Ask - Adapt - Collaborate: An Approach to Individualizing Acute Care for People with Dementia

*Corresponding Author(s):

Kathleen DragoDivision Of General Internal Medicine & Geriatrics, Oregon Health & Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd L475, Portland, OR 97239, United States

Tel:+1 5034947967,

Email:drago@ohsu.edu

Abstract

People with dementia comprise a growing share of the hospital patient population, often receiving care in medical, surgical and critical care units as opposed to behavioral health settings. Dementia confers a greater reliance on familiar people, stimuli and surroundings to support physical and cognitive function. Hospital stays disrupt this critical support and too often lead to long lasting declines in independence, physical functioning and cognitive abilities. Inpatient ACE (Acute Care for Elders), MACE (Mobile Acute Care for Elders) and geriatrics consult programs across the country have shown that adapting inpatient care to the unique needs of cognitively impaired patients can improve hospital and post-hospital outcomes. These programs and specialists are not widespread but hospitalists can easily incorporate some of their practices into usual care, individualizing and adapting care for each person with dementia. The Ask-Adapt-Collaborate model incorporates patient-centered dementia care and interdisciplinary collaboration into typical hospitalist daily workflows.

Keywords

Dementia; Geriatrics; Patient centered care

Introduction

Meet Lucy …

Lucy is an 82 year-old Colombian born woman living in the US for 50 years, with macular degeneration and moderate stage dementia. She lives with her husband, daughter, son in law and two grandsons. She is admitted to the hospital with abdominal pain, nausea and 35-pound weight gain due to acutely decompensated heart failure and atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rate. She has no recollection of her arrival at the hospital, believing we are in her home, and is constantly searching for her son. Diuresis is causing her incontinence. When she is incontinent, Lucy searches for the bathroom, causing the unit staff to add alarms, block the bathroom door and request antipsychotics for “impulsivity”. She is wearing briefs and reassured that she can “just go”, but she still searches for the bathroom.

At night she calls out for her family in Spanish. After 2 days, she refuses to get up from bed and requires two-person assist to stand. She has only eaten one meal a day since admission. Two weeks later in post-acute rehab, Lucy continues to lack motivation to get up during the day and is still requiring one person and a walker to transfer. She spends most of her days in a wheelchair. Situations like Lucy’s are all too common, resulting in long lasting effects for patients and caregivers. People with dementia are at 1.4 times higher risk for hospital admission, typically for acute medical illness rather than psychiatric conditions [1] and make up a growing share - approximately 30% - of the hospital population [2]. Though every person’s experience with dementia is different, they all are uniquely vulnerable to the typical standards and practices of hospital care.

Dementia makes people more reliant on their familiar environments and routines to navigate a regular day. Nothing about a day in the hospital, however, is familiar. The most basic features of hospital life - activity and noise all day and night, restrictions to normal movement, roommates and repeated contact with strangers - become significant sources of confusion and distress. Layer on top of this treatment specific medical devices that easily become tethers (i.e., telemetry, IV lines, catheters), care that occurs on our schedule instead of the patient’s and under-diagnosis or dismissal of diagnoses because of atypical presentations [2]. Even short hospital experiences can range from disorienting to traumatic. For some patients, a short hospital stay can trigger a cascading decline in function that may not be recoverable with rehab [2]. Hospitalists and acute care interprofessional teams are on the front lines of the need for individualized dementia-friendly acute care. Awareness of this need is expanding beyond providers to policy makers, resulting in governmental efforts to ensure that people with dementia receive the individualized care they need to thrive.

Massachusetts state law requires health systems, including acute care, to develop plans to meet the needs of patients with dementia by October 2021 [3]. The goal of individualized, dementia-friendly acute care is necessary and attainable. Acute Care for Elders (ACE) units and Mobile ACE teams across the country have shown that individualized geriatric care can shorten time spent in the hospital and preserve function. They often, however, require geographic cohorting and a dedicated specialized admitting team and can be resource intensive despite being cost neutral [4-8].

This same approach, which was adapted specifically for inpatients with cognitive impairment at Northwell Health, showed that individualized dementia care delivered by existing but trained care teams can reduce length of stay and in house mortality in addition to improving physical restraint use, high risk medications and NPO orders [9]. While the Northwell Health experience may be more attainable for some, it still depends on structural and personnel investments that may be difficult for hospitals and health systems to deploy. People with dementia develop acute surgical conditions, critical illness and neurologic conditions that will rightfully triage their care to specialized units, limiting the reach of any fixed unit and staff-based intervention. Inpatient geriatrics consult teams offer similar expertise and patient outcomes with leaner structural investments and greater flexibility to reach patients where they are [10,11]. Inpatient geriatrics consult teams along with ACE and MACE teams, are still novel and less available outside of academic medical centers than the need suggests.

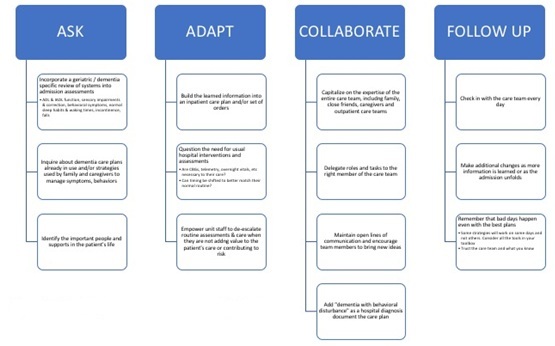

What can hospitalists and other inpatient providers do now to individualize their care for people with dementia? [Figure 1].

