Do Sexually Abstinent Women have more Pelvic Floor Disorders? A Cross Sectional, Population Based Study

*Corresponding Author(s):

Rodrigo Guzman-RojasFacultad De Medicina, Clínica Alemana - Universidad Del Desarrollo, Santiago, Chile

Tel:+56 992403692,

Email:rodrigoguzman.66@gmasil.com

Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis: The aims were to establish the prevalence of sexually abstinent women because of Pelvic Floor Disorders (PFDs) in parous women, and to examine if abstinence was associated with symptoms of PFDs or functional anatomy of the pelvic floor.

Methods: Cross-sectional study of parous women responding to a questionnaire and undergoing pelvic floor examination. Distress for Urinary (UDI), Colorectal-Anal (CRADI), and Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POPDI) symptoms, Prevalence of Prolapse (POP-Q) ≥ grade 2, pelvic floor muscle injury on ultrasound and contraction (Modified Oxford Scale) were compared between sexually active women and abstinent women using Mann-Whitney U, logistic regression and Fisher’s exact tests.

Results: 1625 of 3115 women responded to the questionnaire, and 604 were examined. 1379 (85%) were sexually active, 22 (1.4%) were sexually abstinent because of PFDs and 224 (14%) for other reasons. Abstinent women because of PFDs had higher mean (SD) symptom scores [UDI 38.8 (16.8), CRADI 36.6 (21.8), POPDI 10.9 (10.4)] than sexually active women [UDI 9.8 (14.1), CRADI 11.1 (14.4), POPDI 2.3(5.5)] p0.05.

Conclusion: Symptoms of PFDs were more important than objective measures of prolapse, muscle injury and contraction for sexual activity in parous women.

Keywords

Fecal incontinence; Levator ani muscle trauma; Pelvic floor disorders; Pelvic organ prolapse; Sexual activity; Urinary incontinence

Brief Summary

Only 1-2% of parous women avoid sex because of pelvic floor disorders. Sexual abstinence is not associated to anatomical prolapse, muscle injury and contractility.

Introduction

Pelvic Floor Disorders (PFDs) such as Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP), urinary and anal incontinence are common disorders among parous women [1,2]. Conflicting evidence has been published on the effect of PFDs on sexual function and activity [3-10]. Urinary incontinence and body image consistently appear to play an important role for sexual dysfunction in women with PFDs [10,11-13]. Increasing age and menopause will also contribute to decreased sexual activity [3,9,14]. The prevalence of sexual abstinence because of symptomatic PFDs has been poorly studied in the general population [9,14]. Among female patients with urinary incontinence, avoidance of intercourse has been reported in 20-36% and in up to 73% of women planned for POP surgery [8,15]. We found no population based studies examining the association between sexual activity and POP verified at clinical examination. A strong pelvic floor has been associated with higher rates of sexual activity, and for patients, improvement of sexual function after pelvic floor muscle training has been reported [16,17]. One study has reported poor sexual function several years after obstetric anal sphincter tears, indicating a possible link to trauma occurring during vaginal delivery [18]. The association of injury to the levator ani muscle with sexual activity has only been studied few months after childbirth [19,20].

The aim of this study was to establish the prevalence of sexual abstinence because of PFDs among women 20 years after first delivery, and to study the association between sexual abstinence and symptoms of PFDs and objective measures of prolapse, pelvic floor muscle trauma and - contraction.

Materials And Methods

The present study was part of a cross-sectional study among 3115 women who delivered their first child at Trondheim University Hospital between 1 January 1990 and 31 December 1997. A large proportion of women with operative deliveries were included, because the study was designed to compare the prevalence of PFDs and muscle trauma after different modes of delivery [21,22]. Exclusion criteria were stillbirth, breech delivery and infant birth weight < 2000g at first delivery, but women were not excluded if these conditions occurred in subsequent pregnancies. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Because of a lack of similar studies in women from a normal population, no power calculation was performed. Sample size calculations were based on the main outcome (difference in levator ani muscle trauma between different modes of delivery) for a previously published study [21].

