Association of Loneliness, Social Isolation and Daily Cognitive Function in Mexican Older Adults Living in Community during the First Wave of COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown

*Corresponding Author(s):

Sara Gloria Aguilar-NavarroDeparment Of Geriatric Medicine And Neurology Fellowship, Instituto Nacional De Ciencias Medicas Y Nutricion Salvador Zubiran, Tlalpan, Mexico City, Mexico

Tel:+52 5554166463, 5710

Email:sara.aguilarn@incmnsz.mx

Abstract

Loneliness and social isolation are known risk factors for cognitive decline; their effect in Older Adults (OA) after COVID-19 lockdown is emerging.

Objective: To establish an association between loneliness and social isolation, with daily cognitive function in Mexican OA during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: Cross-sectional study, daily cognitive function was determined with the Everyday Cognition Scale (E-Cog). Loneliness and social isolation were binomial variables.

Results: The mean age was 65.4 ± 7.9 years, 75.7% were women. The mean E-Cog was 57.4 (SD: ± 19.1). Eighty four percent of participants reported loneliness, 79.9% reported social isolation. Multivariate regression model showed a positive and statistically significant association between loneliness and E-Cog, adjusted by age, sex and education level (β: 0.41, 95% CI: 0.22-0.38, p: <0.01).

Conclusion: These data suggest the need for increased vigilance of those who have loneliness due to its potential deleterious effect on cognitive function.

Keywords

Cognitive performance; COVID-19; Loneliness; Older adults; Social-isolation

Introduction

The pandemic caused by SARS-CoV2, the etiologic agent of COVID-19, represents an unprecedented social and health emergency. In Mexico, according to data from the World Health Organization, as of January 2022, there have been 4, 258, 2836 accumulated cases and 313,479 deaths related to COVID-19 since the pandemic began. Lockdown started on March 23rd, 2020, and it extended over a year, with a peak (average number of infections per day) on January 20th, 2021 [1]. Since Older Adults (OA) are particularly susceptible to develop severe manifestations of the disease and complications that increase disability and decrease quality of life [2], it was a priority that this population sector remains isolated as an effective prevention strategy; however, this represented a new challenge for older adults’ mental health. At this point, two different terms must be introduced: a), Social isolation, which is defined as having few social contacts and little commitment to others and the community in general [3], b), Loneliness, which refers to the adverse emotional state experienced subjectively related to the perception of unsatisfied intimate and social needs [4].

Prevalence suggests that nearly one-third of older adult’s experience loneliness and/or social isolation, and a subset (5%) reports often or always feeling lonely [5]. Although loneliness does not have the status of a clinical disease by itself, it is associated with several negative health outcomes like stress, sleep disturbances, depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment, coronary heart disease, stroke and mortality [6].

On the other hand, partial or total restriction of social interaction could generate negative consequences for the health of OA, especially in those with chronic diseases, disabilities and geriatric syndromes [2]. Social isolation may cause impairment in social recognition memory, thereby potentially increasing risk of long-term perceptions of loneliness (i.e., animals exposed to social isolation later have difficulties with social recognition) [7]. However, it does not affect other types of memory. This may be related to the specific neural network which processes social information in the mammalian brain which includes: olfactory bulbs, medial nucleus of the amygdala, lateral septum and the pyramidal layer of neurons of the hippocampus which makes a trajectory in the shape of an inverted C, specially in the region called CA2 [8].

We aim to examine the influence of loneliness and social isolation in daily cognitive function in a sample of Mexican older adults living in the community during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown and assess characteristics associated with loneliness.

Materials and Methods

Design and sampling

Cross-sectional study derived from the cohort “The impact of COVID 19 on well-being, cognition, and discrimination among older adults in the United States and Latin America.” carried out in a population of non-institutionalized people aged 55 or older. A non-probabilistic sampling was performed, selecting, for convenience, those in the United States, as well as several in Spanish and Portuguese-speaking countries of Latin America. A detail description of the methodology is summarized in the study by Ganesh M, et al., [9].

Participants

For this study, we included participants who resided in Mexico (n = 308), during the first six months of lockdown (March-August 2020).Those who completed the previously described surveys in the first stage or baseline of the SARS-CoV2 pandemic were chosen. All participants completed a one hour-long survey (online with a computer or smartphone or through a phone call with a trained researcher, for help) which was conducted in Spanish. Collected data were managed using the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tool, a software designed for the research data capture which is located at the Massachusetts General Hospital [10]. All measurements were translated to Spanish following the World Health Organization guidelines to ensure accuracy.

Dependent variable

Systematic assessment of daily cognitive function offers the potential to improve our understanding of the determinants of functional decline, specific cognitive impairments, [11] mild changes in daily function and daily cognition frequently occur in the early stages of neurodegenerative diseases of aging, including during the stage of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) [12]. Thus we assessed them with the Everyday Cognition Scale (E-Cog). This instrument has been designed to subjectively assess cognitive and functional abilities, an improvement if compared to its performance 10 years ago. It exhibits excellent psychometric properties including good test-retest reliability (r = 0.82, p <0.001). It also provides evidence of various aspects of validity such as content and construction as well as convergent, divergent and external validity. E-Cog comprises 39 items through which six cognitive domains are evaluated, and they are: memory, language, visuospatial and perceptual skills, planning, organization and divided attention. Each item is rated using a four-point Likert scale that ranges from 1: better or no change, to 4: consistently much worse (Table 1 in the supplement) [13]. Each functional domain was defined by the underlying cognitive abilities thought to be the most critical to those daily living activities, higher score indicates greater deterioration [14].

Additionally, it has been proposed as an instrument to assess Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD): Any occasion SCD = any item scored ≥2, but none ≥3; any consistent SCD = any item scored ≥3 [15]. The suggested cutoff point based on a cross-sectional comparison of the ADNI cutoff to discriminate between normal cognition and cognitive impairment is 1.31 for the participant and 1.36 when applied to the informant (iECog). However, this score has not yet been validated in mexican population [16].

Independent variable

Loneliness: The De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale [17] measures emotional (items 1, 5 and 6) and social loneliness (items 2, 3 and 4) by three items each, with a total of six items for general loneliness. Participants select an answer from four options which are: “yes”, “more or less”, “no” or “no answer”. Negatively worded items were inverted; afterward these item scores were added to obtain a total for each participant. Higher scores indicate greater loneliness (Table 2 in the supplement).

