Factors Contributing to Unsuccessful Central Line Placement in the Neck and Chest

*Corresponding Author(s):

Manuel E PortalatinDepartment Of Surgery, St. Joseph’s University Medical Center, New Jersey, United States

Tel:+1 9048740461,

Email:portom1986@gmail.com

Abstract

Objective

To date, no prospective studies have analyzed which multivariate factors correlate to a successful placement. We question whether MAP and obesity are contributors to central line placements in the IJ and subclavian veins.

Methods

All trauma patients aged 14 to 90 requiring central venous access were considered. Data on obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypotension, ventilator dependency, contractures, inline cervical spine immobilization, placement site, and emergency cases was collected. Pediatrics cases and those in which the form was incorrect or incomplete were excluded. Of the 145 cases, 134 were included in the analysis. Logistic regression was used to analyze the raw data, using IBM SPSS 2014 software.

Results

The study population was 134 patients. BMI and MAP did not contribute to line failure (p<0.297, p<0.915), but MAP >60 was correlated with increase success in line placement (p<0.002). Medical residents and surgical residents were more likely to have failures over emergency medicine residents.

Conclusion

There are inherent risks which need to be outlined to the patient. Lack of preparation and experience increases the likelihood of devastating complications. Central venous catheter placement can be done safely and provide much needed access for critically ill patients, with time, guidance, and volume.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Central line placement is a commonly practiced procedure done in an inpatient setting. Multiple large prospective multi-center studies have examined the use of ultrasound and whether its use affects successful placement; this has since become the standard of care [1]. However, to date, no prospective studies have analyzed which factors correlate to a successful placement. We propose that MAP and obesity are contributors to whether central line placements in the IJ and subclavian veins are successful.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a prospective observational study at a Level II trauma regional medical center. Variables such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypotension, ventilator dependency, contractures, need for inline cervical spine immobilization (i.e., cervical collar), location of placement, and need for emergent placement (i.e., during a cardiac arrest or code) were documented. In addition, resident’s specialty (surgical, EM, and IM) and level of experience (PGY I-VI) were considered. Inclusion criteria of patients between the ages 14 to 90 who required central venous access was selected. This criterion was met by 134 participants. There were 11 patients excluded, due to being pediatrics cases, or those in which the form was not filled out to completion.

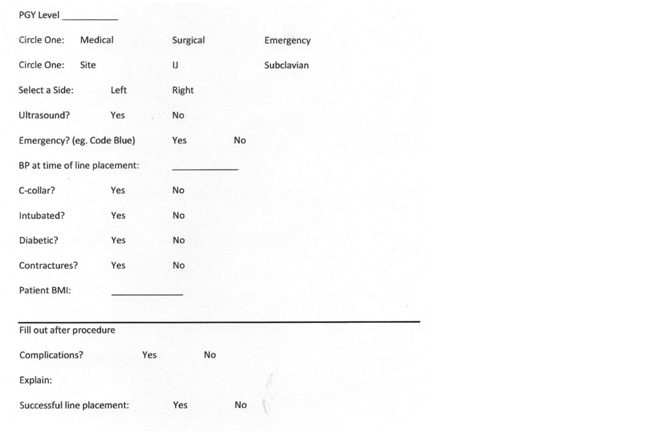

Written procedural consent was obtained prior to the central line placement. Table 1 lists the demographics of this cohort. Residents performing the procedure were required fill out a two-part form as seen in figure 1. Table 2 lists the parameters used as part of the overall analysis, separated into successful and unsuccessful placements. Central lines were placed either in the Internal Jugular vein (IJ) or the subclavian vein and were completed under sterile conditions according to the current standard of care [2-4]. In this study, central line success is defined as cannulation and placement of the central line on the first attempt without the need for needle reposition. Chest X-rays were obtained on all lines placed. Hypotension was defined at MAP 30. Logistic regression was used to analyze the raw data, using IBM SPSS 2014 software. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All information was collected from the institution’s patient registry. The institutional review board at this institution approved both the protocol and data collection.

|

Variable |

Total cohort (n = 134) |

|

Male |

78 |

|

Female |

56 |

|

Average Age and Range |

57 (18-92) |

|

Average BMI and Range |

30.1 (15.9-53.4) |

|

BMI>25 |

100 |

|

BMI 30-35 |

35 |

|

BMI 35-40 |

18 |

|

BMI>40 |

13 |

|

C-collar |

23 |

|

Average MAP and Range |

79.8 (30.6-147) |

|

MAP<60 |

24 |

|

MAP>60 |

110 |

Table 1: Demographics.

