Evaluating a Holistic and Collaborative Model of Military Health: Clients’ Perspectives

*Corresponding Author(s):

Sheila CannonDepartment Of Nursing, College Of Arts And Sciences , 1200 Murchison Road, Fayetteville-28301-4252, North Carolina, United States

Tel:+1 9106721105,

Email:scannon3@uncfsu.edu

Abstract

Healthcare is seeing an increasing number of clients seeking Complementary and Alternative (CAM) therapies for the treatment of mental and physical healthcare need. A University in Southeastern North Carolina uses a unique interprofessional team-based practice model that embodies complementary and alternative approaches to the psychosocial health of military families. Military affiliated clients (177) completed a Client Satisfaction feedback survey, which determined if holistic services provided met their physical and mental health needs. Survey findings concluded that the clients’ health status in most areas improved. Of the 175 who responded to the survey item, 87% (n=154) indicated that they felt “much better than before” coming to the Institute. Qualitative measures revealed descriptors of “awesome”, amazing”, “wonderful” and “a blessing”. Of their overall experience at the Institute. This holistic model has the capacity to inform and advance military health through the use of CAM treatment modalities for chronic pain, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, using the complement and collaboration of interprofessional teams.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

A conventional medicinal approach is not enough to address the visible and invisible war wounds of the nation’s veterans or their families. Often these war wounds disguise themselves as multi-somatic symptoms, difficult to diagnose and treat problems. These problems of physical and/or psychological pain and disability require a combination of collaborative and holistic approaches to treatment necessary to enhance healing in this vulnerable population.

BACKGROUND

Military health

A study conducted by Hoge, Castro, and Messer [6] reported that 17% of soldiers returning from Iraq screened positive for PTSD, depression, and generalized anxiety, which was nearly twice the rate (9.3%) observed among soldiers before deployment. An estimated 37% of Iraq war veterans accessed mental health services in the year after returning from home [7]. Another concern is that approximately 3% of active duty service members have attempted suicide during their military career [8]. Estimates for service members who conceal their suicidal thoughts and who attempted suicide (77.9%) is greater compared to those who died by suicide (65.84%) [9]. These staggering statistics of psychological distress alone challenges the need for adequate resources to meet mental health concerns and places more responsibility on the support of communities to do so.

Holistic approach

Health care is seeing an increasing number of clients seeking Complementary and Alternative (CAM) therapies for the treatment of their mental and physical health care needs [10,13]. In fact, military personnel use alternative medicine and stress reduction therapies more often than the general public [14]. Further, the US Army increasingly supports holistic pain management for wounded warriors and is changing its narcotic focused approach to pain management [15]. Moreover, the Army Pain Management Task force has called for the use of integrative and alternative measures such as acupuncture, meditation, cognitive behavioral therapies, in combination with conventional medicine for a comprehensive approach to care [16,17].

Acupuncture has demonstrated success in relieving tension headaches and migraines that can occur due to stress and chronic pain conditions Vickers, Cronin, & Maschino, [18]. A study reported by McPherson and Schwenka [13] of 291 soldiers, veterans, and spouses revealed that 81% use one or more CAM therapies, with massage ranking high on utilization. Inaddition, in this sample, pain, stress, and anxiety were the most common reasons for selected CAM. Most endorsed their use of these services if offered at the medical treatment facility (69%) or would self-pay (24%), whereas 44% were undecided.

A study released by the National Center for Health Statistics [19] showed evidence that out of the 31,000 adult respondents who were surveyed, 62% used some form of CAM, especially when mega-vitamin and prayer therapy were included as homeopathic approaches. However, with exclusion, only 36% endorsed its use [10]. Some of the common CAM therapies that were reported were mind-body relaxation techniques, massage, chiropractic, acupuncture, herbs and supplements.

