Analysis of ROBO2 Gene and response of Three Genotypes of Nigerian Indigenous Chicken to Experimental Newcastle Disease Virus Infection

*Corresponding Author(s):

Yeigba B JaphetDepartment Of Animal Science, Faculty Of Agriculture, Niger Delta University Wilberforce Island Yenagoa Bayelsa State, Nigeria

Tel:+234 08138571388,

Email:japhetyeigba@gmail.com

Abstract

ND has been identified as a lethal viral infection associated with high case fetality in poultry. This study was conducted to do a molecular analysis of Roundabout guidance axion (ROBO2) gene and determine the responses of three genotypes of Nigerian indigenous chicken to experimental NDV infection. A total of 180 day-old Nigerian indigenous chicks consisting of 60 Naked neck (NN), 60 Frizzle feather (FF) and 60 Normal feather (NF) (45 experimental and 15 control per genotype) were used for the study. These chicks were immunologically naive to ND. Birds were fed on starter ration (20% CP and 2800 Kcal ME/kg) from day-old to 8th week of age, growers ration (16% CP and 2750 Kcal ME/kg) from 9th to 16th week. Exon 3 of ROBO2 gene of the chickens was amplified and sequenced. The polymorphism in the gene was identified using MEGA 5 and codon code aligner software. Fifteen (15) vials of lyophilised Newcastle live virus Kudu 113 strain were obtained from National Veterinary Research Institute, Vom Plateau State, and each vial was diluted with 2 ml of sterile phosphate buffer saline (pH 7.2). Each experimental genotype chicken was inoculated by intra-crop injection with 0.2 ml of the virus at the 5th week of age. The control group was inoculated 0.2 ml of normal saline. Post infection (PI) observable clinical signs were assessed and live weight changes determined. Blood samples were collected via jugular vein-puncture into Ethylene Diamine Tetra Acetic Acid bottles to determine haematological parameters and plain bottles for determination of Erythrocytes Sedimentation Rate and antibody titre to ND infection on day 7, 14, 21, 28, 35 and 42 PI. Haematological parameters significantly decreased and were most severe in FF compared to NN and NF genotypes. The antibody titre response was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in NN than NF and FF. One SNP (98C>A) was identified in exons 3 of the ROBO2 gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens. Association analyses revealed that the SNP had no significant (p>0.05) effect on the haematological parameters and antibody titre to ND. The study concluded that live-weight changes in naked neck subsequently increased by day 35 and 42 post infection and that of the normal feather had same sequential result. Vaccination against ND is therefore recommended to cub the losses to this disease in the Nigerian indigenous chickens.

Keywords

Breeders; Geneticists; Indigenous Chickens; Farmers; Genotypes; Immune response; Lecturers; Newcastle Virus; ROBO2 Gene; Students

Introduction

In an outbred individual genetically determined variation in the resistance of diseases or susceptibility between individuals is common. Some breeds are inherently resistant or less affected by foreign materials that can be severe to other individuals of the same species. Variations in disease tolerance within strains of birds have long been described [1]. Genetic resistance to diseases is a great resource for the treatment and prevention of diseases and for improvement of productivity in poultry [2,3].The merits of genetic resistance have been said by the emergence of virulent and drug-resistant pathogens, guidelines in the use of antimicrobials and the visibility of certain infections associated with selection for production traits. In the decades, the objective of genetic resistance in disease control in birds was limited reason been that the massive application of chemotherapeutics [4].

Genetically determined diversity of the response of the immune system is the major cause for variations in the resistance to infections of infectious origin [5]. A disease happens to occur if the immune system refuses to respond to protect the body from the injuries inflicted by the invading pathogen, due to insufficient, misdirected immune responses. The immune response against infectious pathogens is an elaborate process and varies among individuals [5].

The first attack of Newcastle disease virus (NDV) occurred in birds in 1926, in Java, Indonesia Kraneveld, Newcastle-upon-Tyne England [6]. Newcastle disease virus (NDV) spread to pose a severe threat to the improvement of poultry industry in Nigeria, and some other parts of Africa and Asia. The disease has ecological as well as economical effect on growing birds, extensively raised birds, as well as local birds. Since the first detection and isolation of NDV in Nigeria in 1951 [7], an average of 200 – 250 outbreaks of the disease were reported in Nigeria yearly [8]. Many of these frequently occurrences in vaccinated herd and they are mostly attributed to the existence of antigenic variations between the vaccine virus and wild virus strains [4,9,10].

There are reports of disease outbreaks in Central Europe similar to what we now recognize as vND that predate 1962, Hill et al., [7] indicated that the disease may have been present in Korea as early as 1924 and considered the death of all the chickens in the western Isles of Scotland in 1896 to be attributable to vND [11].

The name “Newcastle disease” was coined by Doyle as a temporary measure because he wanted to take precautions and avoid a particular name that might be confused with other viruses. No name better than that has been observed in the past 75 years, although for the virus the synonym avian paramyxovirus type 1 (APMV-1) has gained some popularity [9].

Although the various strains of the Newcastle Disease Virus so far seen or identified in the whole world are antigenically similar, minor antigenic variations still appear among strains. The antigenic variations observed within strains are closely related to those found among mutants within the same serotype [10]. These variations are presented by the two surface glycoprotein antigens on the Newcastle Diseae Virus-Haemagglutinin (H) and Neuraminidase (N) [12].

With the antibody titre, infected hens dispose the virus via diarrhea; the virus is later transmitted transovarially into the eggs and the infected chickens subsequently hatched [13]. The transmission of the Newcastle Disease Virus lentogenic strains were shown by Pospíšil et al., [14] who detected the virus in the embryos of the eggs and in the intestinal part of the unvaccinated birds up to the 25thday of hatching. Knowing fully well that the parental herd were vaccinated and the particular maternal antibodies were present in the birds [15].

Local chickens constitute about 60 percent of the 120 million poultry birds found in Nigeria and more than 80 to 85 percent of these poultry herds are found in the rural villages [16]. Fulani (savannah), Yoruba (forest), Nsukka, Owerri and Awgu ecotypes are some of the local ecotypes of chickens around Nigeria [17]. Differences in trait of individual ecotype have been reported by Oluyemi et al., [18], however, there are few of information on the resistance of these ecotypes to virus [19,20]. The inequality of animal protein as well as production is increased in human population within Nigeria and made the consumption of animal protein higher, therefore, the availability of animal protein is always needed. In addition to high protein demand, diseases that are viral and bacterial in nature such as Newcastle Disease is also tend to decrease the population of poultry production [20].

Haemagglutination inhibition test is recentlya widely used and conventional serological methodology for analysing anti-NDV antibody response in poultry sera [21].

The (ROBO2) gene has 32 exons and 25 introns, its location is in chromosome 1 with 1,285,637,921bp and the exon 3 has 139bp.

Materials And Methods

Experimental site

The experiment was carried out at the College of Veterinary Medicine, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta located within Odeda Local Government Area of Ogun State, a place where poultry has never been previously raised or reared. The area lies in the South-Western region of Nigeria between Oyo and Lagos States in Nigeria and it has a prevailing tropical climate with a mean annual rainfall of about 1037mm. The mean temperature ranges from 28oC in December to 36oC in February with a yearly average of 34oC. Relative humidity ranges from 60% in January to 94% in August with a yearly average of about 82% [22].

Pre-experimental screening of eggs incubated for experimental birds

To ensure that the birds hatched do not have maternal immunity to Newcastle disease, before eggs were sent to the hatchery, three eggs were randomly selected from each of the genotypes (Normal, Frizzle and Naked Neck) to test if they were immunologically naive to Newcastle disease.

Methods used for screening of eggs

Fresh egg was cracked and the yolk was dropped intact in a petrish dish, a 5ml syringe was inserted into the centre of the yolk and 1ml was deposited in the PBS solution. 1ml of Phosphate buffer solution (PBS) was placed into bottles and 1ml of yolk was added and the mix-ratio was added together, thereafter the mixture was centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10minutes, the supernant was then removed and was used for Haemagglutination inhibition test according to the standard method [23].

