Ethical Challenges Experienced by Older Adults with Cognitive Impairments in the Continuum of Health and Social Services: Examples Drawn From the Professional Experiences of Occupational Therapists

*Corresponding Author(s):

Marie-Michèle LordDepartment Of Occupational Therapy, Université Du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Canada

Email:Marie-Michele.Lord@uqtr.ca

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1], 47.5 million people worldwide were affected by major neurocognitive disorder, characterized by symptoms that impact cognitive function. More specifically, in Canada, in 2018, there were approximately 452,000 individuals over the age of 65 diagnosed with major neurocognitive disorder [2], while in 2020, 597,000 Canadians were living with cognitive impairments, and this number is expected to reach 955,900 people by 2030. Considering the aging population and significant medical advances that extend life expectancy, in Canada as in other part of the world, the number of people living with cognitive impairments is projected to increase in the coming decades [3].

Major neurocognitive disorder is a chronic condition typically characterized by a decline in cognitive functions, changes in physical condition, as well as mood and behavioral alterations [4]. The DSM-5 diagnosis of Major Neurocognitive Disorder, which corresponds to dementia, requires substantial impairment to be present in one or (usually) more cognitive domains. The impairment must be sufficient to interfere with independence in everyday activities [5]. The increasing number of individuals affected by cognitive impairments and major neurocognitive disorder suggests a correlated rise in the demand for healthcare and social services for this population [6]. Indeed, cognitive issues are one of the reasons associated with the use of hospital services among seniors with the highest frequency of use [7]. In Canada, care, and services for older adults with cognitive impairments can be provided in various settings, including at home, in hospitals, in long-term care facilities, depending on the level of care needed and the specific requirements of the individuals.

Due to the multifaceted decline observed in individuals with major neurocognitive disorder, including affective, cognitive, behavioral, linguistic, physical, and visual aspects, they often become vulnerable to their environment. Individuals living with major neurocognitive disorder depend on those who provide care, especially in the later stages of the disease [8,9]. This dependence puts their autonomy, dignity, and integrity at risk [10,11]. The likelihood of experiencing situations of mistreatment is further elevated when older adults have cognitive impairments [12,13]. As explained by Lacour [14], "vulnerability can be likened to a chink in the armor. It represents a significant weakness that exposes the individual to abusive infringements in their civil life, affecting their ability to make personal decisions necessary for their health and safety, such as medical procedures and choice of living arrangements" (p.188). In this context, it is not surprising that the ethical scrutiny around major neurocognitive disorder has largely focused on two central issues: a) consent, and b) ethical issues surrounding scientific research involving individuals with the disease [15,16]. In both cases, the capacity of individuals with cognitive decline to make free and informed choices is the main highlighted concern.

While these two areas of ethical reflection have been addressed in the literature, the ethical challenges experienced by older adults with cognitive impairments have not been extensively studied, particularly regarding their experiences within the continuum of healthcare and social services. For example, what ethical challenges do older adults having cognitive impairments encounter when receiving care and services? A few articles discuss the perspectives of various healthcare professionals on the challenges of providing care to individuals with major neurocognitive disorder. Indeed, documenting the perspective of healthcare professionals is valuable, as they are not only witnessing to the daily situations that arise but are also at the forefront of the ethical challenges experienced by older adults.

In this context, a study aimed at documenting the ethical challenges encountered by occupational therapists in their practice has contributed to a better understanding of what older adults with cognitive impairments may experience [17]. Occupational therapists are among the healthcare professionals frequently involved in the care of elderly individuals. They work to support the realization of meaningful occupations, i.e., activities that are important to the individuals. They are also involved in the assessment of the capacities of elderly individuals, especially when it comes to potential relocation to long-term care facilities, restraint protocols, or assessments of the capacity to drive a motor vehicle. Through their holistic view of the individual and their interventions in daily life and living environments, occupational therapists are professionals who can shed light on the complexity of situations experienced by patients, including the elderly and their families. They have played a crucial role in understanding various ethical challenges in healthcare practice [18-20].

This article aims to highlight the ethical challenges experienced by older adults with cognitive impairments, as raised by occupational therapists working in the continuum of healthcare and social services in Canada (specifically, in the province of Quebec).