Social isolation: The Epidemic-Pandemic Impacts Inventory (EPII) [18] is a questionnaire developed and designed to assess the personal impact of the coronavirus pandemic in various domains of personal and family life. The EPII consists of 92 items in 10 categories that assess employment (11 items), education (2 items), home life (13 items), social activities (10 items), economy (5 items), emotional health and well-being (8 items), physical health (8 items), physical distancing and quarantine (8 items), history of infection (8 items) and positive change (19 items). For the present study, the subscale of physical distancing and quarantine was used. The responses were summed (yes versus no), and the mean of this subscale was calculated. A higher number in the score suggests a higher load/difficulty (Table 3 in the supplement).

Subjective memory complain: The 7-Memory questionnaire has been validated to assess cognitive changes in older people [19,20], and the answers consist of “yes” or “no” according to the subjective memory complaint. The responses were summed to obtain a maximum score of 7. Higher scores represent a greater subjective memory complaint (Table 4 in the supplement).

Sociodemographic and clinical variables

Information on age, gender, marital status, educational level by years of education, occupation, self-perception of health status, self-reported comorbidities and the use of medications were included. In addition, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (modified from 2010) was calculated to classify comorbidity as mild (1-3), moderate (4-6), and severe (greater than 6) [21,22].

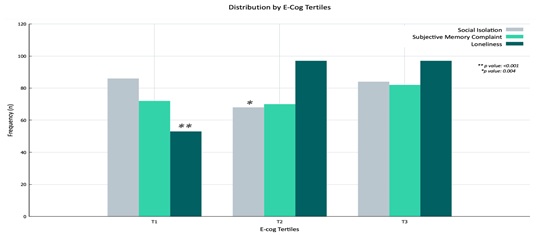

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics using arithmetic means, standard deviations, frequencies and proportions examined in sociodemographic and health variables was performed. The presence of loneliness, social isolation and subjective memory complaint were binomial variables. rho Spearman correlations were examined to establish the relationship between the E-Cog total score as well as the outcome measures. In order to determine the association between loneliness, isolation with E-Cog, univariate linear regression models were constructed using normalized E-Cog global score by Natural Logarithm (Ln) which were later adjusted for potentially confounding variables (age, sex and education) on multivariate linear regression. In addition, to search for an association between the binomial variables previously described, the participants were categorized into tertiles of the global E-Cog score with the following ranges: Tertile 1 (T1): 37.46 -46; Tertile 2 (T2): 46.01-58 and Tertile 3 (T3): 58.01 or more and were compared using ANOVA. A value of p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25.0 for MAC (Chicago, IL, USA), figures were made with RStudio (R version 4.1.0, RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA).

Results

From a total of 308 participants, 4 participants were excluded for incomplete surveys. Finally, 304 participants were included for statistical analysis from which75.7% were women (n = 233) with a mean age of 65.4 years (SD: ± 7.9), only 8.4% reported COVID-19 symptoms. Most subjects were married/civil union (48.7%). Those who lived alone were distributed within the following groups: single (17.2%), widowed (14.6%), and divorced/living alone (19, 48%). The average years of education was 15 (SD: ± 3.0). In terms of occupation, most participants were retired (33.1%), followed by economically active people (25.9%) and housewives (21.3%) (Table 1).

|

Total number of participants (n) |

308 |

|

Age, years mean ± SD |

65.4 (7.9) |

|

Sex, n (%) Male Female |

75 (24.3) 233 (75.7) |

|

Education, years mean ± SD |

15 (3.0) |

|

Marital status, n (%) Single Married/civil union Divorced/living alone Widowed |

53 (17.2) 150 (48.7) 60 (19.5) 45 (14.6) |

|

Working status, n (%) Employed Unemployed Retired Housewife Other |

79 (25.9) 31 (10.2) 101 (33.1) 65 (21.3) 29 (9.5) |

|

Self-perception of health, n (%) Good Poor |

294 (95.6) 14 (4.4) |

|

Drugs, n (%) 0-4 5 or more |

301 (97.7) 7 (2.3) |

|

Charlson comorbidity index n (%) 1 - 3 4 - 6 7 - 9 Mean, SD |

241 (77.2) 61 (19.8) 9 (2.9) 2.74 (4.0) |

|

Comorbidity (n,%) |

|

|

Systemic Arterial Hypertension Diabetes Mellitus Gastrointestinal Depression Hypothyroidism |

98 (31.8) 50 (16.2) 36 (11.6) 29 (9.4) 28 (9.0) |

|

COVID-19-Symptoms (n,%) |

26 (8.4) |

Table 1: Participants sociodemographic characteristics.

Several health conditions were registered by the participants’ self-report, and they were classified based on ICD-10 [World Health Organization, 2016] diagnoses in the following categories: cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, mental health, neurological, orthopedic, renal, infectious and rheumatological. The five most frequently reported were: Hypertension (High Blood Pressure) (31.8%), Diabetes Mellitus (16.2%), Gastrointestinal (11.6%) where Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Gastritis were included, Depression (9.4%) and Hypothyroidism (9.0%). To determine the burden of comorbidity, the Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated [21,22] and classified as mild (1-3 points), moderate (4-6 points), and severe (7-9 points) comorbidity with a frequency of 77.3%, 19.8%and 2.9% respectively, with a mean of 2.7 (SD: ± 4.0) points which corresponds to moderate comorbidity. The self-perception of health was good up to 95.6% (Table 1).

