Does Social Participation Modify the Association between Depression and Cognitive Functioning among Older Adults in China? A Secondary Analysis based on CHARLS

*Corresponding Author(s):

Xinyue MaTeachers College, Columbia University, New York, United States

Tel:+1 0019178474582,

Email:xm2289@tc.columbia.edu

Lingyun Ran

Nursing School Of Kunming Medical University, Kunming, Yunnan, China

Tel:+86 15812030739,

Email:ranlingyun@kmmu.edu.cn

Abstract

Background: Cognitive impairment and depression significantly affect the mental health of older Chinese adults. While previous studies highlighted the positive impact of social participation on cognitive functioning and depression, research on its specific types and their influence on the depression-cognitive relationship is limited. This study investigated which social activities mitigate cognitive impairment and if they moderate depression's effect on cognitive functioning in older Chinese adults.

Methods: The study conducted hierarchical regression analysis on the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) dataset of 5,056 older adults. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was employed to measure the cognitive performance of the subjects, and the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) was utilized to evaluate depressive symptoms. Hierarchical regression analysis tested the fit of step-wise models: Model 1 examined the main effect of depression on cognitive functioning; Model 2 & 3 assessed the main and interactive effects of formal and informal social participation; and Model 4 & 5 evaluated the effects of specific social participation categories and their interactions with depression on cognitive functioning.

Results: Regression results indicated that depression significantly impacted older Chinese adults’ cognitive functioning in all models. Engaging in both formal and informal social activities reduced cognitive decline among these adults. Specific activities like “playing mahjong, chess, or cards,” “attending clubs or community organizations” and “stock investing” positively correlated with the MMSE scores. No interaction was observed between any form of social participation and depression.

Conclusion: The study highlighted the positive impact of social participation, especially informal activities, on the mental health of older Chinese adults. Its findings have implications for public policy and health, suggesting the need for social venues and activities for older adults. This could enhance their life satisfaction and ease the load on China’s health system.

Keywords

Cognitive functioning; Depression; Older adults in China; Social activity; Social participation

Background

Population aging has become one of the most pressing social issues in modern China since the aging population in China is increasing at an unprecedented rate [1]. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China [2], the proportion of older adults in China reached 18.7% in 2020, which were more than 260 million people [2]. The proportion of older adults in China has been rapidly increasing due to declining fertility rates and increasing life expectancy [3]. This demographic shift has significant implications for health and social care systems, particularly in relation to cognitive impairment and depression among older adults [3,4].

Cognitive impairment is a prevalent problem among older Chinese adults. According to Xue’s research, the incidence of cognitive impairment among older adults in China is about 14.61% in nonclinical samples [4]. This is a major public health concern since cognitive impairment can result in disability, decreased quality of life, and increased healthcare expenses [1]. Cognitive maintenance has important implications in sustaining the life quality and well-being of older adults [5]. Moreover, impairment in cognitive ability carries risks for severe loss of cognitive functioning such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease [6-8]. Studies have shown that demographic factors contributing to cognitive functioning include gender, age, education, living style and many other aspects [8-14]. Supported by previous studies, Zhang and colleagues [9] found that higher odds for cognitive impairment is significantly associated with female, older age, lower education level, living alone with no spousal support, less income, worse psychological well-being, less fresh fruit and vegetable intake, lower social engagement, and more activities of daily living limitations [15-17].

Depression is another widespread ailment among older adults in China [18]. A study in 2022 showed that an estimated 33% and above of older adults in China demonstrated depressive symptoms [19]. Depression can have a substantial impact on older adults’ quality of life, resulting in diminished independence, social isolation and functioning in everyday tasks [18,20,21]. Zhou and colleagues [22] discovered a negative correlation between depressive symptoms and cognitive functioning among older Chinese adults using The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHRLS). Older adults who scored higher on the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) were more likely to exhibit suboptimal cognitive functioning, scoring lower in the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in aspects such as orientation, memory, and attention and computation.

Social participation requires older adults to engage in several important mental processes. Previous studies [23] showed that social activities such as playing mahjong or card games reinforce short-term episodic memory. It indicates that enhancing mental processes may help bolster cognitive functioning among older adults. Moreover, social participation may influence depressive symptoms [24-26]. Participating in social activities could reduce depressive symptoms in older adults by providing social support, a sense of purpose and increased physical activity [27]. According to previous studies, depression has been linked to cognitive impairments such as memory problems and slower processing speed [28,29]. Furthermore, prior studies demonstrated that social participation could be a protective factor against cognitive decline by reducing the risk of developing depression [30,31]. Based on those findings, it is reasonable to speculate that it may mitigate the negative effects of depression on cognitive functioning.

The activities involved in social participation can be divided into formal and informal categories, depending on the degree of intimacy and intensity [32]. According to a study conducted based on the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA), informal activities involve interaction with family, friends, and neighbors, while formal activities involve participating in formal organizations such as alumni societies [33]. Researchers found that both formal and informal activities can reduce depression and improve cognitive functioning in older adults [33,34]. However, participating in which types of social activities can protect cognitive functioning from depression remains unclear.

Several studies in the past examined the relationship between social participation, depression, and cognitive functioning [35,36]. Some researchers have suggested that certain types of activities, such as physical exercise, may have a greater impact on cognitive functioning and depression [22,35,37]. Despite the promising implications of social participation, few studies have explored the influence of specific types of social activities. Thus, this study aims to examine 1) whether social participation serves as a preventative measure and mitigates the negative impacts on cognitive functioning in the older Chinese adult population; 2) which type(s) of social activities (i.e., formal or informal) could benefit older Chinese adults' cognitive functioning; 3) whether the interaction between social participation and depression influences cognitive functioning.

