Cross Cultural Adaptation of Berg Balance Scale in Greek for Various Balance Impairments

*Corresponding Author(s):

Lampropoulou SofiaDepartment Of Life And Health Sciences, Technological Educational Institute Of Western Greece, School Of Sciences And Engineering, University Of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

Tel:+357 22842595,

Email:lampropoulou.s@unic.ac.cy

Abstract

Rationale, Aim & ObjectivesThe Berg Balance Scale (BBS) although widely used for assessing balance, it has not been officially adapted into Greek. The aim therefore, of this research is to translate and validate the cross cultural adaptation of the Greek BBS (BBS-GR).

Method The BBS was adapted according to international guidelines, (forward & backward translation, by four bilingual independent translators). The pre-final BBS-GR was piloted by 6 physiotherapists (1-5 years of experience) and 12 patients (5 men & 7 women, age 76±7 years) in the 1st pilot study and by 10 patients (7 men & 3 women, age 57±20 years) during the 2nd pilot study with balance impairments. After modifications, the final BBS-GR was undertaken to 112 patients (43 men, 69 women, age 67±19 years) for its psychometric testing. It was administered by two raters, twice over a 10 day period, to assess both inter- and test-retest reliability correspondingly. Bland-Altman analysis presented the levels of agreement between measurements. Validity was assessed by correlation of the BBS-GR with the mini-Balance Evaluation Systems Test (mini-BESTest-GR), the Functional Reach Test (FRT), the Timed Up and Go test (TUG) and the questionnaire of Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I).

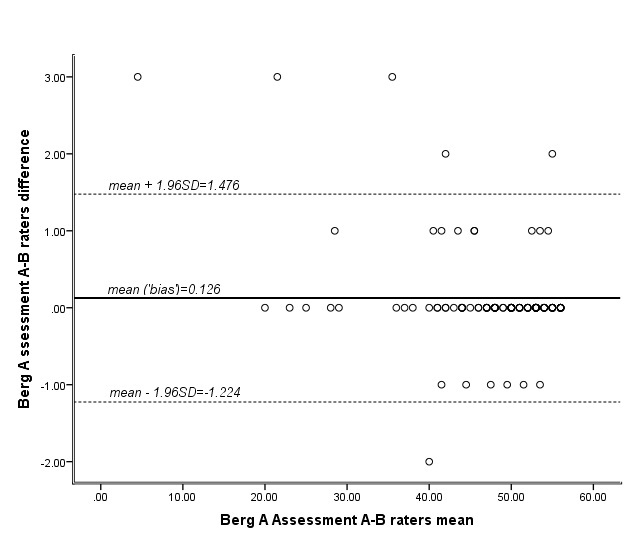

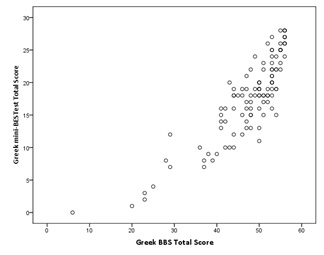

ResultsMinor modifications to one item were required for the final BBS-GR version, and showed: excellent inter-rater reliability (ICC=0.998), test-retest (ICC=0.976) reliability and internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=0.830). Measurements showed a good level of agreement (meandif=0.126±0.7, p>0.05). Spearman’s correlations coefficient (rs) were strong between the BBS-GR and the mini-BESTest (rs=0.844, p<0.001), the TUG (rs=-0.781, p<0.001), the FRT (rs=0.650, p<0.001) and FES-I (rs=-0.501, p<0.001), indicating good validity properties. Responsiveness across fallers and non fallers showed a moderate effect size (0.54).

ConclusionThe excellent psychometric characteristics of the Greek BBS highly recommend its utility to the Greek clinical setting. Further research should be undertaken to evaluate responsiveness over treatment conditions.

Keywords

BBS; Balance; Cross-cultural adaptation; Greek; Reliability; Validity

INTRODUCTION

The Berg Balance Scale (BBS) [1] constitutes a popular and well established clinical tool for the assessment of balance [2]. It is mainly known as a tool for measuring balance in the elderly [1,3,4] but it has also been tested for its reliability and validity in assessing balance in patients with various neurological diseases, such as stroke [5-7], multiple sclerosis [8], traumatic brain injury [9] and Parkinson’s disease [10] with very good results. The BBS also predicts prospective falls in the elderly although it is highly recommended that it also be administered with other outcome measures [11,12].

In relation to other scales of assessing static and dynamic balance, such as the Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment (POMA) or the Balance Evaluation Systems Test (BESTest), the BBS has the advantage of being an easy and quickly administered physical performance test that does need no training or special equipment [13]. The BBS consists of 14 balance tasks such as sitting-to-standing, standing-to sitting, transferring from bed to chair, sitting and standing unsupported, standing with eyes closed, standing with feet together, tandem standing, single limb standing, reaching forward, picking up an object from the floor, alternating foot on stool, looking over the shoulders, and turning 360° [1]. Every task is scored in a 5-point ordinal scale (0-4) and total score ranges from 0 to 56 with higher scores indicating better performance and greater independence [13]. A cut off point of 45/56 has been suggested for independent and safe ambulation [3]. All tasks take no more than 15 minutes to be delivered whereas the BESTest usually takes more than 40 minutes to administer [14]. In addition, compared to single balance tests such as the Romberg’s Test, the Functional Reach Test (FRT) or the Timed Up and Go test (TUG), BBS, with the 14 aforementioned functional tasks that it includes, offers a thorough assessment of balance [15,16]. Finally, it is freely available and inexpensive. Thus, the BBS offers several advantages for international adoption for balance assessment [13].