Experimental birds and management

The eggs were generated through artificial insemination of the parent stock in the farm, and the eggs collected were screened with Haemagglutination inhibition to Newcastle disease and after confirmation, the eggs were taken to the hatchery section of the Animal Breeding and Genetics Department (FUNAAB) for setting. Eggs taken to the hatchery were labelled with the genotype of their dam for easy identification. The eggs were set into a disinfected tray that consists of holes that will house each egg. The tray were disinfected 2 days prior to the day of setting eggs with formaldehyde or formalin chemical so as to remove any existing contamination from the tray. The disinfected tray was allowed to dry by placing it in the sunlight, after which eggs were arranged into it for setting. The arranged eggs were candled on the 18th day of setting/incubation and hatched chicks were collected on the 21st day of setting after which the chicks were all raised according to genotypes under the same management practice.

Rearing day-old chicks of three genotypes of Nigerian indigenous chickens

A day-old, all chicks were brooded together in the same cage and after 4 weeks of age they were separated according to genotype for both the experimental and the control for acclimatisation for another week (5 week) prior to the commencement of the experiment. Experimental birds to be infected and those in the control were reared in cages with wire-mesh basement in order for them not to have access to their faecal droppings. They were reared in an intensive system with water and feed supply ad libitum. The control were similarly housed in the same vicinity but about 70 to 80 meters away from where the infected experimental birds were raised. Management practice was the same.

Feeding

Birds were fed a starter ration (20% CP and 2800 Kcal ME/kg) from day-old to 8th week of age, growers ration (16% CP and 2750 Kcal ME/kg) from 9th to 16th week of age, feeding and water supply were ad libitum for all birds both the experimental and control.

Experimental birds grouping

A total of 180 day-old Nigerian indigenous chicks that were immunologically naive to Newcastle disease were randomly allocated into three groups according to genotypes of 60 chicks each, 45 for experiment and 15 were raised as control respectively. The experimental birds were raised under the same environment and management practice.

Newcastle disease virus inoculation and challenge of chickens

Fifteen (15) vials of the lyophilised Newcastle live virus Kudu 113 strain were obtained from National Veterinary Research Institute, Vom, Plateau State, and each vial was diluted with 2ml of sterile phosphate buffer saline (pH 7.2). Each chicken was inoculated by crop-intra-crop injection with 0.2ml of the virus at the 5th week of age. Chickens in the control group were inoculated 0.2ml of normal saline.

Clinical and performance examination

Initial body weight was taken before the commencement of the experiment and this was done in a weekly basis. All the experimental/control birds were observed twice daily for clinical manifestations and mortality up to 4weeks post infection. The presentation of clinical signs was the modification of the system used by Ogie et al., [20], with (-) indicating no clinical signs; (+) indicates drowsiness and occasional closure of the eyes while (++) indicates closure of the eyes and reluctance to move. Dead chickens were examined for gross lesions (Post mortem), samples of the spleen, liver, brain, lung, caecum, intestine and kidney were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, processed, embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned. They were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H and E) and were examined under light microscope at the magnification of x200. The remaining chickens were sacrificed at the end of the experiment.

Blood collection

Blood sample were collected through the jugular venepuncture, using 2ml syringes and sterile hypodermic needles. About 0.5-1ml of blood was collected from individual bird weekly from week 5 to 10 post infection and all the samples were labelled accordingly both from the experimental and the control chickens.

Determination of Haematological parameters

Blood samples for haematology were collected into bottles containing Ethylene Diamine Tetra-Acetic acid (EDTA). Parameters that were evaluated include: Packed Cell Volume (PCV), red blood cell count (RBC), white blood cell count (WBC), haemoglobin concentration (Hb) and erythrocyte indices such as mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC), mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) were calculated using the PCV, RBC and Hb values.

Blood sample for serum collection

Part of the blood samples were collected in plain bottles and were allowed to stand for 30 minutes for sera formation, after which the sera were collected in an ependorf tubes and stored in a freezer until ready for use. These sera samples were used for Haemagglutination inhibition (HI) tests to evaluate the antibody titre concentration against Newcastle disease virus [23], using micro-titre method. LaSota vaccine was used as the source of antigen. The serum samples were separated by centrifugation at 1,000g for 10min and frozen in plastic vials until the HI titre was determined.

Mortality (%)

Percentage mortality: this was calculated as the ratio of number of dead birds to the total number of birds per replicate, expressed as percentage.

Mortality (%) = number of dead birds per replicate / Total number of birds stocked per replicate

Packed Cell Volume (%)

The percentage of packed cell in the blood was determined using the haematocrit centrifuge method as described by [24]. A capillary tube was dipped into blood sample to fill it to about three-quarter length. Excess blood on the side of the capillary tube was wiped off in order to keep accurate reading. One end of the tube was sealed over a Bunsen burner. The capillary tube was put into a micro-haematocrit reading and the levels of packed cells were regarded as the packed cell volume.

Red Blood Cell count (×10 12/1L)

Blood collected into EDTA bottle was diluted with 0.9% NaCl, mixed together. The diluted blood was mounted on a haemocytometer and the number of erythrocytes in a circum scribed volume (0.02 mm) was counted microscopically. Calculated erythrocytes was expressed in million per cubic milliliter [25].

Haemoglobin concentration (9m/dl)

The Hb concentration of each blood sample was determined by cyanomethaoglobin method as described by Jain [26]. For each blood sample, 20µl of blood were mixed with 4ml of modified (Drabkin’s solution was prepared by mixing 200mg potassium ferricyanide, 50mg potassium cyanide and 140mg potassium dihydrogen phosphate; volume was made up to 1 litre with distilled water and pH adjusted to 7.0). The mixture of blood sample of experimental birds and Drabkin’s solution was allowed to stand for 3 minutes before the haemoglobin concentration were read using a spectrophotometer at wavelength of 540nm.

White Blood Cell count and its differentials (×10 9/6)

The estimate of the total number of white blood cells was carried out on the blood sample collected from experimental birds using Neubaurer haemocytometer counting chamber [26]. From the sample 0.2 ml of blood were collected using pipette and mixed with 4ml of WBC diluting fluid (WBC fluid made up of 3% aqueous solution of acetic acid and 1% gentian violet). This was then taken into the haemocytometer and the white blood cells were counted and expressed as 109 WBC per litre of blood. The differential counts were also determined by making blood films, air drying it and then staining with wright stain and the WBC counts was performed using standard avian guidelines of Ritchie et al., [27]. A Heterophil/lymphocyte ratio was calculated.

Mean Corpuscular Haemoglobin Concentration

The mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration is a measure of the concentration of haemoglobin in a given volume of packed red blood cells. It was calculated by the formula: MCHC= Hb/PCV x 100 (g/dl).

Mean corpuscular Haemoglobin

Mean corpuscular Haemoglobin is the average mass of haemoglobin per red blood cell in a sample of blood. It was reported as part of a standard complete blood count. It was calculated by dividing the total mass of haemoglobin by the number of red blood cells in a volume of blood. It was calculated by the formula: MCH=Hb/RBCx10 (pg).

Mean Corpuscular Volume

The mean corpuscular volume is a measure of the average red blood cell volume reported as part of a standard complete blood count. It was calculated using the formula: MCV= PCV/RBCx10 (fl).

Differential leucocyte count

The relative number of each type of white blood cell was established by the differential white cell count [28].

Staining Procedure

- Place a drop of well mixed anti-coagulated blood on a clean grease free slide

- With good and smooth edge spreader, make a thin film to have a good tail end

- Air dry it and place on staining rack

- Flood it with Leishman stain and leave to fix for 2 minutes

- Dilute with buffered distilled water of PH 6.8 and leave for 10 minutes for staining.

- Allow to dry and examine under the microscope using X 100 objective.

Procedure of Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate

- Mix the blood sample thoroughly

- Draw it up into Westergren tube to the 200mm mark

- Place the tube exactly vertical and leave undisturbed for 60mintes

- Read the height of the clear plasma above the upper limit of the column of sedimenting cells to nearest mm.

- Record your result in mm/hrs

Stages of sedimentation

- Preliminary stage: Few minutes during which rouleaux form, this is controlled by the concentration of fibrinogen and globulin present.

- Sinking stage: Period in which the sinking of the rouleaux takes place at approximately a constant speed.

- Final stage: A phase during which the rate of sedimentation slows as the rouleaux pack at the bottom of the tube.