A postal questionnaire regarding symptoms of PFDs was sent in March 2013, with two reminders to non-responders. Women were asked to state whether they were sexually active or not. Three responses were possible: 1) Yes, 2) No, because of pelvic floor symptoms (prolapse, leakage of urine or feces) and 3) No, for other reasons. No further details regarding sexuality were investigated. Women were divided in three study groups based on their response. The questionnaire contained a Norwegian translation of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory to measure women’s bother with symptoms from prolapse, the lower urinary and the lower gastrointestinal tract [23]. Symptomatic PFDs were defined by either a positive response to the question regarding seeing/ feeling a vaginal bulge, urinary incontinence (at urgency and/ or coughing, laughing, sneezing) or fecal incontinence (loose and/ or formed stool). The proportion of women in each of the three groups experiencing symptoms of none, one, two and three PFDs was calculated. Then a symptom score was calculated for each of the subscales of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory: Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress (POPDI), Urinary Distress (UDI) and Colorectal-Anal Distress (CRADI), range 0-100. Higher scores indicated more bother or distress. The questionnaire also provided information about Body Mass Index (BMI) and menopause. Menopause was correlated to age and few women answered to the question about hormone replacement therapy, so this was not included in the analyses. Information about parity was verified with the Medical Birth Registry of Norway.

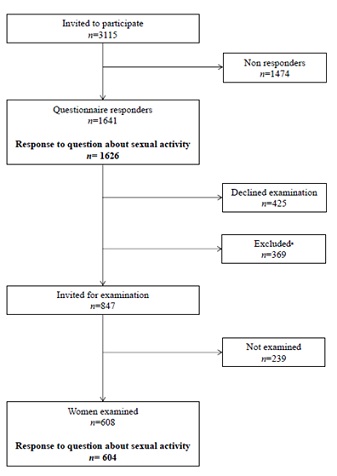

A selection of questionnaire responders, from both rural and urban areas living in and around Trondheim in 2013,were invited for clinical examination, regardless of symptoms indicated on the questionnaire, see figure 1 and [21] for details. Women were examined in the supine position after bladder and bowel emptying, with the hips and knees semi-flexed, and the lower abdomen covered up to hide any surgical scars. The examiner (IV) was blinded to all background characteristics, obstetric history, sexual activity and symptoms regarding PFDs. Prolapse was quantified according to the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system, providing staging of POP: Stage 0 (no POP), stage 1 (most distal part of POP>1 cm above the hymen), stage 2 (most distal part of POP≤ 1 cm above or below the hymen), stage 3 (most distal part >1 cm below the hymen) and stage 4 (complete eversion of vagina and uterus) [24]. A POP ≥stage 2 in any compartment (anterior, middle, posterior) was regarded as clinically relevant. Pelvic floor muscle contraction was assessed by palpation and perineometry. First, the examiner inserted the middle and index finger approximately 4 cm into the vagina using the Modified Oxford Scale to rate pelvic floor muscle contraction from 0-5. Zero corresponds to no contraction and 5 to a strong contraction [25]. The woman was asked to perform three maximum pelvic floor contractions, and the average was used for analyses. Then the maximal vaginal squeeze pressure was measured (in cm H2O) by inserting a vaginal balloon catheter (CamthecAS, Sandvika, Norway) approximately 3.5 cm inside the introitus [26]. Ultrasound examination of pelvic floor muscles was performed with a GE Voluson S6 device using the RAB 4-8MHz abdominal Three-Dimensional (3D) probe with an acquisition angle of 85° applied to the perineum and introitus of the woman.

Figure 1: Flow chart of study participants.

Figure 1: Flow chart of study participants.

aExclusion criteria were living too far from Trondheim in 2013 and vaginal delivery after caesarean delivery, forceps after vacuum, vacuum after forceps and vacuum or forceps after normal vaginal delivery as described previously [21].

