expressing KIRs matched with the ligands and subsets expressing both types of KIRs. Therefore, only a small percentage of the infused NK cells exclusively expressed KIRs mismatched with the U266 HLA ligand (HLA-C1) and the majority of NK cells (co-)expressed NKG2A. We recently showed, that in vitro KIR-ligand mismatched NK cells are more effective than matched NK cells in mediating myeloma cell killing [22]. In addition, we demonstrated that U266 cells in this disseminated MM model expressed HLA-E at a level that is sufficient to inhibit NKG2A expressing NK cells [22]. Based on these data, NK cells expressing mismatched KIRs and lacking expression of matched KIRs or NKG2A could be expected to be the most potent effector cells against MM in vivo as well. Future experiments with HLA-E gene knock-down in U266-luc cells in the RAG2-/-γc-/-mice might enable us to determine the efficacy-blocking effect of HLA-E expression in NK cell therapy. Ruggeri et al., have demonstrated that, in an AML mouse model, indeed the mismatched NK cells mediated in vivo anti-tumor effects while matched NK cells did not [6]. Therefore, it is highly relevant to study whether KIR-ligand mismatched NK cells are indeed more potent against MM in vivo because acquiring high enough numbers of these subsets for clinical application will be challenging and it is probably worthwhile to develop strategies to promote expansion or development of NK cell subsets with the highest anti-MM reactivity.

Our data show that U266 cells are sensitive for NK cell killing in vitro (Figure 1) while in vivo these cells seemed to be more difficult to eliminate (Figure 2). An explanatory factor could be that only a fraction of the NK cells actually homes to the bone marrow resulting in a less favorable E:T ratio as compared to in vitro. Phenotypic analysis of bone marrow biopsies at the time of sacrifice of the mice revealed that activated NK cells derived from peripheral blood and cord blood indeed can home to the site of tumor location in our model (Figure 4). This is in line with a previous study showing that cord blood derived NK cells migrate to the bone marrow of NSG mice and functionally express CXCR4 [28], a chemokine receptor described to be important for homing to the bone marrow [34], and with the observation that primary blood derived NK cells express CXCR4 [35]. In addition to NK cells, we observed some T cells (huCD45+CD3+CD56-) and human leukocytes that were neither NK cells nor T cells (huCD45+CD3-CD56-) in mice receiving NK cells from peripheral blood. Presumably this was the result of the minor impurity of the peripheral blood derived NK cell product. Although, in principle contaminating T cells in the peripheral blood product can mediate an anti-MM activity as well, the actual numbers of T cells contaminating our cell preparations were not sufficient to explain the anti-MM response. To induce a xenogeneic GvHD response with infused PBMC cells at least 6x106 T cells are required in pre-conditioned mice (TBI + toxic liposomes) [25]. In the experiment where we combined cyclo/TBI and NK cell treatment, we did not observe any human lymphocytes in the bone marrow at the time of sacrifice, which presumably was due to the longer follow-up period 108 days vs 60 days in the experiment with activated NK cells without cyclo/TBI.

In the RAG2-/-γc-/-model, MM cells grow in their natural environment, i.e., the bone marrow, making it an excellent model for preclinical testing of immunotherapy reflecting MM pathophysiology. This is important because it is exactly this environment that, through the presence of factors like hypoxia [23] and stromal cells [36], or soluble factors like PGE2 [37] can suppress development of effective anti-tumor immunity making it extremely important to test the anti-MM capacity of NK cells in such relevant models. An interesting other preclinical model recently developed by members of our group is a scaffold-based model where patient derived MM cells grow on s.c. implanted scaffolds [38]. In such a model, it would be highly interesting to address the synergistic potential of a combination of approaches targeting immunosuppressive bone marrow associated factors with alloreactive NK cell therapy to achieve maximal efficiency of the response. One such approach can be the combination of chemo/radiotherapy and activated NK cells that, in our study, resulted in a better anti-MM response as compared to treatment with activated NK cells alone. Here, we did not study the mechanism by which the conditioning regime enhanced NK cell functioning but, several previous studies demonstrated that either chemo or radiotherapy could render tumor cells more susceptible for NK cells by up regulation of activating ligands [39-41]. It can be hypothesized that donor dendritic cells are killed by the host NK cells, thus a T cell mediated GvHD cannot be induced [42]. On the other hand, the conditioning treatment could trigger the release of NK cell promoting cytokines such as IL-2, IL-15 and IL-21 [43] or promote recruitment or survival of the NK cells at the tumor site [44,45]. Also, it would be interesting to combine the immunomodulatory drug Pomalidomide or ADCC triggering agents such as Elotuzumab to boost the NK cell activity in this model.