Serological test

Preparation of Red Blood Cells suspension: Three milliliter (3ml) of blood sample were collected from a mature chicken (not part of the experiment with the packed cell volume determined) into EDTA bottle; this was transferred into a test tube, and Centrifuge for 2000-3000 rev/min for 5 min, the supernatant was decanted and freshly prepared phosphate buffer saline (PBS) was added. The test tube was then gently rocked to red blood cells. Centrifugation, decantation and addition of PBS were repeated three times or until the supernatant was clear.

Preparation of 0.5% Red Blood cell suspension: One milliliter (1ml) of prepared red blood cell suspension was collected into a test tube then the formula; C1V1=C2V2 was used to calculate the volume of freshly prepared PBS to be added to make 0.5% RBC suspension; where C1=PCV of the blood collected from the mature chicken, V1=1 ml (initial volume of RBC suspension collected), C2= 0.5 (% of RBC to be gotten), V2=? (volume of PBS to be added to make 0.5% RBC suspension).

Haemagglutination test: Each micro-titre well on the first row (A1 to A12) of a micro-titre plate were filled with 50µl PBS Fifty micro-titres (50µl) of diluted LaSota vaccine were added to the first well (A1) and double diluted serially to the eleventh well (A11) on the row. Fifty micro-litres (50µl) of 0.5% RBC suspension were added to each of the well starting from the first (A1) to the last well (A12). They were then allowed to incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature. Then the wells were read while well A12 served as the negative control. Positive result: RBC evenly distributed at the bottom of the plate, negative result: RBC clump together to form a button like shape. Antibody titre value is the inverse of serum dilution giving 100% haemagglutination [23].

Haemagglutination inhibition test: The 4 HA (standard unit for HI test) of the diluted LaSota vaccine were calculated using the formulae: C1V1= C2V2. C1=HA unit of the diluted LaSota vaccine, V1t= 1ml (initial volume of diluted Lasota vaccine collected), C2=4 (HA standard unit), V2=? (volume of PBS to be added to make 4 HA unit of diluted LaSota vaccine).

Fifty microliters (50µl) of PBS were placed into the micro-titre wells across the rows and along the columns depending on the number of sample to be analysed (well 1-12). Each row was used for one serum sample (i.e. serum sample 1 for rows A1-A12). 50µl of each serum sample was added to the diluted LaSota vaccine (4 HA unit) and were added into each well from well 1 to well 12. Fifty microliters (50µl) of 0.5% RBC suspension was added to each well and allowed to incubate for 30mins. Results were read and values were reciprocal of serum dilution with 100% haemagglutination [23]. Negative result: if RBC were evenly distributed and positive result if RBC clump together to form a button like shape at the bottom of plate.

Polymorphism Identification

Primer was used to amplify a fragment of genomic DNA to identify polymorphic sites in exon 3 and the5′/3′ UTR of the ROBO2 gene from the Nigerian indigenous chickens. PCR amplification was performed in a 25-μL reaction volume on a Gene Amp PCR system 9600 (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA). Mixture was composed of 100 ng of chicken genomic DNA as a template, primersat 1μleach. PCR reaction mix, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Dongsheng, Guangzhou, China). The PCR amplifications were performed with the following cycling parameters: initial denaturation at94°C for 4 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, annealing at the optimal temperature for 45s, and 72°C for 1 min.

A final extension was performed at 72°C for 10 min. All amplified products were separated on agarose gels and purified using a Gel Extraction Kit (Sangon). The purified PCR products were cloned into the pMD19-T vector (TaKaRa) and sequenced in both directions. Potential polymorphic sites were analyzed by sequence comparison using DNA star software.

Primer used in this study (Table 1)

|

Primer Name |

Primer sequence (5′–3′) |

|

Binding |

ProductAnnealing |

|

Region |

size (bp) temperature |

|

|

|

|

5NGSP-R2 |

TCCAGTAGATGGTAGGCTCAGGGTGTCC |

- |

Exon 3 |

60 |

|

F |

AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT |

|

|

|

Table 1: Source [29].

Multiple sequence alignment

The sequence obtained for exon 3 was aligned with a reference exon 3 to cut out the exon for the analysis. The alignment was carried out on all the nucleotide sequences using Clustal W software [30] embedded in MEGA 6 software.

Identification and analysis of single nucleotide polymorphism

The SNP present in exon 3 of ROBO2 gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens were identified by aligning the exon with the reference exon downloaded from Esembl database using Clustal W [30].

Evolutionary analysis

The frequency of nucleotides present in exon 3 of ROBO2 gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens was determined using MEGA 6 software.

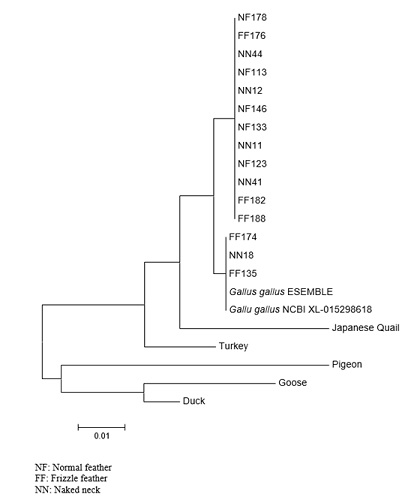

MEGA 6 software was used to determine the phylogenetic relationship among exon 3 of ROBO2 gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens, other chicken genotypes was used as reference sequences (Gallus gallus sequence extracted from ESEMBL and NCBI with accession number XL-015298618), Japanese quail, Turkey, Pigeon, Goose and Duck.

Statistical analysis

Data collected were subjected to one-way analysis of variance using appropriate least squares method with genetic group as the main source of variation. Significant means were separated using Duncan’s multiple range tests of the Statistical Analysis Software [31].

Model

Yij= µ + Ti + eij

Where

Yij = observation of population variable

µ = sample mean

Ti = effect of ith genotype group

Eij = random residual error with zero mean and variance component

Association analysis

Preliminary analysis of SNP revealed that the identified SNP are synonymous and the others non-synonymous which cannot be used for association study because it has no effect on the amino acid. Therefore, the association study was done based on SNP identification using Proc Mixed of SAS [32] with the model listed below:

Y =Xβ + γ + ε

Y is the dependent variable such as the clinical signs observed, morbidity and mortality rate in response to Newcastle disease virus infection.

X=is the candidate SNP

β =effect of genotype group

γ =effect of genotype in response to Newcastle disease virus

ε =random residual error

SNPs shared by the three genotypes were only used for the association study analysis.

Results

Mean packed cell volume (PCV %) of three Nigerian indigenous chickens experimentally infected with Newcastle virus and the control

Table 2: Shows the PCV level following experimental Newcastle virus infection in three genotypes of Nigerian indigenous chickens. Day 7 post infection showed no significant (p>0.05) differences in PCV of normal feather (28.31±2.43), frizzle feather (27.84±3.00) and naked neck (29.52±3.03). However, by day 14 post infection there was a decline in PCV of the normal feather (25.96±3.61) but no significant (P>0.05) difference while frizzle feather (22.62±3.75) and naked neck (26.10±2.29) decreased with significant (p < 0.05) differences. By day 21 post infection linear decline in PCV in normal feather (22.08±3.04) and naked neck (25.20±2.98) while in frizzle feather there was 100% mortality by day 18 post infection. In day 28, 35 and 42 in normal feather and naked neck there was slight increase in PCV with no significant (p>0.05) difference.

|

Within genotype |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Genotypes |

7 |

14 |

21 |

28 |

35 |

42 |

|

Normal feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Infected = 35 |

28.31±2.43a |

25.96±3.61a |

22.08±3.04b |

29.00±1.00a |

28.00±1.41a |

0 |

|

Control = 15 |

26.67±2.60a |

28.42±3.26a |

28.50±1.83a |

28.42±2.77a |

28.50±2.11a |

27.75±2.17 |

|

Frizzle feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Infected = 32 |

27.84±3.00a |

22.62±3.75b |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Control = 15 |

28.07±2.81a |

28.36±2.62a |

27.50±1.91 |

28.46±2.79 |

29.14±2.10 |

28.07±2.84 |

|

Naked neck |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Infected = 42 |

29.52±3.03a |

26.10±2.29b |

25.20±2.98b |

28.26±3.48a |

27.33±1.80a |

27.78±1.48a |

|

Control = 15 |

30.27±2.71a |

31.00±4.12a |

31.40±3.99a |

31.80±4.05a |

30.60±2.79a |

30.15±3.32a |

|

|

|

|

Between genotype |

|

|

|

|

Normal feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Infected = 35 |

28.31±2.43a |

25.96±3.61a |

22.08±3.04b |

29.00±1.00a |

28.00±1.41a |

- |

|

Frizzle feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Infected = 32 |

27.84±3.00a |

22.62±3.75b |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Naked neck |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Infected = 42 |

29.52±3.03a |

26.10±2.29b |

25.20±2.98b |

28.26±3.48a |

27.33±1.80a |

27.78±1.48a |

Table 2: Mean Packed cell volume (PCV %) of three Nigerian indigenous chickens experimentally infected with Newcastle virus and the control.