BBS has been adapted into several languages, including Italian [17], Brazilian-Portuguese [18], German [19], Korean [20], Swedish [4], Norwegian [21], Turkish [22], French [23], and Persian [24,25]. Most translations to the target language have been undertaken according recommendations of using double directed (forward and backward) translation process [17-21]. Psychometric characteristics of reliability and validity of the adapted versions are shown in table 1. Almost all adapted versions showed high intra- and inter-rater reliability and internal consistency [4,18,20,22,24,25]. The Italian [17], Turkish [22], Brazilian-Portuguese [26] and French [23] versions presented good construct and criterion validity in correlation with other balance measurements.

| Adapted version | Study | Sample | Reliability | Validity (correlation with BBS) |

| Italian | Ottonello et al. [17] | N=85 Neuro/msk |

Inter-rater (ICCC=0.99) Cronbach' α=0.95 |

TBS (r=0.96*) |

| Brazilian/portuguese |

Miyamoto et al. [18] Scalzo et al. [26] |

N=36 Elderly N=53 PD |

Inter-rater (ICCC=0.99) |

- |

| Korean | Jung et al. [20] | N=18 Stroke |

Inter-rater (ICCC=0.97) Inter-rater (ICCC=0.97 physio) (ICCC=0.95 physiatrists) |

- |

| Norwegian | Halsaa et al. [21] | N=83 Elderly |

Inter-rater (ICCC=0.988) Cronbach' α=0.87 |

- |

| Swedish | Conradsson et al. [4] | N=45 Elderly |

Inter-rater (ICCC=0.97) | - |

| Turkish | Sahin et al. [22] | N=60 Elderly |

Inter-rater (ICCC=0.98) Inter-rater (ICCC=0.97) |

MBI (r=0.67*) TUG (r=-0.75*) |

| French | Lemay & Nadeau [23] | N=32 SCI |

- | WISCI II (r=0.816*) SCI-FAImobility (0.740*) SCI-FAIparameter (0.747*) SCI-FAIassistive devices (0.714*) 2MWT (r=0.781*) 10MWT (r=0.792*) TUG (r=-0.815*) |

| Persian | Azad et al. [24] Salavati et al. [25] |

50 MS |

Inter-rater (ICCC=0.99) Cronbach' α=0.9 Intra-rater (ICC=0.95) Inter-rater (ICCC=0.93) Cronbach' α=0.62 |

- |

Table 1: Psychometric characteristics of adapted versions of Berg Balance Scale (BBS).

HY: Hoehn & Yahr Staging Scale

FIM: Functional Independence Measure

MBI: Modified Barthel Index

MS: Multiple Sclerosis

2MWT: 2-min walk test

10MWT: 10-min walk test

PD: Parkinson Disease

S & E: Schwab and England Scale

SCI-FAI: Spinal Cord Injury Functional Ambulation Inventory

TBS: Tinetti Balance Scale

TUG: Timed Up and Go

UPDRS II & III: Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (Subscales II & III)

WISCI II: Walking Index for Spinal Cord Injury (Version II)

*p<0.05

Despite its popularity, BBS has not been cross culturally adapted into the Greek language and setting. A Greek study of Chatzitheodorou et al., [27] tested its reliability regarding gender and the falls’ history in 60 elderly with very good results, but this study did not refer to any kind of official translation of the scale with consideration of cross cultural adaptation guidelines and no evaluation of cross cultural validation in Greek has been undertaken. Therefore, the aim of this study is to cross culturally adapt and validate the BBS in Greek adults with balance impairments. An officially translated and scientifically adapted tool would be of great value for a valid balance assessment in Greek patients.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study followed three phases. Firstly, a translation of the BBS into Greek was conducted after receiving permission of the original instrument’s developer, Dr. Berg. Secondly, a piloting testing of the pre-final version (derived in the initial phase) of the Greek BBS (BBS-GR) followed. Finally, full psychometric evaluation of the final BBS-GR was undertaken including reliability, validity and responsiveness of the measurement tool. The study was approved by ethics review board of the Scientific Committee of the Technological Educational Institute (TEI) of Western Greece.

Translation of the scale

Pilot study

Psychometric testing of the final Greek version of BBS

Outcome measures: Balance assessment tools were selected for comparison with the BBS to test its validity. The mini-Balance Evaluation Systems Test (mini-BESTest) is a recently developed balance tool, and it is the short version of the original BESTest [33]. It was chosen because, similarly to BBS, it consists of 14 functional balance tasks of static and dynamic balance, and it takes 15 minutes to be delivered. Its advantage to other functional balance scales is that its tasks are divided into five balance testing systems (anticipatory adjustments, reactive control, compensatory stepping corrections, sensory orientation and dynamic balance during gait) offering the benefit of identification of the system responsible for the balance deficit [33,34]. Its excellent reliability, its strong correlation with the BBS and other balance measures [30,31,34,35] and its availability to Greek language (www.bestest.us) makes it one of the best choices for comparison with the Greek version of the BBS. The Timed Up and Go Test (TUG) [13,36] and the Functional Reach Test (FRT) [37] are simple balance tests which were chosen due to their high correlation with the BBS, their reliability, their ability to predict falls and because these are of the most frequently simple tests used in clinical and similar research settings [15,38,39]. Additionally to observational assessment tools, balance was self-reported by the participants through the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I) questionnaire [40]. Its excellent psychometric characteristics in exploring the chance of fall in everyday living activities as well as its availability in the Greek language [32] made its selection the best choice for the validity assessment of the Greek version of the BBS.

