Benefits and Barriers to the Utilisation of Safe Male Circumcision Services by Young Men Aged 15-24 in Rhino Camp Refugees Settlement in Arua District- Uganda

*Corresponding Author(s):

Atuhaire SCavendish University, Kampala, Uganda

Tel:+256 774636127,

Email:satuhaire@cavendish.ac.ug

Abstract

Up to date, only about 25% of males in Uganda are circumcised, yet Safe Male Circumcision (SMC) reduces the risk of HIV transmission by 60%. HIV prevalence in Uganda among people aged 15 to 64 is 6.2%, and 4.7% among males. Information about SMC among refugees aged between 15 -24 is inadequate which instigated this study. Across-sectional survey that utilized a mixed methodology approach was conducted among 378 young men aged 15 to 24 who were selected randomly and purposively to engage in focus group discussions and a semi-structured questionnaire. Correlations and binary regression were used to analyze the variable of interest at 95% confidence levels of utilization of SMC, benefits, and barriers. The prevalence of SMC uptake was 42.1%) (159/378). Its’ perceived benefits included reduction of cervical cancer among spouses and reduction in sexually transmitted infections among men including genital warts and penile cancer. About 72.6% of the barriers to SMS uptake were attributed to the likelihood of developing meatitis, while 74.2% was due to pain and 27.9% was due to discomfort. Young men in Rhino Camp Refugees’ Settlement anticipate great benefits from SMC which are both spousal and self-targeting however; the barriers continue to halt them. Dissemination of information, sensitization, and demystification about the perceived barriers could increase uptake and eventually reduce HIV prevalence.

Keywords

Circumcision; Refugees; Refugees settlement camps; Safe male circumcision

Introduction

Globally, 38 million people are living with Human Immuno-deficiency Virus (HIV) and of these 36.2 million are adults [1]. Sub-Saharan Africa is the most affected as approximately two-thirds of the people living with HIV are from this region [2]. The East African region is one of the regions with a high prevalence of HIV with Uganda having an HIV prevalence of 6.2% among adults aged 15-64, and 4.7% among males [3]. Interventions to curb this prevalence have been devised by World Health Organisation (WHO) in collaboration with The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and other stakeholders. One of them is Safe Male Circumcision (SMC), also referred to as Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision (VMMC); “the surgical removal of the foreskin - the retractable fold of tissue that covers the head of the penis” [4]. This is because the underlying part of the foreskin is highly susceptible to infections including HIV. Commonly, the procedure is taken for either religious, social, cultural, or medical reasons [5], but it is a one-off intervention with the capacity to reduce the risk of HIV infection by 60%, yet very cost-effective [4].

SMC is one of the five pillars to enable the achievement of less than 500,000 new infections by 2020 in priority countries with high HIV prevalence and low rate of SMC [6]. The WHO/UNAIDS currently targets 90% of the males aged 10-29 in priority countries including Uganda to have Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision by 2021. Variations have been observed in the trends of SMC uptake between countries. For instance, over 70% of adult men in Tanzania are circumcised. In Zimbabwe, about a quarter of adult men is circumcised [4]. The same scenario is observed in Uganda where to date about 25% of males in Uganda are circumcised despite information about its acceptability and safety [7]. A decade ago, the Ministry of Health set a goal to have 4,200,000 men safely and medically circumcised by 2015, although the uptake has remained low to date [8].

Apart from reducing HIV transmission, SMC also reduces the likelihood of heterosexually acquired Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) such as genital herpes, ulceration, oncogenic high-risk human papillomavirus and Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) [9-11]. Others include; a need for improved hygiene, holistic support, improved sexual performance, satisfaction, pleasure and financial savings [10]. Besides, circumcision is also associated with masculinity, identity, spirituality and social cohesion among men. To many, it is associated with the initiation to manhood and acts as a symbol of transition from childhood to adulthood. This is in ethnic groups that view the foreskin as the feminine element hence its removal makes a man out of the child [11]. This belief is also common in Uganda among the Bamasaba and Sabiny in Eastern Uganda [12].

