Excessive Alcohol Use and Its Negative Consequences among Women of Child Bearing Age in Africa: A Systematic Review

*Corresponding Author(s):

Apophia AgiresaasiDepartment Of Makerere College Of Health Sciences, Uganda

Tel:+256 776626187,

Email:agiresaasi@gmail.com

Abstract

Research examining excessive alcohol use among women on the continent is scanty. The study sought to review literature on the prevalence of various forms of excessive alcohol use among women in the reproductive age group in Africa. A literature search of several databases for relevant literature was undertaken. Published studies that reported alcohol exposure for women aged 15-49 were included.

Frequent alcohol consumption ranged from 3.9% in Tanzania to 34.9% in Ghana. Heavy drinking ranged from 0.9% in Mauritius to 25.4% in Congo. Harmful alcohol use, hazardous drinking and alcohol dependence were mostly reported in South Africa and Lesotho and ranged from to 1.1 to 13%. The study found strong evidence to link the various forms of excessive alcohol use to FAEE, HIV acquisition among others. Excessive alcohol use among women aged 15-49 in Africa varies from country to country with diverse consequences. Binge drinking is particularly common.

Introduction

Excessive alcohol use in this article refers to the different patterns of alcohol use which include binge drinking, frequent alcohol use, heavy drinking, harmful alcohol use, hazardous drinking, alcohol dependence and risky drinking. Various scholars have defined these terms.

Binge drinking is defined as drinking 70 g (men) or 56 g (women) or 4 drinks in about two hours [1]. Dependent use is a cluster of physiological, behavioural, and cognitive\phenomenon in which the use of alcohol takes on a much higher priority for the individual than other behaviours. These phenomena include increased desire to use alcohol with impaired control, persistence use despite harmful consequences, higher priority given to alcohol use than any other obligations, increased alcohol and a physical withdrawal reaction when alcohol use is Discontinued [2]. Frequent Alcohol Consumption is defined as drinking three times a week [3]. Heavy Alcohol Consumption is drinking 5 or more drinks on the same occasion on each of 5 or more days in the past 30 days [4]. Hazardous alcohol use is the use of alcohol that will probably lead to harmful consequences to the user, either to dysfunction or to harm similar to the idea of risky behaviour [5]. Harmful drinking is defined as a pattern of alcohol consumption causing health problems directly related to alcohol [6].

It should be noted that some studies define these terms a little differently. The WHO Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) has been used to define AUDIT score of 20 and above as problem drinking or alcohol dependence. AUDIT cut off score of 5 or more as hazardous/harmful drinking.

Excessive alcohol use is a major public health concern across the world. It has been linked to morbidity and mortality from a range of both social and physical illnesses [7]. It is also a component cause of several diseases and injury conditions as described in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) 10th Revision [8].

Women are more likely to suffer the consequences of excessive alcohol use than men due to lower body weight, a higher proportion of body fat, smaller liver capacity to metabolize alcohol which together contributes to women achieving higher blood alcohol concentrations for the same amount of alcohol intake [9,10]. Women are also affected by interpersonal violence and risky sexual behaviour as a result of the drinking problems and drinking behaviour of male partners [11].

The effects of alcohol and burden of disease has been greatest in developing countries around the world [8]. During pregnancy, alcohol use increases the risk of pre- term births (PTB), stillbirths, low birth weight (LBW) several birth defects and developmental disabilities known as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) [12]. It is also associated with early childhood leukaemia [13], infant cleft palate and infertility in males and females [14,15] . Excessive alcohol use has been reported to be more harmful to the growing foetus as compared to low level alcohol use [16]. Research has established the presence of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in South Africa [17]. This data in other countries on the continent is sparse however.

Women’s drinking affects the community and families more than men’s drinking given their gender roles and the tendency to hide drinking problems , more needs to be done to address the consequences of alcohol use on the continent before they escalate given the aggressive marketing that targets women [18,19] .The adoption of the WHO Global Strategy and WHO Regional Strategy (for Africa) to reduce the harmful use of alcohol in 2010 and the WHO Global Action plan for the prevention and control of non-Communicable diseases in 2013 set the stage for addressing alcohol use and its effects in Africa. But not much has been done since to stem the tide [20] . Yet several studies have documented a change towards a “public, binge drinking culture over the weekends”, leading to important health, social and development consequences, and have underlined the need to protect the population in general, and women and children in particular, from alcohol-related harms [21, 22].