Theoretical Framework

In this article, an ethical challenge is defined as a situation that compromises, in whole or in part, the respect for at least one value considered legitimate and desirable. Several theoretical frameworks are used to document ethical challenges. Among these, the framework proposed by Swisher and her colleagues [21]. Developed from a bioethical perspective, allows for the documentation of a broad spectrum of ethical challenges, including: 1) the ethical dilemma, which corresponds to a situation where at least two legitimate and desirable ethical values come into conflict; 2) the ethical temptation, which refers to a situation where there is a temptation to choose an option that is not ethical due to personal or organizational benefits derived from that option; 3) the ethical silence, which pertains to a situation where at least one value is violated, but no one discusses it for various reasons; and 4) the ethical distress, which corresponds to a situation where the healthcare professional encounters a barrier to realizing an ethical good and experiences a certain psychological distress.

Methodology

The main objective of the conducted research was to document the ethical challenges experienced by occupational therapists in the context of their practice with older adults in the continuum of healthcare and social services. To achieve this objective, an inductive and qualitative phenomenological and descriptive design [22] was employed. This design was chosen because it allows the exploration of phenomena based on the perceptions and experiences of privileged actors of the phenomenon under scrutiny, aiming to develop an understanding of it.

Specifically, participant recruitment was conducted through the Ordre des ergothérapeutes du Québec (OEQ), a structure that governs, frames, and regulates the practice of occupational therapy in Quebec. OEQ reached out to all occupational therapists holding a valid practice permit. Participants who agreed to take part in the study were individually interviewed in semi-structured interviews lasting 60 to 90 minutes. The interview guide was based on Swisher and her colleagues' framework [23].

The qualitative analysis of the verbatim was carried out following the fundamental principles of phenomenological reduction. More precisely, the steps proposed by Giorgi [21] for conducting phenomenological reduction were followed, including a careful and repeated reading of the verbatim by two analysts, the gradual creation of units of meaning, as well as the organization and formulation of the data in disciplinary language [24]. This analysis helped to identify the ethical challenges experienced by older adults with cognitive impairments, as reported by the interviewed occupational therapists. Finally, ethical certification was obtained from the research ethics committee with human subjects at the University of Quebec at Trois-Rivières.

Results

This section presents the results of the study. The research participants are firstly described, followed by the ethical challenges. The units of meaning are illustrated by excerpts from the interview transcripts.

Study Participants

Seventy occupational therapists (n=70) working with older adults participated in the study, including sixty women (n=60) and ten men (n=10). Fifty of them were practitioners (n=50), and twenty were occupational therapists working in managerial roles (n=20) within the healthcare system. Their practice settings were diverse, including home support (n=15), intensive functional rehabilitation units (n=5), private practice (n=7), hospital settings (n=22), and long-term care hospitals (n=21).

Ethical Challenges

Ethical challenges faced by older adults with cognitive impairments were identified by the participants across their practice settings. As illustrated in Figure 1, four major categories of ethical challenges were identified: 1) the tyranny of safety, 2) disregarded decisional and functional autonomy, 3) violated privacy, and 4) limited access to care.

Figure 1: Ethical challenges experienced by older adults living with cognitive impairment.

Figure 1: Ethical challenges experienced by older adults living with cognitive impairment.

Tyranny of Safety

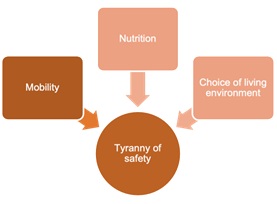

Participants emphasize that safety is a strong value within the healthcare and social services network that systematically takes precedence over other legitimate and desirable ethical values, such as health, autonomy, well-being, or freedom especially in the intervention with older adults who have cognitive impairments. Safety becomes a constraining value in three main situations: a) mobility, b) nutrition, and c) the choice of living environment, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Situations where the tyranny of safety predominates.

Figure 2: Situations where the tyranny of safety predominates.

