Attitudes, Perceptions, Knowledge and Communication Interventions for Alcohol Exposed Pregnancies in Africa: A Scoping Review

*Corresponding Author(s):

Apophia AgiresaasiSchool Of Public Health, Makerere University, Uganda

Tel:+256 776626187,

Email:agiresaasi@gmail.com

Abstract

Background

Many women aged 15-49 continue to consume alcohol despite clinical recommendations and public health awareness campaigns about its dangers. A number of studies have documented women’s knowledge, attitudes, towards drinking during pregnancy and interventions that work. This review examined research on attitudes/ perceptions, knowledge and communication interventions addressing maternal alcohol use in Africa.

Objective

The primary objective was to review literature and research findings on attitudes and knowledge of women on alcohol use during pregnancy in Africa. A secondary objective was to investigate communication interventions implemented to address maternal alcohol use.

Methods

Potentially relevant articles were identified through a standardized systematic literature review. Published literature was identified through searches of various academic data-bases.

Results

Relevant articles were identified. Most of them were published between2010to 2016. Most women appreciate that drinking during pregnancy reduces their chances of having a healthy baby especially high levels of drinking although some regarded it as beneficial. Adequate knowledge on particular effects of drinking during pregnancy ranged from 7.5% to 35.6%.Only one study assessed communication interventions that work in Africa.

Conclusions

Information available reveals that there are low levels of adequate knowledge on specific dangers of drinking during pregnancy among women. The subject of effectiveness of communication interventions for alcohol exposed pregnancies has been grossly understudied.

Paper

Background

Alcohol consumption during pregnancy can result into a set of conditions collectively known as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD).Alcohol drinking(any amount) during pregnancy in Africa has been documented in a number of countries and ranges from 2.6% in Ogun state in Nigeria to 59.28% in South south Nigeria(Duru et al,2003; [1,2] Fawole, Hunyinbo and Fawole,2003; Olagbuji,Ezeanochi,Ande and Ekaete ,2008 [3] Fawole, [4,5] Makyoto, Omolo, Kamweya, Harder and Mutai, 2013). However the discussion on effect of low levels of alcohol use on pregnancy and child outcomes is inconclusive. But no amount of alcohol during pregnancy has been proven to be safe [6]. There is no quantity or type of alcohol considered safe in pregnancy. However, the effects on the fetus are higher with frequent, heavier or binge drinking (Maier, 2001; Stratton, 1996).

In Africa, binge drinking during pregnancy was reported by a number of studies and ranged from 3.8% to 26% [7] (Croxford and Viljoen,1999;Ordionoba and Brisibe, 2011 [8]. Heavy maternal alcohol use has been investigated by some scholars and ranged from 1.3% in Bosomtwe district in Ghana to 6.3% in Western Uganda [9-11].

According to a World Health Organization [12] report of 2014, Sub Saharan Africa (SSA) is among the highest per capita rates of alcohol consumption in the world.There is likely to be a high burden of FASD in Africa given the relatively high prevalence of maternal alcohol consumption. This is because countries with relatively lower prevalence and less risky drinking patterns such as USA and Canada have reported a high burden of FASD.

Knowledge and perceptions of women are an important predictor of maternal alcohol use [13, 14]. A number of scholars have studied knowledge, attitudes/perceptions of pregnant women and health workers regarding alcohol use during pregnancy in Africa.The success of alcohol prevention interventions depends on social factors such as knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of maternal drinking. It is essential to understand how women, their families and communities understand and perceive drinking during pregnancy to come up with interventions that adequately address both individual and community level perceptions. The review also describes sources of information on drinking during pregnancy and communication interventions that have promoted awareness on dangers of maternal drinking in Africa.

Thus, a systematic review was conducted to identify, assess, and analyze the continental evidence on the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of alcohol use during pregnancy with a view to providing recommendations for scale up of alcohol exposed pregnancy interventions.