The barriers to SMC include; beliefs and individual opinions on the emotional or physical pain, others are not sure about how sexual encounters might be without the foreskin but believe that it could be unpleasant, they associated circumcision with shame and humiliation, and believe it is costly [10]. Financial issues were also widely discussed including reduced income and worry of how the family will survive recovery the period of recovery and the fear of pain [13]. In addition young men especially those in refugee camps may not easily access such services even when they have the interest to carry out the procedure [14].

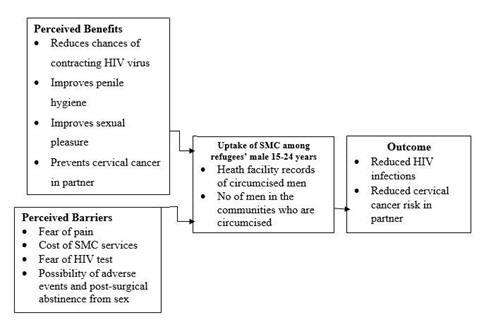

Rhino Camp Refugee Settlement is one of the refugees’ settlement areas in Uganda accommodating about 102,577 people [15]. Although health services are provided including SMC, the uptake is still inadequate for example only 44% of youth between the age group of 15 to 29 years in Nebbi, Packwach, and Arua were circumcised by the year 2019 as indicated on the West Nile website. Information about SMC among refugees aged between 15-24 is inadequate yet this age group is sexually active besides being a vulnerable population living in refugees’ settlement which instigated this study. The study was therefore conducted to determine the anticipated benefits and barriers to the uptake of SMC among men aged 15-24 in Rhino Camp Refugees Settlement, in Arua district in Uganda. The findings would also elicit scaling up of sexual and reproductive health services, and designing of appropriate interventions including dissemination of information, and sensitization on SMC to increase its’ coverage and ultimately reduce the prevalence of HIV in the country (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conceptual framework (adopted and modified from various literature including [9-11].

Figure 1: Conceptual framework (adopted and modified from various literature including [9-11].

Methods

A cross sectional survey was used in combination with mixed methods of data collection on the benefits and barriers associated with the utilization of safe medical circumcision services among young men aged 15-24 years in the Rhino Camp Refugee Settlement with some parts in Madi-Okollo district whereas others were from Terego district in West Nile sub-region in the Northern Region, West Nile Sub-Region. Rhino Camp Refugees’ Settlement lies about 63.4 kilometers (39.4mi) northeast of Arua District headquarters. The coordinates of Rhino Camp Refugees’ Settlement are 2.9694’N 31.3970’E (Latitude: 2.969399; Longitude: 31.397042). Rhino Camp is inhabited by Aringa and Rigbo. Moreover, the economic activities in Rhino Camp Refugee settlement are fishing, agriculture and cattle rearing. The target population of refugees was 6,824 young men aged 15-24 years in Rhino Camp Refugees Settlements (UNHCR report, March 2019). These were included based on their age (15-24 years) and being able to give informed consent to partake in the study.

Sample size

A simple random sampling method was used to select the respondents. A list of the target group was obtained from the leaders of the six zones in Rhino Camp Refugee Settlement as well as the Office of the Prime Minister. Their names were entered in a computer-assisted software; a Special Package for Social Scientists (SPSS). A simple random sampling command was run to arrive at a sample size of 378 that was earlier calculated using the Glenn D. Israel formula of 1992. The respondents were taken through a semi-structured questionnaire from their homes at the most appropriate time for the individual. Respondents for the Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were purposively selected, each FGD had between 6-12 members (Amin 2000) and lasted between 45 minutes to 1 hour.

To ensure validity, the researcher ensured that questions were relevant to ensure that the collected data gave meaningful and reliable results represented by variables in the study. The researcher made use of the test-retest method whereby 10 people were given questionnaires and after two weeks the same questionnaire was administered to the same set of people to check the consistency in the response and determine how reliable it is. Data were coded and entered into SPSS version 21 for analysis. Descriptive statistics summarized data on respondents' characteristics and were presented as narratives, graphs, charts and frequency distribution tables. Measures of central tendency and dispersions such as means, median and standard deviations were also presented in tabular form, charts, and graphs. At the bivariate level, the perceived benefits and barriers associated with SMC utilization were determined. The Chi-squared Fishers’ exact test was used for categorical variables. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05 to avoid dropping important variables that were associated with SMC uptake.

