Disaster Preparedness among Nepalese Students Residing in Japan

*Corresponding Author(s):

Aliza K C BhandariGraduate School Of Public Health, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan

Email:18mp204@slcn.ac.jp / 20dp001@slcn.ac.jp

Abstract

Background: Japan is one of the most disaster-prone countries. Nepalese students coming to Japan are relatively young and perhaps unaware of the disaster management system of Japan. Thus, this study aims at identifying the perceived knowledge, attitude and practice regarding disaster preparedness among Nepalese students coming to Japan and to identify the factors associated with their preparedness practice.

Methods: This study utilized the data from a cross sectional study conducted among Nepalese immigrants residing in Japan. The respondents with their residency status as students were selected for this analysis. Multivariable linear regression analysis was conducted to identify the factors associated with the practice of Nepalese students regarding disaster preparedness

Results: This study included total of 404 participants, 96 of them were students and 308 were non-students. The mean age of students was 26.51 ± 94 and about 65% of them were male. Mean knowledge score was 22.63 ± 5.73 and mean practice score was 16.04 ± 5.91 among students regarding disaster preparedness. Knowledge and use of smart phone to collect information were associated with the disaster preparedness practice.

Conclusions: This study observed that the perceived knowledge and practices regarding natural disasters are very poor among Nepalese students residing in Japan. Several disaster drills and practice sessions at the educational institutions like Japanese language schools, universities, etc. could help to increase the knowledge, attitude and practice regarding disaster preparedness among students.

Keywords

Disaster preparedness; Immigrants, Japan; Nepalese; Natural disaster

List of Abbreviations

IFRCS: International Federation of Red Cross Society

EED: Emergency Events Database

GDP: Gross Domestic Product

US: United States

USD: United States Dollar

NRNA: Non-Residential Nepalese Association

CVR: Content Validity Ratio

FGD: Focus Group Discussion

CVI: Content Validity Index

I-CVI: Item level Content Validity Index

S-CVI: Scale level Content Validity Index

IRB: International Review Board

UK: United Kingdom

SEE: Secondary Education Examination

aOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio

CI: Confidence Interval, SNS: Social Networking Sites

Introduction

Disasters are events which bring severe destruction to human lives and society [1].There are about thousands of disasters that have been recorded worldwide till date which has caused several human and economic losses [2]. Japan is one of the most disaster prone countries and is frequently hit by some natural disasters like earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, typhoons, heavy snow falls, torrential rains, floods and so on [3]. Due to the frequent occurrence of such disaster’s Japanese educational institutions, organizations and even the local communities organize several disaster drills and practice sessions in a regular time interval.

The Sendai framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 focuses on four priority areas which is “understanding the risk, strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk, investing in disaster reduction for resilience and enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response and to “Build Back Better” in recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction” [4]. All of these are essential to achieve sustainable reduction of disaster risk and reduce the detrimental effects of disasters among people and society. There are several disaster management policies in Japan and each prefectural government provides vast range of information on the disaster management, share guides on what should be done before, during and after certain disasters in multiple languages. However, Nepali language translation facilities are often not included in their websites [5]. Nepal is a country with almost similar landscapes to Japan hence is prone to almost similar kind of natural disasters. Each year many people lose their life or have to evacuate themselves from their home due to the effect of such disasters [6]. However, due to the unstable political situation of the country there are several challenges in incorporating the disaster preparedness knowledge and skills within the school health curriculums. Thus, the risk perception and emergency response towards the natural disasters like earthquakes, floods, etc. might be low among Nepalese population [7].

Nepalese students coming to Japan are mostly enrolled in the Japanese language institutions with limited number of students coming to Japan for higher studies. However, Japan is still one of the most preferred country of residence among Nepalese in Asia after India [8].The students coming to learn Japanese language can convey the skills among other Nepalese within their communities if trained well. Hence, identifying the knowledge and practice level among students is necessary in order to utilize their knowledge and skills later for information sharing and dissemination among Nepalese community in Japan. Thus, the objective of this study is to identify the level of knowledge, attitude and practice among Nepalese students residing in Japan regarding disaster preparedness and to identify factors associated with their disaster preparedness practice.