It is important to understand the levels and patterns of excessive alcohol use among women on the continent. Such understanding will be useful in making recommendations for interventions meant to reduce alcohol use and its effects.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

This systematic review considered studies conducted in the 54 countries that constitute Africa that assessed excessive alcohol use among women aged 15-49. The following inclusion criteria was used:

- Various forms of Alcohol use were investigated.

- Negative consequences associated with alcohol use were investigated.

- Recruitment of study participants was either population based or took place in a health care environment (antenatal care clinic, ultra sound clinic, delivery clinic, STI clinic, TB treatment clinic)

- Data was collected between the period 1996 -2019

- The study was published in a scientific peer reviewed journal in English in the last two decades (1996 -2019).

This standardised inclusion criteria was instrumental in facilitating comparison of studies and results to ensure that methodological differences do not result in differing outcomes.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded a few studies that

- Did not investigate alcohol prevalence/incidence

- Did not document frequency and quantity of alcohol consumed

- Studies conducted outside Africa

- Studies that did not conduct original empirical data

Search strategy

To obtain studies for the review, a literature search of studies published from January 1996 to December 2019 was undertaken. A primary research was conducted to identify all related primary research in English from all relevant databases and journal collections including google scholar, Sage Online Journals, Taylor and Francis Online, Wiley Online Library, Project Muse JSTOR (Journal Storage) by using the text words such as (“alcohol burden” OR “alcohol negative effects”) AND (“alcohol prevalence” OR “alcohol use by women in Africa”) AND (“alcoholconsumption by women” OR “Africa”). We also manually searched the google search engine by interchanging the text words with each other. The authors were assisted by an experienced librarian in searching these data bases. The search was limited to articles either published in English after 1995.

Search words

The following search words were used. Alcohol Use, Alcohol Consumption, Prevalence, Alcohol Effects, Alcohol Burden, Alcohol Negative Effects, Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, East Africa, Algiers, Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Democratic Republic Of The Congo, Republic Of The Congo, Cotd’voire, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bisau, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome, Senegal, Seycheles, Sierra- Leone, South Africa, Sudan, South Sudan, Swaziland (Eswatini), Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia And Zimbabwe.

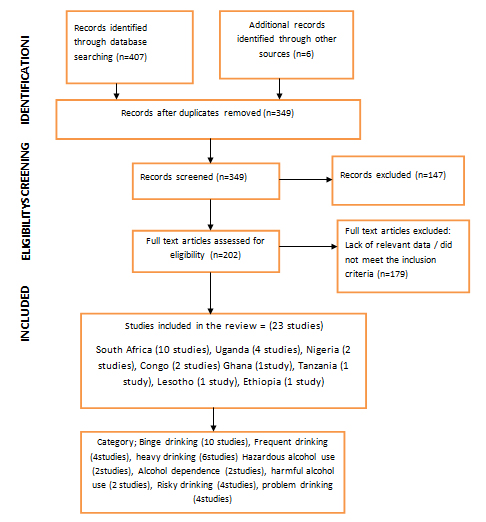

The database yielded 407 Potential articles. Six More articles were obtained from references. These were screened against the inclusion criteria. Only 23 studies contained relevant data and were retained for data extraction. These articles were obtained and read in full (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A PRISMA flow chart showing steps followed in retrieving and screening articles for review.

Figure 1: A PRISMA flow chart showing steps followed in retrieving and screening articles for review.

The systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta - data Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

All the studies included in this review presented self-reported data on alcohol use. A total of 56% of the studies used probability sampling strategy and 13% used non probability sampling. The rest did not report on sampling strategy utilised. 82% of studies had an adequate sample size of at least 300 participants. 69% of studies employed a validated tool to ascertain alcohol use. All the studies (100%) used a questionnaire/single question and provided details of tool used. 60.8% of the studies had adequate participation rate of at least 60%. All studies included in this review described study participants. Quality Appraisal results of all the 23 studies are provided in Table 1.

|

Representativeness of the Sample |

Ascertainment of Alcohol Use |

||||||

|

Reference |

Probability Sampling |

Non Probability Sampling |

Adequate Sample size 300 or more participants |

Validated tool used |

Questionnaire including a single question |

Adequate response/participation rate 60% or more |

Study subjects described |

|

Adeyiga, et al |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

Anteab K, et al. |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

Barthelemy, et al. |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

Chukwuonye, et al. |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Croxford J. and Viljoen D |

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

Desmond, et al. |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

English, et al. |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Jones, et al. |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

Kabwama, et al. |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Louw, et al. |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

Martinez, et al. |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

Mitsunaga T and Larsen U |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Morojere, et al. |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

Morojere, et al. |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Namagembe. et al. |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Ordinioha B and Brisibe S |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

Peltzer K, et al. |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Phaswana, et al. |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

Simbayi, et al. |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

Siegfried, et al. |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

Tumwesigye, et al and Kasirye, et al. |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

Vythilingum, et al. |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Williams, et al. |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

Table 1: Checklist for Quality of Studies included in the Review Source: Adapted from Wong et al. The absence of X can mean either No or not reported.