Methods

- Sample selection

- Database

The dataset used is the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), which collected data from socioeconomic status to health conditions for a nationally representative sample of Chinese residents aged 45 and older. However, individuals over the age of 45 comprise a wide range of age groups, from middle-aged (48 to 64 years) to oldest-old (≥85 years) categories [38,39]. Besides, the Law of the People's Republic of China on the Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly, promulgated in 1996, defines a senior as 60 years and above [40]. The study population in this study was therefore restricted to over-60-year-olds.

The CHARLS utilized a probability-proportional-to-size sampling method [41]. The sample comprised all country-level units (excluding Tibet) and was stratified based on regional, county-level (urban/rural) and per-capita GDP characteristics. Participants were followed up every 2 or 3 years over four waves since 2008 [41]. In this study, we chose to use the most recent wave (Wave 4) which was conducted between July 2018 and March 2019 [40]. We obtained the data of Wave 4 on November 25 after submitting our application to the CHARLS database on November 17, 2022 [42].

- Inclusion criteria

There are 19,816 respondents in the current dataset. Our study included older adults based on three criteria: 1) their age was 60 years and above; 2) they completed basic demographic information including age, gender, education level, marital status, and location of residential address; 3) they answered all questions in both the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10). Finally, a total of 5,056 older adults were included.

- Variable selection

- Outcome variable

Cognitive Functioning: The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is an 11-item, 30-point questionnaire first developed by Folstein to measure cognitive performance [43,44]. It is now widely used as a measure to assess older adults’ cognitive functioning in research environments and performed in a systematic and routine manner as a screening tool in clinical and community settings to identify cognitive impairment in older, community-dwelling, hospitalized, and institutionalized adults [45]. The CHARLS dataset used the Chinese version of the MMSE, which shows good validity and reliability (Cronbach's α=0.86) [46-48]. In this study, Cronbach's α coefficient was .75.

These items consist of eight cognitive domain functions: orientation [e.g., “What is the year?” “What is the season of the year?”], registration [e.g., “I am going to name three objects. After I have said them, I want you to repeat them. Remember what they are because I am going to ask you to name them again in a few minutes. Ball, flag, tree. Please repeat the names for me.”], attention and calculation [e.g., “Please calculate 100 minus 7, and keep minus 7 continuously, tell me each answer you get from minus 7, until I say stop.”], recall and delayed recall [e.g., “What were the three objects I asked you to remember?”], naming [e.g., Showing the respondent the watch picture on the screen and asking, “What is this called?”], repetition [e.g., “I would like you to repeat a phrase after me. The phrase is: ‘No if’s and’s or but’s’”], verbal and written comprehension [e.g., “Write any complete sentence on that piece of paper for me.”], and visuospatial capability [e.g., “I am going to give you a piece of paper. When I do, take the paper in your right hand, fold the paper in half with both hands, and put the paper down on your left lap.”] [48]. Each correct answer scores 1 point for the respondent. The normal level is a score of 24 or higher (out of 30). Scores of 23 or lower suggest a cognitive impairment that is either severe (9 points), moderate (10–18 points), or mild (19–23 points).

- Explanatory variables

Depressive Symptoms: Depressive symptoms were measured with the Chinese version of the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10).Andresen and his colleagues invented CESD-10 in 1994, a now widely used measure to screen for depression in primary care settings [49]. It is a Likert scale survey assessing depressive symptoms in the past week, which shows good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.96) [50]. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this study was .80, showing good consistency.

CESD-10 consists of 10 items, which include three items on depressed affect [i.e., 1-“I was bothered by things that usually don't bother me”; 3-” I felt depressed”; 4-” I felt that everything I did was an effort”], five on somatic symptoms [i.e., 2 -” I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing”; 6-“ I felt fearful”; 7-“My sleep was restless”; 9-“ I felt lonely”; 10- I could not "get going" ], and two on positive affect [i.e., 5- “I felt hopeful about the future”; 8-“I was happy” ]. Options for each item range from “rarely or none of the time” (score of 0) to “all of the time” (score of 3). For example, older adults were asked to rate the frequency with which they experienced this feeling during the past week. The total score ranges between 0 and 30 with a higher score implying more severe symptoms.

Social Participation: Specific types of social participation were measured respectively as separate categorical variables. Participants indicated whether or not they participated in each following social activity during the past month with 10 items from the CHARLS questionnaire: (1) interacting with friends, (2) playing mahjong, chess, or cards or going to a community club, (3) providing help to family, friends, or neighbors who do not live with you, (4) went to a sport, social or other kinds of the club, (5) took part in a community-related organization, (6) did voluntary or charity work, (7) cared for a sick or disabled adult who does not live with you, (8) attended an educational or training course, (9) stock investment, (10) used the Internet [41]. Based on the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA), we classified item 5, item 6, and item 8 into the category of formal activities [33]. The remaining seven were categorized as informal activities.

- Control variables

We controlled for variables that have been shown to affect cognition in addition to depressive symptoms and social participation, including age, gender, education level, marital status, and location of residential address [9-14].

- Statistical analysis

We first performed descriptive statistical analyses on controlled variables, including age, gender, education level, marital status and location of residential address. For deeper analysis, we performed the hierarchical regression model to test the hypothesis. The control variables were placed in the first block of the hierarchical model in Model 0. Following the linearity test, we established the linear relationship between depressive symptoms and cognitive functioning in Model 1. Model 2 allowed us to examine the effect of formal and informal social activities on cognitive functioning. In Model 3, we added interactions between two kinds of social activity and depressive symptoms. To test the effect of each specific social activity, we investigated the effect of ten social activities in Model 4. Similarly, we added interaction between each activity and depressive symptoms in Model 5.