Methods

Research Question, Team and Protocol

The systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta - data Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [15]. The systematic review question was “What are the perceptions/attitudes and or knowledge of women,healthworkers, and communities about drinking during pregnancy in Africa and what are the potential communication strategies that have been deployed?” The first author searched for articles with help of an experienced librarian.

A pre-specified systematic review protocol was developed. This included the research question, definitions, and inclusion criteria for relevance screening and data extraction forms. The SR protocol and citation list of relevant articles is available on request.

Search Strategy and eligibility Criteria

A primary research was conducted to identify all related primary research inEnglish from all relevant databases and journal collections includinggoogle scholar,Sage Online Journals, Taylor and Francis Online, Wiley Online Library, Project Muse JSTOR (Journal Storage)by using the text words such as( “attitudes towards drinking during pregnancy” OR “perceptions about alcohol use during pregnancy” ) AND (“knowledge about drinking during pregnancy” OR “knowledge about alcohol use during pregnancy in Africa”) AND (“communication interventions for alcohol exposed pregnancies” OR “Africa”). We also manually searched the google search engine by interchanging the above text words with each other. Finally we used the reference citations in some articles for a further search. The initial search was conducted on 9th July 2017. A follow up search was conducted in 12th April 2018.

Relevance Confirmation and data extraction

At first all article references including title, abstract and key words that were deemed relevant to the topic were read, retrieved and stored using EndNote software. Their details were sub-grouped into title, year, Country, variables, design, database and findings. Afterwards, the full text of each article was electronically downloaded.

The inclusion criteria took into consideration the following: articles focusing on knowledge, perceptions attitudes towards alcohol use during pregnancy, interventions for alcohol exposed pregnancies, a study denoting Africa (directly and indirectly), original articles with a study design published in English. The exclusion criteria excluded the following: studies not focusing on either knowledge, attitudes/perceptions about alcohol use during pregnancy, topics not focusing on Africa, articles not published in English. Case reports and case series, conference proceedings, letters and commentaries were also excluded.

Review management and data analysis

Data extraction was conducted using the web-based systematic review software DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada). The data was then exported to Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation 2010) for descriptive analysis. Results with reference to “n” refer to the total number of samples, subjects, or participants for the presented outcome.

Based on the assumption that the prevalence estimates would have some heterogeneity between study populations, a random effects meta-analysis was conducted using the DerSimonian and Laird method. In some cases, more than one observation per study was included in the meta-analysis. We did not account for the potential similarity of these results as they were all independent observations on different sampling frames. We evaluated how much heterogeneity between studies was not explained by random error using the value I2. High heterogeneity, I2 > 60%, was expected, and our goal was to investigate whether there were study level variables that explained the heterogeneity and to provide a graphic of the studies for the reader. We caution readers not to use the summary estimates as an estimate of the average outcome across studies given that estimates were obtained from very different populations and no study level variables explained all the heterogeneity between studies. In the forest plots, p = 0.00 is actually p < 0.01. This is an output of STATA13 (StatCorp 2015) and is not open for the user to alter or redefine. Qualitative research studies were synthesized using a narrative review approach. This included two reviewers independently reviewing the results of each study and descriptively summarizing the key results as reported by the study authors. Summaries from both reviewers were discussed and consolidated to arrive at the final narrative description.

Description of Studies Included in the Review

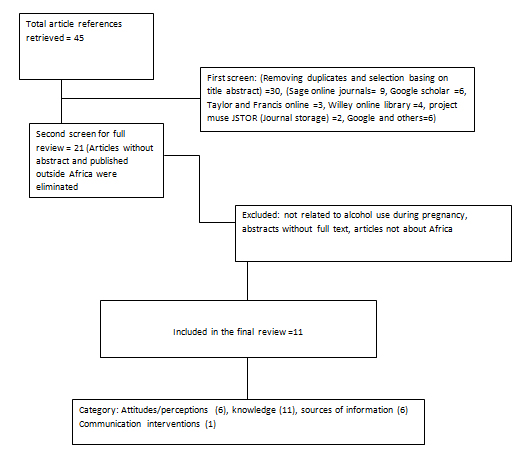

There were 45 citations initially screened for relevance, out of these 30 studies were considered for inclusion in this review. Only 18 articles of these were categorized to address perceptions, attitudes, knowledge about drinking during pregnancy and communication interventions. 7 Articles were regarded irrelevant in the relevance confirmation phase. Only 11 studies were included in this systematic review as seen in figure 1.