Subscript a,b of same column with different superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05)

Mean Haemoglobin (Hb g/dl) concentration of three Nigerian indigenous chickens experimentally infected with Newcastle virus and the control

Table 3: Shows the haemoglobin (Hb) level following experimental Newcastle virus infection in three genotypes of Nigerian indigenous chickens and control. Day 7 post infection showed no significant (p>0.05) differences in Hb of normal feather (7.57±1.28), frizzle feather (8.22±1.32) and naked neck (9.18±1.06). However, by day 14 and 21 post infection, normal feather (6.67±1.28) decreased and increased (7.23±1.18) at day 21, frizzle feather (6.09±1.50) declined subsequently at day 14 and had 100%mortality at day 18 and in naked neck there was a decrease (7.63±1.11) and (7.65±1.31) by day 28. 35 and 42 post infection there was an increase on haemoglobin but had no significant (p>0.05) difference while naked neck (8.67±1.61) at day 28 had an increasing haemoglobin and subsequently decreased at day 35 and 42.

|

Within genotype |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Genotypes |

7 |

14 |

21 |

28 |

35 |

42 |

|||

|

Normal feather |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Infected = 35 |

7.57±1.28a |

6.67±1.28a |

7.23±1.18a |

7.63±2.05a |

8.90±0.14a |

- |

|||

|

Control = 15 |

7.45±0.70a |

7.05±1.15a |

8.13±1.47a |

6.98±0.85a |

8.00±1.51a |

8.12±0.35a |

|||

|

Frizzle feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 32 |

8.22±1.32a |

6.09±1.50b |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|||

|

Control = 15 |

7.69±0.94a |

7.88±1.17a |

7.35±1.48 |

7.27±1.09 |

7.58±0.72 |

7.35±1.21 |

|||

|

Naked neck |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 42 |

9.18±1.06a |

7.63±1.11b |

7.65±1.31b |

8.67±1.61a |

8.66±0.91b |

8.20±044b |

|||

|

Control = 15 |

9.47±0.76a |

9.12±0.74a |

9.25±0.82a |

9.17±0.55a |

9.92±0.89a |

9.04±0.92a |

|||

|

|

|

|

Between genotype |

|

|

|

|||

|

Normal feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 35 |

7.57±1.28a |

6.67±1.28a |

7.23±1.18a |

7.63±2.05a |

8.90±0.14a |

- |

|||

|

Frizzle feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 32 |

8.22±1.32a |

6.09±1.50b |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|||

|

Naked neck |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 42 |

9.18±1.06a |

7.63±1.11b |

7.65±1.31b |

8.67±1.61a |

8.66±0.91b |

8.20±044b |

|||

Table 3: Mean Haemoglobin (Hb g/dl)concentration of three Nigerian indigenous chickens experimentally infected with Newcastle virus and thecontrol.

Mean Red blood cell (RBC×1012/1L) of three Nigerian indigenous chickens experimentally infected with Newcastle virus and the control

Table 4: Revealed the RBC level following experimental Newcastle virus infection in three genotypes of Nigerian indigenous chickens and control. Day 7 and 14 post infection showed significant (p<0.05) differences in normal feather (2.62±0.31) and (2.43±0.23), frizzle feather (2.75±0.18) and (2.38±0.23) while naked neck (2.90±0.18) and (2.78±0.20) had no significant (p>0.05) differences. However, by day 21 post infection, there was linear decrease in RBC for normal feather (2.45±0.24) and naked neck (2.82±0.17) while frizzle feather had 100% mortality at day 18. By day 28, 35 and 42 there was an increase in RBC in normal feather and naked neck with no significant differences.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Within genotype |

|

|||

|

Genotypes |

7 |

14 |

21 |

28 |

35 |

42 |

|||

|

Normal feather |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Infected = 35 |

2.62±0.31b |

2.43±0.23b |

2.45±0.24b |

2.63±0.30a |

2.79±0.12a |

- |

|||

|

Control = 15 |

2.84±0.29a |

2.70±0.18a |

2.69±0.23a |

2.71±0.21a |

2.62±0.23a |

2.64±0.15 |

|||

|

Frizzle feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 32 |

2.75±0.18b |

2.38±0.23b |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|||

|

Control = 15 |

2.95±0.19a |

2.82±0.24a |

2.62±0.35 |

2.67±0.35 |

2.68±0.28 |

2.66±0.21 |

|||

|

Naked neck |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 42 |

2.90±0.18a |

2.78±0.20a |

2.82±0.17b |

2.84±0.23a |

2.96±0.24a |

2.90±0.18a |

|||

|

Control = 15 |

2.90±0.23a |

2.89±0.18a |

2.61±0.31a |

2.54±0.27b |

2.70±0.26b |

2.87±0.24a |

|||

|

|

|

|

Between genotype |

|

|

|

|||

|

Normal feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 35 |

2.62±0.31b |

2.43±0.23b |

2.45±0.24b |

2.63±0.30a |

2.79±0.12a |

- |

|||

|

Frizzle feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 32 |

2.75±0.18b |

2.38±0.23b |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|||

|

Naked neck |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 42 |

2.90±0.18a |

2.78±0.20a |

2.82±0.17b |

2.84±0.23a |

2.96±0.24a |

2.90±0.18a |

|||

Table 4: Mean Red blood cell (RBC×1012/1L) of three Nigerian indigenous chickens experimentally infected with Newcastle virus and the control.

Subscript a,b of same column with different superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05)

Table 5: Shows the (WBC) level following experimental Newcastle virus infection in three genotypes of Nigerian indigenous chickens and control. Day 7 post infection shows no significant (p>0.05) differences normal feather (19.55±3.26) and naked neck (20.66±2.72) while frizzle feather was significantly (p < 0.05) different. By day 14 normal feather (20.36±3.32) was increased but had no significant (p>0.05) difference, frizzle feather (12.32±1.46) and naked neck (22.92±3.03) declined subsequently. However, by day 21, 28, 35 and 42 there was no significant (p>0.05) differences having significantly increased values except day 21 of the naked neck (21.84±3.03) which was significantly (p < 0.05) different.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Within genotype |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Genotypes |

7 |

14 |

21 |

28 |

35 |

42 |

|||||||||

|

Normal feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Infected = 35 |

19.55±3.26a |

20.36±3.32a |

18.86±5.34a |

26.03±2.00a |

25.70±1.13a |

- |

|||||||||

|

Control = 15 |

20.49±2.53a |

20.13±3.36a |

19.20±6.19a |

18.38±4.69b |

21.18±4.20b |

19.19±5.30 |

|||||||||

|

Frizzle feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Infected = 32 |

17.40±3.38b |

12.32±1.46b |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|||||||||

|

Control = 15 |

19.84±2.44a |

18.40±5.72a |

17.10±5.21 |

18.15±3.02 |

17.87±2.61 |

17.69±4.30 |

|||||||||

|

Naked neck |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Infected = 42 |

20.66±2.72a |

22.92±3.03b |

21.84±3.03b |

21.93±3.04a |

21.46±2.23a |

23.31±2.60a |

|||||||||

|

Control = 15 |

19.84±2.10a |

18.56±3.05b |

19.75±1.63a |

21.14±2.08a |

19.96±1.70a |

20.18±5.44a |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

Between genotype |

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Normal feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Infected = 35 |

19.55±3.26a |

20.36±3.32a |

18.86±5.34a |

26.03±2.00a |

25.70±1.13a |

- |

|||||||||

|

Frizzle feather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Infected = 32 |

17.40±3.38b |

12.32±1.46b |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|||||||||

|

Naked neck |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Infected = 42 |

20.66±2.72a |

22.92±3.03b |

21.84±3.03b |

21.93±3.04a |

21.46±2.23a |

23.31±2.60a |

|||||||||

Table 5: Mean Whites blood cell (WBC×109/6) of three Nigerian indigenous chickens experimentally infected with Newcastle virus and the control.