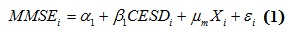

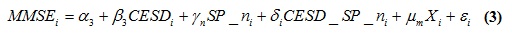

In order to test the impact of social participation and depression on the cognitive functioning of older adults in China, the following hierarchical regression model was established:

where i refers to the individuals in the survey, MMSEi denotes the score each individual obtained on the cognitive assessment tool in this baseline model. For the control variables Xi, we set single illiterate female participants who lived in the special zone as the reference group. ?i is the error term. CESDi denotes the score obtained on the depressive assessment tool. β1 represents the effect of depressive symptoms (CESD-10) on cognitive functioning (MMSE), controlling for Xi while μm represents the effects of control variables on MMSE, holding CESDi constant.

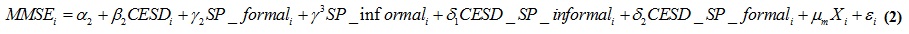

where i refers to the individuals in the survey, MMSEi denotes the score each individual obtained on the cognitive assessment tool in this baseline model. For the control variables Xi, we set single illiterate female participants who lived in the special zone as the reference group. ?i is the error term. CESDi denotes the score obtained on the depressive assessment tool. β1 represents the effect of depressive symptoms (CESD-10) on cognitive functioning (MMSE), controlling for Xi while μm represents the effects of control variables on MMSE, holding CESDi constant.

where SP_formal represents whether the individual i participated in the formal activities while SP_informal represents whether the individual i participated in the informal activities. γ2 represents the difference in MMSEi between older adults who participated in formal social activities versus those who did not participate in any social activities, controlling for other variables including CESD-10. γ3 represents the differences in MMSEi between older adults who participated in informal social activities versus those who did not participate in any social activities, controlling for other variables including CESD-10. CESD_SP_informal represents the interaction between CESD-10 and participating in informal activities, and δ1 represents the effect of interaction between CESD-10 and participating in informal activities, controlling for all other variables. CESD_SP_formal represents the interaction between CESD-10 and participating in formal activities, and δ2 represents the effect of interactions between CESD-10 and participating in formal activities, controlling for all other variables.

where SP_formal represents whether the individual i participated in the formal activities while SP_informal represents whether the individual i participated in the informal activities. γ2 represents the difference in MMSEi between older adults who participated in formal social activities versus those who did not participate in any social activities, controlling for other variables including CESD-10. γ3 represents the differences in MMSEi between older adults who participated in informal social activities versus those who did not participate in any social activities, controlling for other variables including CESD-10. CESD_SP_informal represents the interaction between CESD-10 and participating in informal activities, and δ1 represents the effect of interaction between CESD-10 and participating in informal activities, controlling for all other variables. CESD_SP_formal represents the interaction between CESD-10 and participating in formal activities, and δ2 represents the effect of interactions between CESD-10 and participating in formal activities, controlling for all other variables.

where SP_ni represents whether the individual i participated in the corresponding 10 social activities mentioned in the survey (e.g., SP_1 refers to “interacted with friends”; when SP_n equals to 1 indicating the individual participated in the activities in the past month, SP_n equals to 0 indicating s/he did not) and γi represents the difference in MMSEi between older adults who participated in the particular social activity versus those who did not, controlling for other variables including CESD-10 and the participation of other social activities besides the control variables. CESD_SP_ni represents the interaction between CESD-10 and the specific social participation (e.g., CESD_SP_1 refers to the interaction between CESD-10 and “interacted with friends”), and δi represents the effect of interaction between CESD-10 and the specific social participation, controlling for all other variables.

where SP_ni represents whether the individual i participated in the corresponding 10 social activities mentioned in the survey (e.g., SP_1 refers to “interacted with friends”; when SP_n equals to 1 indicating the individual participated in the activities in the past month, SP_n equals to 0 indicating s/he did not) and γi represents the difference in MMSEi between older adults who participated in the particular social activity versus those who did not, controlling for other variables including CESD-10 and the participation of other social activities besides the control variables. CESD_SP_ni represents the interaction between CESD-10 and the specific social participation (e.g., CESD_SP_1 refers to the interaction between CESD-10 and “interacted with friends”), and δi represents the effect of interaction between CESD-10 and the specific social participation, controlling for all other variables.

Results

- Demographic statistics

The study included 3,284 participants who were selected for analysis. Of these, 2488 (49.20%) were male and 2568 (50.80%) were female. Demographic information can be found in table 1. Older Chinese adults in the CHARLS database demonstrated varying degrees of cognitive impairment (M = 20.96, SD = 5.62), given that an MMSE score of 23 or lower indicates dementia. The subjects also manifested “minimal” to “moderate-severe” depression (M = 8.78, SD = 6.67) with a CESD-10 cut-off score of 10 implying cases of depression. Descriptive statistics for CESD-10 and MMSE scores are presented in table 2. The mean score for the MMSE was 20.96, with a standard deviation of 5.62, while the mean score for the CESD-10 was 8.78, with a standard deviation of 6.67. With a cut-off MMSE score of 23, participants exhibited mixed degrees of cognitive functioning, with some showing mild dementia [51]. A suggested CESD-10 cut-off score of 10 indicated that participants had varying levels of depressive symptoms, with some meeting the score of cases of depression [52].