Procedure: All measurements administered in outpatients settings, including patient’s homes, quiet environment to avoid attention disturbance, and at a convenient time for them, but not close to meals or close to medication times. Patients had been advised in advance to wear comfortable clothes and flat shoes. Apart from the demographic characteristics, patients were asked about how often they had fallen during the last year with answer choices of “neverâ€, “onceâ€, “twiceâ€, “more than two timesâ€. At the same time, the FES-I was also completed by the patient. The functional balance tests (BBS, mini-BESTest, TUG, FRT) were then undertaken. After completion of the BBS a 10 minutes break was taken before the administration of the mini-BESTest to eliminate fatigue from the tasks.

Reliability: Reliability concerns the degree of similarity/stability in answers taken in repeated measures (41). To evaluate the test-retest reliability, measurements were repeated 7-10 days after the first testing. During the first session two observers scored the patient performance independently, to examine the inter-rater reliability. Raters for psychometric testing of the BBS-GR were two physiotherapists of those participating to the 1st pilot study. These procedures (7-10 days between tests time-interval and at least two raters) for reliability assessment were followed by other BBS cross cultural adaptation studies [18]. The internal consistency reliability, which measures the degree that the items of the scale are correlated and thus measuring the same concept was also evaluated [41].

Validity: Validity is referred to the degree to which an instrument measures what it is intended to measure [42]. Criterion validity is used to demonstrate the instrumental validity by comparing the scale being tested with a criterion measure of a same construct that has been established as valid [43]. For the criterion validity, the BBS-GR was correlated with the Greek version of mini-BESTest, previously assessed as having very good (construct) validity with Greek patients with balance disorders [44]. The BBS-GR was also tested for its construct validity (specifically the convergent validity) through the agreement among ratings that have been selected independently by other measurement scales that theoretically should be related [43]. For the convergent validity the final Greek version of BBS was correlated with the TUG, the FRT, and the Greek FES-I.

Responsiveness: BBS-GR was also assessed for its responsiveness, meaning its ability to detect a clinically significant change [45]. However, in the absence of intervention, responsiveness could be used to assess the ability of a measurement tool to reflect change according to an external standard (i.e., to classify patients in two categories) [46]. Responsiveness was assessed through the differences between the two big categories, of “fallers†and “non fallersâ€, where as “fallers†are characterized those who experienced at least one unexplained fall during the last year and “non fallers†those who had not one fall [32].

Ceiling & floor effects: Ceiling and floor effects of the BBS-GR were examined to assure that no great proportion of the testing sample have scores at the bottom (floor) or top (ceiling) of the scale and thus the measurement outcome is able to detect change in performance and does not limit sensitivity [47].

DATA ANALYSIS

Tests of all data for normality by use of Kolmogorov-Smirnov test were significant so nonparametric tests were used. Criterion and construct validity were investigated by using Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rs). Correlation between 0.0-0.25 indicates little if any association, 0.26-0.49 low association, 0.50-0.69 moderate association, 0.70-0.89 high association and 0.90-1.00 very high association [48]. Relative reliability was assessed by computing the consistency of the two measurements using Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC2,2) where values 0.75 excellent reliability [8,45]. The Bland Altman Analysis for absolute reliability was also used to plot the differences between the two measurements against the means for each subject and to show the ‘bias’ (mean difference) of the measurements and the 95% Limits of Agreement (LoA) [49,50]. One Sample t-test for the differences was used to find whether these measurements significantly differed from 0. The internal consistency reliability was measured with the Cronbach's alpha coefficient with accepted value of 0.70 (or 70%), values between 0.70 and 0.80 to demonstrate good internal consistency and values above 0.80 to indicate very good internal consistency [32,48]. Responsiveness of the BBS-GR was calculated as the ratio between the mean difference of the scores between “fallers†and “non fallers†divided by the standard deviation of the baseline score (total score of “fallers†and “non fallers†together) [32,46]. That ratio was considered as the effect size with the value of 0.2 to 0.5 to indicate a small effect, value from 0.5 to 0.8 a moderate and above 0.8 a large effect [51]. Percentage more than 20% of the participants at the highest and lowest score was considered as ceiling and floor effects, accordingly. Skewness of scores distribution, as further estimator of ceiling & floor effect, was presented at total scores [35]. All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (mean±SD), and statistical significance was set at p≤0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (version 17.0, SPSS for Windows, Chicago, SPSS Inc).