Subscript a,b of same column with different superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05)

Mean Erythrocytes Sedimentation Rate (ESR mm/hr) of three Nigerian indigenous chickens experimentally infected with Newcastle virus and the control

Table 6: Shows the Erythrocytes Sedimentation Rate (ESR) level following experimental Newcastle virus infection in three genotypes of Nigerian indigenous chickens and control. Day 7 post infection showed no significant (p>0.05) differences across the all genotypes of the infected group except that of the frizzle feather that was recorded 100% mortality as at day 28 with zero mean value (0.00±0.19) and(0.00±0.26) respectively. However, there was no significant (p>0.05) differences recorded in the control.

|

Within genotype |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Genotypes |

Before infection |

14days |

28 |

42 |

||

|

Normal feather |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Infected = 35 |

3.014±0.17a |

4.72±0.23a |

4.13±0.48a |

5.65±0.52a |

||

|

Control = 15 |

3.225±0.30a |

2.98±0.30b |

2.54±0.24b |

2.46±0.22b |

||

|

Frizzle feather |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Infected = 32 |

3.13±0.13a |

4.98±0.22a |

- |

- |

||

|

Control = 15 |

3.47±0.23a |

2.84±0.33b |

2.47±0.12a |

2.62±0.17a |

||

|

Naked neck |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Infected = 42 |

3.29±0.12a3.31±0.23a |

5.75±0.23a |

6.01±0.27a |

6.01±0.50a |

||

|

Control = 15 |

3.18±0.39b |

3.23±0.23b |

2.88±0.41b |

|||

|

|

|

Between genotype |

|

|

||

|

Normal feather |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Infected = 35 |

3.014±0.17a |

4.72±0.23a |

4.13±0.48a |

5.65±0.52a |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Frizzle feather |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Infected = 32 |

3.13±0.13a |

4.98±0.22a |

- |

- |

||

|

Naked neck |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Infected = 42 |

3.29±0.12a |

5.75±0.23a |

6.01±0.27a |

6.01±0.50a |

||

Table 6: Mean Erythrocytes Sedimentation Rate (ESRmm/hr) of three Nigerian indigenous chickens experimentally infected with Newcastle virus and the control.

Subscript a,b of same column with different superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05)

Mean Antibody titre of three Nigerian indigenous chickens experimentally infected with Newcastle virus and the control

Table 7: Shows the antibody titre level following the experimental Newcastle virus infection in three genotypes of Nigerian indigenous chickens and their control. Day 7 post infection showed no significant (p>0.05) differences across the genotypes of the infected group except that of the frizzle feather that recorded 100% mortality as at day 28 with zero mean value (0.00±0.42) and(0.00±0.44) respectively. However, there was no significant (p>0.05) differences recorded in the control except the control of the naked neck genotype.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Within genotype |

|

|

Genotypes Day-old |

Before infection |

14days |

28 |

42 |

|||

|

Normal feather |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 35- |

1.87±0.17a |

32.84±5.59a |

42.67±4.39a |

48.00±4.89a |

|||

|

Control = 15 |

1.63±0.25a |

2.08±8.07b |

2.00±2.29b |

1.82±2.08b |

|||

|

Frizzle feather |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 32- |

1.89±0.18a |

19.82±4.63a |

- |

- |

|||

|

Control = 15 |

2.30±0.35a |

1.80±6.87b |

1.60±0.27a |

1.63±0.31a |

|||

|

Naked neck |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 42- |

1.79±0.12a |

74.29±7.32a |

94.4±19.2a |

88.9±17.2a |

|||

|

Control = 15 |

1.25±0.22b |

2.5±12.5b |

1.6±17.6b |

1.7±17.2b |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Between genotype |

|

|

|||

|

Normal feather |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 35- |

1.87±0.17a |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

32.84±5.59a |

42.67±4.39a |

48.00±4.89a |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Frizzle feather |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 32- |

1.89±0.18a |

19.82±4.63a |

- |

- |

|||

|

Naked neck |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Infected = 42- |

1.79±0.12a |

74.29±7.32a |

94.4±19.2a |

88.9±17.2a |

|||

Table 7: Mean Antibody Titre of three Nigerian indigenous chickens experimentally infected with Newcastle virus and the control.

Subscript a,b of same column with different superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05)

Association study of ROBO2 Gene haematological traits and body weight of the infected Nigerian indigenous chickens

Table 8: Shows the association of PCV, WBC, RBC, ESR, Hb and BW of the three genotypes of Nigerian indigenous chickens after the alignment of the region of sequence used in this research. Following the alignment result, only one SNP was found changes from C to A of which the reference sequence of the same region carries the C nucleotide. The parameters after the association study had no significant differences (p<0.05) as well as the p-value except the p-value of ESR (0.6015) and Hb (0.7449) that was significant (p<0.01). However, the body weight had the highest values based on the association of the SNP alleles, followed by the PCV, HA, WBC, ESR, Hb and RBC respectively.

|

SNP allele |

PCV |

WBC |

RBC |

ESR |

HB |

BW |

HA |

|

|

A |

|

28.00±0.98 |

21.18±1.90 |

2.50±0.18 |

5.10±0.48 |

5.94±1.20 |

186±14.01 |

53.13±16.19 |

|

C |

|

25.33±1.95 |

17.97±3.16 |

2.28±0.30 |

5.67±0.96 |

4.57±1.93 |

216.55±22.23 46.13±26.59 |

|

Table 8: Association study of ROBO2 Gene haematological traits and body weight of the infected Nigerian indigenous chickens.

Resultant amino acid variations and predicted effects of SNP identified in exon 3 of ROBO2 gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens

Table 9: Shows the resultant amino acid variations and predicted effects of SNP identified in exon 3 of ROBO 2 gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens is presented in table 9. The SNP identified in exon 3 of ROBO 2 gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens were not synonymous and therefore, its affecting the codon, protein or the amino acid.

|

Region |

SNP |

|

codon change |

|

Amino acid variation |

Type of Mutation |

|

|

|

Exon 3 |

|

|

98C>A |

|

98CCG→CAG |

Proline→Glutamine |

|

non-Synonymous |

Table 9: Resultant amino acid variations and predicted effects of SNP identified in exon 3 of ROBO2 gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens.

The position of the SNP occurred is in bold.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic relationship between exon 3 of ROBO 2 gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens and other chicken genotypes is shown in figure 1. Two clades were formed with exon 3of Naked neck, frizzle feather and normal feather chickens forming sister taxa in one clade while other chicken genotypes formed another five taxa in another clade.

Figure 1: Phylogenetic relationship between exon 3 of ROBO 2 gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens namely Normal feather, Frizzle feather, Naked neck and other Chickens genotypes.

Figure 1: Phylogenetic relationship between exon 3 of ROBO 2 gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens namely Normal feather, Frizzle feather, Naked neck and other Chickens genotypes.

Discussion

Newcastle disease is a global disease of enormous economic importance and regarded as a very significant pathogen [33].The virus is capable of infecting a large number of avian species with varying degrees of clinical manifestation in different age groups, principally due to mortality and the effects on the quality and quantity of meat and eggs produced by affected birds. In the present study, there were no losses of weight or mortality in the unchallenged chickens. Clinically, challenged birds were observed to show vivid depression, reluctance to move, huddling, greenish yellow diarrhoea, resting on the beak, dropping wings, lack of appetite, oedema, mocoid discharge from the mouth, pecking of floor/base, gasping and making of crack sound before death. Post-mortem examination of dead birds revealed petechiation of the serous mucosa, haemorrhage and necrosis of the mucosa surface, congestion of the lungs and mucoid exudates in the respiratory tract as well as opacity and thickening of the air sacs membrane. The beginning of clinical signs on the third and fourth day post infection recorded in this study agreed with the findings of Msoffe et al., [34] and Fayeye et al., [35]. Similarly the onset of mortality recorded in this study concurs with the report of Msoffe et al., [34]. The variable mortality rates obtained among the three genotypes tends to agree with Akinoluwa et al., [36] who obtained 40%, 30% and 70% for Yoruba frizzle, Yoruba naked neck and Yoruba smooth feathered respectively. The relatively higher mortality observed in this study for frizzle feather chickens was higher compared to other genotypes and it does not agree with the earlier report by Akinoluwa et al., [36].