|

Variables |

|

|

Age (y), M±SD |

69.14±7.15 |

|

Gender, n (%) |

|

|

Male |

2488 (49.20%) |

|

Female |

2568 (50.80%) |

|

Education, n (%) |

|

|

Illiteratea |

1497 (29.60%) |

|

1 to 6 years of education |

2232 (44.10%) |

|

More than 7 years of education |

1327 (26.20%) |

|

Marital status, n (%) |

|

|

Married |

3989 (78.90%) |

|

Divorced |

40 (0.80%) |

|

Widowed |

995 (19.70%) |

|

Never Marrieda |

32 (0.60%) |

|

Location of residential address, n (%) |

|

|

Central of city/town |

1050 (20.80%) |

|

Urban-rural integration zone |

348 (6.90%) |

|

Rural areas |

3644 (72.10%) |

|

Special zonea |

14 (0.30%) |

Table 1: The demographic information of selected subjects (n = 5056).

|

Variables |

|

|

MMSE, M±SD |

20.9 ±5.62 |

|

CESD-10, M±SD |

8.78±6.67 |

|

SP: have at least one social participation, n (%) |

2743 (54.3%) |

|

SP_informal: have at least one informal social participation, n (%) |

217 (4.30%) |

|

SP_formal: have at least one formal social participation, n (%) |

2720 (53.80%) |

|

SP_1: interacting with friends, n (%) |

1773 (35.10%) |

|

SP_2: playing mahjong, chess, or cards or going to a club, n (%) |

887 (17.50%) |

|

SP_3: providing help to family, friends not living with you, n (%) |

723 (14.30%) |

|

SP_4: went to a sport, social or other kinds of the club, n (%) |

340 (6.70%) |

|

SP_5: took part in a community-related organization, n (%) |

136 (2.70%) |

|

SP_6: did voluntary or charity work, n (%) |

87 (1.70%) |

|

SP_7: caring for a sick or disabled adult not living with you, n (%) |

160 (3.20%) |

|

SP_8: attended an educational or training course, n (%) |

43 (0.90%) |

|

SP_9: stock investment, n (%) |

41 (0.80%) |

|

SP_10: used the Internet, n (%) |

659 (13.00%) |

Table 2: The descriptive statistics of MMSE scores, CESD-10 scores, and social participation.

- Depression and Formal/Informal social participation on cognitive functioning

Table 3 presents the results from the hierarchical regression models for the cognitive functioning of older adults (n = 5,056) when considering depression, formal social participation, and informal participation, controlling for demographic information. Model 1 considered the role of depression on older adults’ cognitive functioning. Results showed that depression was negatively associated with older adults’ cognitive functioning; in detail, older adults who experienced higher levels of depression showed reduced cognitive functioning (β = -0.195, p < 0.001).

Model 2 involved formal social participation and informal social participation in the model compared with Model 1. Both formal social participation and informal social participation helped better explain the cognitive functioning of older adults (R2 = 0.99, p< 0.001). Participating in formal social activities (ß = 0.970, p < 0.05) and informal social activities (β = 0.458, p < 0.01) significantly improved older adults’ cognitive functioning. Model 3 examined how the interaction of depression and formal social participation and/or the interaction of depression and informal social participation might affect cognitive functioning. The current research did not find significant interactions, that is, formal social activities (β = -0.048, p> 0.05) or informal social activities (β = 0.029, p> 0.05) would not alter the relationship between older adults' depression level and cognitive functioning.

- Depression and specific types of social participation on cognitive functioning

In table 3, social participation (i.e., both formal and informal) was broken down into the 10 sub-categories in Model 4 and Model 5 to investigate which specific types of social participation improve cognitive functioning. The interaction effect between each type of social participation and depression was additionally explored in Model 5. In alignment with previous models, the CESD-10 score remained significant across Model 4 (β = -0.189, p < 0.001) and Model 5 (β = -0.200, p< 0.001), indicating a negative main effect of depression on cognitive functioning.

Model 4 showed that three types of informal social participation, “played mahjong, chess, or cards or went to a community club” (SP_2) (β = 0.571, p< 0.01), “went to a sport, social or other kinds of the club” (SP_4) (β = 0.899, p < 0.01), and “stock investment” (SP_9) (β = 1.883, p < 0.05) had a significant positive main effect on the MMSE score of older Chinese adults, while only one type of formal social participation, “took part in a community-related organization” (SP_5) (β = 1.003, p < 0.05), positively affected older adults’ cognitive functioning. Particularly, “stock investment” (SP_9) had the greatest positive coefficient, suggesting that older adults who invested in stocks scored 1.883 units higher on MMSE compared to those who did not, controlling for all other variables.

No interaction effects between specific types of social participation and depression on cognitive functioning were found for older Chinese adults in Model 5. Adding the interaction terms did not enhance the explanatory power of the model (R2 = 0.109, p = 0.518). While Model 5 failed to detect any moderating effect of social participation on depression’s influence on cognitive functioning, the absolute value of the depression coefficient increased by 0.011 units (β = -0.200, p < 0.001), indicating that depression may play a role in negatively affecting social participation’s influence on cognitive functioning.