Up to 84.0% (n = 259) had loneliness with a mean affirmative item in the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness scale of 4.13 (SD: ±1.1) while 79.9% (n = 246) of the participants identified themselves with social isolation using the EPII scale (Table 2). On the other hand, the E-Cog total score was 57.6 (SD: ±18.8) and average score 1.4 (SD: ±0.49) with the following highest scores for these cognitive domains: memory (14.1, SD±5.5), language (13.7, SD±5.0) and visuospatial (9.1, SD±3.1).

|

De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale |

||

|

Loneliness [n (%)] Total (mean ± SD) 1-2 3-4 5-6 |

259 (84.0) 4.13 (1.1) 12 (3.9) 154 (49.8) 93 (30.1) |

|

|

EPII Physical Distancing and Quarantine |

||

|

Social isolation [n (%)] Total positive items (mean ± SD) Self-report EPII 1-3 EPII 4-6 EPII 7-8 Other family member 1-3 4-6 7-8 |

246 (79.9) 1.99 (1.5)

180 (58.3) 55 (17.8) 2 (0.6)

139 (45) 20 (6.5) 149 (48.5) |

|

|

Everyday Cognition Scale (E-Cog) |

||

|

Cognitive domains (mean ± SD) |

Global |

Averagea |

|

Memory |

14.1 (5.5) |

1.2 (0.4) |

|

Language |

13.7 (5.0) |

1.3 (0.4) |

|

Visuospatial |

9.1 (3.1) |

1.3 (0.5) |

|

Planning |

6.3 (2.2) |

1.5 (0.72) |

|

Organization |

8.1 (3.2) |

1.7 (0.68) |

|

Divided attention |

6.2 (2.9) |

1.5 (0.49) |

|

E-Cog total scorea E-Cog Lnb |

57.6 (18.8) 4.0 (0.2) |

1.4 (0.49) |

|

Tertil 1 (37.46 - 46) 2 (46.01 - 58) 3 (58.01 or more) |

[n (%)] 24 (7.8) 33 (10.7) 245 (79.3) |

|

|

7-Memory Questionnaire |

||

|

Subjective Memory Complaint [n (%)] Affirmative items (mean ± SD) 1-3 4-7 |

226 (73.1) 2.28 (2.0) 132 (42.7) 92 (29.8) |

|

Table 2: Questionnairies.

*Average score: E-Cog global divided by the number of items of each domaing; final average score was obtained from the sum of the means of each domain divided by six.

bE-Cog Ln: Normalized E-Cog score by natural logarithm.

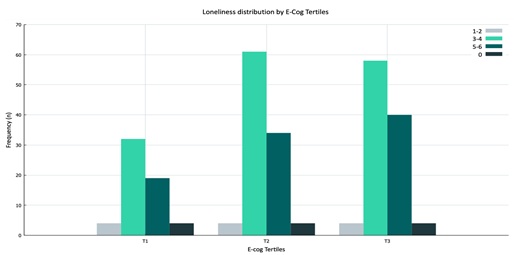

While 73.1% of the participants reported memory complaint, evidenced with affirmative items in the 7-Memory Questionnaire, the mean affirmative items were 2.2 (SD: ±2.0), and the major complaints were: in difficulty of remembering things from one second to the next (48.9%) and remembering a short list of items (43.3%). Since there is no cut-off point validation for E-Cog in Mexicans, distribution was examined by tertiles with the following ranges: Tertile 1 (T1): 37.46 -46; Tertile 2 (T2): 46.01-58 and Tertile 3 (T3): 58.01 or more (Figure 1). Those with loneliness have the higher scores (T2 and T3), while those with less perception of loneliness had a better performance on E-Cog, this results were statistically significant, (Table 3, Figure 2). Loneliness scale (rho 0.219, p<0.005) and EPII Physical Distancing and Quarantine (rho 0.178, p<0.05) showed positive Spearman correlation.

Figure 1: Distribution of participants by E-Cog tertiles.

Figure 1: Distribution of participants by E-Cog tertiles.

Lower E-Cog (T1) scores have a lower frequency of loneliness. The aquamarine bars represent loneliness in participants (at least 1 positive response in De Jong Gierveld questionnaire); gray bars represent self-reported social isolation (at least 1 positive response in EPII); green bars represent the participants with a subjective memory complaint (at least 1 positive item in the 7-Memory questionnaire). The Y-axis expresses the frequency of participants (n), the X-axis shows the score obtained in E-Cog divided by tertiles (T1: 37.46 - 46; T2: 46.01-58; T3: 58.01 or more).

|

E-Cog (score) |

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

c2 |

|

Loneliness [n (%)] |

53 (17.3) |

97 (31.8) |

97 (31.8) |

<0.001 |

|

Social Isolation [n (%)] |

86 (28.2) |

68 (22.3) |

84 (27.5) |

0.004 |

|

SMC +[n (%)] |

72 (23.6) |

70 (22.9) |

82 (26.9) |

0.21 |

Table 3: Distribution by E-Cog tertiles.

SMC: Subjective Memory Complaint

Tertil 1: 37.46 -46; Tertil 2: 46.01-58;Tertil 3: 58.01 or mores

Figure 2: Loneliness distribution of participants by E-Cog tertiles.

Figure 2: Loneliness distribution of participants by E-Cog tertiles.

Lower E-Cog (T1) scores have a lower frequency of loneliness, mean affirmative items in the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness scale was 4.13 (1.1). Bars are placed in ascending order according to the affirmative items, the darkest bar represents the participants without loneliness (0 affirmative items). The Y-axis expresses the frequency of participants (n), the X-axis shows the score obtained in E-Cog divided by tertiles (T1: 37.46 - 46; T2: 46.01-58; T3: 58.01 or more).

Using the cut-off point suggested by Van Hartel et al., 49.1% (n: 150) had a score

|

n: 305 |

E-Cog <1.31 [n: 150 (49.1%)] |

E-Cog >1.31 [n:154 (50.9 %)] |

c2 |

|

Charlson comorbidity index 0-2 3-4 5-6 7 or more |

86 (57.33) 49 (32.66) 9 (6.0) 6 (4.0) |

77 (50) 55 (35.7) 18 (11.6) 4 (2.59) |

0.24 |

|

Loneliness Affirmative items 1 2 3 4 5 6 |

110 (73.33)

12 (8.0) 36 (24.0) 28 (18.66) 16 (10.66) 8 (5.33) 10 (6.66) |

118 (76.62)

29 (18.83) 23 (14.93) 14 (9.09) 17 (11.03) 17 (11.03) 18 (11.68) |

0.09 |

|

Social Isolation Affirmative items 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

107 (71.33)

30 (20.0) 39 (26.0) 14 (9.33) 15 (10.0) 6 (4.0) 2 (1.33) 1 (0.66) |

135 (87.66)

34 (22.07) 38 (24.67) 31 (20.1) 20 (12.98) 9 (5.84) 2 (1.29) 1 (0.64) |

0.01 |

|

Subjective Memory Complaint Affirmative items 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

81 (54.0)

34 (22.66) 24 (16.0) 16 (10.66) 4 (2.66) 1 (0.66) 1 (0.66) 1 (0.66) |

139 (90.2)

15 (9.74) 17 (11.03) 26 ((16.88) 36 (23.37) 19 (12.33) 16 (10.38) 10 (6.49) |

<0.001 |

|

COVID-19 Symptoms |

10 (6.66) |

16 (10.38) |

0.24 |

Table 4: Ecog distribution with cut-off point.