RESULTS

Translation and adaptation of the scale

| Stages | Translation Procedure | Words/Phrases that needed attention/modification | Final Wording (Meaning in English) |

| 1ο | Forward Translation (English-Greek) | Without Difficulties | |

| 2ο | Synthesis I | Item Subject Reaching forward |

ΛειτουÏγική ΔÏαστηÏιότητα (Functional task)Εξεταζόμενος (Examinee) ΤÎντωμα Ï€Ïος τα εμπÏός (Stretching forward) First Greek BBS |

| 3ο | Backward Translation Greek- English | Τεντωθειτε μπÏοστα (Stretch forward) ΓυÏιστε να κοιτάξτε κατευθείαν πίσω (Turn to look directly behind) Κάντε μια πλήÏη πεÏιστÏοφή (Doafullturn) |

Lean forward Turn around to look straight behind Perform a full rotation |

| 4ο | Synthesis II | Turn back Rotate Steps |

ΓυÏίστε Ï€Ïος τα πίσω (Turnback) ΣτÏίψτε (Rotate) Πατήματα (Touch) 1st pre-final Greek BBS |

| 5ο | 1st Pilot Testing 2nd Pilot Testing |

Difficulty in understanding “turn back” & “rotate 360°” (from patients) All clear and comprehensive |

Item 10 Instructions: Turn to look directly behind over your left shoulder, without moving your feet from floor (Underlined phrase added in Greek version after permission) Item 11 Instructions:Turn completely around in a full circle, with small steps (Underlined phrase added in Greek version after permission) 2nd pre-final Greek BBS No more modifications needed Final Greek BBS (BBS-GR) |

Psychometric testing of the final Greek version of BBS

| Characteristics | Percentage (Number) |

Mean Score ± SD (Range) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 38% (43) | 48±9 (23-56) |

| Female | 62% (69) | 47±9 (6-56) |

| Condition causing Balance Impairment | ||

| Imbalance (Age related) | 37% (42) | 50±5 (37-56) |

| Musculoskeletal | 19% (21) | 46±8 (23-56) |

| Stroke | 15% (18) | 44±14 (6-56) |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 8% (9) | 49±5 (41-56) |

| Parkinson | 8% (9) | 47±5 (39-53) |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | 4% (4) | 55±3 (50-56) |

| Cerebellum Inflammation | 3% (3) | 33±18 (20-53) |

| Blindness | 2% (2) | 51±0 (51-51) |

| Cerebrum Inflammation | 2% (2) | 54±3 (52-56) |

| Hydrocephalus | 1% (1) | 49±0 (49-49) |

| Drop Foot | 1% (1) | 56±0 (56-56) |

| Falls over last year | ||

| 0 | 61% (69) | 50±6 (6-56) |

| 1 | 37% (41) | 45±9 (20-56) |

| ≥2 | 2% (2) | 46±3 (44-48) |

Table 3: Demographic characteristics of the Greek sample (n=112).

Reliability

| Intraclass Correlation Coefficient | ||

| Item | Inter-rater | Test-retest |

| 1 | 0.972* | 0.990* |

| 2 | 1.000* | 0.913* |

| 3 | 0.983* | 0.967* |

| 4 | 0.902* | 0.955* |

| 5 | 0.995* | 0.931* |

| 6 | 0.984* | 0.786* |

| 7 | 0.975* | 0.837* |

| 8 | 0.982* | 0.871* |

| 9 | 0.995* | 0.893* |

| 10 | 0.976* | 0.888* |

| 11 | 0.995* | 0.830* |

| 12 | 0.999* | 0.961* |

| 13 | 1.000* | 0.894* |

| 14 | 0.999* | 0.856*` |

Figure 1: Bland Altman Plot of the difference scores of the two raters measurements in total BBS scores of the sample (n=112) during the first assessment. LoA as the mean difference±1.96SD are presented.

Validity

| Measurement Outcome | Spearman’s rho (r) |

| Mini-BESTest | 0.844* |

| TUG | -0.781* |

| FRT | 0.650* |

| FES | -0.501* |

*Statistically Significant Correlation at p<0.001

Responsiveness

Ceiling & floor effects

| Measurement Outcome |

Mean Score±SD |

Skewness |

Floor Effect |

Ceiling Effect |

| BBS | 48±8 | -2.072 | 0% (0) | 9% (10) |

| Mini-BESTest | 18±6 | -0.594 | 0.9% (1) | 2.7% (3) |

| TUG | 16±9 | 2.901 | -* | -* |

| FRT | 19±6 | 0.344 | 0% (0) | -* |

| FES | 33±12 | 0.793 | 1.8% (2) | 3.6% (4) |

*Not applicable

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to cross culturally adapt and validate the BBS into Greek for patients with balance impairments. The main findings in regards the translation and the validation process are discussed and interpreted below.

Translation

Psychometric Testing of the Greek version of BBS

In this part of the study the psychometric properties of the BBS-GR for people with various balance deficits were examined. The first results showed that the BBS-GR has high criterion validity and moderate to high convergence validity. Its ability in giving stable results over time and between raters was proved by the excellent test-retest and inter-rater reliability. No ceiling or floor effects were revealed thus arguing towards the ability of the scale to detect changes in performance. The negative skewness in the distribution of the scores in combination with the moderate responsiveness of the scale may be explained by the sample used in the present study, which consisted of ambulatory patients.