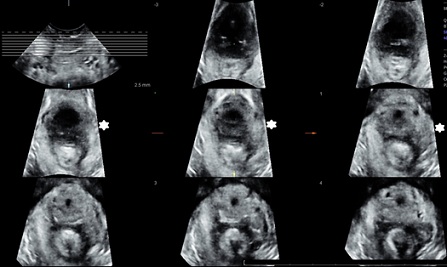

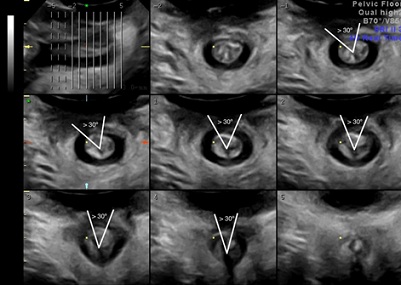

Offline analysis of the 3D/4D ultrasound volumes was performed 6-30 months after the ultrasound scan on a computer using the 4Dview Version 14 Ext.0 software (GE Healthcare, Austria). Two authors (IV and RGR) performed the analyses blinded to all other study data. Muscle trauma was assessed with tomographic ultrasound imaging .We defined significant levator ani muscle trauma (examined by IV) when all three central slices; in the plane of minimal hiatal distensions and 2.5-5.0 mm cranial to this, showed an abnormal insertion of the most medial fibers of the levator ani muscle to the pubic bone at muscle contraction, either uni- or bilateral, figure 2 [27]. Anal sphincters were examined (by RGR), and a significant defect was defined if four out of six slices on tomographic ultrasound imaging showed a defect of ≥30° in the external and/ or internal anal sphincters, figure 3 [28].

Figure 2: Left-sided levator muscle injury in all three central planes on tomographic ultrasound imaging indicated with *.

Figure 2: Left-sided levator muscle injury in all three central planes on tomographic ultrasound imaging indicated with *.

Figure 3: External anal sphincter defect of ≥ 30o in ≥4/6 planes on tomographic ultrasound imaging.

Figure 3: External anal sphincter defect of ≥ 30o in ≥4/6 planes on tomographic ultrasound imaging.

The study was approved in March 2012 by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK midt 2012/666) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with identifier NCT01766193.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS statistics version 23 software (Armonk, NY, USA), and a two-sided p- value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were tested for normal distribution. Differences in background characteristics were calculated between women in the three study groups, using independent group t-test. Data from the symptom scores, perineometry and Modified Oxford Scale were not normally distributed, and Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate differences in scores between women from the three study groups. This test does not permit correction for potential confounders, therefore we performed a separate correlation analysis for age, BMI and parity, against each symptom score and found no (age and parity) or negligible (BMI) correlation.

Logistic regression was used to examine the association between sexual activity and the presence of each PFD. Age, BMI and parity were entered in a multiple regression model for calculation of Adjusted Odds Ratios (aOR) with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) between groups. The Fisher’s exact test (http://www.r-fiddle.org/#/) was used to calculate Crude Odds Ratios (cOR) when comparing POP grade ≥ 2 and muscle trauma between the groups, because of few women in the sexual abstinent group. Missing items were dealt with by using the mean from answered items to calculate the UDI, CRADI and POPDI scores [23]. Other missing data were dealt with by omitting analysis on women with no data for the variable.

Results

A total of 1625 (52%) women responded to the question about sexual activity, and 604 of them were examined, see figure 1. Background characteristics for the whole study population and the three study groups are presented in table 1. Only 22 of 1626 women (1.4 %) avoided sex because of PFDs. Furthermore, 224 (13.8%) women were not sexually active for other, non-specified reasons. Most women 1379 (84.8%) were sexually active. Women not sexually active because of PFDs were significantly older and had lower parity and higher BMI than sexually active women, and they had a higher BMI than sexually abstinent women for other reasons. A POP ≥ grade 2 was found in 274 (45%) of the 604 women examined, and a prolapse grade 3 in 11 (2%) women. In total 113(19%) women were diagnosed with significant levator muscle injury and 86 (14%) had significant anal sphincter defect.

|

|

Total

N= 1641 |

I because of PFDs N=22 |

II Sexually active N=1379 |

III Sexually abstinent for other reason N=224 |

I versus II |

I versus III |

||||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

t-test, p |

|

|

Age years

|

47.3 |

4.9 |

50.6 |

5.0 |

46.8 |

4.5 |

49.8 |

5.8 |

<0.01 |

0.53 |

|

BMI kg/m2

|

25.8 |

4.7 |

28.7 |

5.6 |

25.7 |

4.6 |

26.3 |

4.9 |

<0.01 |

0.03 |

|

Parity number

|

2.2 |

0.8 |

1.7 |

0.8 |

2.3 |

0.8 |

1.9 |

0.8 |

<0.01 |

0.14 |

Table 1: Background characteristics of study participants. Pelvic Floor Disorders (PFDs).