At multivariate analysis, all statistically significant variables at the bivariate level of analysis were subjected to binary logistic regression analysis. The model was used to determine the strength of association and the results were reported as crude odds ratio with corresponding 95% confidence intervals and p- values. Second, a multi-nominal logistic regression analysis was considered for all variables at the unadjusted analysis that were statistically significant to establish those that were independently associated with the outcome. This was expressed as adjusted odds ratios, with 95% CI and p-values. The three FGDs conducted in Arabic, Bari and English Languages, were audio-recorded and transcribed. A systematic structure that enabled prioritization and assessment of emergent codes was used as a method of qualitative analysis.

Results

In reference to table 1, the majority 155/378 (41.0%) of the participants were willing to undergo SMC to help them improve on their penile hygiene while 151/ 378 (39.9%) of the respondents accepted that there are benefits of SMC in HIV prevention and that if they are circumcised; it would lower their chances of getting HIV. However, 145/378 (38.4%) of the participants were not sure if SMC can prevent cervical cancer in their sexual partners while 136/378 (36.0%) of the respondents disagreed that SMC would improve sexual performance and pleasure.

|

Variable |

Category |

Frequency n=378 |

Percentage % |

|

I think there are benefits for SMC in HIV prevention. |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

26 28 30 143 151 |

6.9 7.4 7.9 37.8 39.9 |

|

If I get circumcised, it would lower my chances of getting the HIV |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

43 27 22 135 151 |

11.4 7.1 5.8 35.7 39.9 |

|

Undergoing SMC would help me improve on my penile hygiene |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

36 23 30 134 155 |

9.5 6.1 7.9 35.4 41.0 |

|

SMC can prevent cervical cancer in my partner |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

42 106 145 60 25 |

11.1 28.0 38.4 15.9 6.6 |

|

SMC will improve my sexual performance and pleasure. |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

117 136 52 39 34 |

31.0 36.0 13.8 10.3 9.0 |

Table 1: Perceived benefits and utilization of safe male circumcision services.

Source: Primary data

In reference to table 2, no association was found between the variables of interest with the uptake of Safe Male Circumcision except for the perception that it prevents cervical cancer among spouses with a Crude OR=0.314 at 95% CI .127-.779) at bivariate analysis.

|

Variable |

Category |

SMC uptake |

COR (95% CI) |

p-value |

|

|

Yes (%) |

Yes (%) |

||||

|

I think there are benefits for SMC in HIV prevention. |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

8 (5.0%) 14 (8.8%) 12 (7.5%) 57 (35.8%) 68 (42.8%) |

18 (8.2%) 14 (6.4%) 18 (8.2%) 86 (39.3%) 83 (37.9%) |

1.0 0.809 (0.509-1.286) 1.491 (0.608-3.659) 0.663 (0.294-1.494) 0.994 (0.445-2.220) |

0.370 0.383 0.321 0.989 |

|

If I get circumcised, it would lower my chances of getting the HIV |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

19 (11.9%) 14 (8.8%) 12 (7.5%) 51 (32.1%) 63 (39.6%) |

24 (11.0%) 13 (5.9%) 10 (4.6%) 84 (938.4%) 88 (40.2%) |

1.0 0.848 (0.527-1.364) 0.767 (0.383-1.537) 0.564 (0.246-1.295) 0.506 (0.204-1.255) |

0.497 0.454 0.177 0.142 |

|

Undergoing SMC would help me improve on my penile hygiene |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

18 (11.3%) 10 (6.3%) 8 (5.0%) 54 (34.0%) 69 (43.4%) |

18 (8.2%) 13 (5.9%) 22 (10.0%) 80 (36.5%) 86 (39.3%) |

1.0 0.841 (0.527-1.344) 0.675 (0.322-1.413) 0.877 (0.359-2.145) 1.856 (0.770-4.474) |

0.470 0.297 0.774 0.168 |

|

SMC can prevent cervical cancer in my partner |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