The BBS-GR showed high criterion validity with the Greek mini-BESTest. Other language translations of the BBS have not been correlated with the mini-BESTest probably because this scale has only recently been developed [33]. However, similar results of high correlation between the two scales have been recorded in other validity studies for the mini-BESTest. Specifically, in the studies of Bergstorm et al., [29], Godi et al., [30], Tsang et al., [35] correlations of 0.86, 0.85 and 0.83 respectively, were reported when the scales have been administered to patients with stroke and balance impairments. Our lower correlation of the BBS-GR with the TUG is similar to correlations for the Persian [25] and Turkish study [22], which reported a correlation value of 0.74 and 0.75 respectively. The moderate correlation of the BBS-GR with the FRT that yielded in our study, is not in agreement with the study of Smith et al., [52], which was conducted in 75 patients with stroke (r=0.78). The results may be explained by the differences between our study which included participants with varied neurological conditions, and the Smith et al study [52] which used a more homogeneous sample consisting of stroke patients. Our results were more similar to that of Kuruka et al., [53] who showed a more moderate correlation (r=0.48) based on a sample of 30 healthy elderly woman. A moderate correlation of BBS-GR with the FES-I questionnaire, which was revealed in the present study, may be expected due to the indirect way that the FES-I assesses balance, which in contrary to the BBS that assesses it via tasks performance, FES-I is based on subjective reports from the patient. Moderate correlations between BBS and other scales, such as the Modified Barthel Index [22], the Modified Hoehn and Yahr Staging Scale [10] or the Schwab & England Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scale [26], have been attributed to less closely relation of these scales with balance performance. The high correlation between BBS and FES-I scales in the study of Wirz et al., [54] may be attributed to homogeneity of their sample which consisted of spinal cord injured patients only. The moderate and high correlations of the BBS-GR with the TUG, FRT and FES-I balance tools that have been revealed in the present study indicate a moderate to high convergence validity of the BBS-GR.

The BBS-GR showed both excellent test-retest and inter-rater reliability as it was assessed by the ICC of the scores between repeated measurements and scores between observers. In addition to excellent relative reliability, BBS-GR showed absolute reliability as this was proved by the Bland Altman Analysis. The mean difference between the measurements of the two raters were close to 0 and 95% of the cases were lying between the limits of agreement proving the absence of proportional bias in the measurements [48]. The high correlation and the agreement between the measurements indicate that the scale is reliable in presenting stable repeated results. These excellent results are in agreement with many of the other language versions of the BBS [18,20,22,25]. In addition, a systematic review of 11 studies that assessed intra- and inter-rater reliability of the English BBS in a variety of clinical populations revealed a value of 0.98 for the intra-rater reliability and 0.97 for inter-rater reliability [55]. Our findings with the BBS-GR also have very similar correlations. An excellent correlation was presented not only in the total score of the scale but also in the score of every item. The inter-rater reliability for each item ranged from 0.972 to 1.00 and the test-retest reliability ranged from 0.786 to 0.99, values that are close enough to those reported in the Brazilian BBS [18], the Iranian BBS [24], the Norwegian BBS [21] and in the original BBS [1,5]. The high internal consistency of the BBS-GR (0.83) indicates the homogeneity of the scale and is in line with the Norwegian (0.87) [21], the Italian (0.95) [17], and the Turkish versions (0.98 at total score) [22]. The Iranian scale has presented lower internal consistency (0.62) [25].

The Greek BBS-GR did not present any ceiling or floor effects, but compared to other scales it showed the biggest percentage in people at highest score. In a systematic review of 21 studies in people with stroke three studies reported a ceiling or/and floor effect of the BBS [2]. In addition, the study of Tsang et al. [35] did also report a larger ceiling effect of 32% for BBS. The negative skew, reported to our study, with more scores gathered to the higher levels, agree with the studies of Sahin et al., [22] and Tsang et al., (35). These results may be explained by the characteristics of the sample in which all patients were ambulant, as the inclusion criteria required, which however may skew the scores towards higher levels. The same characteristics may also explain the moderate responsiveness also presented here. Nevertheless, the mean total BBS-GR score in the group of “fallers†did not differ too much from the “non fallers†BBS-GR score (Table 3), thus leading to moderate effect size. Additionally, the variability in the sample characteristics may have masked the responsiveness results. This finding implies that the BBS-GR of scores equal or above 20/56 in various balance impairments cannot actually distinguish “fallers†from “non-fallersâ€. Further application of the BBS-GR to a less varied sample according to neurological conditions, and including non-ambulant patients as well, may give more concluding results regarding the skewness and the responsiveness of the scale.

Study Limitations

Implications for further research

CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

STATEMENT

Part of the results have been orally presented to 24ο Panhellenic Scientific Conference of Physiotherapy, PSF, Athens, Greece (5-7 Dec. 2014).

REFERENCES

- Berg KO, Wood-Dauphinee SL, Williams JI, Maki, B (1989) Measuring balance in the elderly: preliminary development of an instrument. Canadian Journal of Public Health 41: 304 - 311.

- Blum L, Korner-Bitensky N (2008) Usefulness of the Berg Balance Scale in stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review. Phys Ther 88: 559-566.

- Berg KO, Wood-Dauphinee SL, Williams JI, Maki B (1992) Measuring balance in the elderly: validation of an instrument. Can J Public Health 83: 7-11.

- Conradsson M, Lundin-Olsson L, Lindelöf N, Littbrand H, Malmqvist L, et al. (2007) Berg balance scale: intrarater test-retest reliability among older people dependent in activities of daily living and living in residential care facilities. Phys Ther 87: 1155-1163.