In the current proof-of-concept study, we showed the biological potential of alloreactive NK cells against disseminated MM. In addition, we demonstrated that IL-2 activated NK cells can home to the bone marrow of MM bearing mice and that anti-MM responses occurred in a dose dependent manner. The latter suggests that infusion of a higher number of alloreactive NK cells can help to improve clinical efficacy and those patients should, preferably, be treated in remission or at least with low residual disease. Our data also demonstrate that combination therapy of alloreactive NK cells and chemo/radiotherapy could help to improve the anti-MM effect. The RAG2-/-γc-/- mouse MM is a pathophysiologically relevant model to further develop and optimize NK cell treatment protocols and to test ex vivo expanded/activated NK cells ultimately leading to enhanced clinical efficacy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The RAG2-/-γc-/- mice were originally obtained from the Amsterdam Medical Center (AMC, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The myeloma cell line LME-1 was kind gift from Dr. R. van Oers, AMC, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. The authors would like to thank the tissue-typing laboratory (MUMC+) for HLA typing of the cell lines. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Dirk Groenewegen and Dr. Jan Spanholz (Glycostem technologies, Nijmegen) and Dr. Harry Dolstra (Radboud UMC) for providing cord blood derived NK cells. The authors would also like to thank Regina de Jong-Korlaar and Frans Hofhuis (Department of Cell Biology, University Medical Center Utrecht) for their technical assistance with animal studies. L. Wieten was supported by a personal grant from Dutch Cancer association (KWF Kankerbestrijding; UM2012-5375). G. Bos, M. van Gelder and L. Wieten were supported by a grant from the Kankeronderzoeksfonds Limburg.

REFERENCES

- Raab MS, Podar K, Breitkreutz I, Richardson PG, Anderson KC (2009) Multiple myeloma. Lancet 374: 324-339.

- Palumbo A, Anderson K (2011) Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 364: 1046-1060.

- Bensinger WI (2009) Role of autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantation in myeloma. Leukemia 23: 442-448.

- Lokhorst HM, Schattenberg A, Cornelissen JJ, Thomas LL, Verdonck LF (1997) Donor leukocyte infusions are effective in relapsed multiple myeloma after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood 90: 4206-4211.

- Shlomchik WD (2007) Graft-versus-host disease. Nat Rev Immunol 7: 340-352.

- Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, Perruccio K, Shlomchik WD, et al. (2002) Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science 295: 2097-2100.

- Vivier E, Ugolini S, Blaise D, Chabannon C, Brossay L (2012) Targeting natural killer cells and natural killer T cells in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 12: 239-252.

- Colonna M, Borsellino G, Falco M, Ferrara GB, Strominger JL (1993) HLA-C is the inhibitory ligand that determines dominant resistance to lysis by NK1- and NK2-specific natural killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 12000-12004.

- Moretta L, Locatelli F, Pende D, Marcenaro E, Mingari MC, et al. (2011) Killer Ig-like receptor-mediated control of natural killer cell alloreactivity in haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 117: 764-771.

- Parham P (2005) MHC class I molecules and KIRs in human history, health and survival. Nat Rev Immunol 5: 201-214.

- Jonsson AH, Yokoyama WM (2009) Natural killer cell tolerance licensing and other mechanisms. Adv Immunol 101: 27-79.

- Kim S, Poursine-Laurent J, Truscott SM, Lybarger L, Song YJ, et al. (2005) Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature 436: 709-713.

- Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Capanni M, Urbani E, Carotti A, et al. (2007) Donor natural killer cell allorecognition of missing self in haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: challenging its predictive value. Blood 110: 433-440.

- Osterborg A, Nilsson B, Björkholm M, Holm G, Mellstedt H (1990) Natural killer cell activity in monoclonal gammopathies: relation to disease activity. Eur J Haematol 45: 153-157.