The least mortality observed among the naked neck chickens is in harmony with El-Safty et al., [37] who reported that naked neck have a better ability to secret Acute Phase Protein (APP) by liver cells, which gives protection to the birds against infection or any invasion. The 100% mortality observed among the frizzle feathered chickens in the crop-intra-crop route of inoculation, which is further confirmed by GMT of HI antibodies and failure to develop protective immunity in the 21st day of infection is in agreement with OIE [38] that antibody titre less than Log2 22 may not be protective and this is probably be the reason why the genotype had highest mortality. The high mortality reported in the frizzled feather genotype was also similar to the report by Bratt and Clavell [39] when they challenged chickens with the viscerotropic velogenic strain of Newcastle disease virus.

The incubation periods of virus in the three genotypes fell within the range of 2 to 14 days which was in line with the findings of Bratt and Clavell [39], who reported its incubation period of the challenged local chickens, fell within the range of 2 to 15 days. The early stage of morbidity and death suggest that the challenged virus used was highly virulent.

The onset of morbidity and clinical signs of infected birds in this study was similar to that observed by Oladele et al., [40] in their study on exotic chickens (Shaver Brown) infected with a local Nigerian strain of velogenic Newcastle disease virus. Msoffe et al., [34] observed onset of morbidity for Newcastle disease at day 3, onset of mortality at day 5 after inoculation/infection, and mortality rate between day 5 and 7 of 95 percent in their study on four Tanzanian ecotype chickens and this findings is in agreement with the present research and that of the observations of Alexander [41], who reported the lack of breed or genetically determined resistance to Newcastle Disease. Hassan et al., [42] however observed that the Mandarah local chickens emerged as a resistant breed with only 20% mortality compared with three other Egyptian chicken ecotypes which had 85-100% mortality in agreement with the present study where the Naked neck genotype had the lowest percentage mortality of 20%.

The clinical signs observed in the inoculated chickens were also similar to those produced by the viscerotropic velogenic strain as reported by Morgan-Capner and Bryden [43].

The host immune response to viruses is a complex process. The antibody response to NDV can be considered to be a quantitative trait under polygenic control, but with some QTLs [44]. The results of this study showed the presence of Newcastle disease antibodies in the sera of local chickens, it’s a contagious disease of chicken. This finding confirms earlier reports by Spradbraw [45] and Alexander [46] who reported that, Newcastle disease is the major constraint to the production of local chickens in many developing countries.

Ekue et al., [47] also reported that the disease is the principal limiting factor in rural poultry farming. Furthermore, the result obtained in this study is in agreement with the field observation by Fayeye et al., [35] who stated that the local chickens are as susceptible to Newcastle disease virus as their exotic breeds/counterpart, and reports by Mai et al., [48] in local ducks and local guinea fowls in Nigeria.

Antibody response to Newcastle disease virus after inoculation differs in Nigerian indigenous chickens with naked neck chickens having the highest immune response. Antibody response to the same virus differs among chicken genotypes [49] and selection for an antibody response may improve disease resistance in chickens [50]. According to Oladele et al., [51] the HI titre for unvaccinated local chicken with no history of Newcastle disease ranged between 23 and 27.The high HI values for the control local chicken in the present study suggest that vaccination was effective in raising the residual antibodies in the local chicken. Spanoghe et al., [52] reported that birds challenge with velogenic Newcastle disease virus (NDV), showed high post-vaccinal serum HI-titres were correlated with complete resistance to clinical disease but not to infection. The high value of antibody titre in test sera is due to an attempt by innate immunity in the Newcastle virus challenged birds to resist the invading velogenic virus. Njue et al. (undated)reported that the productivity of village chicken is likely to improve through better feeding regime and vaccination against Newcastle disease.

The highest immune responses observed in the naked neck genotype have also been reported by Fathi et al., (2005) [53], Fathi et al., [54] (2008) and Galal [55]. Rajkumar et al., [56] reported that naked neck allele in homozygous condition increased cell mediated immunity to phytohaemoagglutin-P and antibody titres to sheep red blood cell antigens compared to other genotypes.

This suggests that the local chickens are fully susceptible to the Newcastle disease virus and should be considered as an important factor in the epidemiology of the disease. The significance of this disease to the rural farmers is not only due to high mortality of chickens but that such affected chickens if survived could eventually become carriers and enhance the dissemination of the virus to other healthy susceptible flocks.

Disease resistance in young chicks is very crucial for the survival as well as the production of chickens [57]. The variation in the immune response of young indigenous chicks to Newcastle disease virus could reflect incomplete development of their immune system, partial expression or regulation of its genetic control [58] and possible variation among genotypes in the maternal effect [59]. Also chicks from immunized parents possess high level of maternally derived antibody which protects against virulent vaccines [60]. Hamal et al., [61] reported approximately 30% maternally derived antibody transfer from breeder hen to their progenies. High level of maternally derived antibody also protects and neutralizes vaccine viruses if the chicks are vaccinated [62]. The lowest maternally derived antibody (MDA) against Newcastle disease in frizzle feather chickens observed in this study was in agreement with the findings of Adeleke et al., [63] and Adebambo et al., [64] who also reported lowest MDA to Newcastle disease in frizzle feather chicken using ELISA.

The birds inoculated with 0.2ml Newcastle Disease (ND) challenged virus showed signs of infection on day 3 after inoculation with initial evidence of loss of weight. Challenged birds lost between 50 and 150g before death. Mortality rates between day 7 and 21 were 77% in Normal feather, day 7 and 21 were 100% for Frizzle feather and the mortality rate between day 7 and 28 were 57% for Naked neck respectively.

The lowest body weight was observed in frizzle feather chickens at day 14, the highest body weight observed in the genotypes at day 7 and 14 suggested growth between days 21 to 42. There were no significant differences in body weight of all the three genotypes at days 7, 21, 28, 35 and 42, and this indicates that the three genotypes performed alike in the above mentioned days.

The presence of SNP in exon 3 of ROBO2 gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens was a good indication that the region is polymorphic. The SNP identified in exon 3 of ROBO2 in was a synonymous mutation which is not expected to cause any amino acid variation. Although this SNP is not expected to have effect on protein function, Kimchi-Sarfaty et al., [65] reported that synonymous mutations have effect on disease. Silent mutations are now widely acknowledged to be able to cause changes in protein expression, conformation and function. In the sequence, at position 98 where the SNP occur shows that all Cs from the samples sequenced turned As except samples NN18, FF174 and FF135. The 98A>C SNP changes were synonymous mutation which is identified in exon 3 of ROBO2 gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens, therefore, it doesn’t affect the codon, protein or the amino acid.

However, these changes may affect ROBO2 gene expression due to codon or through other mechanisms. Another study indicated that naturally occurring silent SNP may alter gene function by affecting translation due to codon bias and can further affect in vivo protein folding, mRNA stability, or transcription [65]. In addition, this SNP may have no effect but instead may be in linkage disequilibrium with a cis-regulatory mutation.

The haematological parameters of chicken are significance to reflect inherent genetic differences amongst the breeds of chicken [66]. The variation in the haematological parameters between strains in somesituation might be due to season, species, immune system, and poor nutrition especially protein deficiency [51,67]. The variation in this study might be due to strains and genotype differences since allthe cocks are exposed to the same environment.

El-Safty et al., [37] reported the superiority of the naked neck gene in PCV compared to that of the fully feathered. The author further stated that this could be a boost to the growth and productive life of the former. Haematological and serum biochemical values could be utilized in crossbreeding programmes in order to produce individuals that are fit and more productive [68]. Genetic differences exist in all farm animals which lead to variability in the reproductive and performance abilities of animals both within, and between breeds. Differentiating this variability could be a basis for selection and subsequent genetic improvement of farm animals. Biochemical polymorphism study is one way of delineating genetic variation in animals [69]. This information may aid selection of superior animals within and between breeds for genetic improvement of desired traits [70]. Since the main goal in animal breeding is to select individuals that have high breeding values for traits of interest as parents to produce the next generation and to do so as quickly as possible [71]. Haematological parameters might be used as a tool for selection.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Conclusion

From the results obtained from this study, it can be concluded that:

- The live-weight changes in naked neck subsequently increased by day 35 and 42 post infection and that of the normal feather had same sequential result.