- Berg K, Wood-Dauphinee S, Williams JI (1995) The Balance Scale: reliability assessment with elderly residents and patients with an acute stroke. Scand J Rehabil Med 27: 27-36.

- Stevenson TJ (2001) Detecting change in patients with stroke using the Berg Balance Scale. Aust J Physiother 47: 29-38.

- Flansbjer UB, Blom J, Brogårdh C (2012) The reproducibility of Berg Balance Scale and the Single-leg Stance in chronic stroke and the relationship between the two tests. PM R 4: 165-170.

- Toomey E, Coote S (2013) Between-rater reliability of the 6-minute walk test, berg balance scale, and handheld dynamometry in people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 15: 1-6.

- Newstead AH, Hinman MR, Tomberlin JA (2005) Reliability of the Berg Balance Scale and balance master limits of stability tests for individuals with brain injury. J Neurol Phys Ther 29: 18-23.

- Qutubuddin AA, Pegg PO, Cifu DX, Brown R, McNamee S, et al. (2005) Validating the Berg Balance Scale for patients with Parkinson's disease: a key to rehabilitation evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 86: 789-792.

- Muir SW, Berg K, Chesworth B, Speechley M (2008) Use of the Berg Balance Scale for predicting multiple falls in community-dwelling elderly people: a prospective study. Phys Ther 88: 449-459.

- Neuls PD, Clark TL, Van Heuklon NC, Proctor JE, Kilker BJ, et al. (2011) Usefulness of the Berg Balance Scale to predict falls in the elderly. J Geriatr Phys Ther 34: 3-10.

- Hayes KW, Johnson ME (2003) Measures of adult general performance tests: The Berg Balance Scale, Dynamic Gait Index (DGI), Gait Velocity, Physical Performance Test (PPT), Timed Chair Stand Test, Timed Up and Go, and Tinetti Performanceâ€Oriented Mobility Assessment (POMA). Arthritis Care & Research 49: 28-42.

- Horak FB, Wrisley DM, Frank J (2009) The Balance Evaluation Systems Test (BESTest) to Differenciate Balance Deficits. Phys Ther 89: 484-498.

- Yelnik A, Bonan I (2008) Clinical tools for assessing balance disorders. Neurophysiol Clin 38: 439-445.

- Tyson SF, Connell LA (2009) How to measure balance in clinical practice. A systematic review of the psychometrics and clinical utility of measures of balance activity for neurological conditions. Clin Rehabil 23: 824-840.

- Ottonello M, Ferriero G, Benevolo E, Sessarego P, Dughi D (2003) Psychometric evaluation of the Italian Version of the Berg Balance Scale in rehabilitation inpatients. Europa Medicophysica 39: 181-189.

- Miyamoto ST, Lombardi Junior I, Berg KO, Ramos LR, Natour J (2004) Brazilian version of the Berg balance scale. Braz J Med Biol Res 37: 1411-1421.

- Scherfer E, Bohls C, Freiberger E, Heise KF, Hogan D (2006) Berg-Balance-Scale - German Version - Translation of a Standardized Instrument for the Assessment of Balance and Risk of Falling. Physioscience 2: 59-66.

- Jung HY, Park JH, Shim JJ, Kim MJ, Hwang MR, et al. (2006) Reliability Test of Korean Version of Berg Balance Scale. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med 30: 611-618.

- Halsaa KE, Brovold T, Graver V, Sandvik L, Bergland A (2007) Assessments of interrater reliability and internal consistency of the Norwegian version of the Berg Balance Scale. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 88: 94-98.

- Sahin F, Yilmaz F, Ozmaden A, Kotevolu N, Sahin T, et al. (2008) Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the Berg Balance Scale. J Geriatr Phys Ther 31: 32-37.

- Lemay JF, Nadeau S (2010) Standing balance assessment in ASIA D paraplegic and tetraplegic participants: concurrent validity of the Berg Balance Scale. Spinal Cord 48: 245-250.

- Azad A, Taghizadeh G, Khaneghini A (2011) Assessments of the reliability of the Iranian version of the Berg Balance Scale in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Taiwan 20: 22-28.

- Salavati M, Negahban H, Mazaheri M, Soleimanifar M, Hadadi M, et al. (2012) The Persian version of the Berg Balance Scale: inter and intra-rater reliability and construct validity in elderly adults. Disabil Rehabil 34: 1695-1698

- Scalzo PL, Nova IC, Perracini MR, Sacramento DR, Cardoso F, et al. (2009) Validation of the Brazilian version of the Berg balance scale for patients with Parkinson's disease. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 67: 831-835.

- Chatzitheodorou E, Aggelousis N, Michalopoulou M, Gourgoulis B (2006) Reliability of Berg Balance Scale in healthy Greek elderly. Physiotherapy Issues 4: 13-20.

- Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W (2011) Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract 17: 268-274.

- Bergström M, Lenholm E, Franzén E (2012) Translation and validation of the Swedish version of the mini-BESTest in subjects with Parkinson's disease or stroke: a pilot study. Physiother Theory Pract 28: 509-514.

- Godi M, Franchignoni F, Caligari M, Giordano A, Turcato AM, et al. (2013) Comparison of reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the mini-BESTest and Berg Balance Scale in patients with balance disorders. Phys Ther 93: 158-167.

- King LA, Priest KC, Salarian A, Pierce D, Horak FB (2012) Comparing the Mini-BESTest with the Berg Balance Scale to Evaluate Balance Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinsons Dis.