Data Extraction

A pre - defined framework was developed to aid extraction of data from selected studies. The following data was extracted:

Study participants and setting

- Study Title

- Lead Author

- Publication Years

- Location of study(Country of origin)

- Duration and period of data collection

- Number of study participants

- Characteristics of study participants

Study Protocol

- Study design

- Study inclusion criteria

- Instrument used for alcohol use

- Data collection methods

- Age of respondents when alcohol was measured

- Status either pregnant or not pregnant when alcohol use was measured

Study outcomes

- Prevalence of alcohol use

- Negative consequences associated with alcohol use

Assessment of Methodological Quality

There was no ethical clearance required by this study as all papers were published in scientific peer reviewed journals.

Results

Characteristics of studies selected

Most of the studies (n=13) were health facility based while 10 studies were community based. Health facility based studies were conducted among women seeking antenatal care, delivery, and PMTCT, Tuberculosis and STI services. Only a few studies (n=8) investigated negative consequences related to excessive alcohol use among women of child bearing age.

All the studies identified were conducted in East, West, Central and Southern Africa. Majority of the studies were conducted in South Africa(n=10),followed by Uganda(n=4),Nigeria(n=2), Congo (n=2), Tanzania (n=1) and Ghana (n=1), Lesotho (n=1) and Ethiopia (n=1). The WHO World Health survey which is also included was conducted in 20 African countries including Burkina Faso, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Coted’voire, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Mauritius, Morocco, Namibia, Senegal, South Africa, Swaziland, Tunisia, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Timeframes measured were not similar as some reported current use, use within the last thirty days or twelve months preceding survey. All the studies varied in study population and measure and definition of alcohol use. The terms used to define excessive alcohol use differed in the various studies. They included; harmful alcohol use, hazardous drinking, alcohol dependence, binge drinking, frequent alcohol use, heavy drinking and risky drinking. Studies also used various tools to measure excessive alcohol use and these were Cut down, Annoyed, Guilt, Eye opener (CAGE) questionnaire, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)questionnaire and Tolerance Annoyed Cut-down Eye opener(TACE). The findings have been categorized into two study populations: Those recruited from the general population and those recruited from health facilities.

Prevalence of excessive alcohol use among women of childbearing age in Africa among identified studies

Some studies included in this review assessed more than one form of excessive alcohol use. Five studies reported on frequent alcohol consumption and this ranged from 3.9% in Tanzania to 34.9% in Ghana [23-27] . Heavy alcohol use was reported by five studies and ranged from 0.9% in Mauritius to 25.4% in Congo [22,27-30]. Binge drinking was assessed by eleven studies and ranged from less than one percent in Mpumalanga South Africa to 35% in Cape Town South Africa [24,26,29,31-37].

Risky alcohol use was documented by four studies and ranged from 0.3% in Mauritius to 57.5% in Chad [22,35,38,39] .Four studies assessed problem drinking and this varied from 2.16% to 25%in Cape town South Africa [38,40-42] .Harmful alcohol use, hazardous drinking and alcohol dependence was mostly reported in South Africa and Lesotho and ranged from to 1.1 to 13% [33,39,41,43].

Eight studies investigated negative consequences of excessive alcohol use among women in the reproductive age group. These include; multiple sexual partnerships and HIV exposure, alcohol exposed pregnancies, FAEE in neonates,injury, poor physical health, high risk sex, alcohol related disorders such as failing to do what was expected of them after drinking and being unable to stop drinking once they started drinking [25,27,30,34,35,38,40,42]. Details of the 23 studies that met the selection criteria are summarized in Tables 2-4.

|

Reference |

Country |

Alcohol Use definition |

Study Population |

Women |

Prevalence of Alcohol Use |

|

Adeyiga, et al. |

Ghana |

Frequent Use |

Gynaecologic outpatient facility in Accra |

394 |

12.9% drank daily 36.3% drank 5 or more units per week |

|

Barthelemy, et al. |

Congo |

Consuming more than 1 litter of alcohol a day defined as heavy drinking |

ANC attendees |

240 |

25.4% reported heavy drinking |

|

Croxford J, and Viljoen D, et al. |

Western Cape South Africa |

Moderate 5-10 units absolute alcohol/week or binges of 5-10 units/occasion) or heavy(>10unitsAA/week or binges of >10 units AA/week or binges of > 10 units per occasion) |