Interprofessional collaborative practice model

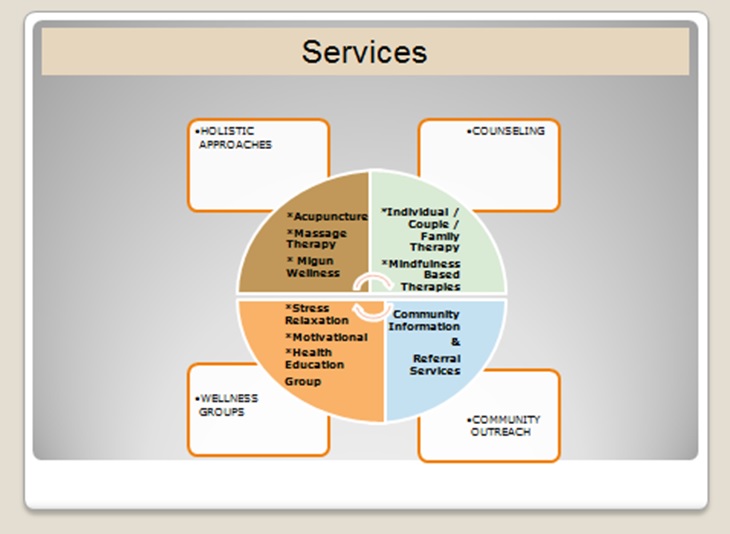

The overarching need for interprofessional collaboration is the notion that teams accomplish more together than they do separately (The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation (JMF), [23]; National League of Nursing (NLN), [24]). A collaborative team approach leads to improved patient outcomes and satisfaction and increased health professionals’ efficiency and job satisfaction [25]. The model of such partnerships depicted in figure 1 underscores our efforts toward an interprofessional team-based approach that embodies psychosocial health and wellness of military families. This article showcases the results of a client feedback survey of a viable HRSA funded interprofessional collaboration model of clinical practice. The practice has a complement of licensed psychologists, social workers, nurse practitioners, massage therapists, interdisciplinary students, and an acupuncturist. This focused-holistic approach to behavioral health included complementary and alternative therapies as treatment options for chronic pain, PTSD, and other co-morbidities [26,27].

Figure 1: A Holistic Collaborative Model of Military Health.

Figure 1: A Holistic Collaborative Model of Military Health.Setting

CI-PEP, spearheaded by nursing faculty, has offered free integrated and holistic services to 750-plus military personnel, veterans, and their families with an emphasis on pain management, bio-behavioral and psychosocial wellness, veteran women’s health, as well as family integration. Treatment modalities offered include CAM (massage, acupuncture/acupressure, and migun wellness), individual and couples counseling, support groups (mindfulness based therapies), health education, and coordination of referrals in a military and veteran culturally-informed environment. The migun thermal massage bed used for services offers the effects of acupressure, acupuncture, heat-therapy (moxibustion), chiropractic, and massage. This FDA approved physical therapy thermal massage system provides 30-45 minutes of pure relaxation and meditation by uniquely integrating traditional Eastern medicine with Western technology to provide massage like no other.

CI-PEP is open two days per week and has a robust history of averaging 45-55 clients per two days for all services. Additionally, 104 couples receive services together, which denote our efforts toward psychosocial wellness, family reintegration and stability around deployment issues. CI-PEP is state approved as a child care drop-in center, further supporting the family and making it easier to receive these services.

CI-PEP is supported by a dynamic interprofessional team of licensed psychologists, nurse practitioners, licensed social workers, massage therapists, an acupuncturist, and grounded by an active advisory board representing community and military leaders. CI-PEP also provides a supervised interprofessional clinical training site for undergraduate and graduate students majoring in nursing, social work, and counseling psychology. It is designed to graduate interprofessional students who are capable of providing high-quality well-coordinated care through an Interprofessional Collaborative Practice (IPCP) model of education, with educational outcomes achieved to meet the biopsychosocial health care needs of diverse populations, including military families. CI-PEP provides community support services for service members and their families and offers an opportunity to evaluate the efficacy of this interprofessional, innovative and collaborative practice model of military health.

Clients are accepted as walk-ins or scheduled appointments and can self-select any services identified in the model. Counseling services and treatment modalities, including mindfulness based therapies, are led by licensed psychologists and intern students from the University’s counseling Psychology Department. Holistic approaches are assessed by a fourth generation Acupuncturist holding a masters and doctoral degrees in oriental medicine. The Acupuncturist is a licensed independent contractor who has years of expertise in treating acute and chronic pain and offered multiple treatments for pain and skin revitalization such as the five-element approach and the Korean four-needle technique. Massage therapy is often the main entry to other services and provided by two licensed massage therapists, one being a registered nurse. Psychoeducational groups, facilitated by a psychiatric nurse practitioner and nursing students are also offered to clients. Licensed clinical social workers and social work students serve as the bridge to community referrals and outreach. They are also instrumental in providing case management for homeless veterans and facilitate veteran peer support through locally-affiliated veteran support agencies.