Table 5 describes the multivariate regression model with normalized E-Cog score (Ln) adjusted by age, sex and education. There’s a significant relationship between the E-Cog score and participants with loneliness (β: 0.41; 95 % CI: 0.21-0.38, p<0.001), this model explains the 16.1% of the variability of the E-Cog score. In contrast, there was no association between social isolation (β: 0.01; 95 % CI: -0.067-0.88, p: 0.74). Finally, exploring the adjusted linear regression model with the cut-off point 1.31 (Table 6), we found a negative and statistically significant association with loneliness (β: -0.046; 95% CI: -0.080, -0.013; p 0.007) and isolation (β: -0.168; 95% CI: -0.089, -0.018; p 0.003), compared to SMC where a positive association with ECog was found (β: 0.812; 95% CI: -0.16, -0.11; p< 0.001).

|

|

β |

CI 95% |

p value |

|

Loneliness |

0.41 |

0.21-0.38 |

<0.001 |

|

Social isolation |

0.01 |

-0.06-0.88 |

0.74 |

|

Subjective Memory Complaint |

0.03 |

-0.51-0.90 |

0.58 |

Table 5: Association of loneliness, social isolation and subjective memory complaint with daily cognitive function multivariate regression model: E-Cog (Ln)+

Social isolation detected by EPII: physical distancing and quarantine.

Loneliness was determined with 1 or more affirmative items in the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale.

Subjective Memory Complaint was determined with 1 or more affirmative items in the 7-Memory Questionnaire.

+Model adjusted for age, sex and years of education.

|

|

β |

CI 95% |

p value |

|

Loneliness |

-0.046 |

-0.080 , - 0.013 |

0.007 |

|

Social isolation |

-0.168 |

-0.089 , - 0.018 |

0.003 |

|

Subjective Memory Complaint |

0.812 |

-0.16 , - 0.11 |

<0.001 |

Table 6: Association of loneliness, social isolation and subjective memory complaint with daily cognitive function (E-Cog)++ Linear regression model.

Social isolation detected by EPII: physical distancing and quarantine.

Loneliness was determined with 1 or more affirmative items in the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale.

Subjective Memory Complaint was determined with 1 or more affirmative items in the 7-Memory Questionnaire.

+Model adjusted for age, sex and years of education. ECog was dependent variable using a suggested cutoff point of 1.31 (average).

Discussion/Conclusion

In this study, with data from a remote survey conducted in older adults living in the community, carried out during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico, we found a positive and statistically significant association with self-perception of loneliness and daily cognitive function. The frequency of loneliness in the participants is higher than that reported in the literature, being 84% compared to 30.9% and 43.1% reported by a cohort of older adults in California (San Francisco) and Canada, respectively, during the COVID-19 pandemic [23]. This feeling of loneliness appears to be even greater compared to the increase reported during confinement, for instance, in a cohort study of older adults in primary care in Hong Kong (n: 538, age: 70.6 + 6.1). Loneliness measured by the De Jong Gierveld scale during the COVID-19 pandemic increased from 1.6 to 2.9 positive items on average while the participants in our study had an average of 4.13 (1.1) positive items [24]. Consistent with previous studies [25], most of the participants with loneliness were women.

Older adults with the lowest report of loneliness were found in the lowest E-Cog scores, that is, those who referred loneliness during lockdown had a worse performance in the global E-Cog score. These findings coincide with those reported by Kim et al., who points out that loneliness predicts worse performance in several cognitive domains such as immediate memory, visuospatial skills and processing speed [26]. In two previous studies, carried out as cohorts from China and Argentina using the E-Cog scale, the additional memory domains, such as language, divided attention and planning [27] were associated with a lesser impact on functionality compared to FAQ (Functional Assessment Questionary) without showing an association with hippocampal hypometabolism, and the ROI (Regions of Interest) of Alzheimer’s disease compared to the memory-related domain [12] which could suggest greater usefulness for the detection of amnestic cognitive profiles compared to other scales.

The mechanism that explains how loneliness impacts on cognitive functions remarks a strong relationship with chronic stress underlying prolonged periods of loneliness, increased glucocorticoid activation and hypercortisolism. These physiological alterations occur differently depending on the loneliness’ period length. Thus, transient loneliness can activate the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis to negatively regulate inflammatory responses while persistent loneliness is associated with increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as: tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), Interleukin 1-beta (IL-1β), Interleukin 6 (IL-6), among others (COX-2 and iNOS) [6,28]. This state of chronic inflammation decreases dopamine signaling, circadian rhythm and monoamine levels (serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine) which in turn synaptic plasticity and neuronal survival decrease. Consequently, neurodegeneration increases, perpetuating axis dysfunction HPA (hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal) and physiological reward mechanisms [29]. In cohort studies, loneliness was associated with poorer performance in different types of memory, with a faster decline in semantic memory compared to episodic memory [30].

Although we found a trend in the positive correlation between loneliness and isolation, the results were not statistically significant with the E-Cog performance. This could be due to the fact that some of the participants might have not felt socially isolated at the beginning of confinement since data were collected in the first wave of lockdown. These results suggest that the concepts of loneliness and social isolation affect cognition by different and, probably, independent mechanisms. Unlike what is reported in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging, social isolation is associated with decreased episodic memory and verbal fluency after a 4-year follow-up period [30]. On the other hand, a Spanish study in older adults showed that greater social isolation is associated with lower scores in neuropsychological assessment batteries, reflected in both the global cognitive score and worse performance in verbal fluency and forward digits [31]. In animal models, these findings have been related to alterations in the CA2 region of the hippocampus, [7,8] therefore, it is plausible to detect social isolation as an additional risk factor for cognitive impairment. In general, social interaction generates demands that protect and maintain cognition, leaving isolated people vulnerable to impaired cognition [26,32]. Thus, we propose that social isolation in the participants of our study comes from an emergent situation as part of the preventive measures of contagion.