The proportion of women reporting each PFD and more than one type of PFDs was higher in the group avoiding sex because of PFDs, see table 2. Sexually abstinent women because of PFDs had significantly higher symptom scores for all PFDs than sexually active women and women abstinent for other reasons. Women not sexually active for other reasons had symptoms similar with sexually active women. Symptoms of urinary and fecal incontinence were more frequent, and women experienced more distress related to incontinence symptoms than POP in all study groups. Correction for confounders did not change the results. We found no significant difference in prevalence of POP ≥ grade 2 or levator and anal sphincter muscle injury between women sexually abstinent because of PFDs and the other groups, and pelvic floor muscle contraction was similar between the different groups, table 3. Of the 11 women with prolapse grade three, only one avoided sex because of PFDs.

|

I Sexually abstinent because of PFDs |

II Sexually active |

III Sexually abstinent for other reasons |

I versus II |

I versus III |

||||||||

|

Symptom present |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

aOR |

95% CI, p |

aOR |

95% CI, p |

||

|

Urinary incontinence N= 21, 1372, 219 |

20 |

95.2 |

598 |

43.6 |

127 |

58.0 |

26.1a |

3.4-197.9, <0.01 |

13.5a |

1.8-103.3, 0.01 |

||

|

Fecal incontinence N=21, 1376, 221 |

8 |

38.1 |

108 |

7.8 |

28 |

12.7 |

5.8 |

2.3-14.5, <0.01 |

3.8 |

1.4-10.0, <0.01 |

||

|

Pelvic organ prolapse N=20, 1366, 222 |

5 |

25.0 |

122 |

8.9 |

22 |

9.9 |

3.6 |

1.2-10.3, <0.01 |

3.0 |

1.0-9.3, 0.05 |

||

|

>1 pelvic floor disorderb N= 20, 1357, 218 |

11 |

55.0 |

132 |

9.7 |

37 |

17.0 |

10.9 |

4.3-27.6, <0.01 |

5.4 |

2.1-14.2, <0.01 |

||

|

Symptom score |

Mean, Median |

SD, range |

Mean, Median |

SD, range |

Mean, Median |

SD, range |

Mann-Whitney U test, p |

|||||

|

UDI N=21,1378,221 |

38.8 40.0 |

16.8 12.5-75.0 |

9.8 4.2 |

14.0 0-75.0 |

12.6 8.3 |

14.1 0.0-58.3 |

|

<0.01

|

|

<0.01

|

||

|

CRADI N=21,1376, 221 |

36.6 37.5 |

21.8 0.0-83.0 |

11.1 6.3 |

14.4 0.0-100 |

12.8 7.2 |

14.5 0.0-71.9 |

|

<0.01

|

|

<0.01

|

||

|

POPDI N=21, 1379, 223 |

10.9 6.0 |

10.4 0.0-35.0 |

2.3 0.0 |

5.5 0.0-95.8 |

3.2 2.0 |

6.5 0.0-66.7 |

|

<0.01

|

|

<0.01

|

||

Table 2: Symptoms of Pelvic Floor Disorders (PFDs) and distress with these symptoms according to study groups. Multiple logistic regression with Adjusted Odds Ratios (aOR) and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) and Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups. UDI, Urinary Distress Inventory; CRADI, Colo-Rectal Anal Distress Inventory; POPDI, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory.

aParity (1.2, 95% CI;1.0-1.4), p=<0.01) and BMI (1.1, 95% CI;1.1-1.1) p=<0.01) were significant confounders for urinary incontinence. b Proportion calculated from women that responded to all three questions.