Almost all studies included in this review were published between 2010 and 2016(n=10) Only one study was published in 1999.Most of the studies were conducted in South Africa (n=5) followed by Ghana (n=2) and Nigeria (n=2) and Uganda (n=1) and Tanzania (n=1) as shown in Table 1. The most commonly used study design was cross - sectional (n=7) followed by Prospective descriptive (n=2), quasi experimental (n=1) and Qualitative (n=1) the main population studied was women (n=11), followed by healthcare professionals (n=1).Only a few studies were informed by theories of behavior change (n=2).

Figure 1: A PRISMA flow chart showing steps followed in retrieving and screening articles for review.

Figure 1: A PRISMA flow chart showing steps followed in retrieving and screening articles for review.

|

Continent |

Country |

Count/Percentage |

|

Africa |

Uganda |

1(9%) |

|

|

Tanzania |

1(9%) |

|

|

Ghana |

2(18%) |

|

|

Nigeria |

2(18%) |

|

|

South Africa |

5(45%) |

|

|

||

|

Study Design |

Cross sectional |

6(54%) |

|

|

Quasi Experimental |

1(9%) |

|

|

Longitudinal |

1(9%) |

|

|

Qualitative |

1(9%) |

|

|

Prospective |

2(18%) |

|

|

||

|

Population |

Women |

11(88%) |

|

|

General Public |

0(0%) |

|

|

Health Professionals |

1(11%) |

|

|

||

|

Theory of Behavior Used |

Health Belief Model |

1(19%) |

|

|

Social Ecological Theory |

1(19%) |

|

|

No theory reported |

9(81%) |

Table 1: General Characteristics of theEleven Primary Studies included in this Review

|

Author(Year) |

Country(Location) |

Samplesize |

Study Popn |

Study Type |

Results |

|

Adeyiga et al (2014) |

Ghana |

394 |

Women attending Obs and Gyn |

Cross-sectional |

Majority had negative attitude towards maternal drinking. Seeing a pregnant women drink made them feel concerned (31.5%) or angry (24.1%). The intensity of feelings were high (4-5) for 61.9% of women. |

|

Namagembe et al (2010) |

Uganda |

610 |

Ante-natal care attendees in a Kampala national hospital |

Cross-sectional |

Drinking waragi, an alcoholic drink, was perceived to ‘relieve heartburn’ and ‘make baby lighter’ with regard to their preference for vaginal delivery. Some respondents said they ‘drank beer to make the baby big’ |

|

AdosiPoku et al (2012) |

Ghana |

397 |

Women seeking Reproductive Health Services |

Cross sectional |

7.6% said alcohol had beneficial effects during pregnancy but did not agree that alcohol could have harmful effects except when taken in large quantities. These respondents were of the view that alcohol acted as a relaxant to reduce stress, it ‘cleaned’ the baby in the womb or acted as an appetizer |

|

Watt et al (2016) |

South Africa |

No mention of exact number of participants |

Women aged 18 and above who are pregnant or within one year of postpartum |

Qualitative In-depth interviews |

Participants described knowing women who consumed large quantities of alcohol throughout their pregnancies, which may suggest that to them that drinking while pregnant is normative behavior. Some women even received explicit encouragement from friends/peers to continue drinking. This perception was common. |

|

Loius Gideon (2014) |

South Africa |

128 |

ANC attendees who participated in Healthy Mother Healthy baby(HMHB) program |

Prospective descriptive study design quantitative and use of existing records. |

The perception of personal risk and the perception of general risk were highly correlated (r(126) = .743, p < .001). Cronbach’s alpha was calculated separately for the items measuring the perception of personal risk which consisted of 10 items (α = .871) and for the perception of general risk which also consisted of 10 items (α = .841). |