|

Variable |

Model 0 |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

|

Constant |

18.914 (1.924) |

20.680 (1.873) |

20.275 (1.873) |

20.332 (1.873) |

20.391 (1.868) |

20.463 (1.869) |

|

age |

0.026* (0.012) |

0.023* (0.011) |

0.023* (0.011) |

0.023* (0.011) |

0.022* (0.011) |

0.022 (0.011) |

|

Gender_male |

-0.439*(0.170) |

-0.459**(0.165) |

-0.463**(0.165) |

-0.463**(0.165) |

-0.0480**(0.164) |

-0.482**(0.164) |

|

education_1to6 |

1.048*** (0.195) |

0.942*** (0.190) |

0.936*** (0.190) |

0.932*** (0.190) |

0.945*** (0.189) |

0.929*** (0.190) |

|

Education_7more |

2.135*** (0.241) |

1.849*** (0.235) |

1.829*** (0.234) |

1.824*** (0.234) |

1.828*** (0.234) |

1.804*** (0.235) |

|

Marital_married |

-.954 (0.980) |

-1.088 (0.952) |

-1.117 (0.951) |

-1.091 (0.951) |

-1.074 (0.949) |

-.964 (0.951) |

|

Marital_divorced |

-.807 (0.537) |

-.693 (1.271) |

-.752 (1.269) |

-.704 (1.270) |

-.717 (1.266) |

-0.572 (1.269) |

|

Marital_widowed |

-1.509 (0.996) |

-1.535 (0.968) |

-1.570 (0.967) |

-1.549 (0.967) |

-1.523 (0.965) |

-1.402 (0.967) |

|

Residential_city |

1.702 (1.481) |

1.969 (1.440) |

2.082 (1.439) |

2.117 (1.439) |

1.867 (1.436) |

1.870 (1.437) |

|

Residential_integration |

1.363 (1.499) |

1.673 (1.457) |

1.811 (1.457) |

1.844 (1.457) |

1.608 (1.453) |

1.559 (1.455) |

|

Residential_rural |

0.109 (1.472) |

.505 (1.431) |

0.663 (1.430) |

0.691 (1.431) |

0.536 (1.427) |

0.504 (1.428) |

|

CESD |

|

-.195***(0.011) |

-.192***(0.011) |

-.206***(0.016) |

-0.189***(0.011) |

-0.200***(0.015) |

|

SP_informal |

|

|

.970* (0.375) |

1.356* (0.603) |

|

|

|

SP_formal |

|

|

0.458** (0.153) |

.199 (0.253) |

|

|

|

CESD_SP_informal |

|

|

|

-0.048 (0.060) |

|

|

|

CESD_SP_formal |

|

|

|

0.029 (0.023) |

|

|

|

SP_1 |

|

|

|

|

-0.008 (0.167) |

-0.045 (0.275) |

|

SP_2 |

|

|

|

|

0.571** (0.202) |

0.632 (0.330) |

|

SP_3 |

|

|

|

|

0.045 (0.229) |

-0.260 (0.381) |

|

SP_4 |

|

|

|

|

0.899** (0.310) |

0.685 (0.356) |

|

SP_5 |

|

|

|

|

1.003* (0.491) |

0.789 (0.784) |

|

SP_6 |

|

|

|

|

-0.907 (0.608) |

0.097 (1.001) |

|

SP_7 |

|

|

|

|

.431 (0.440) |

1.192 (0.716) |

|

SP_8 |

|

|

|

|

1.033 (0.849) |

1.695 (1.430) |

|

SP_9 |

|

|

|

|

1.883* (0.857) |

2.471 (1.399) |

|

SP_10 |

|

|

|

|

.590 (0.235) |

0.024 (0.366) |

|

CESD_SP_1 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.005 (0.025) |

|

CESD_SP_2 |

|

|

|

|

|

-.0007 (0.032) |

|

CESD_SP_3 |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.034 (0.035) |

|

CESD_SP_4 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.028 (0.050) |

|

CESD_SP_5 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.029 (0.079) |

|

CESD_SP_6 |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.124 (0.099) |

|

CESD_SP_7 |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.086 (0.065) |

|

CESD_SP_8 |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.085 (0.147) |

|

CESD_SP_9 |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.088 (0.174) |

|

CESD_SP_10 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.073 (0.036) |

|

R2 |

0.045 |

0.098 |

0.101 |

0.102 |

0.108 |

0.109 |

|

Adjusted R2 |

0.043 |

0.096 |

0.099 |

0.099 |

0.104 |

0.104 |

Table 3: Regression results for MMSE.

Note: Standard errors are reported in parentheses.

Note: education_1 to 6 = have 1 to 6 years of education, education_7 more = have more than 7 years of education; marital_married = marital status is married, marital_divorced = married status is divorced, marital_widowed = married status is widowed; residential_city = mainly live in the central of city/town, residential_integration = mainly live in urban-rural integration zone, residential_rural = mainly live in rural areas; CESD = depression; SP_informal = have at least one informal social participation; SP_formal = have at least one formal social participation; CESD_SP_informal = the interaction term of CESD and SP_informal; CESD_SP_formal = the interaction term of CESD and SP_formal; SP_1 = “interacted with friends”, SP_2 = “played mahjong, chess, or cards or went to a community club”, SP_3 = “provided help to family, friends or neighbors who do not live with you”, SP_4 = “went to a sport, social or other kinds of the club”, SP_5 = “took part in a community-related organization”, SP_6 = “did voluntary or charity work”, SP_7 = “cared for a sick or disabled adult who does not live with you”, SP_8 = “attended an educational or training course”, SP_9 = “stock investment”, SP_10 = “used the Internet”; CESD_SP_n = the interaction term of CESD and SP_n, n ranges from 1 to 10.

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

The current study revealed a direct negative association between depression and cognitive functioning. It further discovered that both formal and informal social participation mitigate cognitive decline among the older Chinese population. It was found that “playing mahjong, chess, or cards or going to a community club”, “going to a sport, social or other kinds of the club”, “taking part in a community-related organization”, and “investing in stock” were particularly helpful in preventing cognitive decline. Importantly, no interaction between social participation and depression on cognitive functioning was found, indicating a failure to detect a modifying effect of social participation on depression’s relationship with cognitive functioning.

