Cholera in Marib Governorate, Yemen: Analysis of the Surveillance Data from W1, 2020- w45, 2023

*Corresponding Author(s):

Abdulla Salem Bin-GhouthFETP National Consultant, Professor Of Community Medicine, Hadhramout University, Yemen

Email:abinghouth2007@yahoo.com

Abstract

The Yemen cholera outbreak began in early October 2016, and by January 2017, the WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (WHO EMRO) considered the outbreak to be unusual in its rapid and wide geographical spread. In Marib Governorate at eastern Yemen, a cholera epidemic began to be recorded in April 2017 but due to political instability, the electronic disease early warning system (EDEWS) was discontinued during the period 2018-2019, and a new system of EDEWS was developed in the governorates under the control of the internationally recognized government (IRG), Marib at the east is one of these governorates where a lot of internally displaced people (IDPs) present and refuges.

Objective: the aim of this paper is to follow the trend of cholera during the period from January 1st 2002 to 2023 week 45.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of the available data from the EDEWS registry. The Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) of in Aden (Yemen) conducted analysis of the available data to describe the trends of the outbreak in Marib governorate. Data of the occurrence of suspected cholera from this analysis are presented in tables and graphs. The reporting period that included in the analysis is from the 1st epi week of 2020 to the 45th epi week of 2023 were obtained from EDEWS.

Results

A total of 4023 suspected Cholera cases were reported to EDEWS in Marib governorate during w1 of 2020 to W45/2023. Three cholera related deaths were reported giving the case fatality rate (CFR) of 0.075%.

In 2020 seven peaks were observed in the epi curve in Epi weeks 2,7,12,26.36.42 and 49. In 2021; four peaks were observed in Epi weeks 2, 7, 12 and 14. Although, only one peak was observed in 2022 in the Epi week 49, but three peaks were observed in the current year 2023 in the Epi Weeks No 2, 7 and 42.

The high proportion of the affected people were children between 1-?5 years (38%) followed by age group 5-?10 years (14%). Males had the highest recorded cases (56%) than female (44%).

Conclusion

Although Marib is occupied by a large number of IDPs, but the improvement in water supply, good surveillance and food security contributing in reduction of cholera cases in 2023. Further studies are needed to follow if there is changes in epidemiology of cholera from epidemic potential to endemicity.

Keywords

Cholera; Epidemic; Marib; Yemen

Introduction

Cholera is an acute, diarrheal illness caused by intestine infection with the toxigenic bacterium Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 or O139. [1] An estimated 1.3 to 4 million people around the world get cholera each year and 21,000 to 143,000 people die from it. People who get cholera often have mild symptoms or no symptoms, but cholera can be severe. Approximately 1 in 10 people who get sick with cholera will develop severe symptoms such as watery diarrhea, vomiting, and leg cramps. In these people, rapid loss of body fluids leads to dehydration and shock. Without treatment, death can occur within hours [2]. Cholera is a highly contagious disease. The environment plays an important role, the disease can spread rapidly in areas with inadequate sewage and water treatment [3] and it is transmitted primarily by ingestion of faecally-contaminated water by susceptible persons. Besides water, foods have also been recognized as an important vehicle for transmission of cholera. Foods are likely to be faecally contaminated during preparation, particularly by infected food handlers in an unhygienic environment [4]. Also, Cholera is more common in regions with poor access to clean water and sanitation, such as those affected by conflict or natural disasters [5].

As of 30 April 2023, 24 countries reported cholera outbreaks globally. The number of cholera outbreaks reported globally in 2022 had increased to 29 compared to an average of 20 reported per year between 2017 and 2021 [6]. Eight countries in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region, namely Afghanistan, Iraq, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Lebanon, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen reported Acute watery diarrhea (AWD)/ cholera cases in 2022. Lebanon and Syria reported cholera outbreaks for the first time that year after almost three decades for Lebanon and two decades for Syria. This is alarming for the whole region, as both countries are not cholera endemic. In 2023, 6 out of 8 countries continued to report AWD/ suspected cholera cases while 2 countries (the Islamic Republic of Iran and Iraq) did not report any cases. Many drivers are contributing to the resurgence of cholera in the Region, including climate change, conflict and political instability, weak health systems, increased population movement, poor water and sanitation infrastructure, and low awareness among the public.