21 (13.2%) 38 (23.9%) 59 (37.1%) 25 (15.7%) 16 (10.1%) |

21 (9.6%) 68 (31.1%) 86 (39.3%) 35 (16.0%) 9 (4.1%) |

1.0 0.815 (0.486-1.366) 0.782 (0.409-1.497) 0.559 (0.271-1.152) 0.314 (0.127-0.779) |

0.437 0.458 0.115 0.012* |

|

SMC will improve my sexual performance and pleasure. |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

43 (27.0%) 60 (37.7%) 20 (12.6%) 20 (12.6%) 16 (10.1%) |

74 (33.8%) 76 (34.7%) 32 (14.6%) 19 (8.7%) 18 (8.2%) |

1.0 0.736 (0.444-1.221) 0.930 (0.474-1.823) 0.552 (0.266-1.148) 0.654 (0.302-1.414) |

.235 .832 .112 .280 |

Table 2: Perceived benefits associated with the utilization of safe male circumcision services at bivariate analysis.

Source: Primary data, *Significance

With reference to table 3, the majority 153/378 (40.5%) of the respondents feared having an HIV test which is required for them to undergo SMC while 144/378 (38.1%) feared the financial cost of undergoing SMC. As far as pain is concerned, 142/378 (37.6%) of the respondent reported that they feared pain while undergoing safe male circumcision. As regards the affordability of undergoing SMC at private health facilities, 138/378 (36.5%) of the participants accepted that they cannot afford SMC at most private health facilities. One in every three 33.9% of the respondents indicated that they feared serious side effects associated with SMC while 125/378 (33.1%) reported that they were uncomfortable waiting for six weeks to resume sexual activities after SMC. Three in every ten 30.4% of the respondents reported that it was time-consuming for them to go for SMC at the health facility.

|

Variable |

Category |

Frequency n=378 |

Percentage % |

|

I fear pain while undergoing safe male circumcision. |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

86 142 12 102 36 |

22.8 37.6 3.2 27.0 9.5 |

|

I feel it’s very costly to undergo SMC in-term of financing |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

69 144 37 86 42 |

18.3 38.1 9.8 22.8 11.1 |

|

To me undergoing SMC is very painful and uncomfortable |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

86 144 15 85 48 |

22.8 38.1 4.0 22.5 12.7 |

|

I fear to have to test for HIV which is required for me to undergo SMC, I have to test for HIV |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

57 98 18 153 52 |

15.1 25.9 4.8 40.5 13.8 |

|

Its time consuming for me to go for SMC at a health facility. |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

75 115 27 101 60 |

19.8 30.4 7.1 26.7 15.9 |

|

I cannot afford cost of doing SMC at most private health facilities |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

84 138 29 79 48 |

22.2 36.5 7.7 20.9 12.7 |

|

I fear the serious side effects that I can get if I undergo SMC |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

95 128 30 96 29 |

25.1 33.9 7.9 25.4 |

|

I cannot wait for six weeks to resume sexual activities after SMC |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

80 86 28 125 59 |

21.2 22.8 7.4 33.1 15.6 |

Table 3: Perceived barriers and uptake of safe male circumcision services.

Source: Primary data

As indicated in table 4, findings show a significant association between the utilization of safe male circumcision with pain and discomfort, fear of HIV test results as a requirement before undergoing SMC, time constraint, high costs involved mostly in private health facilities, and the fear of the likely side effects of SMC. Fear of risk of meatitis, SMC preventing cervical cancer in partners, undergoing SMC being painful and uncomfortable, being unable to afford the cost of doing SMC at most private health facilities were found to be significantly associated with utilization of SMC services at multivariate analysis (Table 5).

|

Variable |

Category |

SMC uptake |

COR (95% CI) |

p-value |

|

|

Yes (%) |

Yes (%) |

||||

|

I fear pain while undergoing safe male circumcision. |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