Figure 1: Ask - Adapt - Collaborate - Follow up model.

Figure 1: Ask - Adapt - Collaborate - Follow up model.

The Ask-Adapt-Collaborate Model offers a simple framework for investigating and incorporating a person-centered care approach into standard hospital care for those living with dementia. This approach meshes into standard work for hospital providers and can be adopted easily by providers regardless of training.

What could this approach mean for Lucy?

Lucy is an 82 year-old Colombia born woman living in the US for 50 years, with macular degeneration and moderate stage dementia. She lives with her husband, daughter, son in law and 3 grandsons. Her family manages all of her IADLs and cue her to dress and bathe. She is able to use the bathroom on her own without incontinence and self feed but her daughter Rita has been providing more reminders and supervision for her other ADLs in the last 6 months. Lucy often forgets to put on her glasses and leaves them in various places around the house. It is common for her to be disoriented, often believing she is in her childhood home, and slip into speaking Spanish despite primarily speaking English for 50 years. She is a retired music teacher and still loves to listen to music and sing. She wakes up at almost every night and will walk around several times believing she has chores to finish.

Lucy is admitted to the hospital with abdominal pain, nausea and 35 pound weight gain due to acutely decompensated heart failure and atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rate. Her family brought her favorite sweater and photos of her grandchildren. Unit staff made her a cord for her glasses to hang around her neck when she takes them off. The admitting hospitalist and nurse discuss telemetry and IV access, deciding on intermittent vitals Q2 for 8 hours followed by Q4. The peripheral IV for diuresis is placed in her upper arm so it is easier to cover with clothes. Lucy believes she is either in her music room at school or in her childhood home and staff do not challenge these beliefs. Instead, they comment on what nice places they are, causing Lucy to smile and tell stories about her childhood and former students. A few of the nurses and physical therapists speak Spanish with her and encourage Lucy to sing some of her favorite songs during therapy sessions and personal care, reducing fear and anxiety.

After her first dose of diuretic, nursing staff begin scheduled voiding every 2 hours during the day to maintain continence and reduce distress from urinary urgency. Lucy is able to recognize the bathroom due to the picture of a toilet taped to the door and is able to maintain continence throughout her stay. When she wakes up at night, aides help her to the bathroom and, if she wants to walk around, they walk in the hallways with her until she fatigues. Her family helps choose her meals and snacks and unit staff pre-order from the kitchen for 2-3 days at a time. Lucy always has something readily available when she’s hungry and unit staff note that she usually finishes everything offered to her. She hasn’t had any curiosity about the peripheral IV as long as she is wearing her favorite sweater.

Lucy spends a total of 7 days in the hospital and is able to discharge home with her family and a home health RN to continue heart failure education for her family caregivers. A few targeted questions, interdisciplinary knowledge and some creativity can help people with dementia thrive through acute illness and elevate the joy in caring for these patients and their families.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure

I have no industrial or financial conflicts of interest.

References

- Shepherd H, Livingston G, Chan J, Sommerlad A (2019) Hospitalisation rates and predictors in people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medicine 2019 17: 130.

- George J, Long S, Vincent C (2013) How can we keep patients with dementia safe in our acute hospitals? A review of challenges and solutions. J R Soc Med 106: 355-361.

- Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association (2018) Guidance for developing an operational plan to address diagnosis and care for patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in hospital settings. MHHA, Massachusetts, USA.

- Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, Fortinsky RH, Kowal J (1995) A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med 332: 1338-1344.

- Counsell SR, Holder CM, Liebenauer LL, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. (2000) Effects of a multicomponent intervention on functional outcomes and process of care in hospitalized older patients: Arandomized controlled trial of Acute Care for Elders (ACE) in a community hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc 48: 1572-1581.

- Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR, Wieland GD, English PA, Sayre JA, et al. (1984) Effectiveness of a geriatric evaluation unit. A randomized clinical trial. N Engl J Med 311: 1664-1670.

- Hung WW, Ross JS, Farber J, Siu AL (2013) Evaluation of the Mobile Acute Care of the Elderly (MACE) service. JAMA Intern Med 173: 990-996.

- Farber JI, Korc-Grodzicki B, Du Q, Leipzig RM, Siu AL (2011) Operational and quality outcomes of a mobile acute care for the elderly service. J Hosp Med 6: 358-363.

- Sinvani L, Warner-Cohen J, Strunk A, Halbert T, Harisingani R, et al. (2018) A Multicomponent Model to Improve Hospital Care of Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 661: 1700-1707.

- Bernstein JM, Graven P, Drago K, Dobbertin K, Eckstrom E (2018) Higher quality, lower cost with an innovative geriatrics consultation service. J Am Geriatr Soc 66: 1790-1795.

- Schubert CC, Parks R, Coffing JM, Daggy J, Slaven JE, et al. (2019) Lessons and outcomes of Mobile Acute Care for Elders consultation in a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. J Am Geriatr Soc 67: 818-824.

Citation: Drago K (2021) Ask - Adapt - Collaborate: An Approach to Individualizing Acute Care for People with Dementia. J Gerontol Geriatr Med 7: 108.

Copyright: © 2021 Kathleen Drago, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.