|

I Sexually abstinent because of PFDs |

II Sexually active |

III Sexually abstinent for other reasons |

I versus II |

I versus III |

||||||

|

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

cOR |

95% CI, p |

cOR |

95% CI, p |

|

Pelvic organ prolapse ≥ grade 2, N=9, 499, 96 |

4 |

44.4 |

235 |

47.1 |

35 |

36.5 |

0.9 |

0.2-3.4, 1.00 |

1.2

|

0.3-4.7, 0.75 |

|

Levator muscle injurya N= 9, 497, 96 |

2 |

22.2 |

94 |

18.9 |

17 |

17.7 |

1.6 |

0.3-6.7, 0.44 |

1.5

|

0.2-6.7, 0.70 |

|

Anal sphincter defecta N= 9, 463, 89 |

3 |

33.3 |

72 |

15.6 |

11 |

11.2 |

2.7 |

0.4-13.0, 0.16 |

3.5

|

0.5-19.4, 0.12 |

|

|

Mean Median |

SD Range |

Mean Median |

SD Range |

Mean Median |

SD Range |

Mann-Whitney U test, p |

|||

|

Modified Oxford Scale N= 9, 499, 96 |

3.1 3.0 |

1.3 0-5 |

3.1 3.0 |

1.3 0-5 |

3.1 3.0 |

1.2 0-5 |

|

0.41 |

|

0.41 |

|

Perineometry, cm H2Oa N= 6, 465, 85 |

34.7 33.0

|

20.2 12.0-67

|

29.7 25.0

|

19.8 0-129

|

29.1 24.0

|

19.6 2-102

|

|

0.45 |

|

0.38 |

Table 3: Findings at examination: pelvic organ prolapse ≥ grade 2, levator muscle injury, anal sphincter defect, modified Oxford Scale and perineometry for each study group. Fisher’s exact test with Crude Odds Ratios (cOR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) and Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups. Pelvic Floor Disorders (PFDs).

aFor assessment of levator injury and anal sphincter defects a total of 602 and 561 volumes were available respectively, and a total of 556 women were examined with perineometry.

Discussion

In this study, we found that only one to two percent of parous women from a general population avoided sex because of symptoms of PFDs. As expected, these women had significantly higher prevalence and distress scores related to prolapse, urinary, and colorectal-anal symptoms than sexually active women. On the other hand, no difference in prevalence of pelvic floor muscle trauma and contractility or prolapse at examination was found. This may implicate that objective measure of POP and presence of muscle trauma is not a common reason to avoid sexual activity. Distress with subjective experience of prolapse and incontinence symptoms seems to be more important for sexual dysfunction. This finding is consistent with previous studies in patient populations, describing no correlation between vaginal topography and sexual function [12,29]. This highlights the importance of doctors asking women who present with symptoms of PFDs about sexual problems, regardless of anatomic findings. Previous studies have found that a large proportion of women scheduled for prolapse surgery have sexual dysfunction, and that sexual function was improved after surgery [13,30]. In the present study, only 11 women had prolapse stage three, and it is possible that a larger prolapse may have more impact on sexual function. High parity is an established risk factor for PFDs [1,2]. In this study, we found that sexually abstinent women because of PFDs had lower parity, implicating that higher parity does not have a negative impact on sexual activity later in life, which is consistent with results from a previous study [31].

Strengths of the present study were that participants were recruited from a general population of parous women in contrast to patient populations used in previous studies, and the large sample size. They answered a standardized questionnaire about PFDs. In addition, a representative proportion of included women were examined, with quantification of prolapse, muscle trauma and pelvic floor muscle contraction, and therefore many variables regarding pelvic floor anatomy and function were analyzed in relation to sexual activity. We found no previous studies investigating the association between sexual activity, PFDs and pelvic floor anatomy in women from a general population.

Limitations of the study were that study participants were asked only one question regarding sexual activity, and we lack information about libido, arousal, orgasm, pain and other conditions related to sexual function. No question regarding leakage of urine, gas or stool during sexual activity was included in the questionnaire. Another weakness is the lack of information about why some women were not sexually active for “other reasons”. Absences of partner, partner disinterest and physical problems have been reported as common reasons [5]. Physical problems and disinterest of the women could be other reasons. The moderate response rate of 52% could have introduced a bias including women with higher symptom scores, as symptomatic women are more prone to respond to questionnaires. No objective tests of leakage, such as pad weighing test or leakage diary were performed. This was a cross-sectional study which allows us to study associations and not causality between sexual activity, PFDs and pelvic floor anatomy. As most women of the study population were Caucasians, the results may not be applicable to other ethnic groups.