The study’s findings generally replicated previous research on the negative correlation between depression and cognitive functioning among older adults [22,53-55]. Depression plays a significant role in affecting cognitive decline among older adults, even after controlling for demographic factors and social participation. The study also aligned with prior studies on the benefit of social participation on cognitive functioning. More consistent and frequent social engagement was shown to correlate with more favorable cognitive aging trajectories as well as higher cognitive functioning among older adults [36,56,57].

The results of this study suggested that formal social participation has a significant positive effect on the cognitive functioning of older Chinese adults. Specifically, participating in community-related organizations was found to be associated with higher scores on the cognitive test. This finding bridged a gap in the field as previous research primarily focused on informal social activities, such as playing mahjong or cards and interacting with friends [58]. The inclusion of formal activities in this study highlighted the importance of considering the diverse range of social activities that older adults engage in and their potential impact on cognitive functioning.

In comparison to similar studies in China, the finding that formal social activities have a positive effect on cognitive functioning was consistent with previous research. For example, Luo et al., [59] also found that participation in formal social activities, such as volunteer work, was associated with better cognitive functioning in older adults. However, the specific types of formal activities that have a positive effect on cognitive functioning may vary across cultural contexts. In a Korean longitudinal population-based study, older adults who participated in senior citizen clubs or senior centers had better cognitive functioning [33]. These findings suggested that promoting formal social activities may be a valuable strategy for improving cognitive functioning in older adults and that tailoring interventions to the specific cultural context may be important.

The results of the current study showed that informal social participation had a positive association with cognitive functioning. Specifically, informal activities such as “playing mahjong, chess, or cards”, “going to a community or social club”, and “stock investment” were found to have a significant positive effect on cognitive functioning. These results aligned with previous studies. In comparison to similar studies in China, the study by Fu et al., [60] found that participating in informal social activities, such as visiting friends or relatives, was positively associated with cognitive functioning among older adults in China, while the current study showed that older adults who engaged in more informal social activities had better cognitive functioning, including better attention, memory, and processing speed. Moreover, Tomioka et al., [61] found that engaging in informal social activities, such as visiting friends or relatives, was associated with a lower risk of cognitive decline. Similarly to our findings, participants who engaged in more than one activity per week had a lower risk of cognitive decline compared to those who did not engage in any activities.

The current study failed to find the interaction effect between social participation and depression on cognitive functioning. To be more specific, participating in formal or informal social activities did not significantly alter the impact of depression on the cognitive level of older Chinese adults. In addition, the interaction effect was not found when considering specific types of social participation either. This result did not support previous indications. One possible reason is that the number of older adults participating in formal activities in our sample was much smaller than those participating in informal activities, suggesting potential insufficient power for detecting the interaction effect. Additionally, the cognitive functioning of older adults was influenced by a bunch of factors, including demographic factors, mental health conditions, and so on [8,-14,22]. A non-significant interaction effect might be a result of the highly complex interrelationships among these factors.

Limitations and Future Direction

One limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which makes it difficult to draw causal conclusions about the relationship between depression, social participation, and cognitive functioning. Longitudinal studies that follow older adults over time would provide stronger evidence of causality and allow for the examination of the temporal relationships between these variables. Future studies could aim at drawing conclusions about the potential causal relationships. Additionally, the dataset used in this study relied on self-reported measures of social participation, which may be subject to recall bias and social desirability bias. Future studies could use objective measures of social participation, such as attendance records or activity logs, to provide more accurate data. Finally, the study focused on older Chinese adults, and the results may not be generalizable to other populations with different cultural and social contexts. Therefore, caution should be taken when applying these findings to other populations. Based on that, collecting information on other potentially relevant factors such as physical health, lifestyle factors, and environmental factors would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay between depression, social participation, and cognitive functioning in older adults.

Conclusion

Overall, this study replicated previous research on the correlation between depression and cognitive decline and, more importantly, supported the idea that both formal and informal social participation benefit cognitive functioning. Particularly, stock investment, as a type of informal social participation, has a greater impact than other types of social participation on improving cognitive functioning among older Chinese adults. This study contributes to existing knowledge through evidence-based statistical analyses. The insights of this study will be of interest to Chinese policymakers, geriatric institutions and communities, psychologists, doctors, and older adults in improving the national mental health states of older Chinese adults.

Declarations

- Ethics approval and consent to participate

In this study, all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was waived of IRB approval by the Ethics Committee of Kunming Medical University (Ethic number: KMMU2021MEC118). As the data received for analysis was already de-identified, and there was no new data collection or interaction with human subjects involved, IRB approval was not required for this analysis. The secondary analysis of CHARLS data in this study was conducted under the CHARLS Data Sharing Agreement, which outlines the conditions for accessing and utilizing the data while ensuring participant privacy and confidentiality. The CHARLS study itself was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015).

- Consent for publication

Not applicable.

- Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) repository, http://charls.pku.edu.cn/en/. Access to the data requires registration and a request process. To obtain the data, interested researchers should register an account using their email address on the CHARLS dataset website. Once registered, researchers can navigate to the specific wave of data relevant to their study and click the “apply” button to send a request. After the request is reviewed and permission is granted, the "apply" button will be replaced with a "download" button. Researchers can then click the "download" button to obtain the dataset.

- Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

- Funding

This study was financially funded by Yunnan Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (Grant Number: ZD202115) and the Aging Health Management Technology Innovation Team of Kunming Medical University (Grant Number: CXTD202103).

- Authors’ contributions

MX conceived and designed the study. DM conducted the literature review. GR and ZP performed the statistical analyses and prepared the tables. RL reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revisions and approved the final version.