|

Chanelle Roux(2013) |

South Africa |

211 |

ANC attendees |

Quantitative cross-sectional |

Overall 7.5% of participants said alcohol is acceptable after attaining some gestational period. Overall 18%participants mentioned that occasional drinking during pregnancy was acceptable

|

Table 2: Attitudes/Perceptions towards Maternal Alcohol Use

Attitudes toward Maternal Alcohol Use during Pregnancy

Attitudes towards maternal alcohol use were addressed by 6 studies. (Table 2) Studies included in this review reveal conflicting views on maternal alcohol consumption. Some women regarded alcohol use during pregnancy as beneficial. Drinking waragi, an alcoholic drink, was perceived to ‘relieve heartburn’ and ‘make baby lighter’ with regard to their preference for vaginal delivery others reportedly ‘drank beer to make the baby big’ [7]. In Ghana, some women reported that drinking during pregnancy reduces stress and ‘cleaned’ the baby in the womb or acted as an appetizer(AdosiPoku et al, 2012).

Some women regarded alcohol use during pregnancy as acceptable. In South Africa, women reported that they were encouraged by peers to drink even when pregnant and they knew many women who drank big quantities of alcohol when pregnant(Watt et al, 2016),in another study in South Africa a small fraction of women regarded occasional maternal drinking or drinking after attaining some gestational period as alright(Channelle, 2013).

Yet others found drinking during pregnancy detestable. Women revealed that seeing a pregnant woman drink made them feel concerned and or angry [16] .With regard to risk perception, personal risk and general risk were correlated(Loius, 2014).

|

Author(Year) |

Country(Location) |

Samplesize |

Study Population |

Study Type |

Results |

Sources of Information |

|

Adeyiga et al, (2014) |

Ghana |

394 |

Women attending Obs and Gyn |

Cross sectional |

38.6% of women felt baby born of drinking other different from non -drinking mother 38.8% were unsure 1.8% adequately described differences |

· Media 9.1% · Health-worker 7.9% · Family 4.8 · Peers/Neighbor 2.3% · Others 2.5% · Did not know 59.4% |

|

Namagembe et’ al, 2010 |

Uganda |

610 |

ANC attendees |

Cross sectional |

Most healthcare students were not concerned about maternal alcohol use during trimester two and three. There was lack of awareness of outcomes associated with varying levels of alcohol consumption. No alcohol during pregnancy is the safest and most prudent choice they said. |

· No mention of sources of information |

|

Ordinioha B. and Brisibe S. (2014) |

South south Nigeria |

221 |

ANC attendees at Portharcourt teaching hospital |

Cross sectional survey(Semi structured interviewer administered questionnaire) |

51.58 % of respondents knew of the harmful effects of alcohol |

· 62.29% were told by a health professional. · 7.8% from media · 18.4% internet · 11.45% spouse |

|

Watt et al(2016) |

South Africa |

No mention of exact no. of respondents |

Women aged 18 and above who are pregnant or within one year of postpartum |

Qualitative In-depth interviews |

-The majority of women had never heard of FASD -Only a few women in the sample could name specific effects of fetal alcohol exposure, such as having a “premature birth” or the child “not [being] fully developed” or “[being] slow at school” -Participants possessed limited, inaccurate knowledge of the effects of fetal alcohol exposure. (One woman reported that “alcohol is actually good for the pregnancy” and another stated that it was only certain types of alcohol (i.e., “strong liquor”) that had the potential for harm |

· No mention of sources of information |

|

AdosiPoku et al (2012) |

Ghana Bosomtwe |

397 |

Women seeking reproductive healthcare services |

Descriptive cross-sectional |

7.6% said alcohol had beneficial effects during pregnancy compared to 78.0% who said alcohol could be harmful. 57.4% of these 78.0% gave spontaneous wrong answers when asked to mention some detrimental effects of maternal alcohol use. When asked the effects of alcohol on the mother, 83.4% of the 78.0% gave at least one or more answers whilst 16.6% did not know at all. When asked the effects of alcohol on the foetus; 81.4% of the 78.0% gave at least one correct answer and 18.6% did not know.