- The results revealed that normal feather had 94% mortality, frizzle feather 100% and naked neck 79%respectively.

- Haematological parameters revealed significant effect within and between individual genotypes of Nigerian indigenous chickens to experimental Newcastle infection with varying significant values.

- Antibody titre response was significantly highest (p<0.05) in NN followed by NF and FF. One SNP (98C>A) was identified in exon 3 of theROBO2gene in Nigerian indigenous chickens.

- SNP and haematological indices had no significant association implying that other important factors that can influence haematological parameters and antibody titre should be determined.

- Vaccination impacted better resistance NN on the strains of Nigerian indigenous chickens. With NN showing better resistance, it should be encouraged even in the backyard farming.

- ROBO2 gene had only one SNP at 98C>A in exon 3 of which it was synonymous, therefore, plays no role in the resistance of Newcastle Disease in chicken.

- The SNP was identified in the chromatogram using Bioedit, at the position 98 in the aligned sequence, the reference sequence (exon 3 of ROBO2 gene) having ‘C’ which is the original nucleotide. A sample of the Naked neck and Frizzle feather genotypes were associated with the same nucleotide ‘C’.

- The results demonstrated that genetic variation at the exon 3 of theROBO2 gene plays a key role in the immune response to Newcastle disease virus, and SNP 98C>A can be used as genetic markers for the selection of chickens with stronger immune responses to Newcastle disease virus.

Recommendations

- The present study revealed that unvaccinated Nigerian indigenous chicken genotypes possess no natural resistance against Newcastle disease virus. Vaccination against Newcastle disease is therefore recommended to cub the losses to this disease in the Nigerian indigenous chickens.

- The naked neck Nigerian indigenous chicken had better ability to secret Acute Phase Protein (APP) by liver cells, which gives protection to the chickens against infection or any invasion.

- Periodic monitoring of the antibody levels against these diseases in poultry birds, with emphasis on pre-vaccination and post-vaccination antibody levels needed to determine optimal timing for vaccination schedule in individual flocks at different locations.

- Performance of serologic profiling of day-old chicks at hatcheries in order to determine optimal schedule for batch vaccination.

- Naked neck chickens can be used to facilitate genetic improvement against Newcastle disease.

- There is need for effective extension services to farmers on ND and AI biosecurity measures in Nigeria and its environs for teamwork in efforts to control these diseases.

References

- Bearse GE, McClary CF, Miller MW (1939) The results of eight years’ selection for disease resistance and susceptibility in white Leghorns. Poultry Science 18: 4000-4401.

- Bumstead N (1996) Genetic resistance to avian viruses. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epizoot17: 249-255.

- Bacon LD, Hunt HD, Cheng HH (2000) A review of the development of chicken lines to resolve genes determining resistance to diseases. Poultry Scienc 79: 1082-1093.

- Ugochukwu EI (1982) Post vaccination Newcastle disease outbreak. Nigerian Veterinary Journal 11: 24-28.

- Hawken RJ, Beattie CW, Schook LB (1998) Resolving the genetics of resistance to infectiousdiseases. Revised Science Technology Of International Epizoot 17: 17-25.

- Doyle TM (1927) A histherto unrecorded disease of fowls due to a filter-passing virus. J comp Pathology Therapy 40: 144-169.

- Hill HD, Davis OS, Wilde JE (1953) Newcastle disease in Nigeria. British Veterinary Journal 109: 381-385.

- Okeke EN, Lamorde AG (1988) Newcastle disease and its control in Nigeria. In: Williams AO, Masiga WN (eds.). Viral Diseases of Animals in Africa. CTA/OAU/STRC Publications Lagos, Nigeria.

- Nawathe DR, Majiyagbe KA, Ayoola SO (1975) Characterization of Newcastle disease virus isolates from Nigeria. Bulletin Office International des Epizooties 83:1097-1105.

- Adu FD (1985) Characteristics of Nigerian strains of Newcastle disease virus. Avian Diseases 29: 849-851.

- Alexander DJ (2001) Newcastle Disease. The Gordon Memorial Lecture. British Poultry of Science, UK.

- Gomez-Lillo M, Bankosky RA, Wiggins AD (1974) Antigenic relationship among viscerotropic and domestic strains of Newcastle disease virus. American Journal of Veterinary Research 35: 471-475.

- Capua I, Scacchia M, Toscani T, Caporale V (1993) Unexpected isolation of virulent Newcastle disease virus from commercial embryonated fowls´ eggs. Journal of Veterinary Medicine 40: 609-612.

- Pospisil Z, Zendulkova D, Smid B (1991) Unexpected emergence of Newcastle disease virus in very young chicks. Acta Vet Brno 60: 263-270.

- FAO (2010) Chicken genetic resources used in smallholder production systems and opportunities for their development, by P. Sorensen. FAO, Rome, Italy.

- RIM (1992) Nigerian livestock resources: National synthesis, Annex Publ. Resource Inventory Management Ltd, Nigeria.

- Yakubu A, Kuje D, Okpeku M (2009) Principal components as measures of size and shape in Nigerian indigenous chickens. Thai Journal of Agricultural Science 42: 167-176.

- Oluyemi JA, Longe GO, Songu T (1982) Requirement of the Nigerian indigenous fowl for protein and amino acids. Ife Journal of Agriculture 4: 105-110.

- Wales AD, Davies RH (2011) A critical review of Salmonella typhimurium infection in laying hens. Avian Pathology 40: 429-436.

- Ogie AJ, Salako EA, Emikpe BO, Elizabeth AA, Adeyemo SA, et al. (2012) The possible genetic influence on the susceptibility of exotic, fulani and yoruba ecotype indigenous chickens to experimental Salmonella enteritidis. Livestock Research for Rural Development 24: 193.

- Prasad A, Paruchuri V, Preet A, Latif F, Ganju RK (2008) Slit-2 induces a tumor suppressive effect by regulating betacatenin in breast cancer cells. Journal of Biology Chem 283: 26624-26633.

- Ikeobi CON, Godwin VA (1990) Presence of the polydacty1 gene in the Nigerian local chickens. Tropical J Animal Sci 1: 57-65.

- Allan WH, Gough RE (1974) A standard haemagglutination inhibition tests for Newcastle disease (1) A comparison of macro and micro methods. Veterinary Record 95: 120-123.

- Dacie JV, Lewis SM (1995) Practical haematology. Churchill Livingstone Edinburg, London, UK.

- Baker FJ, Silverton RE (1985) Introduction to Medical Technology. Butterworth and Co Publishing Company 523-531.

- Jain NC (1986) Schalm’s veterinary haematology. Lea and Fabinger, Philadelphia, USA.

- Ritchie BW, Harrison JG, Harrison RL (1994) Avian Medicine. Winger’s Publishing, Inc., Florida, USA.

- Schneider RG (1973) Developments in laboratory Diagnosis, Sickle cell Disease-Diagnosis, Management, Education and Researh. St. Lovis, USA.

- Wang Y, Wang J, Li BH, Qu H, Luo CL, et al, (2014) An association between genetic variation in the roundabout, axon guidance receptor, homolog 2 gene and immunity traits in chickens. Poultry Science 93: 31-38.

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ (1994) CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Research 22: 4673-4680.

- SAS (1999) SAS User Guide: Statistical Analysis Institute. Cary. North Carolina, USA.

- SAS (2002) SAS guide: Statistics released version 9.0. Statistical analysis system institute inc., Cary, NC, USA.

- Yonash N, Cheng HH, Hillel J, Heller DE, Cahaner A (2001) DNA microsatellites linked to quantitative trait loci affecting antibody response and survival rate in meat-type chickens. Poultry Science 80: 22-28.

- Msoffe PLM, Mtambo MMA, Minga UM, Gwakisa PS, Mdegela RH, et al. (2002) Productivity and NaturalDisease Resistance Potential of Free-ranging Local Chicken Ecotypes in Tanzania. Livestock Research for Rural Development 14.