METHODOLOGY

Participants

| Variables | (Frequency / Percent) | |

| Demographic | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 102 | 57.6 |

| Male | 75 | 42.3 |

| Transgender | 0 | 0 |

| Age Range | ||

| 18-25 | 0 | 0 |

| 26-34 | 43 | 24 |

| 35-44 | 51 | 29 |

| 45-54 | 42 | 24 |

| 55-64 | 17 | 10 |

| 65- older | 24 | 13 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 17 | 10 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 9 | 5 |

| Asian | 9 | 5 |

| Black / African-American | 80 | 45 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific | 0 | 0 |

| White / Caucasian | 62 | 35 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/living with partner | 149 | 84.1 |

| Divorced/separated/never married | 22 | 12.4 |

| Widowed | 4 | 2.26 |

| Never married | 2 | 1.13 |

| Duty Status | ||

| Active Duty (All Branches) | 53 | 30 |

| Active Duty Spouse (All Branches) | 28 | 16 |

| Veterans (All Branches) | 78 | 44 |

| Veteran Spouses (All Branches) | 12 | 7 |

| Missing / Incomplete Data | 6 | 3.4 |

| Perceived Health Status (Before Services) | ||

| Excellent or very good | 77 | 44 |

| Good | 84 | 47 |

| Fair or Poor | 16 | 9 |

Procedure

| Experience | Rating | |||

| Overall, how would you rate the service you Received today? |

Excellent (93%) |

Good (6.2%) |

Okay (0%) |

Poor (0%) |

| Overall, how would you Rate the difference in your physical or mental health as a result of the service you received today? (n=175) |

I feel much better than before (87%) |

I feel about the same as before (10.2%) |

I feel worse than before (0%) |

Unsure (1.7%) |

| How well did the service meet your expectations? (n=174) | Exceeded Expectations (70.1%) |

Met Expectations (28.2%) |

Did Not Meet Expectations (0%) |

|

| 5. Do you plan to come back to the Institute for the same service or Different service? (n=175) |

Same Service (88.7%) |

Different Service If so what service(s) (Acupuncture, Counseling, Migun Wellness or Massage) |

Unsure (1.1%) |

Do not plan to return (0%) |

| How likely will your visits at the Institute reduce the number of visits you typically make to your primary care physician? |

Very likely (57%) |

Somewhat Likely (24.3%) |

Not at All Likely (5.6%) |

The services are different (13%) |

| How likely will you recommend the Institute to others? (N=176) | Very Likely (97.7%) |

Somewhat Likely (1.7%) |

Not at All Likely (0%) |

Unsure (0%) |

Data analysis

Analyses of quantitative data consisted primarily of descriptive statistics represented by frequencies of participant responses. Qualitative data were conducted via content analysis for emerging themes that explained or provided greater insight into the meaning of the survey frequencies. The program evaluator and a team of quality metric staff independently coded the repetitive emerging themes. The coders reviewed with each other their themes and reached a consensus where there were differences. Only themes for which a consensus was reached were included in the final data. This procedure was used to ensure a degree of interrater reliability.

RESULTS

Qualitative findings

“Professional”, “personable”, “informative”, “listens to me”, “courteous”, and “friendly and accommodating”.

The outcome of experience:Comments more specific to the results of the experience included:

- “Thank you for the emotional transition”.

- “I feel like a new person”.

- “My joints and muscles feel a lot better”.

- “The [provider] goes above and beyond”. “Great relaxed feeling”.

- “The Migun services are helpful for chronic pain”.

- “Thank you for being here”.

- “Please find funding so you can stay. You are a blessing”.

- “Less time between services”. (massage therapy)

- “The Migun bed [was] just a little rough on the tailbone”.

- “No signs on the building, bad directions from the police department”.

DISCUSSION

Our lived experience with treating military families are consistent with other studies that support the need to consider alternative forms of mental health delivery in this population. It is imperative that healthcare options are available that remove stigmatization and other barriers to seeking health care [6,9]. A belief that holds true for our Institute, as well as other researchers is the closer the collaboration amongst healthcare providers is, the more efficient the team is in diminishing psychological and physical distress of anxiety, PTSD, and pain and suffering for military personnel and families [3].