ANC Attendees |

636 |

23.7% of all women reported moderate or heavy alcohol use in binge pattern |

|

Desmond, et al. |

Kwazulu, Natal(South Africa) |

Binge drinking as consuming 3 or more drinks on a single occasion |

PMTCT program attendees |

1201 |

35% of drinkers (221/1201) binged twice a month |

|

English, et al. |

Uganda |

Current use Heavy alcohol consumption(not defined) |

Pregnant women reporting to maternity ward |

505 |

6.3% reportedly drank heavily 3.2% drank moderately |

|

Louw J, et al. |

Mpumalanga, South Africa |

Binge drinking as drinking 4 or more drinks per single occasion AUDIT cut off score of 5 or more as hazardous/harmful drinking |

ANC attendees |

1497 |

1.1% of all sampled women reported hazardous/ harmful drinking 0.98% of all sampled women reportedly drank 4 or more drinks on occasion daily or weekly |

|

Namagembe, et al. |

Uganda |

Taking 4 or more drinks on single occasion as binge drinking

Risky drinking defined as averaging more than one drink per day |

ANC attendees |

610 |

2.6% binged 6 or more drinks on single occasion 9% drank 4 or more drinks per single occasion 7.9% reported risky drinking |

|

Ordinioha B, et al. and Brisibe S, et al. |

Nigeria |

Taking 4 or more standard units of drink at a single occasion as binge drinking Frequent drinking defined as consuming 14 units of alcohol in a week |

ANC women |

221 |

25.79% of all sampled women binged 2.2% of all sampled women drank frequently |

|

Peltzer K, et al. |

South Africa |

AUDIT Score 8 and above Defined as hazardous or harmful drinking AUDIT score of 20 or more as alcohol dependence AUDIT score 8-19 defined as high risk drinking |

TB Patients aged 18 years and above |

2,229 |

13.0% reported hazardous/harmful drinking 3.4% reported alcohol dependence 9.5% reported high risk drinking |

|

Phaswana, et al. |

South Africa (GertSibande district) |

Consuming 4 or more drinks on a single occasion defined as binge drinking |

ANC attendees |

984 |

7.4% reported consuming 4 or more drinks on an occasion less than monthly 2.0% reported having 4 or more drinks on an occasion monthly 1.8% reported taking 4 or more drinks on an occasion weekly |

|

Simbayi, et al, 2007 |

Capetown South Africa |

Problem drinking defined as being unable to stop drinking (AUDIT score> or =9).

Monthly consumption of 4 drinks for women on any single occasion defined as binging |

STI Clinic attendees |

92 |

25% of women reported problem drinking 9% of women reported Binge drinking |

|

Vythilingum, et al. |

Capetown South Africa |

AUDIT score of 20 and above defined as problem drinking |

ANC Attendees |

323 |

25% of women reported problem drinking 9% of women reported Binge drinking |

|

Williams, et al. |

DRC Congo Brazaville |

Consuming 4 or more drinks on single occasion defined as binge drinking |

ANC attendees |

3099 |

2.16%of all sampled women reported alcohol dependence/problem drinking 20.2% reported binge drinking during pregnancy |

Table 2: ShowingPrevalence of Excessive Alcohol Use and its Negative Consequencesamong Women in Reproductive Age group in Africa as Reported by Selected Studies (Health Facility Based Studies)

|

Reference |

Country |

Alcohol use definition |

Study Population |

Women |

Prevalence of Alcohol Use |

|

Anteab K, et al, |

Bahir Dar City Northwest Ethiopia |

Binging described as 4 or more drinks on single occasion |

Pregnant Women |

810 |

7.5% binged

|

|

Chukwuonye, et al, |

Nigeria Abia State |

Frequent drinking as drinking 5 or more days a week |

General population |

1428 |

0.9% |

|

Jones, et al. |

Capetown South Africa |

Problem drinking |

Pregnant and non-pregnant women |

382 |

13.6% |

|

Kabwama, et al. |

Uganda |

High end alcohol users defined as women consuming 4 or more drinks on an occasion in last 30 days |

Women |

1814 |

3.9% drunk daily 4.6%of women without partners drank daily. 7.0% Alcohol Abuse

|

|

Morojere, et al. |

South Africa |

-3 or more drinks on single occasion is risky drinking -Problem drinkers defined as those who “drunk too much” |