First, due to the perceived increased risk of falls in individuals with cognitive impairments, healthcare professionals tend to restrict the freedom of older adults through constraints (e.g., restraints). When opportunities for free movement are reduced, this can lead to even faster functional declines than the major neurocognitive disorder itself would cause. The lack of resources exacerbates the problem, limiting the actions possible for healthcare professionals who sometimes must opt for the most restrictive option due to the inability to offer better, as explained by participant 36:

"It's almost 90% of my daily work [devoted to] managing falls. If a client starts to fall, and [it's impossible] to let them walk unsupervised because of very advanced major neurocognitive disorder, they should benefit from a walking assistive device, or we could find an alternative (…) but if the equipment is not available (…), I'm forced to opt for restraint."

Travel by car is also immediately questioned when an older adult has cognitive impairments even in light stage of the disease. Because the speed of intervention must check to be uniform maintained, driving licenses are withdrawn quickly, often preventively, and sometimes without a thorough assessment of the situation. In acute care at the hospital, patients may sometimes experience a delirium, which can resemble major neurocognitive disorder but could be reversible when the cause (e.g. urinary infection) is treated. It may happen that older adults are hospitalized for a health problem and the onset of cognitive impairments immediately triggers an evaluation of their driving ability, even if the cognitive impairments are temporary exacerbated:

"A person can come here for treatment and, ultimately, end up with a report to revoke their driver's license. It's done for a good reason, for everyone's safety, including the patient's, but for the patient, it's terrible because you come to the hospital to get treated, and eventually they take away your freedom by evaluating you and proposing to revoke your driver's license." (Participant 49).

Next, in the case of nutrition, the tyranny of safety often results in a strict dietary regimen, leaving little room for the desires of older adults with cognitive impairments. The risk of choking is not tolerated by the healthcare system, even if patients wish to take that risk. Participant 43 describes this situation:

"We want to have zero risk of choking, [so we plan] dedicated snacks, meaning that for this person, they are entitled to a yogurt. If the person doesn't want a yogurt (…) but a small biscuit with cheese, I can't [respect their choice]."

Furthermore, discontinuing food intake can be a difficult choice for families of individuals with cognitive impairments, and the option of maintaining life at all costs is often favored, regardless of the quality of life.

"For some families (…), preserving life at all costs, moving towards tube feeding, is often the first option that comes to mind, even if it reduces the quality of life (…) Often, with the elderly clientele population?, when the level of major neurocognitive disorder is very advanced, oral feeding is no longer possible, and tube feeding is used, but is it really a good intervention for the patient?" (Participant 20).

Patients whose major neurocognitive disorder is deemed to be at an advanced stage are no longer consulted when making this crucial decision, which then relies on family.

Finally, respecting the choice of a living environment is complex when an older adult has cognitive impairments. The relocation process is primarily based on an evaluation that considers the level of required care and risk factors but pays little attention to protective factors and the desires of the elderly individual, especially if they have cognitive impairments. Safety takes a predominant place in the decision-making balance, as explained by participant 34:

"In evaluating my client, my observations lead me to believe that he has enough capacity to stay at home and decide about his living environment (…), that he could go back home. But since capacity cases are mainly managed by social workers and doctors, I felt that we were going down the predetermined path for people with cognitive impairments, towards relocation."

Participants also highlight that false choices are given to older adults with cognitive impairments to compel them to choose the option that healthcare providers or caregiver’s desire:

"Also, decisions are often made on behalf of the elderly person [by the team or family]. Or they are asked to choose between two options they say they don't want, for example, accepting home services and assistance from their family, or relocating, even though we know they don't want help or to change their living environment." (Participant 34). All of this is in the name of safety deemed essential and more important than free choice.

Disregarded Decisional and Functional Autonomy

Once older adults experience cognitive losses, efforts made by healthcare professionals to obtain free, informed, and ongoing consent diminish. Decisions are made by others than the older adults themselves, as if this approach were legitimate, and normal:

"Sometimes, I don't explain my intervention as much as I should, and I'll just (…) conduct the assessment with the team, without talking to the patient. I find it difficult because yes, the person has difficulty communicating, and there may even be doubts about their ability to understand what's happening, but (…) it's a bit like treating the person as an object: we take measures, make plans, and don't try to explain to the person what's happening." (Participant 33).

Healthcare professionals can neglect the importance of obtaining free and informed consent, as their practice paradigms are strongly rooted in a paternalism justified in their eyes. In addition, in the context where health organizations value productivity, it becomes tempting to explain things from a very specific perspective, which is faster than obtaining free and informed consent from a person who has cognitive deficits making sure they understand all the possible nuances of an intervention or choice.