Figure 1: Residents performing the procedure were required fill out a two-part.

Figure 1: Residents performing the procedure were required fill out a two-part.

|

Variable |

Total (n = 134) |

Successful (n = 96) |

Unsuccessful (n = 38) |

|

Male |

78 |

56 |

22 |

|

Female |

56 |

40 |

16 |

|

DM |

37 |

23 |

14 |

|

US |

86 |

66 |

20 |

|

Emergent |

20 |

12 |

8 |

|

C-collar |

23 |

13 |

10 |

|

Intubated |

74 |

53 |

21 |

|

Contracture |

9 |

5 |

4 |

|

Site |

|||

|

IJ |

87 |

67 |

20 |

|

S |

47 |

29 |

18 |

|

Specialty |

|||

|

Medical |

26 |

15 |

11 |

|

Surgical |

80 |

57 |

23 |

|

Emergency |

28 |

24 |

4 |

|

PGY Year |

|||

|

1 |

30 |

18 |

12 |

|

2 |

50 |

37 |

13 |

|

3 |

36 |

30 |

6 |

|

4 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

|

5 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

6 |

10 |

6 |

4 |

Table 2: Analysis parameters, success versus failure.

RESULTS

Table 3 shows that successful line placement demonstrated statistical significance for the following: Increased Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) (p-value 0.002), site placement of the internal jugular vein (p-value 0.015), emergent line placement (p-value 0.0001), use of ultrasound (p-value 0.021), and the presence of a c-collar (p-value 0.007).

|

Variable |

p Value Successes |

p Value Failures |

|

Male |

- |

- |

|

Female |

- |

- |

|

DM |

0.621 |

0.87 |

|

US |

0.021 |

0.206 |

|

Emergent |

0 |

0.327 |

|

C-collar |

0.007 |

0.061 |

|

Intubated |

0.536 |

0.429 |

|

Contracture |

0.945 |

0.297 |

|

Site |

||

|

IJ |

0.015 |

0.226 |

|

S |

- |

- |

|

Specialty |

||

|

Medical |

0.586 |

0.039 |

|

Surgical |

0.786 |

0.02 |

|

Emergency |

0.576 |

0.104 |

|

PGY Year |

||

|

1 |

0.801 |

0.827 |

|

2 |

0.996 |

0.049 |

|

3 |

0.446 |

0.17 |

|

4 |

0.482 |

0.438 |

|

5 |

0.783 |

0.551 |

|

6 |

0.956 |

0.445 |

Table 3: Regression analysis of parameters and contribution to success and failure.

BMI and MAP were not significant in line failure (p-value 0.297 and 0.915, respectively). Statistically significant factors include IM and surgical specialties (p-value 0.039 and 0.020, respectively), and PGY-2 year (p-value 0.049).

DISCUSSION

In this study, analysis was conducted for factors that affect the successful and unsuccessful central line placement. BMI has previously been cited as a factor for central line placement [3-7]. The US Department of Health and Human Services defines obesity as a BMI greater than 30 [3]. In this cohort, the average BMI was 30.21, with the use of a value of 30 as a benchmark. BMI in this study was not significant for successful line placement or a contributor to line failure. An increased MAP, however, was found to be significant for success in line placement. A MAP of 60 was used because a range of 60-65 indicates hypoperfusion and is a recommended time to begin pressor medication [4-6]. With increase in volume, it may be easier to place these central lines. These central lines are non-emergent and often done under controlled setting often under the supervision of a senior resident. Most of the failed attempts did occur with MAP >60 and by PGY-2 residents, approximately 42%. It is likely that these perceived “easier lines” are given to more inexperienced residents for learning purposes and without supervision, may be more likely to fail.