Methodology

A sub-sample was used from a cross-sectional study conducted among Nepalese immigrants residing in Japan including only those immigrants with their residency status as students and who were more than 18 years of age. A structured 63-itemed questionnaire was used for data collection. The information on questionnaire development and validation has been published elsewhere [7]. The information on knowledge of different types of natural disaster were collected in a five-point Likert scale from ‘very less knowledge’ to ‘very high knowledge’ using nine questions whereas attitude related nine questions were also presented in 5-point Likert scale ranging for ‘not concerned at all’ to ‘highly concerned’. This way the maximum score for the knowledge and attitude that one could gain was 40 and minimum was zero. Similarly, 10 questions related to the disaster preparedness practice like collection of necessary information regarding disaster management, evacuation center, evacuation route, etc. was collected using 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Do not want to do’ to ‘Have already done’. Here ‘Do not want to do’ was given a score of zero hence; the maximum score one could get for practice was also 40 with a minimum of zero.

The survey was collected using online software called ‘QuestionPro’ and online based written consent was obtained from all participants before the survey. Sample size included in the main paper was 404 however, we only included participants with their residency status as students hence, and our sample size was 96 for the logistic regression models. We performed bivariable logistic regression and multivariable logistic regression analysis to identify the factors associated with the knowledge, attitude and practice regarding disaster preparedness among students residing in Japan. The p-value of less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Stata version 16 was used for data coding and analysis.

Ethical approval

This is the secondary analysis done by using data collected from Nepalese immigrant population in a previous survey which obtained its ethical approval from the St. Luke’s International University Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Out of 404 respondents of the survey, nearly 24% (N = 96) had their residency status as students in Japan. The mean age of students was 26.51 ± 3.94 and about 65% were male. It was interesting to note that nearly 95% of the students were aware about natural disasters and about 29% had experienced some form of natural disasters during their stay in Japan. More than 60% of the students had completed their high school or less. Our study was dominated by respondents from Kanto area as majority of them were from this area. We also found that only 23% of the students were married. More than 55% of the participants didn’t identified Japanese language as a barrier for them. We also found that majority of students prefer Twitter (65.62%), Television (59.38%) and Newspaper (77.08%) as a source of information. However, only 18% of them identified the social networking site Facebook as a source of information collection. The preferred language for students was Nepali followed by English and Japanese. Meanwhile, the mean period of stay in Japan for students was 3.19 years. The mean score for attitude regarding disaster preparedness was higher (28.81 ± 6.13) compared to the mean knowledge score (22.63 ± 5.73) and mean practice score (16.04 ± 5.91) among students. (Table 1)