32 (20.1%) 629 (39.0%) 2 (1.3%) 45 (28.3%) 18 (11.3%) |

54 (24.7%) 80 (36.5%) 10 (4.6%) 57 (26.0%) 18 (8.2%) |

1.0 0.765 (0.442-1.324) 0.2.963 (0.610-14.384) 0.751 (0.418-1.349) 0.593 (0.270-1.301) |

0.338 0.178 0.338 0.192 |

|

I feel it’s very costly to undergo SMC in-term of financing |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

24 (15.1%) 60 (37.7%) 20 (12.6%) 35 (22.0%) 20 (12.6%) |

45 (20.5%) 84 (38.4%) 17 (7.8%) 51 (23.3%) 22 (10.0%) |

1.0 0.747 (0.411-1.355) 0.453 (0.201-1.024) 0.777 (0.403-1.498) 0.587 (0.268-1.283) |

0.337 0.057 0.451 0.182 |

|

To me undergoing SMC is very painful and uncomfortable |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

27 (17.0%) 72 (45.3%) 6 (3.8%) 30 (18.9%) 24 (15.1%) |

59 (26.9%) 72 (32.9%) 9 (4.1%) 55 (25.1%) 24 (11.0%) |

1.0 0.458 (0.261-0.802) 0.686 (0.222-2.123) 0.839 (0.444-1.586) 0.458 (0.221-0.946) |

0.006* 0.514 0.589 0.035* |

|

I fear to have to test for HIV which is required for me to undergo SMC, I have to test for HIV |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

14 (8.8%) 46 (28.9%) 8 (5.0%) 65 (40.9%) 26 (16.4%) |

43 (19.6%) 52 (23.7%) 10 (4.6%) 88 (40.2%) 26 (11.9%) |

1.0 0.368 (0.179-0.758) 0.407 (0.134-1.233) 0.441 (0.223-0.873) 0.326 (0.145-0.733) |

0.007* 0.112 0.019* 0.007* |

|

Its time consuming for me to go for SMC at a health facility. |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

20 (12.6%) 52 (32.7%) 11 (6.9%) 50 (31.4%) 26 (16.4%) |

55 (25.1%) 63 (28.8%) 16 (7.3%) 51 (23.3%) 34 (15.5%) |

1.0 0.441 (0.235-0.827) 0.529 (0.210-1.331) 0.371 (0.195-0.706) 0.476 (0.231-0.980) |

0.011* 0.176 0.003* 0.044* |

|

I cannot afford cost of doing SMC at most private health facilities |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

20 (12.6%) 61 (38.4%) 15 (9.4%) 35 (22.0%) 28 (17.6%) |

64 (29.2%) 77 (35.2%) 14 (6.4%) 44 (20.1%) 20 (9.1%) |

1.0 0.394 (0.216-0.722) 0.292 (0.120-0.706) 0.393 (0.201-0.768) 0.223 (0.104-0.478) |

0.003* 0.006* 0.006* 0.000* |

|

I fear the serious side effects that I can get if I undergo SMC |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

27 (17.0%) 66 (1.5%) 15 (9.4%) 42 (26.4%) 9 (5.7%) |

68 (31.1%) 62 (28.3%) 15 (6.8%) 54 (24.7%) 20 (9.1%) |

1.0 0.373 (0.212-0.656) 0.397 (0.171-0.923) 0.511 (0.280-0.931) 0.882 (0.357-2.179) |

0.001* 0.032* 0.028* 0.786 |

|

I cannot wait for six weeks to resume sexual activities after SMC |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

26 (16.4%) 40 (25.2%) 12 (7.5%) 55 (34.6%) 26 (16.4%) |

54 (24.7%) 46 (21.0%) 16 (7.3%) 70 (32.0%) 33 (15.1%) |

1.0 0.554 (0.295-1.041) 0.642 (0.266-1.552) 0.613 (0.341-1.101) 0.611 (0.305-1.225) |

0.066 0.325 0.102 0.165 |

Table 4: Perceived barriers associated with the utilization of safe male circumcision services at bivariate analysis.