Men and women |

95 |

12.2% of all women problem drinkers 29.4% of all women were risky drinkers |

|

Morojere, et al. |

South Africa |

Strict sense of AEP defined as Consuming 5 or more drinks per occasion |

Urban and rural Women |

1018 |

2.4% Urban 8.5% Rural |

|

Siegfried, et al. |

Lesotho |

Hazardous drinking as Consuming more than 225g of ethanol per week for women and those engaged in bouts of heavy drinking for 1-2 days a month or more in last 12 months |

General population |

279 |

9% of women hazardous drinkers |

|

Tumwesigye et al. & Kasirye, et al. |

Uganda |

Frequent Heavy drinker takes 5 or more drinks on an occasion and drank at least once in a month in last 12 months |

General population |

754 |

6.5% frequent heavy drinkers 17.6% of women near daily drinkers |

Table 3: ShowingPrevalence of Excessive Alcohol Use and Negative Consequences among Women in Reproductive Age group in Africa as Reported by selected Studies (Population/Community Based Studies)

|

Reference |

Country |

Heavy drinkers |

Risky Single occasion drinkers |

Sample size |

|

Martinez P, et al. |

Burkina Faso |

33.5 |

31.0 |

2543 |

|

|

Chad |

41.3 |

57.5 |

2435 |

|

|

Congo |

5.2 |

15.3 |

1185 |

|

|

Cote d’Ivore |

7.1 |

6.9 |

1339 |

|

|

Ethiopia |

5.3 |

1.8 |

2535 |

|

|

Ghana |

4.4 |

3.3 |

2159 |

|

|

Kenya |

14.0 |

12.4 |

2537 |

|

|

Malawi |

11.5 |

36.4 |

3082 |

|

|

Mali |

8.6 |

22.4 |

1749 |

|

|

Mauritius |

0.9 |

0.3 |

2016 |

|

|

Namibia |

12.1 |

17.8 |

2379 |

|

|

Senegal |

13.0 |

21.4 |

1223 |

|

|

South Africa |

15.6 |

30.5 |

1228 |

|

|

Swaziland |

8.8 |

18.5 |

1189 |

|

|

Zambia |

17.7 |

27.6 |

2088 |

|

|

Zimbabwe |

7.2 |

18.3 |

2553 |

Table 4: Showing Prevalence of Heavy and Risky Alcohol Use among women in 20 African Countries: Data from World Health Survey 2011

As part of the world health survey, data was collected in 20 African countries on alcohol use among women [22]. in total 40,739 women aged 18 years and above were interviewed between 2002-2004.Heavy drinkers were defined as those who had consumed a total of 15 or more standard drinks during the last 7 days and risky single occasion drinkers were defined as those who consumed at least 5 or more standard drinks of alcohol on at least one day of the previously week. Heavy drinking varied from 4% in Ghana to 41% in Chad. Risky single occasion alcohol use ranged from less than one percent in Mauritius to 58% in Chad. Rates of risky single-occasion drinkers among current drinkers were below 20% in 9 countries.

Discussion

Only eight studies in this review of papers on various forms of excessive alcohol use among women of child bearing age in Africa, we note that not much has been documented about prevalence estimates of excessive alcohol use among women and related burdens in Africa. Save for the WHO World Health survey which was carried out in 20 out of 54 countries in Africa that investigated heavy and risky single occasion drinking, most of what is known about excessive alcohol use among women in Africa is documented in only 8 countries that is Congo, Ghana, Ethiopia, Lesotho, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania and Uganda. Related studies on the continent have mainly documented alcohol use (any amount) and alcohol abstinence.More research should be implemented in other countries to adequately estimate the prevalence and burden of excessive alcohol use among women on the continent.

This study reveals thatheavy drinking among women ranged from 0.9% in Mauritius to 25.4% in Congo and binge drinking ranged from less than one percent in Mpumalanga South Africa to 35% in Cape Town South Africa. These results fall in similar range as those of other womenoutside Africa. About a third of women (35%) engaged in binge drinking in Copenhagen during early pregnancy [44] .In the US, binge drinking during pregnancy was reported by 3.9% and has been recorded at 2.7% in Europe [45,46].