Between 1 January 2022 and 30 April 2023, the highest number of AWD/ suspected cholera cases were reported from Afghanistan (290 406, CFR 0.04%), followed by Syria (111 084, CFR 0.12%), Yemen (23 997, CFR 0.10%), Somalia (21 958, CFR 0.49%), Iraq (11 097, CFR 0.23%), Lebanon (7604, CFR 0.36%), Pakistan (1029 - laboratory-confirmed cases) and Islamic Republic of Iran (360, CFR 1.67%).

the Yemen cholera outbreak began in early October 2016, and by January 2017, the WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (WHO EMRO) considered the outbreak to be unusual in its rapid and wide geographical spread. The serotype of vibrio cholerae O1 involved is Ougawa [7,8] The earliest cases were predominantly in the capital, Sana'a [7] with some occurring in Aden [9]. A total of 268 districts from 20 governorates had reported cases by 21 June 2017 [10]. In 2018, the Ministry of Public Health and Population of Yemen has reported 369 133, with 504 associated deaths (CFR 0.14% (from 1st January 1st to 1December 16, 2018) [11]. It was confirmed by using genomic sequencing, researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and Institut Pasteur concluded that the strain of cholera originated in eastern Africa and was carried to Yemen by migrants.

In 2020, Yemen accounted for 85% of reported cholera cases in the world out of 323 320 cases while only 47 608 cases were reported from other countries [12]. In Marib Governorate, a cholera epidemic began to be recorded in April 2017, seven months after the first case was recorded in the country. Due to political instability, The electronic disease early warning system (EDEWS) was discontinued during the period 2018-2019, and a new system of EDEWS was developed in the governorates under the control of the internationally recognized government (IRG), Marib at the east is one of these governorates where a lot of internally displaced people (IDPs) present and refuges, the aim of this paper is to follow the trend of cholera during the period from January 1st 2002 to 2023 week 45.

Materials And Methods

The setting

The Governorate of Marib is located in the northeastern part of the Republic of Yemen, 173 kilometers to the east of the capital city of Sana’a, between the governorates of Shabwah to the south and Al-Jawf to the north (Figure 1). The governorate is divided into 14 administrative districts with the city of Marib as its capital. https://yemenlg.org/governorates/marib/ . The estimated total population in Marib in 2023 is 1,067,450 According to OCHA’s 2023 Humanitarian Needs Overview for Yemen, there are about 850,000 people in need of assistance in Marib, or 80% of the population, 73% of whom are in dire need. The IDPs population of Ma’rib by December 2022 is 900,000 https://data.humdata.org/dataset/yemen-humanitarian-needs-overview, 2023 People in Need in Yemen.

Figure 1: Map of Yemen present the location of Marib.

Figure 1: Map of Yemen present the location of Marib.

This is a retrospective analysis of the available data from the EDEWS registry. The Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) of in Aden (Yemen) conducted analysis of the available data to describe the trends of the outbreak in Marib governorate. Data of the occurrence of suspected cholera from this analysis are presented in tables and graphs. The reporting period that included in the analysis is from the 1st epi week of 2020 to the 45th epi week of 2023 were obtained from EDEWS. Data were extracted from line lists. The abstracted data were entered and analyzed using Microsoft Excel software (v. 2021).

Data were analyzed in terms of person, place, and time. Frequencies and percentages were used to analyze the study surveillance data from 1st epi week of 2020 to the 45th epi week of 2023. Incidence rate, case fatality rate, and outcome were analyzed.

Results

A total of 4023 suspected Cholera cases were reported to EDEWS in Marib governorate during w1 of 2020 to W45/2023. Three cholera related deaths were reported giving the case fatality rate (CFR) of 0.075%. (Table1)

|

District |

cases |

deaths |

CFR% |

|

Al-Wadi |

2154 |

2 |

0.093 |

|

Marib City |

908 |

0 |

- |

|

Al Jubah |

288 |

0 |

- |

|

Al Abdiyah |

42 |

0 |

- |

|

Jabal Murad |

49 |

0 |

- |

|

Harib |

74 |

1 |

1.351 |

|

Rahabah |

103 |

0 |

- |

|

Raghwan |

99 |

0 |

- |

|

Sirwah |

122 |

0 |

- |

|

Mahliyah |

46 |

0 |

- |

|

Medghal |

98 |

0 |

- |

|

Majzar |

40 |

0 |

- |

|

Total |

4023 |

3 |

0.075 |

Table 1: The cumulative number of suspected cholera cases and deaths in Marib, Yemen w1 2020 to w45 2023 by district.

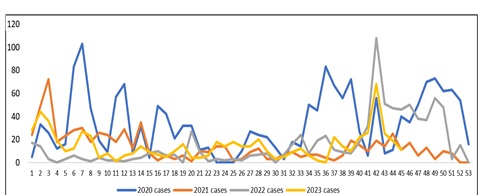

The Epi Curve by years

Clear reduction of the incident cholera cases from 1796 in 2020 to 728 cases in 2021 and 836 cases in 2022 and 446 cases to Epi Week 45 of 2023.