Source: Primary data, *Significance

|

Variable |

Category |

Crude PR (95% CI) |

p-value |

Adjusted 0R (95% CI) |

p-value |

|

I fear increased risk of meatitis (inflammation of the glans penis) |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

1.0 0.503 (0.281-0.898) 0.542 (0.239-1.228) 0.588 (0.324-1.069) 0.542 (.258-1.139) |

0.020* 0.142 0.082 0.106 |

1.0 0.726 (0.338- 0.959) 0.636 (0.216- 1.872) 0.741 (0.340- 1.615) 0.932 (0.364- 2.388) |

0.012* 0.412 0.450 0.883 |

|

SMC can prevent cervical cancer in my partner |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

1.0 0.815 (0.486-1.366) 0.782 (0.409-1.497) 0.559 (0.271-1.152) 0.314 (0.127-0.779) |

0.437 0.458 0.115 0.012* |

1.0 1.547 (0.779- 3.073) 1.729 (0.742- 4.028) 1.346 (0.524- 3.458) 2.455 (1.278- 3.627) |

0.213 0.204 0.537 0.004* |

|

To me undergoing SMC is very painful and uncomfortable |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

1.0 0.458 (0.261-.802) 0.686 (0.222-2.123) 0.839 (0.444-1.586) 0.458 (0.221-0.946) |

0.006* 0.514 0.589 0.035* |

1.0 0.976 (.431- 2.213) 1.169 (0.289- 4.721) 2.649 (1.100- 6.379) 0.742 (0.279- 1.973) |

0.954 0.827 0.550 0.030* |

|

I cannot afford cost of doing SMC at most private health facilities |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree |

1.0 0.394 (0.216-0.722) 0.292 (0.120-0.706) 0.393 (0.201-0.768) 0.223 (0.104-0.478) |

0.003* 0.006* 0.006* 0.000* |

1.0 0.538 (0.240- 1.203) 0.248 (0.080- 0.765) 0.385 (0.156- 0.948) 0.167 (0.058- 0.478) |

0.131 0.015* 0.038* 0.001* |

Table 5: Perceived risk, severity, benefits, barriers and utilization of safe male circumcision services among young men aged 15-24 years at multivariate analysis.

Source: Primary data, *-significance

The perceived benefits and barriers of Safe Male Circumcision

Qualitatively, fear of pain regarding circumcision was the concern mentioned most often. Young men expressed concern over pain specifically during the SMC procedure but they also feared pain during recovery due to potentially poor suturing or a surgical mishap resulting in a deformity. Accordingly, FGD 1 stated,

- “I was afraid because those who had gone for the circumcision were saying that it was very painful when the foreskin is cut, during suturing, and then after that, you are unable to perform your normal duties as usual. Being a person with dependents, it was not appealing to me.” Respondents in FDG 1

However, concern about pain was not universal; those who were not circumcised at the time of their interviews said that they were not concerned about pain.

- “No, no, right now I am 23, and there is no pain I will feel when I become circumcised because I have endured painful things so there is none I will feel when I become circumcised.” Respondents in FDG 2

The circumcised participants had the following view;

- “The provider who performed the circumcision gave me some pain killers, and I used them as prescribed to me. The drugs helped me such that the pain was bearable…I did not have too much pain.” Respondent in FDG 2 aged 18

FGDs also explored several other potential barriers to VMMC, including the abstinence period, voluntary counseling and testing as part of VMMC services, female partners’ opinions of circumcision, sexual function after SMC, potential adverse events, cultural concerns, and access to and quality of VMMC services. Several men recommended talking with partners about the abstinence period. Concerns over culture, adverse events and sexual function were few. The study found that VCT and access and quality of services were not barriers to uptake of SMC services. The following statements supported this:

- The chances of being infected with HIV/AIDS are significantly reduced. So are the chances of being infected with other associated sexually transmitted infections. I have heard people saying that if you are circumcised, you are prevented from many diseases like HIV because of the dirt that is staying within the foreskin so by cutting it off the chances of being infected become low. Respondents in FDG 3

Men in FGDs voiced negative attitudes towards VMMC because they believed that the procedure involved tampering with the most essential organ in any man’s life. They said,

- “The head of the penis could be cut in the process of removing the foreskin. Will the healthcare providers be able to replace it? What I know is that healthcare providers would merely apologize, but that apology would not replace the damaged penis. It would be a permanent disability. The procedure is also tantamount to castration!” Respondents in FDG 3

Study participants also shunned male circumcision because they were skeptical about the possible side effects of the anesthetic injection administered during the execution of the surgical procedure. Men believed that the injection had adverse effects on male fecundity.