|

· 54.9% of the respondents received info on the detrimental effects of alcohol in pregnancy · 33.5 % received it at Antenatal Clinics · 12.8% from Radio · 11.0% from Television · 0.9 % from Newspapers

|

|

Onwuka et al, 2016) |

Eastern Nigeria |

380 |

ANC Attendees |

Cross sectional study |

35.5% of respondents were aware that alcohol is harmful to the fetus, 64.5% were unaware. |

· 33.3% got it from print media · 30.4% got it from health professionals · 28.9% from electronic media including the Internet · 6.7% got from friends/colleagues |

|

LoiusGidionJacobus (2014) |

South Africa (Northern Cape)De Aar |

128 |

ANC Attendees |

Prospective descriptive study quantitative and use of existing records.

|

-86.7% agreed that no amount alcohol is safe during pregnancy -Mean score on the FASD knowledge questions was 8.75 (SD = 1.72). |

· No mention of sources of information |

|

Chershish et al, (2012) |

Northern Cape( De Aar) South Africa |

1500 |

Women in De Aar and Upington |

Quasi experimental |

92% of participants stated that one drink during pregnancy harms the fetus. |

· 60% reported receiving this information from a nurse.

· 39.5% of cases and controls recalled having received information about FASD on the radio or television.

|

|

Chanelle le Roux(2013) |

South Africa |

211

|

ANC Attendees

|

Quantitative cross-sectional -Two validated questionnaires used |

Overall, 54% of all participants were found to be aware that alcohol could be harmful during Pregnancy 19% of private and 3% of state participants had adequate knowledge on dangers of drinking during pregnancy 98% private and 77% of government participants said alcohol had no effect on baby.

|

· 78% private and 37% of state participants got information from Media · 68% of private and 25% of state participants got information from family and friends · 60% of state and 54% of private participants got information from Health Professionals · 6% of state participants and 0% of private participants got information from Studies

|

|

Croxford and Viljoen(1999) |

South Africa(Western Cape) |

636 |

ANC Attendees

|

Prospective cross sectional structured interview. |

59.7% of the women were aware that alcohol could be harmful to the fetus. Of these 88.1% of significant drinkers indicated awareness 35.6% of the significant drinkers had a degree of insight, ranging from minimal to excellent knowledge; of the potential teratogenic effects of alcohol. 22.8% women who abstained from alcohol/drank minimally indicated insight into dangers of maternal drinking |

· No mention of sources of information |

|

Mosha T. and Philemon N,(2010) |

Tanzania (Morogoro) |

157 |

ANC Attendees |

Longitudinal Survey |

42.7% of respondents were not aware that alcohol use during pregnancy has adverse effects on baby. 29.3% knew of the effects of alcohol on unborn baby. 28% had knowledge that alcohol use during pregnancy is dangerous but did not know what it caused. |

· No mention of sources of information |

Table 3: Knowledge on Drinking During Pregnancy

Knowledge of Dangers of Drinking During pregnancy

All the Eleven studies included in this review reported on knowledge of participants on dangers of drinking during pregnancy.Seven studies assessed general knowledge. (Table 3) Women reported that they were aware that alcohol use during pregnancy could potentially harm the mother or the foetus and this ranged from 35.5% in Eastern Nigeria to 92% in Northern Cape South Africa(Adeyiga et al, 2014;Adosi Poku et al,2012;Onwuka eta l,2016;Louis G. 2014 [17] Chanelle R.2013;[18]

Four studies documented lack of awareness. The levels of lack of knowledge that alcohol use during pregnancy can result into poor pregnancy and child outcomes were relatively high and worrying and ranged from 16.6% in Ghana to 64.5% in Eastern Nigeria(AdosiPoku et al, 2012; Adeyiga et al,2014 [19] and Onwuka et al,2016).Adequate knowledge on particular effects of drinking during pregnancy on either mother or baby was assessed by four studies and ranged from 7.5% to 35.6%(Chanelle R., 2013;Mosha T. and Philemon N. 2010;Adeyiga et al, 2014 and Croxford and viljoen,1999).