Previous studies with older adults during confinement as a result of COVID-19 in China report that being a woman and living alone carries a greater risk of perceived isolation since they depend more on family members and friends for social support. This was reduced due to social distancing during COVID-19 [33]. However, this condition of physical distancing does not imply the deprivation of the feeling of accompaniment, protection or closeness to people in the form of an emotional connection as it occurs when experiencing loneliness. That is, the significant effects of loneliness, conceptualized as (self-perceived) social isolation, on general cognitive function can be found together but not always [26,32].

Limitations and Strengths

Our study has some limitations, the design of the study, derived from an online survey. We do not have information prior to COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in these older adults, so we cannot know if they had isolation before the starting point of the study. We recognize that the E-Cog results were not compared with informant scores since there are previous studies where people with mild cognitive impairment reported performing better (lower scores) compared to the informants’ report (family members, caregivers) [27]. On the other hand, although E-Cog has shown good test-retest reliability, even in the Spanish version, where both global and domain-specific scores have shown different trajectories in participants with cognitive impairment, dementia and cognitive health [13,19,27] so, based on suggested cut-off point derivated from cross-sectional studies, [16] this sample had similar characteristics in unimpaired cognition and probably cognitive impaired. Among the strengths of the study, we were able to describe the health characteristics of a sample of Mexican older adults from the community during the first wave of the SARS-CoV2 pandemic. As far as we know, this is the first study conducted on Mexican older adults with daily cognitive function. Although loneliness and social isolation are usually empirically associated, they should be approached as distinct and independent phenomena.

Conclusion

In our study, we found that OA with loneliness have impairment in daily cognitive function which strongly suggests the need to increase vigilance of those identified with loneliness resulting from the deleterious effect on cognition, regardless of their isolation condition, in which case, differences are recognized between the natures of both. The SARS-CoV2 pandemic brought multiple challenges but also valuable lessons for clinicians. Regarding cognition, it was possible to recognize a latent but forgotten risk factor: loneliness. A frequent condition in older adults prior to the contingency, and that provides greater vulnerability, especially in those who already had cognitive impairment. A better understanding of this phenomenon will allow the development and adaptation of evidence-based interventions to address and prevent its impact on cognitive decline.

Acknowledgement

Statement of ethics/Institutional review board (IRB)

All participants gave their consent online to be included. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Research Committee of the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition Salvador Zubirán with the registration ID: GER-3410-20-21-1.

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Secretaria de Salud (2020) Institucion nacional de salud publica, IMSS, INEGI, CONAPO ROP de la salud. Boletín E Boletín estadístico: 1-27.

- Sepúlveda-Loyola W, Rodríguez-Sánchez I, Pérez-Rodríguez P, Ganz F, Torralba R, et al. (2020) Impact of Social Isolation Due to COVID-19 on Health in Older People: Mental and Physical Effects and Recommendations. J Nutr Heal Aging 24: 938-947.

- Freedman A, Nicolle J (2020) Social isolation and loneliness: the new geriatric giants: Approach for primary care. Can Fam Physician 66: 176-182.

- Luanaigh CO, Lawlor BA (2008) Loneliness and the health of older people. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 23: 1213-1221.

- Kotwal AA, Holt-Lunstad J, Newmark RL, Cenzer I, Smith AK, et al. (2021) Social Isolation and Loneliness Among San Francisco Bay Area Older Adults During the COVID-19 Shelter-in-Place Orders. J Am Geriatr Soc 69: 20-29.

- Akhter-Khan SC, Tao Q, Ang TFA, Itchapurapu IS, Alosco ML, et al. (2021) Associations of loneliness with risk of Alzheimer’s disease dementia in the Framingham Heart Study. Alzheimers Dement 17: 1619-1627.

- Mumtaz F, Khan MI, Zubair M, Dehpour AR (2018) Neurobiology and consequences of social isolation stress in animal model-A comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother 105: 1205-1222.

- Leser N, Wagner S (2015) The effects of acute social isolation on long-term social recognition memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem 124: 97-103.

- Manca R, De Marco M, Venneri A (2020) The Impact of COVID-19 Infection and Enforced Prolonged Social Isolation on Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Older Adults With and Without Dementia: A Review. Front Psychiatry 11: 585540.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, et al. (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42: 377-381.

- Farias ST, Mungas D, Harvey DJ, Simmons A, Reed BR, et al. (2011) The measurement of everyday cognition: Development and validation of a short form of the Everyday Cognition scales. Alzheimer’s Dement 7: 593-601.

- Hsu JL, Hsu WC, Chang CC, Lin KJ, Hsiao IT, et al. (2017) Everyday cognition scales are related to cognitive function in the early stage of probable Alzheimer’s disease and FDG-PET findings. Sci Rep 7: 1719.

- Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Cahn-Weiner D, Jagust W, et al. (2008) The Measurement of Everyday Cognition (ECog): Scale Development and Psychometric Properties. Neuropsychology 22: 531-544.

- Russo MJ, Cohen G, Chrem Mendez P, Campos J, Martín ME, et al. (2018) Utility of the Spanish version of the Everyday Cognition scale in the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia in an older cohort from the Argentina-ADNI. Aging Clin Exp Res 30: 1167-1176.

- Rueda AD, Lau KM, Saito N, Harvey D, Risacher SL, et al. (2015) Self-rated and informant-rated everyday function in comparison to objective markers of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 11: 1080-1089.

- van Harten AC, Mielke MM, Swenson-Dravis DM, Hagen CE, Edwards KK, et al. (2018) Subjective cognitive decline and risk of MCI: The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology 91: 300-312.

- De J, Gierveld J, Tilburg T Van (2006) A 6-Item Scale for Overall, Emotional, and Social Loneliness: Confirmatory Tests on Survey Data. Res Aging 8: 582-598.

- Grasso DJ, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Ford JD, Carter AS (2020) Epidemic-Pandemic Impacts Inventory (EPII).

- Filshtein T, Chan M, Mungas D, Whitmer R, Fletcher E, et al. (2020) Differential Item Functioning of the Everyday Cognition (ECog) Scales in Relation to Racial/Ethnic Groups. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 26: 515-526.

