Central diabetes insipidus (CDI) in very low birth weight neonate: case report

*Corresponding Author(s):

Allam FM AbuhamdaNeonatologist, NICU, Sultan Qaboos Hospital, Salalah, Dhofar, Oman

Tel:009894438489,

Email:allam570@yahoo.com

Abstract

Diabetes Insipidus (DI) is rare, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 25,000 cases; less than 10% of cases are hereditary. CDI accounts for over 90% of DI cases and can appear at any age, depending on the cause. There is no indication that hereditary CDI causes are frequent. Central diabetes insipidus (CDI) is uncommon in neonates, particularly in very low-birth-weight newborns, and the great majority of cases are caused by disorders such as ischemia damage or bleeding brain injury. CDI is caused by a deficiency of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) as a result of posterior pituitary and/or hypothalamus dysfunction. Our kid was delivered in Sultan Qaboos Hospital in Salalah at 28 weeks gestational age, with a very low birth weight of 1001 grams. She also suffered polyuria and hypernatremia. The baby was identified with central diabetes insipidus early on and was effectively treated with oral desmopressin.

Keywords

Central diabetes insipidus; Desmopressin; Sultan Qaboos Hospital;Salalah.

Introduction

Diabetes Insipidus (DI) is rare, with an estimated incidence of one in every 25,000 people; less than 10% of cases are hereditary. CDI accounts for over 90% of DI cases and can appear at any age, depending on the cause. There is little indication that hereditary CDI causes are widespread [1,2].

Central diabetes insipidus (CDI) is uncommon in neonates, particularly in very low-birth-weight infants, and the great majority of cases are caused by disorders such as ischemia damage or bleeding brain injury [3-7].

CDI is caused by a deficiency of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) as a result of posterior pituitary and/or hypothalamus dysfunction. CDI is an uncommon disease that causes increased urine production and hypernatremia. Infant water and electrolyte balance are affected by postnatal physiological adaptations, and proper treatment is crucial, especially for severely ill newborns. Dehydration with hypernatremia can occur in neonatal CDI cases, followed by insensible water loss, increased urine output, and a reduced capacity to release salt. Meticulous monitoring is essential to maintain hydration and electrolyte balance in newborn with CDI [8].

Background

When you take a care of a very preterm newborn with a very low birth weight, it is critical to maintain optimal hydration and electrolyte balance. The newborn's situation was complicated since she received appropriate hydration and salts but continued to have hypernatremia and polyuria. At the time, the case was diagnosed CDI and treated satisfactorily with oral desmopressin.

Case Presentation

The mother was G5P2, had gestational diabetes, had a preterm rupture of membranes for 7 days, and was given two doses of dexamethasone before birth. There was no family history of diabetes insipidus. The baby was a girl, born at 28 weeks gestational age through normal delivery and had a birthweight of 1001 grams on the 50th percentile, a circumference of the head was 25 cm on the 50th percentile, and a length was 33 cm above the 10th percentile. She lacked dysmorphic characteristics. The newborn was intubated in the birth room, then transferred to the NICU and connected to mechanical ventilation. The baby got two doses of surfactant and was kept on mechanical ventilation for 17 days before being extubated. The baby required IV inotropes throughout the first four days of life owing to hemodynamic instability, initial screening brain U/S revealed IVH grade 1, and all blood cultures were negative.

The newborn got enough fluid, received 100 ml/kg/day on the first day of birth and 190 ml/kg/day on the third day of life, baby had polyuria up to 10 ml/kg/h and serum sodium of 159 mEq/L (a typical range of 135 to 145).

The newborn had received 260 ml/kg/day IV fluid by the age of 10 days, serum sodium was 158 mEq/L, urine output was 9 ml/kg/hr, and urine specific gravity was 1.0050 (normal range, 1.002 to 1.030). At this age; The baby was diagnosed with diabetes insipidus. Staff attempted to manage the case by increasing fluid intake and compensating the polyuria but the hypernatremia was uncontrolled. At 25 days of age, the infant required 290 ml/kg/day of fluid, serum sodium was 151 mEq/L, and the baby had polyuria. The pediatric endocrinology team suggested the desmopressin to be given to the patient. At 28 days, the newborn took oral desmopressin 3 microgram bid, as well as the dose, was titrated based on the baby's overall condition; edema, urine output, and serum sodium in blood gases.