In a qualitative study conducted in South Africa, most women had not heard about FASD and felt on certain types of alcohol could cause harm. Most of these women also had very little knowledge on what dangers maternal drinking can cause.

Sources of information

Six studies reported on sources of information. Most women reported that they obtained information on dangers of alcohol use during pregnancy from health workers (Ordionoba B. and Brisibe S.2014;AdosiPoku et al, 2012;Chanelle R.,2013 and Chershish et al,2012).This was followed by mass-media such as radio, television and print media (Adeyiga et al,2014;Onwuka et al, 2016 and Chershish et al,2012). Other sources of information on alcohol use during pregnancy included family, friends/peers and the internet.

|

Author(Year) |

Country(Location) |

Sample-size |

Study Pop |

Results |

Method |

|

Chershish (2012) |

South Africa |

1500 |

Women |

Reported increase in levels of awareness about alcohol harm. With odds of correct knowledge 5.8-10.3 higher in phase three than one. 74% of women believed using posters to communicate information about drinking could modify women’s drinking |

Quasi experimental Highlighted FASD using local media and health promotion talks at health facilities to increase awareness of alcohol harm and altar social norms in the communities.

|

Table 4: Communication Interventions for Alcohol Exposed Pregnancies

Communication Intervention addressing Maternal Alcohol Consumption

In this review only one study addressed communication interventions for alcohol exposed pregnancies as see in Table 4. It assessed FASD levels and knowledge levels regarding maternal alcohol use. FASD levels decreased after the intervention and awareness about dangers of drinking during pregnancy also increased.

Discussion

Some interviewees regarded maternal alcohol use as beneficial according to some primary studies included in this review. This is not dissimilar to other studies conducted outside Africa. ANC attendees in Denmark considered alcohol intake during pregnancy acceptable [20]. A similar study in France found that while only 6% of pregnant women would not consider drinking even one drink per day, 60% considered two drinks per day reasonable [21]. Alcohol consumption during pregnancy has been percieved to ‘relieve stress’ as maternal anxiety has been associated with mental health problems (O'connor, Heron, Golding, Beveridge and Glover, 2002). In the United Kingdom, a study revealed public belief that light drinking in pregnancy could enhance a child’s intelligence and behavior (Kelly et al, 2009; Raymond, Beer, Glazebrook and Sayal, 2009).

Some studies in this review revealed that some women had no idea that drinking during pregnancy could harm mother or baby and the proportion ranged from 16.6% in Ghana to 64.5% in Eastern Nigeria. Findings are no different from a similar study by Peadon and others in which 7.3% of pregnant women did not agree that drinking alcohol during pregnancy could harm the unborn child [22].

A study in Northern Cape Province of South Africa, assessed the effectiveness of intervention strategies aimed at increasing awareness of the harms caused by alcohol consumption during pregnancy (Chershish et al, 2012). The study assessed prevalence rates of FASD and knowledge regarding alcohol consumption before and after universal interventions. According to this study, FASD rates decreased from 8.9% pre-intervention to 5.7% post-intervention, while maternal awareness of harmful alcohol effects increased. These results are consistent with results of other studies.Related communication campaigns in other countries have been reported to increase awareness of dangers of alcohol use during pregnancy [23] (Casiro, Stanwick, Pelech and Tailor, 1994). Some studies have suggested that multiple exposures to warning messages can result into higher awareness levels than single exposures [7] (Marin, 1997). Literature also shows that effective messages should balance between describing the “thret” and promoting coping mechanisms and the self- confidence of the targeted audience, so that they can undertake the health behavior being promoted [24-28] (Poole, 2011; Thurmeier, et al., 2011).

Most of what has been documented about knowledge, attitudes and perceptions about alcohol use during pregnancy is documented in only five countries in Africa i.e South Africa, Ghana, Uganda, Tanzania and Nigeria.