- Go RC, Duke LW, Harrell LE, Cody H, Bassett SS, et al. (1997) Development and validation of a structured telephone interview for dementia assessment (STIDA): The NIMH genetics initiative. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 10: 161-167.

- Brusselaers N, Lagergren J (2017) The Charlson Comorbidity Index in Registry-based Research. Methods Inf Med 56: 401-406.

- Charlson ME, Charlson RE, Peterson JC, Marinopoulos SS, Briggs WM, et al. (2008) The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J Clin Epidemiol 61: 1234-1240.

- Savage RD, Wu W, Li J, Lawson A, Bronskill SE, et al. (2021) Loneliness among older adults in the community during COVID-19: A cross-sectional survey in Canada. BMJ Open 11: 044517.

- Wong SYS, Zhang D, Sit RWS, Yip BHK, Chung RY, et al. (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on loneliness, mental health, and health service utilisation: A prospective cohort study of older adults with multimorbidity in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 70: 817-824.

- Zovetti N, Rossetti MG, Perlini C, Brambilla P, Bellani M (2021) Neuroimaging studies exploring the neural basis of social isolation. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 30: 29.

- Kim AJ, Beam CR, Greenberg NE, Burke SL (2020) Health Factors as Potential Mediators of the Longitudinal Effect of Loneliness on General Cognitive Ability. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 28: 1272-1283.

- Marshall GA, Zoller AS, Kelly KE, Amariglio RE, Locascio JJ, et al. (2014) Everyday Cognition Scale Items that Best Discriminate Between and Predict Progression From Clinically Normal to Mild Cognitive Impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res 11: 853-861.

- Bzdok D, Dunbar RIM (2020) The Neurobiology of Social Distance. Trends Cogn Sci 24: 717-733.

- Wilkialis L, Rodrigues N, Majeed A, Lee Y, Lipsitz O, et al. (2021) Loneliness-based impaired reward system pathway: Theoretical and clinical analysis and application. Psychiatry Res 298: 113800.

- Shankar A, Hamer M, McMunn A, Steptoe A (2013) Social isolation and loneliness: Relationships with cognitive function during 4 years of follow-up in the English longitudinal study of ageing. Psychosom Med 75: 161-170.

- Lara E, Caballero FF, Rico-Uribe LA, Olaya B, Haro JM, et al. (2019) Are loneliness and social isolation associated with cognitive decline? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 34: 1613-1622.

- Burns J, Movsisyan A, Jm S, Coenen M, Kmf E, et al. (2020) Travel-related control measures to contain the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10: CD013717.

- Brailean A, Steptoe A, Batty GD, Zaninotto P, Llewellyn DJ (2019) Are subjective memory complaints indicative of objective cognitive decline or depressive symptoms? Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Psychiatr Res 110: 143-151.

Supplement

Califique su capacidad para realizar ciertas tareas cotidianas AHORA, en comparación con sucapacidadpararealizardichastareashace 10 años. Enotraspalabras, tratederecordarcómosedesempeñabahace10 años eindiqueloscambiosquehanotado. Califiquelamagnituddelcambioenunaescaladecincopuntosquevade:

1)Sincambios,oenrealidadsedesempeñamejor que hace 10 años

2)Ocasionalmente hace la tarea peor, pero no todo el tiempo

3)Frecuentemente hace la tarea un poco peor que hace 10 años

4)Hace la tarea mucho peorque hace 10 años

5)No sé.

Marque el número que corresponda a surespuesta:

|

Encomparaciónconhace 10 años, hahabidoalgúncambioen... |

|||||

|

Memoria |

|||||

|

1.Recordaralgunosartículosparacomprarsin una lista |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

2.Recordarcosasqueocurrieronrecientemente(comosalidasrecientes,eventosenlas noticias). |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

3. Recordar conversaciones pocos días después. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

4.Recordardóndehapuestolosobjetos. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

5.Repetirhistoriasy/opreguntas. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

6.Recordarlafechaactualoeldíadelasemana. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

7.Recordarqueyalehadichoalgoaalguien. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

8. Recordar citas, reuniones ocompromisos. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

Lenguaje |

|||||

|

1.Olvidarlosnombresdelosobjetos. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

2.Darinstruccionesverbalesaotros. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

3.Encontrarlaspalabrascorrectasparausarenunaconversación. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

4.Expresarpensamientosenunaconversación. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

5.Seguirunahistoriaenunlibrooenlatelevisión. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

6.Entenderelsentidodeloqueotraspersonastratandedecir. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

7.Recordarelsignificadodepalabrascomunes. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

8. Describir un programa que ha vistoenla televisión. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

9. Entender instrucciones oindicacionesverbales. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

Habilidadesvisoespacialesyperceptivas |

|||||

|

1.Seguirunmapaparaencontrarunlugarnuevo. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

2. Leer un mapa y ayudar conindicacionescuandootrapersonaconduce. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

3. Encontrar su auto en unestacionamiento. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

4. Encontrar el camino de vuelta a unpuntodeencuentroenelcentrocomercialoenotrolugar. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

5.Orientarseenunvecindarioconocido. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

6.Orientarseenunatiendaconocida. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

7.Orientarseenunacasaquehavisitadomuchasveces. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

Funcionamientoejecutivo: Planificación |

|||||

|

1. Planificar la secuencia de paradasenunviajede compras. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

2. La capacidad de anticipar loscambios del clima yhacer planes enconsecuencia(esdecir, llevarunabrigooparaguas). |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

3.Desarrollaruncronogramaantesdeeventosprevistos. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

4. Pensar las cosas bien antes deactuar. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

5.Planificarconanticipación. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

Funcionamientoejecutivo: Organización |

|||||

|

1. Mantener organizado el espacio delavivienda y detrabajo. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

2.Llevarlascuentasdelachequerasinerrores. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

3.Mantenerlosregistrosfinancierosorganizados. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

4. Priorizar las tareas porimportancia. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

5.Mantenerlacorrespondenciaylosdocumentosorganizados. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

6. Usar una estrategia organizadapara manejar unhorario demedicamentosqueinvolucrevariosmedicamentos. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

Funcionamientoejecutivo: Atencióndividida |

|||||

|

1. La capacidad de hacer dos cosas alavez. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

2.Retomarunatareadespuésdeserinterrumpido. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

3.Lacapacidad deconcentrarseenuna tarea sin distraerse con cosasexternas del entorno. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

4.Cocinarotrabajaryconversaralmismotiempo. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

|

Total |

|

||||

Table 1: Everyday cognition scale.