Two previous studies with a short follow up after delivery have published results regarding levator muscle trauma and sexual function [19,20]. They found increased vaginal laxity and reduced vaginal sensation in women with levator injury. In the present study, no clear association between muscle injury and sexual function was found. There is a possibility that the long-term effect of levator trauma on sexual function can be different to a short-term effect. Dyspareunia could be associated with muscle injury, and this symptom was not investigated in our study. We observed a higher proportion of anal sphincter defects in women who were not sexually active because of PFDs, but this group was small (n=9), and there was insufficient statistical power to verify a statistically significant difference compared to sexually active women. In a study of women five years after obstetric anal sphincter tears most women had sexual dysfunction, and this was more pronounced in women with larger tears [18]. Women without tears were not included.

Kanter et al., found that a strong pelvic floor was associated with higher rates of sexual activity in women with PFDs [17]. We found no association between muscle contraction and sexual activity. Brækken et al., have demonstrated that pelvic floor muscle training can improve sexual function in women with POP [16]. In the current study women were examined once, without possibility to detect a possible effect of pelvic floor muscle exercise on sexual activity over time. It is possible that the proportion of women avoiding sex because of PFDs increases with advancing age. Muscle trauma occurring during vaginal delivery and particularly forceps delivery, could have impact on women’s sexual activity after a longer interval than 20 years. A follow up study of the women 10-15 years from now could help to establish whether women with injured or weaker pelvic floor muscles and anatomical prolapse will develop more sexual dysfunction over time.

In conclusion, it was uncommon among parous women from the normal population to avoid sex because of symptoms of pelvic floor disorders. Women avoiding sex because of prolapse and incontinence symptoms experienced more distress related to their pelvic floor disorders than sexually active women. No difference in prevalence of pelvic floor muscle trauma, contractility and prolapse was found at examination between women avoiding sex and sexually active women, implicating that symptoms are more important than objective anatomical findings for sexual activity in women from a general population.

Conflicts of Interest Notification

All authors declare no potential financial or personal conflicts of interest.

Author’s Participation in the Manuscript

I Volløyhaug: Protocol development, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing

R Lonnee-Hoffmann: Data analysis, manuscript writing

R Guzman-Rojas: Data analysis, manuscript writing

KÅ Salvesen: Protocol development, data analysis, manuscript writing

Acknowledgment

We thank Christine Østerlie and Tuva K. Halle for help with identifying potential study participants and Guri Kolberg for help with coordination of clinical examinations. We thank Øyvind Salvesen for advice on statistical analyses.

Funding

The study was financially supported by the Norwegian Women’s Public Health Association/the Norwegian Extra Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation through EXTRA funds, Trondheim University Hospital, Norway and by Desarrollo médico, Clínica Alemana de Santiago. The funders played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in the writing of the report and decision to submit the article for publication. All researchers were independent from funders.

References

- Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, et al. (2008) Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA 300: 1311-1316.

- Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, Redden DT, Burgio KL, et al. (2014) Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women. Obstet Gynecol 123: 141-148.

- Weber AM, Walters MD, Schover LR, Mitchinson A (1995) Sexual function in women with uterovaginal prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 85: 483-487.

- Fashokun TB, Harvie HS, Schimpf MO, Olivera CK, Epstein LB, et al. (2013) Sexual activity and function in women with and without pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J 24: 91-97.

- Rogers GR, Villarreal A, Kammerer-Doak D, Qualls C (2001) Sexual function in women with and without urinary incontinence and/or pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 12: 361-365.

- Espuña Pons M (2009) Sexual health in women with pelvic floor disorders: Measuring the sexual activity and function with questionnaires--a summary. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 1: 65-71.

- Pauls RN, Segal JL, Silva WA, Kleeman SD, Karram MM (2006) Sexual function in patients presenting to a urogynecology practice. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 17: 576-580.

- Barber MD, Visco AG, Wyman JF, Fantl JA, Bump RC, et al. (2002) Sexual function in women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 99: 281-289.

- Lukacz ES, Whitcomb EL, Lawrence JM, Nager CW, Contreras R, et al. (2007) Are sexual activity and satisfaction affected by pelvic floor disorders? Analysis of a community-based survey. Am J Obstet Gynecol 197: 88.

- Nilsson M, Lalos O, Lindkvist H, Lalos A (2011) How do urinary incontinence and urgency affect women's sexual life? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 90: 621-628.