In this study all lines placed in the IJ site were accompanied by ultrasound. Since the IJ placed central lines were more predictive of success, ultrasound guidance was also found to be significant for successful line placement. Reasons have been elaborated upon by other studies but are important to note here as well [7-9]. Proper visualization of access site is critical in safe line placement with a reduction in complications such as pneumothorax and hematoma [8-10]. There is also a significant decrease in the attempts of access [7-11].

Unsuccessful lines were significant for medical vs. non-medical specialties and PGY-2 year. Of note, surgery and medicine were more likely to have failed lines at 29% and 42%, respectively in comparison to emergency medicine, with failed lines at 14%. Table 4 illustrates the failed central line placement by specialty. Any additional line failures after PGY-4 year only apply to Surgery and accounts for a 6% increase in failure rate relative to IM and ED. A reason that PGY-2 line failure rate increased relative to other classes is that PGY-2 residents placed the majority of lines, 50 vs. 36 and 30 for the PGY-1 and PGY-3 class, respectively. They were also the class likely to be manning the ICU at this institution. Although no data was collected for at what time or under what conditions/reasons the lines were placed, it is likely that the lines were unsupervised.

|

Emergency (n = 6) |

Surgical (n = 30) |

Medical (n = 22) |

|

|

Total Unsuccessful |

4 |

23 |

11 |

|

Total Unsuccessful Internal Jugular |

2 |

7 |

11 |

|

Percentage Unsuccessful Internal Jugular |

50% |

30.40% |

100% |

|

Total Unsuccessful Subclavian |

2 |

16 |

- |

|

Percentage Unsuccessful Internal Jugular |

50% |

69.60% |

- |

Table 4: Line placement by percentage.

A majority of failed central lines for surgical residents were for those attempted via subclavian access, at approximately 30%, was also seen for emergency residents, at 50%. No attempts were made for subclavian access by medical residents. The total line placement for subclavian access by surgical residents is 28 attempts, whereas for Emergency Residents it is 10 attempts. In our cohort, more inexperienced residents are the first to attempt a subclavian line which may reflect the relative increase in failure rate. There is data to suggest that if all steps are done properly, then the actual line placement rate should not change [12-16]. Not accounted for in our study were factors such as those with more protracted courses, ICU vs. floor managed, and coagulopathy or sepsis. There is limited data, however, on how length of stay or severity of illness can impact line placement. Future studies may then focus on whether this can change line placement outcome.

There are several limitations to our study. BMI was obtained using bed weighing in the trauma bay or in the wards. The accuracy of the weight may vary depending on factors such as extra equipment. It is similarly difficult to measure height accurately at bedside in both emergent and inpatient cases and is often estimated. Another limitation includes the larger numbers of surgical lines vs. other specialties. A more exact analysis could likely be drawn if the numbers of each specialty that placed lines were better represented. Further investigation should be carried out for femoral line placement as compared to subclavian and IJ lines.

CONCLUSION

Although most TLC lines are placed with relative ease and minimal complications, the ultimate conclusion drawn should be that like any procedure there are inherent risks which need to be outlined to the patient. Our study demonstrated that MAP >60 was shown to be indicative of successful line placement and that inexperienced practitioners will have more failed line placements. Complications from central venous catheters have the potential to be devastating when there is lack of preparation and experience. With time, guidance from experienced personnel, and a larger number of cases in which to learn the technique, central venous catheter placement can be done safely and provide much needed access for critically ill patients. Resident surveys could be conducted to decipher comfort level, understanding of the anatomy, and amount of hands-on experience before attempting line placement initially.