Tomaszewski S, Reed B, et al. The Measurement of Everyday Cognition (ECog): Scale Development and Psychometric Properties. Neuropsychology 2008 July; 22(4): 531-544.doi:10.1037/0894-4105.22.4.531.

Por favor indique si los siguientes enunciados le aplican a su situación actual y responda como se siente actualmente en cada uno de los 6 enunciados. Las opciones para responder son: “si”, “más o menos”, “no”, “sin respuesta.”

|

Item |

Sí |

Más o menos |

No |

|

|

1 |

Siente una sensación de vacío a su alrededor. |

|

|

|

|

2 |

Hay suficientes personas a las que puede recurrir en caso de necesidad. |

|

|

|

|

3 |

Tiene mucha gente en la que confía completamente. |

|

|

|

|

4 |

Hay suficientes personas con las que tiene una amistad muy estrecha. |

|

|

|

|

5 |

Echa de menos tener gente a su alrededor. |

|

|

|

|

6 |

Se siente abandonado a menudo. |

|

|

|

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

Table 2: The De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale.

Gierveld, J. D. J., & Tilburg, T. V. (2006) A 6-Item Scale for Overall, Emotional, and Social Loneliness.

Research on Aging, 28(5), 582-598. doi:10.1177/0164027506289723

Nos gustaria entender cómo la pandemia del coronavirus (COVID-19) ha cambiado la vida de las personas. Para cada una de las frases que se presentan a continuación, por favor indique si la pandemia ha impactado su vida en forma personal o si ha impactado la vida de una persona en su hogar

Marque SI (YO) he sido impactado/a personalmente

Marque SI (PERSONA EN CASA) otra/s persona/s en casa han sido afectadas

Marque NO si usted o las personas en casa no han sido impactadas

Marque N/A si la frase no aplica a usted o a alguien en su hogar

***Si SI (YO) y SI (PERSONA EN CASA) aplica, marque ambas opciones

Desde que comenzó la pandemia del coronavirus, que ha cambiado para usted o su familia?

|

Item |

Si (YO) |

Si (Persona en la casa) |

No |

N/A |

|

|

A |

Trabajo y empleo: 1. Fue despedido del trabajo o tuvo que cerrar un negocio propio. 2. Ha tenido reducción de horas en su trabajo u obtuvo permiso laboral sin sueldo. 3. Despidió o dió permiso laboral sin sueldo a empleados o personas que supervisa. 4. Ha tenido que continuar trabajando aún en contacto cercano con personas que pueden estar infectadas (ej: clientes, pacientes, companeros de trabajo). 5. Ha dedicado mucho tiempo a desinfectar la casa dado al contacto cercano a personas que pueden estar infectadas en el trabajo 6. Ha aumentado la cantidad de trabajo o responsabilidades laborales. 7. Ha tenido dificultades para realizar el trabajo de forma adecuada, por tener que cuidar de personas en la casa. 8. Ha tenido dificultades para realizar la transición de trabajar desde la casa. 9. Ha tenido que proveer cuidado directo a personas con la enfermedad (ej.: doctor/a, enfermero/a, asistente en el cuidado del paciente, radiologo/a, otros). 10. Ha tenido que apoyar en el cuidado a personas con la enfermedad (ej.: personal de apoyo medico; guardian; administracion). 11. Ha brindado cuidado a personas que murieron como resultado de la enfermedad. |

|

|

|

|

|

B |

Eduación y entretenimie to: 1. Ha tenido un niño/a en casa que no ha podido ir a la escuela. 2. Usted es un adulto que no ha podido ir a la escuela o a sus entrenamientos por semanas o ha tenido que abandonar sus estudios. |

|

|

|

|

|

C |

Vida en la casa 1. Ha tenido dificultad para conseguir a alguien que le cuide los niños cuando lo ha necesitado. 2. Ha tenido dificultades cuando cuida a los niños en la casa. 3. Ha tenido mayor conflicto con niños o ha tenido que ser mas severo en la forma de disciplinarlos. 4. Ha tenido que hacerse cargo de tutorías o de enseñar al niño/niña o niños. 5. Parientes o amigos han tenido que mudarse a su casa. 6. Ha tenido que pasar mucho tiempo atendiendo las necesidades de un miembro de la familia. 7. Ha tenido que mudarse o relocalizarse. 8. Perdió su casa 9. Han aumentado las discusiones verbales o conflictos con su pareja o esposo (a). 10. Han aumentado los enfrentamientos físicos con su pareja o esposo (a). 11. Han aumentado las discusiones verbales o conflictos con otro(s) adulto(s) en la casa. 12. Han aumentado los enfrentamientos físicos con otro(s) adulto(s) en la casa. 13. Han aumentado los enfrentamientos físicos entre los niños en la casa. |

|

|

|

|

|

D |

Actividades sociales 1. No ha podido obtener suficiente comida o comida saludable. 2. No ha podido tener acceso a agua potable o limpia. 3. No ha podido pagar cuentas importantes como su renta o servicios (ej.: electricidad, etc.). 4. Ha tenido dificultad para llegar a lugares por la falta de acceso de transporte público o preocupación por su seguridad. 5. No ha podido obtener medicinas necesarias (prescripciones o de venta libre). |

|

|

|

|

|

E |

Economía 1. No ha podido obtener suficiente comida o comida saludable. 2. No ha podido tener acceso a agua potable o limpia. 3. No ha podido pagar cuentas importantes como su renta o servicios (ej.: electricidad, etc.). 4. Ha tenido dificultad para llegar a lugares por la falta de acceso de transporte público o preocupación por su seguridad. 5. No ha podido obtener medicinas necesarias (prescripciones o de venta libre). |