- Frohn C, Höppner M, Schlenke P, Kirchner H, Koritke P, et al. (2002) Anti-myeloma activity of natural killer lymphocytes. Br J Haematol 119: 660-664.

- Carbone E, Neri P, Mesuraca M, Fulciniti MT, Otsuki T, et al. (2005) HLA class I, NKG2D, and natural cytotoxicity receptors regulate multiple myeloma cell recognition by natural killer cells. Blood 105: 251-258.

- El-Sherbiny YM, Meade JL, Holmes TD, McGonagle D, Mackie SL, et al. (2007) The requirement for DNAM-1, NKG2D, and NKp46 in the natural killer cell-mediated killing of myeloma cells. Cancer Res 67: 8444-8449.

- Shi J, Tricot G, Szmania S, Rosen N, Garg TK (2008) Infusion of haplo-identical killer immunoglobulin-like receptor ligand mismatched NK cells for relapsed myeloma in the setting of autologous stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol 143: 641-53.

- Szmania S, Lapteva N, Garg T, Greenway A, Lingo J, et al. (2015) Ex vivo-expanded natural killer cells demonstrate robust proliferation in vivo in high-risk relapsed multiple myeloma patients. J Immunother 38: 24-36.

- Katodritou E, Terpos E, North J, Kottaridis P, Verrou E, et al. (2011) Tumor-primed natural killer cells from patients with multiple myeloma lyse autologous, NK-resistant, bone marrow-derived malignant plasma cells. Am J Hematol 86: 967-973.

- Kröger N, Shaw B, Iacobelli S, Zabelina T, Peggs K, et al. (2005) Comparison between antithymocyte globulin and alemtuzumab and the possible impact of KIR-ligand mismatch after dose-reduced conditioning and unrelated stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol 129: 631-643.

- Sarkar S, van Gelder M, Noort W, Xu Y, Rouschop KM, et al. (2015) Optimal selection of natural killer cells to kill myeloma: the role of HLA-E and NKG2A. Cancer Immunol Immunother 64: 951-963.

- Sarkar S, Germeraad WT, Rouschop KM, Steeghs EM, van Gelder M, et al. (2013) Hypoxia induced impairment of NK cell cytotoxicity against multiple myeloma can be overcome by IL-2 activation of the NK cells. PLoS One 8: 64835.

- van Rijn RS, Simonetti ER, Hagenbeek A, Hogenes MC, de Weger RA (2003) A new xenograft model for graft-versus-host disease by intravenous transfer of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in RAG2-/- gammac-/- double-mutant mice. Blood 102: 2522-2531.

- Rozemuller H, van der Spek E, Bogers-Boer LH, Zwart MC, Verweij V, et al. (2008) A bioluminescence imaging based in vivo model for preclinical testing of novel cellular immunotherapy strategies to improve the graft-versus-myeloma effect. Haematologica 93: 1049-1057.

- Spanholtz J, Preijers F, Tordoir M, Trilsbeek C, Paardekooper J, et al. (2011) Clinical-grade generation of active NK cells from cord blood hematopoietic progenitor cells for immunotherapy using a closed-system culture process. PLoS One 6: 20740.

- Spanholtz J, Tordoir M, Eissens D, Preijers F, van der Meer A, et al. (2010) High log-scale expansion of functional human natural killer cells from umbilical cord blood CD34-positive cells for adoptive cancer immunotherapy. PLoS One 5: 9221.

- Cany J, van der Waart AB, Tordoir M, Franssen GM, Hangalapura BN, et al. (2013) Natural killer cells generated from cord blood hematopoietic progenitor cells efficiently target bone marrow-residing human leukemia cells in NOD/SCID/IL2Rg (null) mice. PLoS One 8: 64384.

- Frings PW, Van Elssen CH, Wieten L, Matos C, Hupperets PS, et al. (2011) Elimination of the chemotherapy resistant subpopulation of 4T1 mouse breast cancer by haploidentical NK cells cures the vast majority of mice. Breast Cancer Res Treat 130: 773-781.

- Sutlu T, Alici E (2009) Natural killer cell-based immunotherapy in cancer: current insights and future prospects. J Intern Med 266: 154-181.