- “I heard from one of my friends that the injection administered to control pain (during circumcision) could cause male infertility after some years. So why would I go for such an operation when manhood in our culture is defined by a man’s ability to reproduce? A 20-year old respondent”. Respondents in FDG 1

Discussion

Perceived benefits associated with the utilization of SMC services among young refugee men aged 15-24 years. Findings indicate that participants are aware of the benefits of SMC. Like other studies, young men know that SMC is a means of HIV prevention and this has been the motive among those who have taken up the procedure [11]. However, a significant number of youths have fears which prevent them from taking up this procedure even when the services are available and are very much aware of the benefits [8]. This implies that communities need to be well informed through precise information regarding SMC to erase the fears and boost uptake. Men should be health educated on the possible risks that come with SMC since those who receive the service to enhance sexual power tend to get involved in risky sexual behaviors after the procedure, which can be addressed with clear information on the risks associated with SMC. This is important because male circumcision does not give 100 percent protection against HIV infection, hence they could be infected post circumcision and infect their sexual partners as well.

In addition, findings indicate that receiving SMC was linked to its preventive ability to cervical cancer. This is supported by findings by [8] that male circumcision reduces the risk of oncological Human Papillomavirus (HPV). Again, it is in agreement with [16] whose findings noted that the benefits of SMC are not exclusive to men but also women. Several studies indicate that women encourage their husbands to get circumcised mainly to improve their hygiene, to enhance sexual performance, reduce the risk of getting HIV and other STIs [16]. This same finding was affirmed by older adolescent boys in a study by [8] who’s motivation to circumcise rested on protection against HIV, STIs and improved hygiene.

SMC uptake is facilitated by four top factors; the belief that SMC reduces health risks, improvement of hygiene; social support to have SMC, and the belief that it enhances sexual performance and satisfaction [17]. In terms of SMC programming, these findings suggest that SMC benefits were not well understood by young men and this can explain the current low coverage among this sub-population. More targeted messaging is needed to increase awareness of SMC benefits among young men so that uptake increases. The studies discussed do not give the status of SMC in refugee camps.

Perceived barriers associated with the utilization of SMC services among young refugee men aged 15-24 years. This study’s findings also showed a statistically significant relationship between SMC uptake and the various perceived barriers such as the cost involved including but not limited to time away from work and complications that may arise. This is similar to a study by [17] in Uganda and [18] in Tanzania whose findings stated that informants were concerned about the cost involved in male circumcision and cleanliness of instruments used in medical and traditional male circumcision procedures. Most often centers that offer SMC for free receive more males seeking for the service; however, centers that give compensation in terms of transportation, time lost during surgery, and for each day spent at the research site or the facility, are overwhelmed by numbers [18]. Therefore, financial compensation is a motivator to seeking SMC which should be thought about and integrated into interventions geared towards HIV prevention. Based on several other studies on the subject, the cost-effectiveness of male circumcision is comparable to other HIV prevention strategies [11,17,18].

Study findings noted that fear of pain and discomfort strongly affected uptake of SMC. This is probably because men are not well informed about the procedures. These results are consistent with a study by [19] in Zimbabwe who found that the fear of pain during the procedure prevented a significant number of from seeking SMC. Similarly, other studies also cited the fear of anticipated pain in addition to over bleeding and HIV testing; a requirement before circumcision of which they would not be ready to receive its results [7,20]. Other factors include timing due to the various schedules including sporting activities and examinations [17]. Such fears could be cleared through sensitization, pre-circumcision counseling and peer mentoring. These studies were community-based, dealing with men of all age groups, hence were not specific to the adolescents and young adults who were the focus of this study moreover in refugee camps.