There is a paucity of qualitative studies that have investigated knowledge and attitudes about maternal alcohol use during pregnancy. There is thus, a need for greater understanding and consideration of varying cultural explanations, contexts and circumstances under which pregnant women find themselves that may influence their decisions to use or abuse alcohol.

Based on this review, this subject has been understudied. We attempted to identify and include all relevant research on this subject using the scoping and systematic review methodologies but possibly some studies in other languages other than English and other non -indexed studies were missed. Many of the identified studies investigated respondent’s attitudes, perceptions, knowledge on alcohol use during pregnancy. Only one study investigated effectiveness of a communication intervention.

The relationship between individual behavior and these variables studied(Knowledge and attitudes) can be explained by the various theories of behavior change such as the Theory of Planned behavior, the Health Belief theory and others yet only two studies in this review used (read reported)a theory to guide their data collection and analysis.

This review included both women and health care workers but most of the articles studied women seeking antenatal and other maternal healthcare services at health facilities (n=10). Thus it’s not possible to compare with different sub populations.Information on various sub populations might be useful in informing education prevention campaigns as both primary and secondary influencers such as spouses, mother in laws and community leaders may have a bearing as whether women choose to drink or not to drink during pregnancy.

It was difficult to identify the risk of bias for all studies included in this review as most (more so quantitative studies) did not report on potential confounders or on whether tools were reliably tested and validated.

The effectiveness of public health interventions that aim to increase awareness, increase risk perception and reduce alcohol consumption among pregnant women could not be assessed because of the paucity of studies. Only one study in this review assessed effect of a communication intervention on maternal alcohol use.

Conclusions and recommendations

Health workers are vital sources of information on alcohol use during pregnancy. Healthcare facilities should include alcohol teachings and screenings during antenatal care visits. There is need for more research on communication interventions that work to identify what categories of women should be targeted. There are alarmingly low levels of knowledge on specific dangers maternal alcohol use can do to the mother and baby. Education campaigns should specifically address dangers of drinking during pregnancy to increase women’s risk perceptions.

References

- Etukumana EA, Thacher TD, Sagay AS (2010) HIV risk factors among pregnant women in a rural Nigerian hospital West Indian Med J 59: 424–428.

- Ezugwu EC, Agu P, Ohayi SA, Okeke TC, Dim CC, Obi SN et al (2012) HIV sero-prevalence among pregnant women in a resource constrained setting, South East Nigeria. Niger JMed 21: 338–342.

- Ordinioha B ,Brisibe S, (2011) Alcohol consumption among pregnant women attending the ante-natal clinic of a tertiary hospital in South-South Nigeria Nigerian Journal of Clinical practice 18:13-17.

- Fawole AO, Hunyinbo KI, Fawole OI (2008) Prevalence of violence against pregnant women in Abeokuta, Nigeria Australian and NewZealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 48: 405–414.

- Yoon HJ, Bonsu G, Akoto-Ampaw A, Nkrumah-Mills G, Nimo JJ, Park JK ,Ki M et al(2012) Prevalence and risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus infection in pregnant women in Eastern Ghana Brazilian J Infect Dis 16: 217–218.

- Kinney J Loosening the Grip in a Hand Book of Alcohol Information Sixth Edition ed Boston McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, 2000: 84-6.

- Namagembe I, Jackson LW, Zullo MD,Frank SH,Byamugisha JK, Sethi A K et al (2010) Consumption of Alcoholic Beverages among Pregnant Urban Women Matern Child Health J 14:492-500.

- Williams AD,Nkombo Y, Nkodia G, Leonardson G,Burd L et al (2013) Prenatal alcohol exposure in the Republic of the Congo: prevalence and screening strategies,Birth Defects Res (Part A) ClinMolTeratol 97:489-96.

- Adusi-Poku Y, Edusei AK, Bonney AA,Tagbor H, Nakua E, Otupiri E, et al (2012) Pregnant Women and Alcohol Use in Bosomtwe District of the Ashanti Region-Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health; 16:55-60.

- Duru MU, Aluyi HS, Anukam KC (2009) Rapid screening for co-infection of HIV and HCV in pregnant women in Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci : 9: 137–142.