This ethical issue arises even if the person clearly expresses their emotions despite cognitive deficits, as explained by participant 1:

"An elderly person, even if they have been deemed incapable, even if they have major neurocognitive disorder and cognitive impairments, if they repeatedly say: 'untie me, I'm a prisoner, untie me,' I think that carries so much weight, and we should listen to them a bit more. Listen to what they say, even if they have major neurocognitive disorder, even if they have cognitive impairments. (…) We often talk about obtaining free and informed consent for children. I feel that it's somewhat overlooked for the elderly."

Cognitive impairments become an umbrella under which caregivers shelter to justify restraint interventions and neglect the voices of elderly individuals.

Strategies can be found to respect the needs of older adults living with cognitive impairments while still allowing for a fair evaluation. Participant 8 provides an example:

"Recently, I had to assess a lady for risks in the bathroom, among other things while she was going to wash herself. But I could see that she was uncomfortable and didn't seem to understand what was going to happen, despite my explanations. So, I didn't assess her. (…) I thought to myself, 'No, she doesn't want to' I thought I would find my observations elsewhere to extrapolate what the risks would be during bathroom activities."

However, this type of adjustment can take more time for healthcare providers or reduce their confidence in their recommendations, limiting their choices to the use of alternative evaluation or intervention methods that respect patient choices.

As mentioned earlier, functional autonomy, which corresponds to a person's ability to perform activities (e.g., eating, dressing, moving) without excessive assistance or constant supervision, can be restricted by the value of safety at all costs. For example, when restraints are used to prevent falls. Additionally, the presence of symptoms deemed disruptive to the tranquility of healthcare facilities and their "smooth operation" leads healthcare professionals to use interventions that restrict functional autonomy:

"Some people with advanced major neurocognitive disorder or cognitive impairments, are still capable of propelling a wheelchair. For example, there are many people who will be able to self-propel if their feet are placed on the ground. However, cognitively, they are no longer considered of sound mind, so we think that propulsion will only serve to wander. For me, I think it's positive that the person moves because it works their legs, it allows them to engage in physical activity, and it allows them to move on their own. Often, we observe that these people who wander will be less agitated, so there are many benefits to that. On the other hand, often we have requests from the healthcare staff that when configuring the wheelchair, we don't give these people the opportunity to wander because it's disruptive, and these patients sometimes enter other people's rooms, which is disruptive, they will also touch medical equipment, which is disruptive. They may sometimes get stuck in a corner and ask for help to get out. It certainly generates more work for the staff on the floors, so we request limiting autonomy so that it doesn't disrupt the work too much." (Participant 3).

Systematically setting up barriers to patients' residual autonomy because the actions resulting from that autonomy do not align with what is deemed desirable in a standardized institutional setting is a highly prevalent and trivialized ethical issue.

Evacuated Privacy

This ethical issue is primarily experienced in residential settings. It refers to the fact that elderly individuals, especially those with cognitive deficits, are generally perceived as asexual beings. Privacy and sexual needs are evacuated or even considered inadequate:

"When it comes to sexuality, it's complex. In the minds of the healthcare providers, as soon as you're ill, you no longer have [sexual or privacy] needs." (Participant 2).

The urgency to conduct assessments and interventions takes precedence over respecting privacy, for example, when assessing the ability to bathe or when providing care in rooms where multiple patients coexist. Furthermore, in residential settings, a lack of clarity regarding which healthcare professional should address sexuality leads to confusion and gray areas when it comes to addressing this need. Sexual needs can even be perceived as inappropriate, or as symptoms of major neurocognitive disorder, and be approached as problems to be solved rather than needs to be supported:

"There's a new couple that formed in one unit. We don't know if there was a sexual relationship, but they were both found in the same bed. (…) The man still had his wife. The woman no longer had a spouse. (…) When it comes to sexuality, it's complex. In the minds of the caregivers, it was a crisis to be resolved. (…) We worked with both families. One family was very uncomfortable, so we put in place an intervention plan to supervise and limit contact between the two residents." (Participant 7).