|

|

Student (N = 96) |

Non-student (N = 308) |

p-value |

|

Frequency (%) |

Frequency (%) |

||

|

Age, mean (SD) |

26.51 (3.94) |

38.32 (7.96) |

<0.001*** |

|

Aware about disaster |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

91 (94.79) |

293 (95.44) |

0.794 |

|

No |

5 (5.21) |

14 (4.56) |

|

|

Affected by disaster |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

28 (29.17) |

87 (28.25) |

0.862 |

|

No |

68 (70.83) |

221 (71.75) |

|

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

Male |

62 (64.58) |

191 (62.01) |

0.649 |

|

Female |

34 (35.42) |

117 (37.99) |

|

|

Education |

|

|

|

|

High school or less |

60 (62.50) |

195 (63.52) |

0.857 |

|

Bachelors and above |

36 (37.50) |

112 (36.48) |

|

|

Region of Japan |

|

|

|

|

Kanto area |

57 (59.38) |

205 (66.78) |

0.185 |

|

Others |

39 (40.62) |

102 (33.22) |

|

|

Marital status |

|

|

|

|

Single/ Divorced |

74 (77.08) |

33 (10.71) |

<0.001*** |

|

Married |

22 (22.92) |

275 (89.29) |

|

|

Language as a barrier |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

43 (44.79) |

131 (42.53) |

0.696 |

|

No |

53 (55.21) |

177 (57.47) |

|

|

Source of information a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

63 (65.62) |

198 (64.29) |

0.811 |

|

No |

33 (34.38) |

110 (35.71) |

|

|

Television |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

57 (59.38) |

198 (64.29) |

0.384 |

|

No |

39 (40.62) |

110 (35.71) |

|

|

Newspaper |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

74 (77.08) |

255 (82.79) |

0.209 |

|

No |

22 (22.92) |

53 (17.21) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

18 (18.75) |

56 (18.18) |

0.900 |

|

No |

78 (81.25) |

252 (81.82) |

|

|

Language preference |

|

|

|

|

English |

10 (10.42) |

22 (7.14) |

0.366 |

|

Nepali |

83 (86.46) |

281 (91.23) |

|

|

Japanese |

3 (3.12) |

5 (1.62) |

|

|

Period of stay, mean (SD) |

3.19 (2.16) |

7.66 (4.93) |

<0.001*** |

|

Practice of disaster preparedness, mean (SD) |

16.04 (5.91) |

15.80 (5.41) |

0.711 |

|

Knowledge of disaster preparedness, mean (SD) |

22.63 (5.73) |

20.89 (5.71) |

0.009** |

|

Attitude regarding disaster preparedness, mean (SD) |

28.81 (6.13) |

29.21 (5.75) |

0.556 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic distribution of students residing in Japan.

P-value obtained from chi-square test, **=p-value < 0.01, ***=p-value < 0.001, SD = Standard Deviation, a = results derived from multiple response question

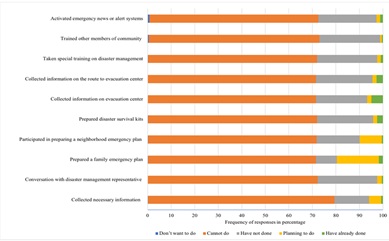

When we stratified the practice related questions regarding disaster preparedness, we found that majority of students were not able to collect necessary information related to disaster preparedness. More than 50% of them responded to ‘cannot do’ for most of the practice related questions like having conversation with the disaster management representative of their community, prepared family emergency plan, participated in the formation of neighborhood emergency plan, prepared disaster survival kits and so on. It was interesting to note that around (10-20)% of them were planning to participate in making the neighborhood emergency plan and family emergency plan. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Disaster preparedness practice among Nepalese students residing in Japan.

The multivariable linear regression analysis showed that knowledge regarding disaster preparedness and using smartphone as a source of information was associated with the disaster preparedness practice. With one unit increase in the knowledge score the practice of disaster preparedness increases by 22% [b = 0.219, SE = 0.109, 95% CI = (0.002 to 0.437)] after adjusting for all other covariates under analysis. Similarly, compared to those who do not use smartphone to collect information regarding disaster preparedness who uses it have 2.88 points [b = 2.877, SE = 1.249, 95% CI = (0.393 to 5.361)] higher disaster preparedness practice score. (Table 2).

|

|

Coefficient |

Robust SE |

95 % CI |

|

Knowledge score |

0.219 |

0.109 |

(0.002 to 0.437)* |

|

Attitude score |

0.120 |

0.098 |

(-0.075 to 0.315) |

|

Education |

|

|

|

|

High school or less |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Bachelors or higher |

0.953 |

1.394 |

(-1.819 to 3.724) |

|

Period of stay in Japan |

0.182 |

0.307 |

(-0.428 to 0.793) |

|

Source of information |

|

|

|

|

Smartphone |

|

|

|

|

No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Yes |

2.877 |

1.249 |

(0.393 to 5.361)* |

|

Television |

|

|

|

|

No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Yes |

1.771 |

1.330 |

(-0.872 to 4.415) |

|

Relatives |

|

|

|

|

No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Yes |

0.912 |

1.216 |

(-2.325 to 2.509) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Yes |

0.497 |

1.343 |

(-2.173 to 3.167) |

|

YouTube |

|

|

|

|

No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Yes |

0.865 |

1.446 |

(-2.010 to 3.741) |

Table 2: Multivariable linear regression model to identify factors associated with disaster preparedness practice among Nepalese students residing in Japan.

SE = Standard Error, CI = confidence interval, *= p-value < 0.05

Discussion

This study highlighted the perceived knowledge, attitude and practice regarding disaster preparedness among Nepalese students residing in Japan and showed that the Nepalese students in Japan have slightly higher level of knowledge and practice than the non-student group and there was a positive association between their knowledge and practice. Similarly, the use of smart phone to gather information regarding disaster preparedness was found to be significantly associated with the practice of disaster preparedness.

Students come to Japan mostly as a foreign language student followed by some students coming to Japan for their higher studies. Hence, students are supposed to have better language skills than other groups of population. However, they have to work 12-18 hours a day in order to earn their daily living in Japan [9]. Since the schools or universities are closed during the public holidays students naturally prefers to work during their holidays. In Japan, most of the disaster drills and practice sessions are organized during the public holidays. However, for students who works during their school holidays participation in such drills and practice sessions might not be feasible.