- Acknowledgment

The authors would like to express their sincerest gratitude to Dr. Youmi Suk at Teachers College for her invaluable guidance and unwavering support throughout this project. Her mentorship has been instrumental in transforming this course project into a research paper. The authors are immensely grateful for her contribution and support throughout this journey.

References

- Guo C, Zheng X (2018) Health challenges and opportunities for an aging China. Am J Public Health 108: 890-892.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China (2023) The 2020 population by nationality, gender and age. NBSC, Beijing, China.

- Chen R, Hu Z, Wei L, Liu Z, Peng Y, et al. (2021) Prevalence and risk factors for cognitive impairment among older adults in China: a systematic review. Aging Clin Exp Res: 1-14.

- Xue J, Li J, Liang J, Chen S (2018) The Prevalence of Mild Cognitive Impairment in China: A Systematic Review. Aging Dis 9: 706-715.

- Barnes DE, Cauley JA, Lui LY, Fink HA, McCulloch C, et al. (2007) Women who maintain optimal cognitive function into old age. J Am Geriatr Soc 55: 259-264.

- Fratiglioni L, Qiu C (2011) Prevention of cognitive decline in ageing: Dementia as the target, delayed onset as the goal. Lancet Neurol 10: 778-779.

- Geda YE (2012) Mild cognitive impairment in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep 14: 320-327.

- Tervo S, Kivipelto M, Hänninen T, Vanhanen M, Hallikainen M, et al. (2004) Incidence and risk factors for mild cognitive impairment: A population-based three-year follow-up study of cognitively healthy elderly subjects. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 17: 196-203.

- Zhang Q, Wu Y, Han T, Liu E (2019) Changes in cognitive function and risk factors for cognitive impairment of the elderly in China: 2005-2014. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16: 2847.

- Hwang J, Kim S, Kim S (2021) Gender differences in the impact of depression on cognitive decline among Korean older adults. Asia Pac J Public Health 33: 67-75.

- Xu PR, Wei R, Cheng BJ, Wang AJ, Li XD, et al. (2021) The association of marital status with cognitive function and the role of gender in Chinese community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study. Aging Clin Exp Res 33: 2273-2281.

- Yang L, Cheng J, Wang H (2021) Place of residence and cognitive function in older adults in China: The mediating role of social participation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19: 13.

- Yin S, Xiong J, Zhu X, Li R, Li J (2022) Cognitive training modified age-related brain changes in older adults with subjective memory decline. Aging Ment Health 26: 1997-2005.

- Zhu X, Qiu C, Zeng Y, Li J (2017) Leisure activities, education, and cognitive impairment in Chinese older adults: A population-based longitudinal study. Int Psychogeriatr 29: 727-739.

- Evans IEM, Llewellyn DJ, Matthews FE, Woods RT, Brayne C, et al. (2019) Living alone and cognitive function in later life. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 81: 222-233.

- Nyberg L, Pudas S (2019) Successful memory aging. Annu Rev Psychol 70: 219-243.

- Yaffe K, Fiocco AJ, Lindquist K, Vittinghoff E, Simonsick EM, et al. (2009) Predictors of maintaining cognitive function in older adults: The Health ABC study. Neurology 72: 2029-2035.

- Li D, Zhang DJ, Shao JJ, Qi XD, Tian L (2014) A meta-analysis of the prevalence of depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 58: 1-9.

- Cui L, Ding D, Chen J, Wang M, He F, et al. (2022) Factors affecting the evolution of Chinese elderly depression: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 22: 109.

- Ribeiro O, Teixeira L, Araújo L, Rodríguez-Blázquez C, Calderón-Larrañaga A, et al. (2020) Anxiety, depression and quality of life in older adults: Trajectories of influence across age. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 9039.

- Peng S, Wang S, Feng XL (2021) Multimorbidity, depressive symptoms and disability in activities of daily living amongst middle-aged and older Chinese: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. J Affect Disord 295: 703-710.

- Zhou L, Ma X, Wang W (2021) Relationship between cognitive performance and depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults: The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). J Affect Disord 281: 454-458.

- Hu Y, Lei X, Smith JP, Zhao Y (2012) Effects of social activities on cognitive functions: Evidence from CHARLS. Aging in Asia: Findings From New and Emerging Data Initiatives.

- Li C, Jiang S, Zhang X (2019) Intergenerational relationship, family social support, and depression among Chinese elderly: A structural equation modeling analysis. J Affect Disord 248: 73-80.

- Paterniti S, Verdier-Taillefer MH, Dufouil C, Alpérovitch A (2002) Depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in elderly people. Longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry 181: 406-410.

- Su D, Chen Z, Chang J, Gong G, Guo D, et al. (2020) Effect of social participation on the physical functioning and depression of empty-nest elderly in China: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey (CHARLS). Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 9438.

- Choi E, Han KM, Chang J, Lee YJ, Choi KW, et al. (2021) Social participation and depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults: Emotional social support as a mediator. J Psychiatr Res 137: 589-596.

- Shimada H, Park H, Makizako H, Doi T, Lee S, et al. (2014) Depressive symptoms and cognitive performance in older adults. J Psychiatr Res 57: 149-156.

- Wei J, Ying M, Xie L, Chandrasekar EK, Lu H, et al. (2019) Late-life depression and cognitive function among older adults in the U.S.: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2014. J Psychiatr Res 111: 30-35.

- Glei DA, Landau DA, Goldman N, Chuang YL, Rodríguez G, et al. (2005) Participating in social activities helps preserve cognitive function: An analysis of a longitudinal, population-based study of the elderly. Int J Epidemiol 34: 864-871.