For healthcare providers who receive little or no specific training in supporting sexuality, it seems difficult to understand how to intervene. When the elderly individual has a cognitive deficit, it further complicates the intervention, making it even easier to slide into control measures rather than support measures. Also, here again, it is often the professional teams or families who decide, rather than the older adults themselves, who are faced with decisions made by others for them which are literally imposed on them for supposedly their own good.

Restricted Access to Care

Older adults with cognitive deficits may not be considered equal to those without such deficits when it comes to access to care, notably concerning access to certain types of housing or rehabilitation programs. In fact, these programs are designed with the aim of ensuring their success. Inclusion criteria for these programs, for instance, are restrictive to avoid including patients who might risk "failing" in the treatment and negatively affecting the success statistics of the interventions. As a result, patients with cognitive deficits that could influence their attendance and chances of success may not be admitted. One participant even gives an example of restricted access to interventions essential for survival:

"Recently, I had a case where I had to assess whether the patient was a candidate for a heart transplant. My manager explained the situation as follows: 'If the lady has cognitive problems, she is not a candidate'. (...) I don't understand why we would let the lady die from heart failure for the sole reason that she has cognitive deficits." (Participant 18).

Discussion

This article aimed to explore the ethical challenges faced by older adults with cognitive deficits when receiving care. The insights shared by the occupational therapists involved in our study helped identify four primary ethical issues.

Firstly, the dominance of safety at the expense of values related to health, well-being, and freedom emerged as a problematic element in the care of older adults with cognitive deficits. A paternalistic approach by healthcare teams places older adults in a position where they must be overly protected, regardless of their quality of life and their remain abilities. It is as if the onset of cognitive deficits marks a turning point at which the person is no longer considered in their humanity but rather perceived as a fragile object to be preserved. In the culture of "caring for" it seems that it is better to constrain and protect than to support by tolerating risk, especially if it is believed that taking that risk cannot be done in an informed manner due to the presence of cognitive deficits. At the very least, this is the attitude that still seems to pervade the organizational cultures in the continuum of healthcare, which can lead to situations of organizational abuse. This emphasis on safety at all costs resembles the concept of life at all costs, a concept widely discussed in the literature on therapeutic obstinacy. Notably, our results related to safety concerns about nutrition echo concerns about the means used to extend the lives of the elderly at any cost [25,26]. Moreover, clinical, and ethical reflections have been initiated in recent years regarding palliative care for older adults with major neurocognitive disorder [27-28]. In particular, Duzan and Fouassier emphasize that questions surrounding end-of-life care for patients with major neurocognitive disorder are crucial and should prompt a reevaluation of the criteria upon which healthcare team’s base palliative care. According to them, it is essential to "know how to recognize the advanced forms of major neurocognitive disorder and their prognosis to be able to match the level of care to these characteristics and avoid therapeutic obstinacy or, conversely, abandonment".