- Alici E, Konstantinidis KV, Sutlu T, Aints A, Gahrton G, et al. (2007) Anti-myeloma activity of endogenous and adoptively transferred activated natural killer cells in experimental multiple myeloma model. Exp Hematol 35: 1839-1846.

- Garg TK, Szmania SM, Khan JA, Hoering A, Malbrough PA, et al. (2012) Highly activated and expanded natural killer cells for multiple myeloma immunotherapy. Haematologica 97: 1348-1356.

- Swift BE, Williams BA, Kosaka Y, Wang XH, Medin JA (2012) Natural killer cell lines preferentially kill clonogenic multiple myeloma cells and decrease myeloma engraftment in a bioluminescent xenograft mouse model. Haematologica 97: 1020-1028.

- Beider K, Nagler A, Wald O, Franitza S, Dagan-Berger M, et al. (2003) Involvement of CXCR4 and IL-2 in the homing and retention of human NK and NK T cells to the bone marrow and spleen of NOD/SCID mice. Blood 102: 1951-1958.

- Inngjerdingen M, Damaj B, Maghazachi AA (2001) Expression and regulation of chemokine receptors in human natural killer cells. Blood 97: 367-375.

- McMillin DW, Delmore J, Negri JM, Vanneman M, Koyama S, et al. (2012) Compartment-Specific Bioluminescence Imaging platform for the high-throughput evaluation of antitumor immune function. Blood 119: 131-138.

- Van Elssen CH, Vanderlocht J, Oth T, Senden-Gijsbers BL, Germeraad WT, et al. (2011) Inflammation-restraining effects of prostaglandin E2 on Natural Killer-Dendritic Cell (NK-DC) interaction are imprinted during DC maturation. Blood 118: 2473-2482.

- Groen RW, Noort WA, Raymakers RA, Prins HJ, Aalders L, et al. (2012) Reconstructing the human hematopoietic niche in immunodeficient mice: opportunities for studying primary multiple myeloma. Blood 120: 9-16.

- Fionda C, Soriani A, Malgarini G, Iannitto ML, Santoni A, et al. (2009) Heat shock protein-90 inhibitors increase MHC class I-related chain A and B ligand expression on multiple myeloma cells and their ability to trigger NK cell degranulation. J Immunol 183: 4385-4394.

- Shi J, Tricot GJ, Garg TK, Malaviarachchi PA, Szmania SM, et al. (2008) Bortezomib down-regulates the cell-surface expression of HLA class I and enhances natural killer cell-mediated lysis of myeloma. Blood 111: 1309-1317.

- Wu X, Shao Y, Tao Y, Ai G, Wei R, et al. (2011) Proteasome inhibitor lactacystin augments natural killer cell cytotoxicity of myeloma via downregulation of HLA class I. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 415: 187-192.

- Laffont S, Seillet C, Ortaldo J, Coudert JD, Guéry JC (2008) Natural killer cells recruited into lymph nodes inhibit alloreactive T-cell activation through perforin-mediated killing of donor allogeneic dendritic cells. Blood 112: 661-671.

- Bracci L, Moschella F, Sestili P, La Sorsa V, Valentini M, et al. (2007) Cyclophosphamide enhances the antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred immune cells through the induction of cytokine expression, B-cell and T-cell homeostatic proliferation, and specific tumor infiltration. Clin Cancer Res 13: 644-653.

- Sharabi A, Ghera NH (2010) Breaking tolerance in a mouse model of multiple myeloma by chemoimmunotherapy. Adv Cancer Res 107: 1-37.

- Sharabi A, Haran-Ghera N (2011) Immune recovery after cyclophosphamide treatment in multiple myeloma: implication for maintenance immunotherapy. Bone Marrow Res 2011: 269519.

Citation: Sarkar S, Noort W, Van Elssen CHMJ, Groen R, van Bloois L, et al. (2015) Alloreactive Natural Killer Cells Have Anti?Tumor Capacity Against Disseminated Human Multiple Myeloma in Rag2-/-γC-/-Mice When Combined With Low Dose Cyclophosphamide and Total Body Irradiation. J Clin Immunol Immunother 2: 008.

Copyright: © 2015 Subhashis Sarkar, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.