In 2020 seven peaks were observed in the epi curve in Epi weeks 2,7,12,26.36.42 and 49. In 2021; four peaks were observed in Epi weeks 2, 7, 12 and 14. Although, only one peak was observed in 2022 in the Epi week 49, but three peaks were observed in the current year 2023 in the Epi Weeks No 2, 7 and 42 (Figure 2). The surveillance system in Marib be able to investigate 453 suspected cholera case by rapid test, out of them 274 samples were positive for cholera (60%).

Figure 2: Epi curve of cholera suspected cases in marib, 2000-W45/2023.

Figure 2: Epi curve of cholera suspected cases in marib, 2000-W45/2023.

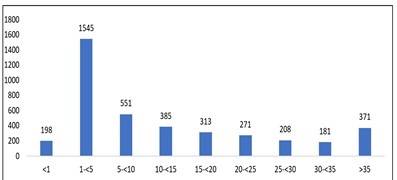

Age and Sex distribution of cholera cases:

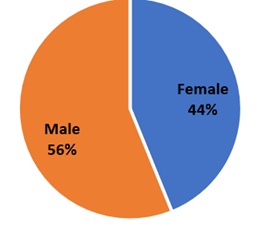

The high proportion of the affected people were children between 1-? 5 years (38%, 1545/4023) followed by age group 5-? 10 years (14%, 551/4023) (Figure 3). Males had the highest recorded cases with 2258 male cases (56%) and 1765 female cases (44%). (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Distribution of cholera cases by age group in marib, 2000-W45/2023.

Figure 4: Distribution of cholera cases by sex in marib, 2000-W45/2023.

Figure 4: Distribution of cholera cases by sex in marib, 2000-W45/2023.

Discussion

The obtained findings showed that the largest number of suspected cases of cholera is in Al-Wadi district and Marib city district, this is due to social and environmental factors like crowding, poor sanitation and accumulation of IDPs a and refugees. Marib Governorate hosts the largest internally displaced population (IDPs) in Yemen, estimated at 900,000 in February 2023 [13]. The population movement made great buren on the social services including drinking water and sanitation. This environmental situation enabled UNICEF WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) project UNICEF to implement three projects to pump potable water in Marib governorate. The projects aim to provide clean water sources to the poorest areas in Yemen, contribute to reducing the incidence of diseases caused by drinking contaminated water, and care for personal hygiene and sanitation in Marib governorate [14]. This intervention may be contributing in decreasing cholera case in 2023. The peak of the outbreak was in 2020 when the COVID19 pandemic is its peak and the social services stop due to the precaution measures were implemented in Marib. The same findings of increasing cholera outbreaks were reported in Africa countries amidst the COVID19 pandemic [15]. Only three cases died with CFR% of 0.075%, the same finding were rported in Hodiedah at western Yemen in 20161nd 2017 (0.09%) [16]. This CFR is within the expectation if the response lead to proper treatment. In other countries like Mali where there is poor response, the CFR was high (8%, 55/ 693 [17] and very high in Cameron (11.6%) [18].

Male to female ratio shows non-significant difference, this is the finding in cholera outbreak in Nigeria where the proportion of affected males and females was about the same (49.00 and 51.00% respectively) [19]. Role of gender in cholera deaths is an issue of controversial findings; in one systematic review of 16 articles, the authors concluded that nine studies did not observe significant differences between men and women while seven studies identified being a male as a risk factor of cholera death [20]. Children under 5 years were the most affected group in Marib, the same findings were observed in certain developing countries like Keyna [21] and Indonesia [22] but in contrast to cholera outbreak in rural areas of Bangladesh were reported the high proportion of cholera cases among children over 15 years [3] and south sudan wehere about 25% of cholera among children at age less than 5 years [23].

At the moment of this analysis, the microbiology culture services were not yet established in the central public health lab in Marib that limit the diagnosis of cholera to the clinical suspicion of acute watery diarrhea. However; alternatively, rapid diagnostic test was used to conform the diagnosis in 60% of the collected samples. In case of outbreak in poor resource contries like Yemen RDT can be used where Culture of PCR are not available although, current cholera RDTs have moderate sensitivity and specificity for detecting Vibrio cholerae Against culture or PCR [24]. The Global Task Force on Cholera Control (GTFCC) recommends that cholera RDTs should have a sensitivity and a specificity of at least of 90% and 85%, respectively [25].