Furthermore, the disregarded autonomy, both in terms of decision-making and functionality, is another highlighted issue in our research. This problem is rooted in the desire of care settings to control the decision-making autonomy of people with major neurocognitive disorder, once again in the rhetoric of protection and safety. It seems that the missteps by healthcare professionals originate, in part, from the difficulty of distinguishing between what is deemed best by healthcare organizations imbued with normalized ageism and what is best for the human being seeking care and support. Rigaud and Latour [29] have explored this issue, drawing on the work of Appelbaum, Dworkin, and Jaworska. They emphasize that before seeking answers to questions about the autonomy of elderly people living with major neurocognitive disorder, it is necessary to be attentive to how these questions are framed. While decisional autonomy and functional autonomy are closely related, it is important to question the relevance of this conceptual distinction. Currently, the conceptual distinction is rarely made in healthcare settings, and presumed infringements on decisional autonomy are often considered dependent on limitations in functional autonomy. Furthermore, the national ethics committee on aging [30] highlights that the issue of respecting the autonomy of people with cognitive deficits is prone to deviations when "temporal or situational pressure, the need to obtain consent for an intervention is lacking because a quick decision is needed, because a fast intervention is required, because quick protection is needed, and because time is short" (p. 8), as indeed highlighted in our study. Rigaux's [31] thoughts on a concept of "major neurocognitive disorder-friendly" autonomy appear to be a good conceptual starting point to shift the "responsibility" for maintaining the autonomy of a person with major neurocognitive disorder from the individual to the environment. His work emphasizes, "Over the centuries, the importance of the value of autonomy has not diminished, even though its content has varied over time. A critical examination of philosophical and medico-social literature has shown that the different meanings ascribed to autonomy can be organized around two poles. In the canonical pole, autonomy is a question of skills internal to the subject (rationality, reflexivity, memory), where others appear as threats. This conception excludes major neurocognitive disorder patients from access to autonomy in the short or long term. The relational pole considers it essential to question the external conditions of autonomy: the relationships and organizations in which the person is embedded, the policies on which they depend, do they provide an opportunity to exercise their autonomy? From this perspective, others are not primarily a threat but potentially a resource for achieving autonomy. Therefore, the burden of proving the possibility of access to autonomy shifts from the person to those around them and to the institutions and policies that concern them". Organizational transformation in healthcare settings that encourage compromises to balance risk and autonomy should be pursued. To achieve this, healthcare settings should reconsider their organizational cultures, which for the time being require professionals to perform tasks primarily associated with medical procedures rather than assistance tasks. In geriatric care, "the work of constraint represents a significant part of the professionals' activity (...) and is part of the routine of geriatric treatment. (...) frontline healthcare professionals, those most involved in the daily management of patients and especially in managing disruptive behaviors, explicitly highlight the necessity they face in obtaining the patients' bodies' availability for treatment, within the time frames that allow the service to function smoothly" [32]. Obtaining the availability of bodies for action should no longer be the goal of professionals in determining whether they have "done their job well", "achieved the goals of care" or "reduced waiting lists." The quality of care provided, and the relationship created with the patient and their family should become central indicators for assessing adequate medical and therapeutic support. Really listening to seniors' wishes, act in accordance with their desires, should be central to this measure of the quality of care. However, institutions should be willing to relinquish control, which is not yet an established practice.

The questions surrounding safety, autonomy, and capacity for elderly people with cognitive deficits are complex and interwoven with the already complex considerations of these individuals' consent. While we do not expect elderly people with significant cognitive deficits to provide clear and unequivocal consent for the assessments and interventions they receive, it appears that a margin of maneuver that allows sensitivity to signs of refusal or discomfort would be beneficial, not only to the well-being of the elderly but also to the well-being of the professionals caring for them. The words of Gzil [33] seem to accurately express how this margin of maneuver would be favorable to kindness in care: "Instead of trying to respect autonomy that is no longer-or that is only a shadow of itself - and trying to find a consent that patients can often no longer give, and instead of increasing their anxiety by wanting to empower them absolutely, would it not be better here to reason based on other principles? Should we not, in Alzheimer's disease for example, refocus the debate on the values of non-maleficence, justice or dignity?” In doing so, we could reduce or even eliminate the epistemic injustices too often experienced by many older adults. These injustices are notably linked to unfairly denying the ability of older people to take part in decisions that concern them in the first place.

Limitations and Strengths of the Study

The study involved many occupational therapists with both clinical and managerial experience in the healthcare sector, and they came from various practice settings. These factors contributed to the richness of the results obtained. However, it would have been favorable to include the older adults themselves in the research. By not doing so, we contribute to the exclusion dynamics we critique in this text [34-47].

Conclusion

The four categories of ethical issues outlined in this article show that there is a significant risk of healthcare teams shifting from a client-centered approach to an autocratic posture when dealing with cognitive deficits in elderly patients. In addition to paternalism and ageism, which affect many older adults within the healthcare system, the presence of cognitive deficits places older adults at the center of an even more complex oppressive intersection, to which ableism is added, which corresponds to a system of oppression based on disabilities. Following this view, a hierarchy is proposed whereby people with disabilities are unfairly inferior and denied of their remaining abilities and strengths. Healthcare professionals, often uncomfortable with the systems and organizational cultures in which they must operate, could be key players in effecting change. This battle has already begun in Canada, as conceptual and care models are being developed to prioritize patients in interventions. Professional associations are mobilizing in this direction. It is crucial to continue this struggle.

References

- Organisation mondiale de la Santé (2016) La démence - Aide-mémoire [en ligne]. Genève (Suisse): Organisation mondiale de la Santé. Sur Internet.

- Gouvernement du Canada (2022) Démence: Vue d’ensemble. Repéré à. Retrieved In Online.