- Wang X, Guo J, Liu H, Zhao T, Li H, et al. (2022) Impact of social participation types on depression in the elderly in China: An analysis based on counterfactual causal inference. Front Public Health 10: 792765.

- Lemon BW, Bengtson VL, Peterson JA (1972) An exploration of the activity theory of aging: Activity types and life satisfaction among in-movers to a retirement community. J Gerontol 27: 511-523.

- Lee SH, Kim YB (2016) Which type of social activities may reduce cognitive decline in the elderly?: A longitudinal population-based study. BMC Geriatr 16: 165.

- Lee SH, Kim YB (2014) Which type of social activities decrease depression in the elderly? An analysis of a population-based study in South Korea. Iran J Public Health 43: 903-912.

- Kelly ME, Duff H, Kelly S, McHugh Power JE, Brennan S, et al. (2017) The impact of social activities, social networks, social support and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review. Syst Rev 6: 259.

- Li H, Li C, Wang A, Qi Y, Feng W, et al. (2020) Associations between social and intellectual activities with cognitive trajectories in Chinese middle-aged and older adults: A nationally representative cohort study. Alzheimers Res Ther 12: 115.

- Zhao Y, Li C, Gao L, Li Y, Li R, et al. (2019) Effectiveness of physical, cognitive, and social interventions on cognition and depression for Chinese older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 257: 668-677.

- Dolberg P, Ayalon L (2018) Subjective meanings and identification with middle age. Int J Aging Hum Dev 87: 52-76.

- Lee SB, Oh JH, Park JH, Choi SP, Wee JH (2018) Differences in youngest-old, middle-old, and oldest-old patients who visit the emergency department. Clin Exp Emerg Med 5: 249-255.

- Chen X, Wang Y, Strauss J, Zhao Y (2019) China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). In: Gu D, Dupre M (eds.). Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging. Springer, Berlin, Germany.

- Zhao Y, Strauss J, Chen X, Wang Y, Gong J, et al. (2020) China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study Wave 4 User’s Guide. National School of Development, Peking University, Beijing, China.

- Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G (2014) Cohort profile: The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol 43: 61-68.

- Tussey CM, Broshek DK, Marcopulos BA (2010) Delirium Assessment in Older Adults. In: Bracken A (ed.). Handbook of Assessment in Clinical Gerontology (2ndedn). Elsevier: 179-210.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: 189-198.

- Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Smailagic N, Roqué I Figuls M, Ciapponi A, Sanchez-Perez E, et al. (2015) Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015: CD010783.

- Gao MY, Yang M, Kuang WH, Qiu PY (2015) [Factors and validity analysis of Mini-Mental State Examination in Chinese elderly people]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 47: 443-449.

- Tan TK, Feng Q (2022) Validity and reliability of Mini-Mental State Examination in older adults in China: Inline Mini-Mental State Examination with cognitive functions. Int J Popul Stud 8: 1-16.

- Marioni RE, Chatfield M, Brayne C, Matthews FE (2011) The reliability of assigning individuals to cognitive states using the Mini Mental-State Examination: A population-based prospective cohort study. BMC Med Res Methodol 11: 127.

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL (1994) Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med 10: 77-84.

- Boey KW (1999) Cross-validation of a short form of the CES-D in Chinese elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 14: 608-617.

- Gluhm S, Goldstein J, Loc K, Colt A, Liew CV, et al. (2013) Cognitive performance on the Mini-Mental State Examination and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment across the healthy adult lifespan. Cogn Behav Neurol 26: 1-5.

- Fu H, Si L, Guo R (2022) What is the optimal cut-off point of the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for screening depression among Chinese individuals aged 45 and over? An exploration using latent profile analysis. Front Psychiatry 13: 820777.

- Liu J, Qiang F, Dang J, Chen Q (2023) Depressive Symptoms as Mediator on the Link between Physical Activity and Cognitive Function: Longitudinal Evidence from Older Adults in China. Clin Gerontol 46: 808-818.

- Zhang N, Chao J, Cai R, Bao M, Chen H (2023) The association between longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms and cognitive decline among middle-aged and older Chinese adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 109: 104960.

- Liu Y, Xu Y, Yang X, Miao G, Wu Y, et al. (2023) Sensory impairment and cognitive function among older adults in China: The mediating roles of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 38: 5866.

- Fernández I, García-Mollá A, Oliver A, Sansó N, Tomás JM (2023) The role of social and intellectual activity participation in older adults’ cognitive function. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 107: 104891.

- Oh SS, Cho E, Kang B (2021) Social engagement and cognitive function among middle-aged and older adults: Gender-specific findings from the Korean longitudinal study of aging (2008–2018). Sci Rep 11: 1-9.

- Glance LG, Dick AW, Osler TM, Mukamel DB, Li Y, et al. (2012) The association between nurse staffing and hospital outcomes in injured patients. BMC Health Serv Res 12: 1-11.

- Luo Y, Pan X, Zhang Z (2019) Productive activities and cognitive decline among older adults in China: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Soc Sci Med 229: 96-105.

- Fu C, Li Z, Mao Z (2018) Association between social activities and cognitive function among the elderly in China: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15: 231.

- Tomioka K, Kurumatani N, Hosoi H (2018) Social participation and cognitive decline among community-dwelling older adults: A community-based longitudinal study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 73: 799-806.

Citation: Ma X, Zheng P, Guo R, Du M, Ran L (2023) Does Social Participation Modify the Association between Depression and Cognitive Functioning among Older Adults in China? A Secondary Analysis based on CHARLS. J Gerontol Geriatr Med 9: 189.

Copyright: © 2023 Xinyue Ma, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.