- Fayeye TR, Ayorinde KL, Ojo V, Adesina DM (2006) Frequency and influence of show major genes on body weight and body size parameters of Nigerian local chickens. Livestock Researchand Rural Development 18: 1-9.

- Akinoluwa PO, Salako AE, Emikpe BO, Adeyeo SA, Ogie AJ (2012) The Differential Susceptibility of Yoruba Ecotype Nigerian Indigenous Chicken Varieties to Newcastle Disease. Nigerian Veterinary Journal 33: 427-429.

- El-Safty SA, Ali UM, Fathi MM (2006) Immunological parameters and laying performance of naked neck and normal feathered genotypes of chickens under winter condition of Egypt. International Journal Poultry Science 5: 780-785.

- OIE (2012) Newcastle disease. Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals. OIE, France.

- Brattt MA, Clavell LA (1972) Heamolytic interraction of Newcastle diseases virus and Chicken erythrocytes. 1. Quantitative comparison procedure. Applied Microbiology 23: 454-460.

- Oladele SB, Nok AJ, Esievo KA, Abdu P, Useh NM (2005) Haemagglutination Inhibition Antibodies, Rectal Temperature and Total Protein of Chickens Infected with a Local Nigerian Isolate of Velogenic Newcastle Disease Virus. Veterinary Research Communications 29: 171-179.

- Alexander DJ (1997) Newcastle disebase and other paramyxovirus Iowa State University Press 541-569.

- Hassan MK, Afify MA, Aly MM (2004) Genetic Resistance of Egyptian Chickens to Infectious Bursal Disease and Newcastle Disease. Tropical Animal Health and Production 36: 1-9.

- Morgan-Caprar T, Bryden A (1998) Newcastle disease in Zoonoses. Oxford, UK.

- Biscarini F, Bovenhuis H, Arendonk JA, Parmentier HK, Jungerius AP, et al. (2010) Across-line SNP association study of innate and adaptive immune response in laying hens. Animal Genetics 41: 26-38.

- Spradbraw PB (1988) Geographical Distribution of Newcastle Disease. In: Alexander DJ (Ed.). Newcastle Disease, Kluwer Academic Publishers, USA.

- Alexander DJ (1991) Newcastle disease vaccines and other paramyxovirus infections. In: Calnek BW (Ed.). Diseases of Poultry. Iowa state university press, Iowa, USA.

- Ekue FN, Pone KD, Mafeni MJ, Nfi AN, Njoya J (2002) Survey of the Traditional Poultry Production System in the Bamenda area, Cameroon. FAO/IAEA, Nigeria.

- Mai HM, Ogunsola OD, Obasi OL (2004) Serological survey of the Newcastle disease and Infectious Bursal disease in local ducks and local guinea fowls in Jos, Plateau state, Nigeria. Revue Elev Med Vet Pays trop 57: 41-44.

- Pitcovski J, Cahaner A, Heller ED, Zouri T, Gutter B, et al. (2001) Immune response and resitance to infectious bursal disease virus of chicken lines selected for high or low antibody response to Escherichia coli. Poultry Science 80: 879-884.

- Gross WG, Siegel PB, Hall RW, Domermuth CH, DuBoise RT (1980) Production and persistence of antibodies in chickens to sheep erythrocytes: Resistance to infectious diseases. Poultry Science 59: 205-210.

- Oladele SB, Ogundipe S, Ayo JO, Esievo KAN (2001) Effects of season and sex on packed cell volume,haemoglobin and total protein of indigenous pigeons in Zaria, Northern Nigeria. Veterinarski Arhiv 71: 277-286.

- Spanoghe L, Peeters JE, Cotlear JC, Devos AH, Viaene N (1977) Kinetics of serum and local haemagglutination antibodies in chicken following vaccination and experimental infection with Newcastle disease virus and their relation with immunity. Avian Pathology 6: 101-109.

- Fathi MM, Galal A, El Safty SA, AbdEf-Fatah S (2005) Impact of naked neck and frizzle genes on cell-mediated immunity of chicken. Egyptian Poultry Science 25: 1055-1067.

- Fathi MM, El-Attar AH, Ali UM, Nazmi A (2008) Effect of the naked neck gene on carcass composition and immunocompetence in chicken. British Poultry Science 49: 103-110.

- Galal A (2008) Immunocompetence and some haematological parameters of Naked neck and normally feathered chicken. Journal of Poultry Science 45: 89-95.

- Rajkumar V, Reddy BLN, Rajaravindra KS, Niranjan M, Bhattaacharya TK, et al. (2010) Effect of naked neck gene on immune competence, serum biochemical and carcass traits in chicken under a tropicalclimate. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Science 23: 867-872.

- Yonash N, Leitner G, Waiman R, Heller ED, Cahaner A (1996) Genetic differences and heritability of antibody response to Escharicia coli vaccination in young broiler chicks. Poultry Science 75: 683-690.

- Sacco RE, Nestor KE, Saif YM, Tsai HJ, Anthony NB, et al. (1994) Genetic analysis antibody response of turkeys to Newcastle disease virus and Pasteurellamultocida vaccines. Poultry Science 73: 1169-1174.

- Leitner G, Gutman M, Heller ED, Yonash N, Cahaner A (1994) Parent effect on the humoral immune response to Eschericia coli and Newcastle disease virus in young broiler chicks. Poultry Science 73: 1534-1541.

- Rahman MM, Bari ASM, Giusuddin M, Islam MR, Alam J, et al. (2002) Evaluation of maternal and humoral immunity against Newcastle disease virus in chicken. International Journal of Poultry Science 1: 161-163.

- Hamal KR, Burgess SC, Pevzner IY, Erf GF (2006) Maternal antibody transfer from dams to their egg yolks, egg whites and chicks in meat lines of chickens. Poultry Science 85: 1364-1372.

- Awan MA, Otte MJ, James AD (1994) The epidemiology of Newcastle disease in rural poultry. Avian Pathology 23: 405-423.

- Adeleke MA, Peters SO, Ogunmodede DT, Oni OO, Ajayi OL, et al. (2015) Genotype effect on distribution pattern of maternally derived antibody against Newcastle disease in Nigerian local chickens. Tropical Animal Health and Production 47: 391-394.

- Adebambo OA, Ikeobi CON, Ozoje MO, Oduguwa OO, Adebambo OA (2011) Combination abilities of growth traits among pure and crossbred meat type chickens. Archivos Zootecnia 60: 953-963.

- Kimchi-Sarfaty C, Oh JM, Kim IW, Sauna ZE, Calcagno AM, et al. (2007) A “silent” polymorphism in the MDR1 gene changes substrate specificity. Science 315: 525-528.

- Agaie BM, Uko OJ (1998) Effect of season, sex, and species difference on the packed cell volume (P.C.V.) of Guinea and domestic fowls in Sokoto, Sokoto state of Nigeria. Nigerian Veterinary Journal 19: 95-99.

- Adejumo DO (2004) Haematological, growth and performance of broiler finisher fed ration supplement with Indian almond (Terminaliacatappa) husk and kernel meal. Ibadan Journal of Agricultural Research, Nigeria.

- Ladokun AO, Yakubu A, Otite JR, Omeje JR, Sokunbi JN, et al. (2008) Haematological and Serum Biochemical Indices of Naked Neck and Normally Feathered Nigerian Indigenous Chickens in a Sub Humid Tropical Environment. International Journal of Poultry Science 7: 55-58.

- Egena SSA, Aloa RO (2012) Haemoglobin olymorphism in selected farm animals-a review. Biotechnology in Animal Husbandry 30: 377-390.

- Bibinu BS, Yakubu A, Ugbo SB, Dim NI (2016) Computational Molecular Analysis of the Sequences of BMP15 Gene of Ruminants and Non-Ruminants. Open Journal of Genetics 6: 39-50.

- Dekkers JC (2012) Application of Genomics Tools to Animal Breeding. Current Genomics 13: 207-212.

Citation: Japhet YB, Ozoje MO, Ilori BM, Sonibare AO (2025) Analysis of ROBO2 Gene and response of Three Genotypes of Nigerian Indigenous Chicken to Experimental Newcastle Disease Virus Infection. HSOA J Genet Genomic Sci 10: 051.

Copyright: © 2025 Yeigba B Japhet, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.