- Agence de la santé publique du Canada (2014) Organismes caritatifs neurologiques du Canada. Établir les connexions: Mieux comprendre les affections neurologiques au Canada. Ottawa (Ont.): Agence de la santé publique du Canada. P: 1-6.

- Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG (2015) Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of major neurocognitive disorder. BMJ, 350: 369.

- Emmady PD, Schoo C, Tadi P (2022) Major neurocognitive disorder (dementia). In StatPearls Publishing.

- Khanassov V, Rojas-Rozo L, Sourial R, Yang XQ, Vedel I (2021) Needs of patients with dementia and their caregivers in primary care: lessons learned from the Alzheimer plan of Quebec. BMC Fam Pract. 22: 186.

- Rotermann M (2015) High use of acute care hospital services at ages 50 and older. Health Reports. 82-003-X.

- Cruise CE, Lashewicz BM (2022) Dementia and dignity of identity: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Dementia, 21: 1233-1249.

- Hein C (2009) Prise en charge de la démence chez les sujets âgés vulnérables. La personne âgée fragile. 105-110.

- Heggestad AKT, Nortvedt P, Slettebø Å (2013) ‘Like a prison without bars’ Dementia and experiences of dignity. Nursing Ethics, 20: 881-892.

- Monod S, Sautebin A (2009) Vieillir et devenir vulnérable, Rev Med Suisse. 5: 2353-2357.

- Austin A, O’Neill J, Skevington S (2016) Dementia, Vulnerability and Well-being: Living Well with Dementia Together. A report from the University of Manchester for Age UK and the Manchester Institute of Collaborative Research on Ageing. Manchester, UK. PP: 50.

- Dong XQ, Chen R, Simon MA (2014) Elder abuse and major neurocognitive disorder: a review of the research and health policy. Health Affairs. 33: 642-649.

- Parmar D (2021) Ethical aspects of informed consent in dementia. Global Bioethics Enquiry Journal, 9: 42-45.

- Lacour C (2009) La personne âgée vulnérable: entre autonomie et protection. Gérontologie et société. 32: 187-201.

- Gove D (2012) Éthique de la recherche sur les démences. Alzheimer, éthique et société. Toulouse: Érès. P: 377-390.

- Lord M-M, Ruest M, Drolet M-J, Viscogliosi C, Pinard C (2023) Elder Organisational Abuse in Long-Term Care Homes: an Ecological Perspective. Journal of Aging and Social Change. 13: 61-85.

- Barnitt R (1998) Ethical dilemmas in occupational therapy and physical therapy. Journal of Medical Ethics, 24: 193-199.

- Bushby K, Chan J, Druif S, Ho K, Kinsella EA (2015) Ethical tensions in occupational therapy practice. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 78: 212-221.

- Drolet M-J, Maclure J (2016) Les enjeux éthiques de la pratique de l’ergothérapie. Approches inductives, 3: 166-196.

- Giorgi A (1997) The Theory, Practice, and Evaluation of the Phenomenological Method as a Qualitative Research Procedure. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology. 28: 235-260.

- Husserl E (1999) The Train of Thoughts in the Lectures. In Perspectives on Philosophy of Science in Nursing, edited by Dans E. C. Polifroni, and M. Welch, 1-12. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott.

- Swisher, L. L. D., Arslanian, L. E., & Davis, C. M. (2005). The realm-individual process-situation (RIPS) model of ethical decision-making. HPA Ressource, 5(3), 3-8.

- Corbière M, Larivière N (2020) Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods, 2nd edition: In research in human, social and health sciences. PUQ. PP: 880.

- Cohen-Mansfield J (2021) The rights of persons with major neurocognitive disorder and their meanings. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 22: 1381-1385.

- Podgorica N, Flatscher-Thöni M, Deufert D, Siebert U, Ganner M (2021) A systematic review of ethical and legal issues in elder care. Nursing ethics, 28: 895-910.

- Duzan B, Fouassier P (2011) Maladie d’Alzheimer et fin de vie: aspects évolutifs et stratégies thérapeutiques. Médecine Palliative. 10: 230-244.

- Pageau F (2020) La responsabilité de protéger les personnes âgées atteintes de démence. Manifeste. Presses de l'Université Laval. PP: 66.