Binge drinking was the most common form of excessive alcohol use documented by most studies in this review. This maybe because it is the most prevalent form of excessive alcohol use. Given their socially ascribed roles as caretakers, women are engaged in brewing and serving alcohol on functions such as wedding and funerals which presents an opportunity for them to indulge in risky single occasion drinking. It should be noted that binge drinking is the pattern of alcohol use associated with increased physical and emotional harm, including violence, accidents, unplanned pregnancy, unprotected sex, STD, HIV and FASD [10,46]. It has also been linked to stress, anxiety, traumatic events and depression [47] .These finding are catastrophic given women’s roles in society. FASD in particular may result into birth defects and other lifelong conditions such mental illness and illegal behaviour [48] .This may further constrain Africa’s poorly resourced healthcare systems. Efforts are thus required by governments to address cultural perceptions and norms that predispose women to binge drinking.

The highest prevalence of excessive alcohol use were reported in Chad, South Africa and Nigeria and the lowest in Mauritius. For some women increased opportunities for them to perform traditionally male roles may have presented more opportunities for women to increase their drinking, with more adverse consequences [49] .In some societies alcohol consumption is frowned upon. It may be for the same reason that excessive alcohol use was not reported in any of the Moslem countries. This relates to findings of other studies that have espoused the roles of religious values and belief systems in alcohol consumption [50].

Only eight studies in this review representing three countries of Uganda, Tanzania and South Africa assessed negative consequences related to drinking among women. These include FAEE, HIV acquisition, alcohol exposed pregnancies, intimate partner violence, mortality, poor physical health, alcohol use disorders, risky sexual behaviours. Similarly, other authors have found that women’s intoxication reduces social control of their sexuality, making them either more sexually uninhibited or more sexually vulnerable [51]. Findings of this study indicate that alcohol related consequences are considerable among women. Since patterns of drinking have been linked between alcohol and health [52,53]. More in-depth studies and analyses are needed to look at the patterns and nature of drinking among women in Africa in relation to alcohol related problems.

Strengths of this study include a thorough search strategy for literature and well defined inclusion and exclusion criteria that was followed strictly. Findings of this study should also be interpreted carefully as each of the studies included has its own limitations. It was not possible to conduct meta-analysis on various forms of alcohol use among women of childbearing age for different countries as only a few countries had two or more studies that had reported particular forms of alcohol use. Even those that had two or more studies reporting on specific forms of excessive alcohol use (binge drinking, heavy drinking, frequent drinking, risky drinking and hazardous drinking) had not all reported on confidence intervals and or standard errors so meta-analyses were not possible. Most information was self-reported and may suffer recall bias and excessive alcohol use may have been underreported due to social desirability. None the less, this study provides insight into the magnitude of the challenge of excessive alcohol use among women of childbearing age on the continent.

Conclusion

Recent research on prevalence of excessive alcohol use among women in Africa in particular is dismal. The differences in prevalence figures reflect differences in drinking culture and social attitudes toward drinking. It may also reflect differences in settings of respondents, their characteristics as well as differences in study protocols. Concerted efforts are therefore required by Health systems in this part of the world to promote behaviour change communication to shape the attitudes, knowledge and behaviour of these women.

Alcohol misuse is likely to pose a burden on resources of many African governments if measures are not instituted in place to reduce alcohol harm. Alcohol harm reduction strategies should be put in place.

Funding

Not applicable

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Thecla Arinaitwe, a librarian whose skills were instrumental in searching for these articles.

References

- Benjamin Rollanda, Ingrid de Chazeron, Françoise Carpentier,Fares Moustafa, AlainViallong; et al. (2017) Comparison between the WHO and NIAAA criteria for binge drinking on drinking features and alcohol-related aftermaths: Results from a cross-sectional study among eight emergency wards in France. Drug and alcohol dependence 175: 92-98.

- Rollanda B, de Chazeron I, Carpentier F, Moustafa F, Viallong A, et al. (2017) Comparison between the WHO and NIAAA criteria for binge drinking on drinking features and alcohol-related aftermaths: Results from a cross-sectional study among eight emergency wards in France. Drug and alcohol dependence 175: 92-98.

- Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG (2001) The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in. Primary care.

- Henry W, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Castillo S, et al. (1994) Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college: A national survey of students at 140 campuses. Jama 272: 1672-1677.

- National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the Substance Abuse and mental Health Services Administration defines heavy alcohol use as binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past month 2015.

- Reid MC, Fiellin D, O'Connor P(1999) Hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in primary care. Archives of internal medicine 159: 1681-1689.

- O'FlynnN (2011) Harmful drinking and alcohol dependence: advice from recent NICE guidelines. British Journal of General Practice 61: 754-756.