- Billis E, Strimpakos N, Kapreli E, Sakellari V, Skelton DA, et al. (2011) Cross-cultural validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I) in Greek community-dwelling older adults. Disabil Rehabil 33: 1776-84.

- Franchignoni F, Horak F, Godi M, Nardone A, Giordano A (2010) Using psychometric techniques to improve the Balance Evaluation Systems Test: the mini-BESTest. J Rehabil Med 42: 323-331.

- Leddy AL, Crowner BE, Earhart GM (2011) Utility of the Mini-BESTest, BESTest, and BESTest Sections for Balance Assessments in Individuals with Parkinson Disease. J Neurol Phys Ther 35: 90-97.

- Tsang CS, Liao LR, Chung RC, Pang MY (2013) Psychometric properties of the Mini-Balance Evaluation Systems Test (Mini-BESTest) in community-dwelling individuals with chronic stroke. Phys Ther 93: 1102-1115.

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S (1991) The timed “Up & Goâ€: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 39: 142-148.

- Duncan PW, Studenski S, Chandler J, Prescott B (1992) Functional reach: predictive validity in a sample of elderly male veterans. J Gerontol 47: 93-98.

- Behrman AL, Light KE, Flynn SM, Thigpen MT (2002) Is the functional reach test useful for identifying falls risk among individuals with Parkinson’s disease?. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 83: 538-542.

- Mancini M, Horak FB (2010) The relevance of clinical balance assessment tools to differentiate balance deficits. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 46: 239-248.

- Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K, Kempen G, Piot-Ziegler C, et al. (2005) Development and initial validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age Ageing 34: 614-619.

- Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, et al. (2007) Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 60: 34-42.

- Kimberlin CL, Winterstein AG (2008) Validity and reliability of measurement instruments used in research. Am J Health Syst Pharm 65: 2276-2284.

- Bannigan K, Watson R (2009) Reliability and validity in a nutshell. J Clin Nurs 18: 3237-3243.

- Michailidi F, Skrinou D, Chandrinou D, Meligoni M, Tsala A, et al. (2014) Psychometric Characteristics of Greek mini-BESTest. 24th Pan-Hellenic Scientific Congress of Physiotherapy. Oral Presentation.

- Roach KE (2006) Measurement of Health Outcomes: Reliability, Validity and Responsiveness. Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics 18: 8-12.

- Husted JA, Cook RJ, Farewell VT, Gladman DD (2000) Methods for assessing responsiveness: a critical review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol 53: 459-68.

- Scrivener K, Schurr K, Sherrington C (2014) Responsiveness of the ten-metre walk test, Step Test and Motor Assessment Scale in inpatient care after stroke. BMC Neurol 14: 129.

- Munro B (2005) Statistical methods for health care research, (55th edn), Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA.

- Myles PS, Cui J (2007) Using the Bland-Altman method to measure agreement with repeated measures. Br J Anaesth 99: 309-311.

- Atkinson G, Nevill AM (1998) Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med 26: 217-238.

- Hsieh YW, Wu CY, Lin KC, Chang YF, Chen CL, et al. (2009) Responsiveness and validity of three outcome measures of motor function after stroke rehabilitation. Stroke 40: 1386-1391.

- Smith PS, Hembree JA, Thompson ME (2004) Berg Balance Scale and Functional Reach: determining the best clinical tool for individuals post acute stroke. Clin Rehabil 18: 811-818.

- Karuka AH, Silva JA, Navega MT (2011) Analysis of agreement of assessment tools of body balance in the elderly. Rev Bras Fisioter 15: 460-466.

- Wirz M, Müller R, Bastiaenen C (2010) Falls in persons with spinal cord injury: validity and reliability of the Berg Balance Scale. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 24: 70-77.

- Downs S, Marquez J, Chiarelli P (2013) The Berg Balance Scale has high intra- and inter-rater reliability but absolute reliability varies across the scale: a systematic review. J Physiother 59: 93-99.

- Downs S, Marquez J, Chiarelli P (2014) Normative scores on the Berg Balance Scale decline after age 70 years in healthy community-dwelling people: a systematic review. J Physiother 60: 85-89.