- Ligonnet F (2022) Éthique et soin: La question de l’euthanasie à l’épreuve de la maladie d’Alzheimer. Jusqu’à la mort accompagner la vie, 2: 111-118.

- Gzil F, Rigaud AS, Latour F (2008) Démence, autonomie et compétence. Éthique publique. Revue internationale d’éthique sociétale et gouvernementale, 10.

- Comité national d’éthique sur le vieillissement (2022) Le respect de l’autonomie et la securite des personnes les plus agees a domicile : un equilibre fragile dans le parcours de vie a domicile.

- Rigaux N (2011) Autonomie et démence. Geriatrie et psychologie neuropsychiatrie du vieillissement, 9: 107-115.

- Hurard LL (2013) Faire face aux comportements perturbants: le travail de contrainte en milieu hospitalier gériatrique. Sociologie du travail, 55: 279-301.

- Gzil F (2009) Respecter une autonomie fragilisée par la maladie. Presses Universitaires de France. PP: 163-212.

- Drolet M-J (2022). Repérer et combattre le capacitisme, le sanisme et le suicidisme en santé. Revue canadienne de bioéthique, 5: 89-93.

- Drolet MJ (2020) Conflits de loyautes multiples en ergotherapie: quatre defis contemporains de l’ergotherapeute. In J. Centeno, L. Begin, & L. Langlois (Eds.), Les loyautes multiples: Mal-etre au travail et enjeux ethiques, PP: 39-77.

- Fortin M, Stewart M (2021) Mise en œuvre de soins intégrés centrés sur le patient pour des problèmes chroniques multiples: Référentiel éclairé par des données probantes. Canadian Family Physician, 67: 242-245.

- Pétré B, Louis G, Voz B, Berkesse A, Flora L (2020) Patient partenaire: de la pratique à la recherche. Santé publique, 32: 371-374.

- Moulias S, Berrut G, Salles N, Aquino JP, Guérin O, et al. (2021) Manifeste pour le droit des personnes âgées. Gériatrie et Psychologie Neuropsychiatrie du Vieillissement, 19: 9-19.

- Lalancette M, Drolet MJ, Caty MÈ (2020) Advocacy et nouveaux modes managériaux: le rôle politique de deux ordres professionnels de la santé. Communiquer. Revue de communication sociale et publique, 29: 39-60.

- Durivage P, Pott M, Van Pevenage I, Blamoutier M, Freitas Z (2021) L’accompagnement des personnes âgées en fin de vie à domicile par les travailleurs sociaux au Québec et en Suisse: faut-il une innovation sociale pour créer l’espace de discussions de fin de vie?. Cahiers francophones de soins palliatifs. 21: 89-101.

- Bérubé P (2023) Entre disability studies et études sur le handicap: 40 ans d’enjeux d’accès, de traduction et d’éducation. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 12: 177-202.

- Beudaert A, Nau JP (2021) La vulnérabilité des consommateurs en situation de handicap: les apports d’une prise en compte du temps. Recherche et Applications en Marketing (French Edition), 36: 3-26.

- Martineau I, Ummel D, Fortin G (2023) Quelques réflexions éthiques autour du respect de l’autonomie et du consentement, dans le contexte de l’aide médicale à mourir en situation de handicap. Intervention, 156: 85-96.

- Seitz DP, Gill SS, Gruneir A, Austin PC, Anderson GM, et al. (2014) Effects of major neurocognitive disorder on postoperative outcomes of older adults with hip fractures: a population-based study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 15: 334-341.

- Stefani L (2008) Problèmes éthiques soulevés par la prise en charge thérapeutique des patients âgés déments atteints de cancer. InfoKara. 23: 83-90.

- Strubel D, Hoffet-Guillo F (2004) La fin de vie du dément. Psychologie & NeuroPsychiatrie du vieillissement, 2: 197-202.

Citation: Lord M-M, Viscogliosi C, Drolet M-J (2023) Ethical Challenges Experienced by Older Adults with Cognitive Impairments in the Continuum of Health and Social Services: Examples Drawn From the Professional Experiences of Occupational Therapists. J Gerontol Geriatr Med 9: 193.

Copyright: © 2023 Marie-Michèle Lord, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.