- Tramacere I, Pelucchi C, Bonifazi M, Bagnardi V, Rota M, et al. (2012) A meta-analysis on alcohol drinking and the risk of Hodgkin lymphoma. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 21: 268-273.

- Jürgen R, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, et al. (2009) Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The lancet 373: 2223-2233.

- Nolen-Hoeksema S (2004) Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical Psychology Review 24: 981-1010.

- Richard W, Vogeltanz N, Wilsnack S, Harris R (2000) Gender differences in alcohol consumption and adverse drinking consequences: cross-cultural patterns.Addiction 95: 251-265.

- Pitpitan EV, Kalichman SC, Eaton LA, Sikkema KJ, Watt MH, et al. (2012) Gender-based violence and HIV sexual risk behavior: alcohol use and mental health problems as mediators among women in drinking venues, Cape Town. Social science & medicine 75: 1417-1425.

- Krulewitch C (2006) Alcohol consumption during pregnancy23: 101-34

- Latino-Martel P, Chan DSM, Druesne-Pecollo N, Barrandon E, Hercberg S, et al. (2010) Maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy and risk of childhood leukemia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers 19: 1238-1260.

- Lorente C, Sylvaine C, Janine G, Ségolène A, Fabrizio B, et al. (2000) Tobacco and alcohol use during pregnancy and risk of oral clefts. Occupational Exposure and Congenital Malformation Working Group. American Journal of Public Health 90: 415.

- Heertum KV, Rossi B (2017) Alcohol and fertility: how much is too much?. Fertility Research and Practice 3: 10.

- Bingham RJ (2015) Latest evidence on alcohol and pregnancy. Nursing for women’s health 19: 338-344.

- May PA, de Vries MM, Marais A-S, Kalberg WO, Adnams CM, et al. (2016) The continuum of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in four rural communities in South Africa: Prevalence and characteristics. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 159: 207-218.

- Sher L (2008) Research on the neurobiology of alcohol use disorders. Nova Publishers.

- Dumbili EW (2016) She encourages people to drink: A qualitative study of the use of females to promote beer in Nigerian institutions of learning. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 23: 337-343.

- Ferreira-Borges C, Parry CDH, Babor TF (2017) Harmful use of alcohol: A shadow over sub-Saharan Africa in need of workable solutions. International journal of environmental research and public health 14: 346.

- Martinez P, Røislien J, Naidoo N, Clausen T (2011) Alcohol abstinence and drinking among African women: data from the World Health Surveys. BMC Public Health 11: 160.

- Adeyiga G, Udofia EA, Yawson AE (2014) Factors associated with alcohol consumption: A survey of women childbearing at a national referral hospital in Accra, Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health 18: 152-165.

- Chukwuonye I I, Chuku A, Onyeonoro UU, Madukwe OO, Oviasu E, et al. (2013) A rural and urban cross-sectional study on alcohol consumption among adult Nigerians in Abia state. International Journal of Medicine and Biomedical Research 2: 179-185.

- MitsunagaT, Larsen U (2008) Prevalence of and risk factors associated with alcohol abuse in Moshi, northern Tanzania. Journal of biosocial science 40: 379-399.

- Ordinioha B, Brisibe S (2015) Alcohol consumption among pregnant women attending the ante. natal clinic of a tertiary hospital in South. South Nigeria. Nigerian journal of clinical practice 18: 13-17.

- Mbona TN, Rogers K (2005) Gender and the major consequences of alcohol consumption in Uganda. Alcohol, gender and drinking problems 189.

- Barthélémy T, Andy M, Roger M (2011) Effect of maternal alcohol consumption on gestational diabetes detection and mother-infant’s outcomes in Kinshasa, DR Congo. Open J Obstet Gynecol 1: 208-12.

- Croxford J, Viljoen D (1999) Alcohol consumption by pregnant women in the Western Cape." South African Medical Journal 89: 962-965.

- English L, Mugyenyi GR, Ngonzi J, Kiwanuka G, Nightingale I, et al (2015) Prevalence of Ethanol Use Among Pregnant Women in Southwestern Uganda. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada 37: 901-902.

- Anteab K, Balem D, Mulualem M (2014) Assessment of Prevalence and Associated Factors of Alcohol Use during Pregnancy among the dwellers of Bahir-Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia.

- Desmond K, Milburn N, Richter L, Tomlinson M, Greco E, et al (2012) Alcohol consumption among HIV-positive pregnant women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: prevalence and correlates. Drug and alcohol dependence 120:113-118.