|

|

|

|

|

F |

Problemas físicos y de salud 1. Han aumentado los problemas de salud no relacionados con esta enfermedad. 2. Ha tenido menor actividad física o ha realizado menos ejercicio. 3. Ha comido demasiado o ha comido mayor cantidad de comidas menos saludables (ej.: comida chatarra). 4. Ha estado más tiempo sentado o en estado sedentario. 5. Ha tenido que cancelar un procedimiento médico importante (ej.: cirugía). 6. No ha tenido acceso a servicios médicos para una condición seria (ej.: diálisis, quimioterapia). 7. Ha recibido menos atención médica de lo habitual (ej.: citas de rutina preventiva). 8. Un miembro de la familia de edad avanzada o con discapacidad que no está en casa, no ha tenido la ayuda que necesita. |

|

|

|

|

|

G |

Salud mental y bienestar 1. Ha habido un aumento en problemas emocionales o problemas de comportamiento de los niños. 2. Han aumentado las dificultades para dormir en los niños o han presentado mayor cantidad de pesadillas. 3. Han aumentado los problemas de salud mental o síntomas mentales (estado de animo, ansiedad, estrés). 4. Han aumentado los problemas para dormir o ha tenido mala calidad de sueño. 5. Ha aumentado el uso de alcohol o sustancias. 6. No ha tenido acceso a tratamiento de salud mental o terapia. 7. No ha estado satisfecho(a) con los cambios en el tratamiento de salud mental o terapia. 8. Ha pasado mas tiempo enfrente de pantallas o equipos electrónicos (ej.: viendo el teléfono, jugando videojuegos, mirando televisión). |

|

|

|

|

|

H |

Distancia física y Cuarentena 1. Estuvo en aislamiento o cuarentena por la posibilidad de haber sido expuesto a la enfermedad. 2. Estuvo en aislamiento o cuarentena por síntomas de esta enfermedad. 3. Estuvo en aislamiento por tener condiciones de salud que incrementan el riesgo de infección o enfermedad. 4. Tuvo restricción en la cercanía física con su niño/niña o un ser querido por preocupación de contagio de la enfermedad. 5. Tuvo que mudarse o hacer arreglos de vivienda lejos de la familia por tener un trabajo de alto riesgo (ej.: empleado de la salud, emergencias). 6. Un familiar cercano que no vive en la casa estuvo en cuarentena. 7. Un familiar no pudo regresar a la casa por cuarentena o restricción por viaje. 8. Todos en la casa estuvieron en cuarentena por una semana o más. |

|

|

|

|

|

I |

Historial de infección: 1. Actualmente presenta síntomas de esta enfermedad, pero no le han hecho la prueba. 2. Le realizaron la prueba y actualmente esta padeciendo la enfermedad. 3. Tuvo síntomas de esta enfermedad, pero no ha tenido la prueba. 4. La prueba salió positiva para la enfermedad, pero ya no la padece. 5. Recibió tratamiento médico por padecer síntomas severos de la enfermedad. 6. Estuvo hospitalizado por la enfermedad. 7. Falleció alguien por esta enfermedad mientras estaba en nuestra casa. 8. Falleció un amigo/a o familiar por esta enfermedad. |

|

|

|

|

|

J |

Cambios positivos: 1. Ha tenido más tiempo de calidad en persona o en la distancia con familiares y amistades (ej.: por teléfono, correo electrónico, medios sociales). 2. Ha tenido más tiempo de calidad con su pareja o esposo/a. 3. Ha tenido más tiempo de calidad con los niños. 4. Han mejorado sus relaciones con familiares o amistades. 5. Ha tenido nuevas conexiones con personas que dan apoyo. 6. Ha aumentado la actividad física o el ejercicio. 7. Ha tenido más tiempo en la naturaleza o pasándola afuera. 8. Ha tenido más tiempo para realizar actividades placenteras (ej.: leyendo libros, armando rompecabezas) 9. Ha desarrollado nuevos pasatiempos o actividades. 10. Ha sentido más aprecio por cosas que usualmente no les damos importancia. 11. Ha prestado más atencion a la salud personal. 12. Ha prestado más atención para prevenir lesiones físicas. 13. Ha comido más alimentos saludables. 14. Ha disminuido el uso del alcohol o sustancias. 15. Ha pasado menos tiempo mirando pantallas o aparatos electrónicos fuera de las horas de trabajo (ej.: mirando el teléfono, jugando videojuegos, mirando televisión). 16. Ha donado su tiempo para ayudar a personas más necesitadas. 17. Ha donado su tiempo o productos a causas relacionadas con esta enfermedad (ej.: mascara/mascarilla, sangre, trabajo voluntario). 18. Ha encontrado un mayor significado en el trabajo o empleo o en la escuela. 19. Ha sido más eficaz o productivo en el trabajo o empleo, o en la escuela. |

|

|

|

|

Table 3: The Epidemic-Pandemic Impacts Inventory (EPII).

Grasso, D.J., Briggs-Gowan, M.J., Ford, J.D., & Carter, A.S. (2020) The Epidemic - Pandemic Impacts Inventory (EPII), Spanish Translation.

|

Item |

Si |

No |

|

|

1 |

¿Recientemente ha experimentado algún cambio en su capacidad para recordar cosas? |

|

|

|

2 |

¿Tiene más dificultad de lo normal para recordar una lista corta de artículos, como la lista de compras? |

|

|

|

3 |

¿Tiene dificultad para recordar cosas de un segundo a otro? |

|

|

|

4 |

¿Se le dificulta más de lo normal recordar eventos recientes? |

|

|

|

5 |

¿Tiene alguna dificultad para comprender o seguir instrucciones orales? |

|

|

|

6 |

¿Se le dificulta más de lo normal seguir una conversación grupal o una trama de un programa de televisión debido a su memoria? |

|

|

|

7 |

¿Tiene problemas para orientarse en calles familiares? |

|

|

|

|

Total |

|

|

Table: 4: The 7-Memory questionnaire.

Go, R. C. P., Duke, L. W., Harrell, Et al. (1997) Development and validation of a structured telephone interview for dementia assessment (STIDA): The NIMH genetics initiative. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 10(4), 161-167. https://doi.org/10.1177/089198879701000407

Citation: Durón-Reyes D, Mimenza-Alvarado A, Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez L, Suing-Ortega MJ, Avila-Funes JA, et al. (2022) Association of Loneliness, Social Isolation and Daily Cognitive Function in Mexican Older Adults Living in Community during the First Wave of COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown. J Gerontol Geriatr Med 8: 121.

Copyright: © 2022 Dafne Estefania Duron-Reyes, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.