LIMITATIONS

IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

REFERENCES

- Gibbons SW, Hickling EJ, Watts DD (2012) Combat stressors and post-traumatic stress in deployed military healthcare professionals: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs 68: 3-21.

- Kearney DJ, Simpson TL (2015) Broadening the Approach to Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and the Consequences of Trauma. JAMA 314: 453-455.

- Howard MD, Cox RP (2008) Collaborative intervention: a model for coordinated treatment of mental health issues within a ground combat unit. Mil Med 173: 339-348.

- Howard MD, Cox RP (2008) Collaborative intervention: a model for coordinated treatment of mental health issues within a ground combat unit. Mil Med 173: 339-348.

- Steenkamp MM, Litz BT, Hoge CW, Marmar CR (2015) Psychotherapy for Military-Related PTSD: A Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA 314: 489-500.

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, et al. (2004) Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med 351: 13-22.

- Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS (2006) Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 295: 1023-1032.

- Kinn JT, Luxton DD, Reger MA, Gahm GA, Skopp NA, et al. (2011) Department of Defense Suicide Event Report (DoDSER) Calendar Year 2010.

- Jobes DA, Lento R, Brazaitis K (2012) An evidenced-based clinical approach to suicide prevention in the Department of Defense: The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS). Military Psychology 24: 604-623.

- Zahourek RP (2008) Integrative holism in psychiatric-mental health nursing. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 46: 31-37.

- Oranye NO (2015) A model for equalizing access to knowledge and use of medicine - orthodox, complementary, alternative, or integrated medicine. J Altern Complement Integr Med 1: 1-3.

- Institute of Medicine (2011) Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care education, and research. National Academies Press, Washington, DC, USA.

- McPherson F, Schwenka MA (2004) Use of complementary and alternative therapies among active duty soldiers, military retirees, and family members at a military hospital. Mil Med 169: 354-357.

- Nielsen A, MacPherson H, Alraek T (2014) Acupuncture for military personnel health and performance. J Altern Complement Med 20: 417-418.

- Buckenmaier C 3rd, Schoomaker E (2014) Patients’ use of active self-care complementary and integrative medicine in their management of chronic pain symptoms. Pain Med 15: 7-8.

- Archer S (2011) US Army Supports Holistic Pain Management. IDEA Health & Fitness Association 8.

- Schoomaker EB (2010) The Pain Management Task Force. STAND-TO, US Army, USA.

- Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, Lewith G, MacPherson H, et al. (2012) Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 1444-1453.

- Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL (2004) Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data 27: 1-19.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN)) (2012) Quality & Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN). American Association of Colleges of Nursing, Washington, DC, USA.

- College of Nursing of Ontario (2008) Interprofessional collaboration among Health College and professions - Submission to the Health Professions Regulatory Advisory Council. College of Nursing of Ontario, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- Engel CC, Oxman T, Yamamoto MC, Gould D, Barry S, et al. (2008) RESPECT-Mil: feasibility of a systems-level collaborative care approach to depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in military primary care. Military Medicine 173: 935-940.

- The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation (2009) Developing a strong primary care workforce. The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, New York, USA.

- National League for Nurses (2012) Innovation in nursing education: a call to reform. National League for Nurses, Washington, DC, USA.

- The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation (2010) Educating Nursing, and Physicians: Toward New Horizons - Advancing Inter-professional Education in Academic Health Centers, The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, Palo Alto, California, USA.

- Arhin AO, Gallop K, Mann J, Cannon S, Tran K, et al. (2015) Acupuncture as a Treatment Option in Treating Posttraumatic Stress Disorder-Related Tinnitus in War Veterans: A Case Presentation. J Holist Nurs.

- Hughes RG (2008) Nurses at the “sharp end” of patient care. In: Hughes RG (ed.). Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses (Chapter 2). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Washington, DC, USA.

Citation: Cannon S, Arhin AO, Thomas GL, Hodges S (2016) Evaluating a Holistic and Collaborative Model of Military Health: Clients’ Perspectives. J Altern Complement Integr Med 2: 007.

Copyright: © 2016 Sheila Cannon, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.