- Roos AM, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Burger CW, Paulus AT (2014) Pelvic floor dysfunction: women's sexual concerns unraveled. J Sex Med 11: 743-752.

- Lowenstein L, Gamble T, Sanses TV, van Raalte H, Carberry C, et al. (2009) Sexual function is related to body image perception in women with pelvic organ prolapse. J Sex Med 6: 2286-2291.

- Lonnée-Hoffmann RA, Salvesen Ø, Mørkved S, Schei B (2013) What predicts improvement of sexual function after pelvic floor surgery? A follow-up study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 92: 1304-1312.

- Addis IB, Van Den Eeden SK, Wassel-Fyr CL, Vittinghoff E, Brown JS, et al. (2006) Sexual activity and function in middle-aged and older women. Obstet Gynecol 107: 755-764.

- Jha S, Gopinath D (2016) Prolapse or incontinence: What affects sexual function the most? Int Urogynecol J 27: 607-611.

- Braekken IH, Majida M, Ellström Engh M, Bø K (2015) Can pelvic floor muscle training improve sexual function in women with pelvic organ prolapse? A randomized controlled trial. J Sex Med 12: 470-480.

- Kanter G, Rogers RG, Pauls RN, Kammerer-Doak D, Thakar R (2015) A strong pelvic floor is associated with higher rates of sexual activity in women with pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J 26: 991-996.

- Visscher AP, Lam TJ, Hart N, Felt-Bersma RJ (2014) Fecal incontinence, sexual complaints, and anorectal function after third-degree Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injury (OASI): 5-year follow-up. Int Urogynecol J 25: 607-613.

- van Delft K, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Schwertner-Tiepelmann N, Kluivers K (2014) The relationship between postpartum levator ani muscle avulsion and signs and symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction. BJOG 121: 1164-1171.

- Thibault-Gagnon S, Yusuf S, Langer S, Wong V, Shek KL, et al. (2014) Do women notice the impact of childbirth-related levator trauma on pelvic floor and sexual function? Results of an observational ultrasound study. Int Urogynecol J 25: 1389-1398.

- Volløyhaug I, Mørkved S, Salvesen Ø, Salvesen KÅ (2015) Forceps delivery is associated with increased risk of pelvic organ prolapse and muscle trauma: A cross-sectional study 16-24 years after first delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 46: 487-495.

- Volløyhaug I, Mørkved S, Salvesen Ø, Salvesen K (2015) Pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence 15-23 years after first delivery: A cross-sectional study. BJOG 122: 964-971.

- Barber MD, Walters MD, Bump RC (2005) Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am J Obstet Gynecol 193: 103-113.

- Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, et al. (1996) The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 175: 10-17.

- Laycock J (1994) Pelvic muscle exercises: Physiotherapy for the pelvic floor. Urol Nurs 14: 136-140.

- Kegel AH (1948) Progressive resistance exercise in the functional restoration of the perineal muscles. Am J Obstet Gynecol 56: 238-248.

- Dietz HP, Bernardo MJ, Kirby A, Shek KL (2011) Minimal criteria for the diagnosis of avulsion of the puborectalis muscle by tomographic ultrasound. Int Urogynecol J 22: 699-704.

- Guzmán Rojas RA, Shek KL, Langer SM, Dietz HP (2013) Prevalence of anal sphincter injury in primiparous women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 42: 461-466.

- Edenfield AL, Levin PJ, Dieter AA, Amundsen CL, Siddiqui NY (2015) Sexual activity and vaginal topography in women with symptomatic pelvic floor disorders. J Sex Med 12: 416-423.

- Glavind K, Larsen T, Lindquist AS (2015) Sexual function in women before and after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 94: 80-85.

- Fehniger JE, Brown JS, Creasman JM, Van Den Eeden SK, Thom DH, et al. (2013) Childbirth and female sexual function later in life. Obstet Gynecol 122: 988-997.

Citation: Volløyhaug I, Lonnee-Hoffmann RAM, Salvesen KÅ, Guzman-Rojas R (2022) Do Sexually Abstinent Women have more Pelvic Floor Disorders? A Cross Sectional, Population Based Study. J Reprod Med Gynecol Obstet 7: 0104.

Copyright: © 2022 Ingrid Volløyhaug, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.