- Louw J, Peltzer K, Matseke G (2011) Prevalence of alcohol use and associated factors in pregnant antenatal care attendees in Mpumalanga, South Africa. Journal of Psychology in Africa 21: 565-572.

- Kabwama SN, Ndyanabangi S, Mutungi G, Wesonga R, Bahendeka SK, et al (2016) Alcohol use among adults in Uganda: findings from the countrywide non-communicable diseases risk factor cross-sectional survey. Global Health Action 9: 31302.

- Namagembe I, Jackson LW, Zullo MD, Frank SH, Byamugisha JK, et al (2010) Consumption of alcoholic beverages among pregnant urban Ugandan women. Maternal and Child Health Journal 14: 492-500.

- Phaswana-Mafuya NR, Peltzer K, Davids A (2009) Intimate partner violence and HIV risk among women in primary health care delivery services in a South African setting. Journal of Psychology in Africa 19: 379-386.

- Williams AD, Nkombo Y, Nkodia G, Leonardson G, Burd L et al (2013) Prenatal alcohol exposure in the Republic of the Congo: prevalence and screening strategies. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology 97: 489-496.

- Morojele N, Kachieng’a MA, Nkoko M, Moshia KM, Mokoko E, et al (2004) Perceived effects of alcohol use on sexual encounters among adults in South Africa. African Journal of Drug and Alcohol Studies 3: 1-20.

- Peltzer K, Louw J, Mchunu G, Naidoo P, Matseke G, et al (2012) Hazardous and harmful alcohol use and associated factors in tuberculosis public primary care patients in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9: 3245-3257.

- Jones HE, Browne FA, Myers JB, Carney T, Ellerson RM, et al (2011) Pregnant and nonpregnant women in Cape Town, South Africa: drug use, sexual behavior, and the need for comprehensive services. International Journal of Pediatrics.

- Vythilingum B, Roos A, Faure SC, Geerts L, Stein DJ (2012) Risk factors for substance use in pregnant women in South Africa. SAMJ: South African Medical Journal 102: 853-854.

- Simbayi LC , Kalichman SC, Cain D, Cherry C, Jooste S, et al (2007) Alcohol and risks for HIV/AIDS among sexually transmitted infection clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. Substance Abuse 27: 37-43.

- Siegfried N, Parry CDH, Morojele NK, Wason D et al (201) Profile of drinking behaviour and comparison of self-report with the CAGE questionnaire and carbohydrate-deficient transferrin in a rural Lesotho community. Alcohol and Alcoholism 36: 243-248.

- Iversen ML, Sørensen ON, Broberg L, Damm P, Hedegaard M, et al (2015) Alcohol consumption and binge drinking in early pregnancy. A cross-sectional study with data from the Copenhagen Pregnancy Cohort. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 15: 327.

- Denny CH, Acero CS, Naimi TS, Kim SY (2019) Consumption of alcohol beverages and binge drinking among pregnant women aged 18–44 years-United States, 2015-2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 68: 365.

- Popova s, Lange S, Probst C, Gmel G, Rehm J, et al (2018) Global prevalence of alcohol use and binge drinking during pregnancy, and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Biochemistry and Cell Biology 96: 237-240.

- Kuntsche E, Kuntsche S, Thrul J, Gmel G (2017) Binge drinking: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychology & Health 32: 976-1017.

- Popova S , Lange S, Probst C, Gmel G, Rehm J, et al (2017) Estimation of national, regional, and global prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy and fetal alcohol syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health 5: 290-299.

- Bergmark KH (2004) Gender roles, family, and drinking: Women at the crossroad of drinking cultures. Journal of Family History 29: 293-307.

- Kalema D, Vanderplasschen W, Vindevogel S, Derluyn I (2016) The role of religion in alcohol consumption and demand reduction in Muslim majority countries (MMC). Addiction 111: 1716-1718.

- Testa M, Livingston JA (2018) Women’s alcohol use and risk of sexual victimization: Implications for prevention. Sexual Assault Risk Reduction and Resistance 135-172.

- WHO (2019) Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Rehm J, Hasan OS, Imtiaz S, Probst C, Roerecke M, et al. (2018) Alcohol and noncommunicable disease risk. Current Addiction Reports 5: 72-85.

Citation: Agiresaasi A, Nassanga G, Tumwesigye N (2021) Excessive Alcohol Use and Its Negative Consequences Among Women of Child Bearing Age in Africa: A Systematic Review. J Alcohol Drug Depend Subst Abus 8: 025.

Copyright: © 2021 Apophia Agiresaasi, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.