Conclusion

Although Marib is occupied by a large number of IDPs, but the improvement in water supply, good surveillance and food security contributing in reduction of cholera cases in 2023, more over no cholera cases were reported in October 2023 where the diseases is spread in the neighboring governorates. Further studies are needed to follow if there is changes in epidemiology of cholera in Marinfrom epidemic potential to endemicity.

Acknowledgments

The Authors would like to thank all who support this work to be implanted especially FETP program in Yemen, WHO and EMPHNET and MoPH$P for their efforts and provide opportunities for in-service training made our work feasible.

Disclosure of interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/index.html

- Ali M, Nelson AR, Lopez AL, Sack DA (2015) Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9: e0003832.

- Das R, Nasrin S, Palit P, Sobi RA, Sultana AA, et al. (2023)Vibrio cholerae in rural and urban Bangladesh, findings from hospital-based surveillance, 2000-2021. Sci Rep 13:

- Rabbani GH, Greenough WB 3rd (1999) Food as a vehicle of transmission of cholera. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res 17: 1-9.

- Kanungo S, Azman AS, Ramamurthy T, Deen J, Dutta S (2022) Cholera. Lancet (London, England)399: 1429-1440.

- https://www.emro.who.int/pandemic-epidemic-diseases/cholera/acute-watery-diarrhoeacholera-updates-1630-april-2023.html

- Federspiel F, Ali M (2018) The cholera outbreak in Yemen: lessons learned and the way forward.BMC Public Health (Review) 18: 1338.

- https://www.emro.who.int/pandemic-epidemic-diseases/cholera/cholera-cases-in-yemen.html

- https://www.emro.who.int/pandemic-epidemic-diseases/cholera/update-on-the-cholera-situation-in-yemen-30-october-2016.html

- Kennedy J, Harmer A, McCoy D (2017) The political determinants of the cholera outbreak in Yemen. The Lancet. Global Health 5: e970-e971.

- https://www.emro.who.int/pandemic-epidemic-diseases/cholera/outbreak-update-cholera-in-yemen-16-january-2018.html

- https://www.who.int/publications/journals/weekly-epidemiological-record

- https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/shelter-cluster-factsheet-q4-2023-october-december-2023

- https://www.unicef.org/yemen/stories/wash-support-marib-tangible-impact-serving-thousands-people-need

- Oloche O, Priscilla A, Charles O (2021) Cholera in the Era of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Worrying Trend in Africa? International Journal of Public Health 66.

- Altmann M, Suarez-Bustamante M, Soulier C, Lesavre C, Antoine C (2017) First Wave of the 2016-17 Cholera Outbreak in Hodeidah City, Yemen - ACF Experience and Lessons Learned. PLoS Curr 9.

- https://reliefweb.int/report/mali/disease-outbreak-reported-cholera-mali

- Cartwright E, Patel M, Mbopi-Keou F, Ayers T, Haenke B, et al. (2013) Recurrent epidemic cholera with high mortality in Cameroon: Persistent challenges 40 years into the seventh pandemic. Epidemiology & Infection141: 2083-2093.

- Elimian KO, Musah A, Mezue S, Oyebanji O, Yennan S, et al. (2019) Descriptive epidemiology of cholera outbreak in Nigeria, January-November, 2018: implications for the global roadmap strategy. BMC Public Health 19: 1264.

- https://www.gtfcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/gtfcc-risk-factors-of-cholera-mortality.pdf

- Kisera N, Luxemburger C, Tornieporth N, Otieno G, Inda J (2020) A descriptive cross-sectional study of cholera at Kakuma and Kalobeyei refugee camps, Kenya in 2018. Pan African Medical Journal 37: 197.

- Deen JL, von Seidlein L, Sur D, Agtini M, Lucas ME, et al. (2008) The high burden of cholera in children: comparison of incidence from endemic areas in Asia and Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2: e173.

- Jones FK, Wamala JF, Rumunu J, Mawien PN, Kol MT, et al. (2020) Successive epidemic waves of cholera in South Sudan between 2014 and 2017: a descriptive epidemiological study. Lancet Planet Health 12: E577-E587.

- Muzembo BA, Kitahara K, Ohno A, Debnath A, Okamoto K, et al. (2021) Cholera Rapid Diagnostic Tests for the Detection of Vibrio choleraeO1: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel) 11: 2095.

- https://www.gtfcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/gtfcc-interim-use-of-cholera-rapid-diagnostic-tests.pdf

Citation: Mohsen Albaihani AA, Bin-Ghouth AS (2024) Cholera in Marib Governorate, Yemen: Analysis of the Surveillance Data from W1, 2020- w45, 2023. J Community Med Public Health Care 11: 155

Copyright: © 2024 Aziz Awad Mohsen Albaihani, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.