Conclusion

Young men in Rhino Camp Refugees’ Settlement anticipate great benefits from SMC which are both spousal and self-targeting. However, the barriers including fear of accidental amputation of the penis, meatitis, pain and costs continue to halt many of them from seeking SMC. Dissemination of information, sensitization, and elucidation about the benefit of SMC beyond those already perceived, as well as addressing the barriers could increase uptake of SMC and eventually reduce HIV prevalence.

References

- Kates J (2015) The Global HIV / AIDS Epidemic. Henry J Kaiser Fam Found: 1-4.

- WHO (2021) Global Health Observatory. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Ministry of Health (2019) Uganda Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (UPHIA) 2016-2017: Final Report, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda.

- WHO (2018) Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- WHO (2021) Sexual and reproductive health Male circumcision?: global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- No authors listed (1993) The Prevention Game. 259: 1537.

- Lubogo M, Anguzu R, Wanzira H, Shour AR, Mukose AD, et al. (2019) Utilization of safe male circumcision among adult men in a fishing community in rural Uganda. Afr Health Sci 19: 2645-2653.

- Nevin PE, Pfeiffer J, Kibira SP, Lubinga SJ, Mukose A (2015) Perceptions of HIV and Safe Male Circumcision in High HIV Prevalence Fishing Communities on Lake Victoria, Uganda. PLoS One 10: 0145543.

- Tobian AA, Quinn TC (2014) Prevention of syphilis: another positive benefit of male circumcision. Lancet Glob Health 2: 623-624.

- Gabriel GO (2020) Voluntary Male Circumcision and Risk for Human Immunodeficiency Virus in Homa Bay, Kenya. Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies.

- WHO (2007) Male circumcision Male circumcision: global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Sarvestani AS, Bufumbo L, Geiger JD, Sienko KH (2012) Traditional Male Circumcision in Uganda: A Qualitative Focus Group Discussion Analysis,. PLoS One 7: 45316.

- Evens E, Lanham M, Hart C, Loolpapit M, Oguma I (2014) Identifying and addressing barriers to uptake of voluntary medical male circumcision in Nyanza, Kenya among men 18-35: A qualitative study. PLoS One 9: 98221.

- Kwankye SO, Richter S, Okeke-Ihejirika P, Gomma H, Obegu P, et al. (2021) A review of the literature on sexual and reproductive health of African migrant and refugee children. Reprod Health 18: 81.

- UNHCR (2019) Government of Uganda office of the prime minister Uganda refugees & asylum seekers as of 31-october-2019 population summary by settlement / sex Uganda refugees & asylum seekers AS OF 31-October-2019 Population Summary by Country of Origin / Sex. UNHCR. Pg no: 1–8.

- Kibira SPS, Daniel M, Atuyambe LM, Makumbi FD, Sandøy IF (2017) Exploring drivers for safe male circumcision: Experiences with health education and understanding of partial HIV protection among newly circumcised men in Wakiso, Uganda. 12: 0175228.

- Ssekubugu R, Leontsini E, Wawer MJ, Serwadda D, Kigozi G, et al. (2013) Contextual barriers and motivators to adult male medical circumcision in Rakai, Uganda. Qual Health Res 23: 795-804.

- Tarimo EAM, Francis JM, Kakoko D, Munseri P, Bakari M, et al. (2012) The perceptions on male circumcision as a preventive measure against HIV infection and considerations in scaling up of the services: A qualitative study among police officers in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Public Health 12.

- Hatzold K, Mavhu W, Jasi P, Chatora K, Cowan FM, et al. (2014) Barriers and motivators to voluntary medical male circumcision uptake among different age groups of men in Zimbabwe: Results from a mixed methods study. PLoS One 9: 85051.

- George G, Strauss M, Chirawu P, Rhodes B, Frohlich J, et al. (2014) Barriers and facilitators to the uptake of voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) among adolescent boys in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res 13: 179-187.

Citation: David BM, Bandaru JM, Namajja KE, Atuhaire S (2022) Benefits and Barriers to the Utilisation of Safe Male Circumcision Services by Young Men Aged 15-24 in Rhino Camp Refugees Settlement in Arua District- Uganda. J Reprod Med Gynecol Obstet 7: 0100.

Copyright: © 2022 David BM, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.