- English L,Mugyenyi GR ,Kiwanuka G,Ngonzi J,Grunau BE,MacLeod S,Koren G,Delano K, Kabakyenga J, Wiens M (2015) Prevalence of Ethanol Use Among Pregnant Women in Southwestern Uganda J ObstetGynaecol Can ;37:901–902.

- World Health Organisation (2014) Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health

- Egger G,Spark R,Lawson J (2004) Health promotion strategies and methods. Sydney, Australia McGraw-Hill Book Company.

- Meillier LK ,Lund AB, Kok G (1997) Cues to action in the process of changing lifestyle. Patient EducCouns 30:37-51.

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M et al (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement Syst Rev 2015 Jan 1:1

- Adeyiga G, Emilia A,Udofia EA, Yawson AE (2014) Factors Associated with Alcohol Consumption: a Survey of Women Childbearing at a National Referral Hospital in Accra Ghana African Journal of ReproductiveHealth; 18:152-165.

- Chersich MF, Urban M, Olivier L, Davies LA, Chetty C, Viljoen D et al ( 2012) Universal prevention is associated with lower prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in Northern Cape, South Africa: a multicentre before-after study. Journal ofAlcohol and Alcoholism(oxford) 47: 67-74.

- Croxford J ,Viljoen D (1999) Alcohol Consumption By Pregnant Women in the Western Cape Foundation for Alcohol Related Research (Foundation for Alcohol Related Research/Department of Human Genetics,University of Cape Town , 89:962-5.

- Mosha TCE, Philemon N (2010) Factors influencing pregnancy outcomes in MorogoroMunicipality Tanzania Tanzan J Health Res 12: 249–260.

- Kesmodel U (2001) Binge drinking in pregnancy: frequency and methodology. Am J Epidemiol 154:777–82.

- Lelong N, Kaminski M, Chwalow J, Bean K, Subtil D et al ( 1995) Attitudes and behavior of pregnant women and health professionals towards alcohol and tobacco consumption Patient EducCouns, 25: 39-49.

- Peadon E, Payne J,Henley N,Dantoine H, Bartu A,Oleary C,Bower C, Elliot JE et al (2010) Women’s Knowledge and Attitude Regarding alcohol Consumption in pregnancy A national survey.BMC Public Health 10:510.

- Burgoyne W, Willet B, Armstrong J, (2006). Reaching women of childbearing age with information about alcohol and pregnancy through a multi-level health communication Journal of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome International,19 September (4), e17

- Clarren S, Salmon A, Jonsson E (2011) Introduction to Prevention of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder FASD, Weinheim: Viley VCH-

- Hanlon C, Medhin G, Alem A, Tesfaye F, Lakew Z, Worku B, Dewey M, Araya M, Abdulahi A, Hughes M, Tomlinson M, Patel V, PrinceM et al (2009) Impact of antenatal common mental disorders upon perinatal outcomes in Ethiopia: the P-MaMiE population-based cohort study. Trop MedInt Heal 14: 156–166.

- Hanson DJ,Winberg A, Elliot A (2012) Development of a Media Campaign on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders for Northern Plains American Indian Communities Society for Public health Education 13:842-847.

- Mengel MB, Ulione M, Wedding D, Jones ET, Shurn D et al (2005) Increasing FASD knowledge by a targeted media campaign: outcome determined by message frequency.JFAS Int 3:13.

- O’Connor MJ, Tomlinson M, Leroux MI, Stewart J, Greco E et al (2011) Predictors of Alcohol Use Prior to Pregnancy Recognition among Township Women in Capetown, South Africa.SocSci Med 72:83-90.

Citation: Agiresaasi A, Nassanga G, Nazarius TM (2021) Attitudes, Perceptions, Knowledge and Communication Interventions for Alcohol Exposed Pregnancies in Africa: a Scoping Review. J Alcohol Drug Depend Subst Abus 9: 026.

Copyright: © 2021 Apophia Agiresaasi, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.