DECLARATIONS

The authors would like to thank the Emergency Department and SICU staff at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center for their support and invaluable work. Data was collected and made freely available to authors involved and to the statistician, and can be made freely to future researchers. No funding was given for this project. Consent was obtained from patients prior to the procedure and understood the aim for publication. There are no competing interests among the authors. Author contributions were as follows:

Study conception and design: Zuberi, Rebein, Fakhoury, Portalatin, Madlinger

Acquisition of data: Fakhoury, Portalatin, Broncato

Analysis and interpretation of data: Zuberi, Portalatin

Drafting of manuscript: Fakhoury, Portalatin, Zuberi, Willis

Critical Revision: Zuberi, Fakhoury, Portalatin, Willis, Shahzad

REFERENCES

- Leung J, Duffy, M, Finkh A (2006) Real-Time ultrasonographically-guided internal jugular vein catheterization in the emergency department increases success rates and reduces complications: A randomized, prospective study. Ann Emerg Med 48: 540-547.

- Rupp SM, Apfelbaum JM, Blitt C, Caplan RA, Connis RT, et al. (2012) Practice guidelines for central venous access: A report by the american society of anesthesiologists task force on central venous access. Anesthesiology 116: 539-573.

- Orpana HM, Berthelot JM, Kaplan MS, Feeny DH, McFarland B, et al. (2010) BMI and mortality: Results from a national longitudinal study of Canadian adults. Obesity 18: 214-218.

- Avni T, Lador A, Lev S, Leibovici L, Paul M, et al. (2015) Vasopressors for the treatment of septic shock: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 10: 0129305.

- Sebbane M, Claret P, Lefebvre S, Mercier G, Rubenovitch J, et al. (2013) Predicting peripheral venous access difficulty in the emergency department using body mass index and a clinical evaluation of venous accessibility. J Emerg Med 44: 299-305.

- Freel AC, Shiloach M, Weigelt JA, Beilman GJ, Mayberry JC, et al. (2008) American college of surgeons guidelines program: A process for using existing guidelines to generate best practice recommendations for central venous access. J Am Coll Surg 207: 676-682.

- Bodenham CA, Babu S, Bennett J, Binks R, Fee P, et al. (2016) Association of anaesthetists of great britain and Ireland: Safe vascular access 2016. Anaesthesia 71: 573-585.

- O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, Garland J, et al. (2011) Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. American Journal of Infection Control 52: 162-193.

- Bellazzini MA, Rankin PM, Gangnon RE, Bjoernsen LP (2009) Ultrasound validation of maneuvers to increase internal jugular vein cross-sectional area and decrease compressibility. Am J Emerg Med 27: 454-459.

- Samy Modeliar S, Sevestre MA, de Cagny B, Slama M (2008) Ultrasound evaluation of central veinsin the intensive care unit: Effects of dynamic manoeuvres. Intensive Care Med 34: 333-338.

- Kost SI (2008) Ultrasound-assisted venous access. In: King C, Henretig FM (eds.). Textbook of pediatric emergency procedures. (2nd edn), Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA.

- Parry G (2004) Trendelenburg position, head elevation and a midline position optimize right internal jugular vein diameter. Can J Anaesth 51: 379-381.

- Kornbau C, Lee KC, Hughes GD, Firstenberg MS (2015) Central line complications. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci 5: 170-178.

- Pillai L, Zimmerman P, d’Audiffret A (2011) PS170. Inadvertent great vessel arterial catheterization during ultrasound-guided central venous line placement: A potentially fatal event. Journal of Vascular Surgery 53: 74.

- Fisher NC, Mutimer DJ (1999) Central venous cannulation in patients with liver disease and coagulopathy--a prospective audit. Intensive Care Med 25: 481-485.

- No authors listed (1999) The clinical anatomy of several invasive procedures. American Association of Clinical Anatomists, Educational Affairs Committee. Clin Anat 12: 43-54.

Citation: Portalatin ME, Fakhoury E, Brancato R, Willis SD, Rebein BH, et al. (2019) Factors Contributing to Unsuccessful Central Line Placement in the Neck and Chest. J Surg Curr Trend Innov 3: 015.

Copyright: © 2019 Manuel E Portalatin, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.