Oral desmopressin allowed blood sodium to be kept within a normal range with minimum variation and controlled polyuria, while providing the infant with an average fluid intake. Initially, the case required periodic blood gases, at least twice daily, to monitor serum sodium and regulate the dose of desmopressin by increasing or decreasing the dose.

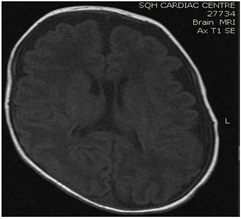

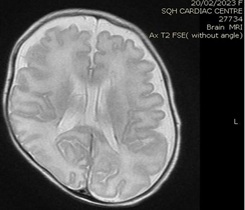

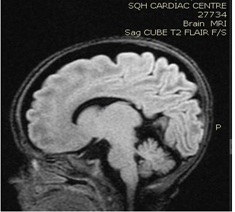

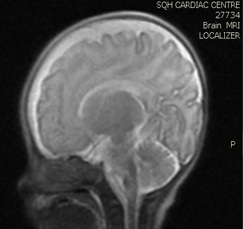

Brain MRI (images 1,2,3,4) at the age of 78 days; revealed that generalized relative simplified gyral pattern, generalized enlarged subarachnoid spaces as well as enlarged bilateral sylvian fissures, no diffusion restriction, no intracerebral hemorrhage, pituitary fossa appears normal in size, the posterior pituitary spot is not well defined.

Image 1

Image 1

Image 2

Image 2

Image 3

Image 3

Image 4

Image 4

The infant was released home at the age of 82 days; she was a feeder and grower, weight was 2110 grams, and head circumference was 33.5 cm, active, sucking well, and breathing effortlessly in room air. She was discharged on oral desmopressin 4 micrograms, and serum sodium was regulated with the same dose of desmopressin for several days before discharge.

The mother was taught how to care for her infant, how to evaluate hydration status, how to prepare, and how to administer desmopressin. The infant had been scheduled for appointments at the pediatric endocrinology clinic and the newborn clinic.

Discussion

Since her admittance, this infant has got standard care for a very preterm and very low birth weight neonate, and she has received average intravenous fluids since the first day. By day three, the baby had received 190 ml/kg/day IV fluid and had polyurea and serum sodium of 159 mEq/L. Since admission, the baby's neurological status has been stable; a simple screening of the brain revealed an IV grade 1, blood sugar and serum electrolytes were normal, the baby had normal saturation throughout the hospital stay and was not subjected to hypoxia; just for the first four days of her life, she required inotropes, due to hemodynamic instability which she then discontinued [9].

By 10 days, the infant was still on high IV fluid, had polyuria and hypernatremia, and her urine specific gravity was 1.0050, confirming the diagnosis of diabetes insipidus

The team managed the case by hydration and replacing urine output with IV fluid and feeding, but when we reached 290 ml/kg/day of IV fluid, the kid was still polyureic exhibiting hypernatremia. We began with desmopressin 3 mcg bid (tablet 200 mcg dissolved in 20 cm water) with strict monitoring of hydration status, urine output, and capillary blood gases for sodium before the dose since the infant was very low birth weight and was still fragile.

We were able to manage hypernatremia and polyuria with desmopressin and weaned the infant from a high fluid intake to a normal fluid intake per day [10-14]. The desmopressin response validated the diagnosis of central diabetes insipidus. Brain MRI data were also indicative of a central origin, particularly the posterior pituitary spot, which was not well delineated. In comparison with previously reported cases, we controlled the case with a little dosage of oral desmopressin, and oral desmopressin is more practical than intranasal dDAVP treatment [15,16], and oral desmopressin administration and modification of dosage is easier than nasal application [17].

Conclusion

A very premature infant, born at 28 weeks gestational age with a very birth weight of 1001 grams; she was diagnosed with central diabetes insipidus and treated safely and effectively with oral desmopressin. Desmopressin therapy necessitates frequent monitoring of hydration status, polyuria, serum sodium, and dosage calibration as needed.