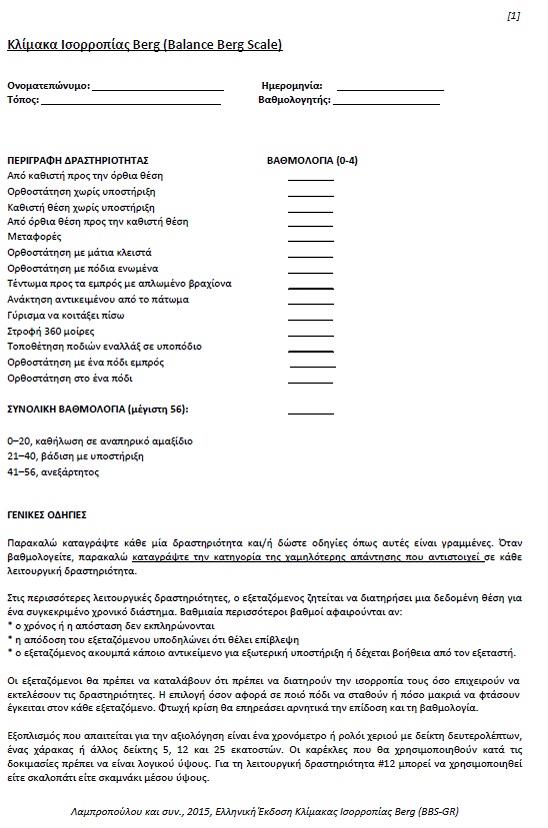

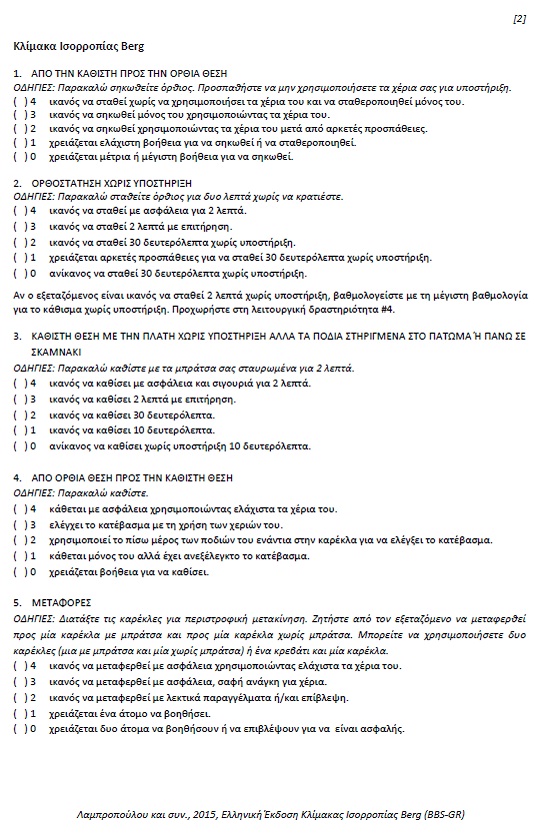

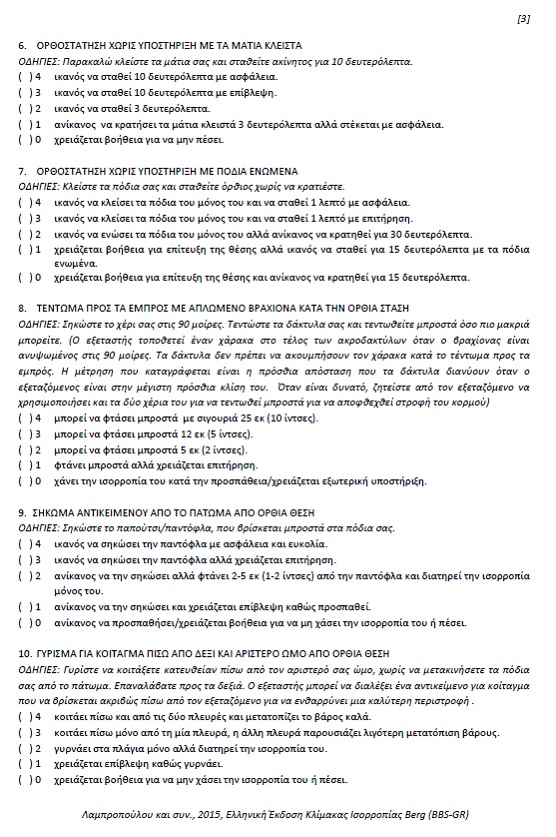

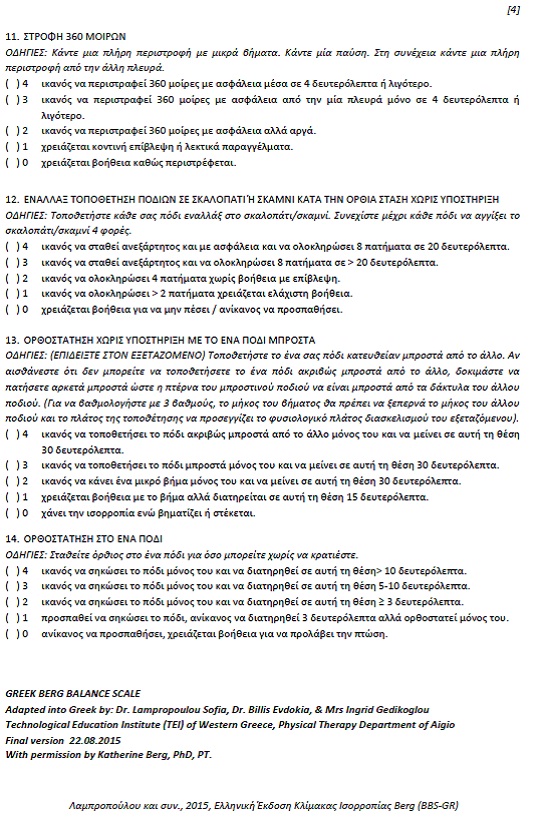

APPENDIX

Appendix I: Berg Balance Scale translated into Greek.

Citation: Lampropoulou S, Gizeli A, Kalivioti C, Billis E, Gedikoglou IA, et al. (2016) Cross Cultural Adaptation of Berg Balance Scale in Greek for Various Balance Impairments. J Phys Med Rehabil Disabil 2: 011.

Copyright: © 2016 Lampropoulou Sofia, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.