Furthermore, Nepal is a developing country with a very unstable political situation leading to several hindrances in the overall growth and development of the country [10]. Education and health sector are one of the areas where Nepal needs to meet many challenges in order to accomplish better health and education for all of its citizens [11]. Despite of the fact that there are several natural disasters that hit the country in a regular basis like landslides, floods, earthquakes, and etc. disaster preparedness is still not included in any of the schools’ or universities’ health curriculums [12]. The evidence showed by current study on student having just about average knowledge and practice skill on disaster preparedness might also be due to the fact that disaster management is not introduced to them during their schooling or university education.

This study showed that students can have increase in practice skills if they have higher knowledge which is also shown in several other studies conducted among various groups of population [13-15]. For students since they are young and active, they might be able to learn things quickly. Meanwhile, since the education system of Nepal encourages the use of English language more than their native language Nepali, many students might be able to assess health information from online media platforms or websites if they are provided information on government websites or media accounts that provides authentic information in English language as well. Hence, even if the prefectural government does not have much information in Nepali language, they can still understand the contents in English language. Similarly, there are several student peer support groups or consultation services which are available for students in Japan. If such groups could be utilized to provide information on disaster preparedness, many international students like Nepalese could benefit from it.

This study has explored the knowledge, attitude and practice among Nepalese residing in Japan however, the sample was drawn from an existing survey which used social media platforms to recruit their participants hence, there might be high possibilities that most of our respondents were actively involved in social activities. Similarly, we were not able to include non-social media users in this study. Having said that, this study provided an overview of disaster preparedness practice among Nepalese students and the inferences could be used to perform further large scale survey among similar population.

Conclusion

This study identified that Nepalese students residing in Japan had just about average knowledge and practice regarding disaster preparedness despite of the fact that majority of them are enrolled within a Japanese language institute or are working in Japan. This might suggest the ineffectiveness of disaster drills and practice sessions organized by the schools, communities or an organization in improving the knowledge, attitude and practice among Nepalese students. Hence, policies should be in place to make the disaster drills and practices mandatory for every newly admitted student within the language schools or even within the universities and increasing the stipend for working students might decrease the work-pressure for students so that they can focus on some health seeking behavior as well.

References

- What is a disaster? - IFRC.

- World Disasters Report 2014 - IFRC.

- White Paper on Disaster Management 2020(PDF): Disaster Management - Cabinet Office.

- Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 | PreventionWeb.net.

- Japan Links: Government & Politics:Local Governments: Prefectures.

- Rijal S, Adhikari S, Shrestha A (2020) Guiding Documents for Disaster Risk Reduction and Management in Health Care System of Nepal 58: 831-833.

- Bhandari AKC, Takahashi O (2022) Knowledge, attitude, practice and perceived barriers of natural disaster preparedness among Nepalese immigrants residing in Japan.

- Shakya P, Tanaka M, Shibanuma A, Jimba M (2018) Nepalese migrants in Japan: What is holding them back in getting access to healthcare?

- Shakya P, Sawada T, Zhang H, Kitajima T (2020) Factors associated with access to HIV testing among international students in Japanese language schools in Tokyo. PloS one.

- CD B (2022) Nepal’s political and economic transition report. Observational Research Foundation.

- Magar A (2013) Need of Medical Education System Reform in Nepal. Journal of the Nepal Medical Association 52: 1-2.

- Shiwaku K, Shaw R, Kandel R, Shrestha S, Dixit AM (2007) Future perspective of school disaster education in Nepal. Disaster Prevention and Management 16: 576-587.

- Xu D, Yong Z, Deng X, Liu Y, Huang K, et al. (2019) Financial Preparation, Disaster Experience, and Disaster Risk Perception of Rural Households in Earthquake-Stricken Areas Evidence from the Wenchuan and Lushan Earthquakes in China's Sichuan Province.

- Lin L, Ashkenazi I, Dorn BC, Savoia E (2014) The public health system response to the 2008 Sichuan province earthquake a literature review and interviews. Review 38: 753-773.

- Yousefi K, Larijani HA, Golitaleb M, Sahebi A (2019) Knowledge Attitude and Performance Associated with Disaster Preparedness in Iranian Nurses A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.

Citation: Aliza KCB, Takahashi O (2022) Disaster Preparedness among Nepalese Students Residing in Japan. J Community Med Public Health Care 9: 114.

Copyright: © 2022 Aliza K C Bhandari, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.