Consent

Approval from hospital administration of Sultan Qaboos Hospital in Salalah (SQH) and consent was signed by the father for publication of brain MRI images and medical details of the case.

Conflict of Interest

Author declares no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to all medical staff; doctors and nurses, in the neonatal intensive care units, for their exceptional care of a so complicated cases.

References

- Abuhamda AF (2019) Neonatal Diabetes Insipidus in a Palestinian Newborn. Rossiyskiy Vestnik Perinatologii i Pediatric (Russian Bulletin of Perinatology and Pediatrics) 64: 101-103.

- Dabrowski E, Kadakia R, Zimmerman D (2016) Diabetes insipidus in infants and children. Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism 30: 317-328.

- Hussain A, Baier RJ, Mehrem AA, Soylu H, Fraser D, et al. (2020) Central Diabetes Insipidus in a Preterm Neonate Unresponsive to Intranasal Desmopressin. Neonatal Netw 39:339-346.

- Park Z, Yung (2020) Central diabetes insipidus in an extremely low-birth-weight preterm infant with suspected ectopic posterior lobe of the pituitary gland Neonatal Medicine 27: 31-36.

- Ferlin ML, Sales DS, Celini FP, Martinelli Junior CE (2014) Central diabetes insipidus: alert for dehydration in very low birth weight infants during the neonatal period. A case report. Sao Paulo Medical Journal 133: 60-63.

- Biset A, Claris O (2018) Idiopathic central diabetes insipidus in an extreme premature infant: a case report. Archives de Pédiatrie 25: 480-484.

- Hanta D, Törer B, Temiz F, K?l?çda? H, Gökçe M, et al. (2015) Idiopathic central diabetes insipidus presenting in a very low birth weight infant successfully managed with lyophilized sublingual desmopressin. The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics 57: 90.

- Ueda H, Numoto S, Kakita H, Takeshita S, Muto D, et al. (2016) Neonatal central diabetes insipidus caused by severe perinatal asphyxia. Pediatr Ther 6: 278.

- Saborio, Pablo, Gary A (2000) Diabetes insipidus. Pediatrics in Review 21: 122-129.

- Korkmaz HA, Demir K, K?l?ç FK, Terek D, Arslano?lu S, et al. (2014) Management of central diabetes insipidus with oral desmopressin lyophilisate in infants. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 27: 923-927.

- Atasay B, Berbero?lu M, Günlemez A, Evliyao?lu O, Adiyaman P, et al. (2004) Management of central diabetes insipidus with oral desmopressin in a premature neonate. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 17: 227-230.

- Stick SM, Betts PR (1987) Oral desmopressin in neonatal diabetes insipidus. Archives of disease in childhood 62: 1177-1178.

- Quetin F, Garnier H, Brauner R, Vodovar M, Magny JF et al. (2007) Persistent central diabetes insipidus in a very low birth weight infant. Archives de Pediatrie: Organe Officiel de la Societe Francaise de Pediatrie 14: 1321-1323.

- Sng A, Loke KY, Lim Y (2018) A case of neonatal central diabetes insipidus in a premature infant: Challenges in diagnosis and management. Case Rep J 2: 010.

- De Waele K, Cools M, De Guchtenaere A, de Walle JV, Raes A, et al. (2014) Desmopressin lyophilisate for the treatment of central diabetes insipidus: First experience in very young infants. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism 12: e16120.

- Alan S, K?l?ç A, Çak?r U, Y?ld?z D, Kahvecio?lu D, et al. (2012) 1321 The management of central diabetes insipidus in neonatal intensive care unit: Experience of eight cases. Archives of Disease in Childhood 97: A376-A377.

- Larijani B, Tabatabaei O, Taheri E (2005) Comparison of desmopressin (ddavp) tablet and intranasal spray in the treatment of central diabetes insipidus. DARU Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 13: 155-159.

Citation: Abuhamda AFM (2023) Central diabetes insipidus (CDI) in very low birth weight neonate: case report. J Neonatol Clin Pediatr 10: 107.

Copyright: © 2023 Allam FM Abuhamda, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.