Factors Socio-Economic Data of Patients who Underwent a Cesarean Section in the Health District of Commune 5 of The District of Bamako in Mali

*Corresponding Author(s):

Bocoum AmadouDepartment Of Gynecology And Obstetrics, Gabriel TOURE University Hospital, Bamako, Mali

Tel:+223 00223760259,

Email:abocoum2000@yahoo.fr

Abstract

Introduction: According to the World Health Organization (WHO), while maternal mortality rates have declined worldwide since 1990, approximately 275,000 women die each year in childbirth, and nearly half of them live in sub- Saharan Africa. These are often poor, uneducated women or women living in rural areas: they have less access to institutionalized childbirth services.

Objectives: To specify the socio-demographic aspects of patients who underwent cesarean sections. To determine whether the implementation of this policy of free cesarean sections has been able to significantly reduce pre-existing inequalities in access to emergency obstetric care, including cesarean sections, in the Commune V Health District.

Patients and methods: The study took place in the Commune V Health District of Bamako, from February to September 2023. It focused on women who had undergone cesarean sections and was based on five socio-economic indicators out of the fifteen indicators mentioned in the various editions of the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) of Mali. These socio-economic data were processed using SPSS and Excel and converted to STATA for analysis in the United States of America (USA) through the National Technical Assistance Plus (NTA) program.

Results: During the study period, we performed 624 cesarean sections out of a total of 5,856 deliveries, representing a hospital rate of 10.65%. The sample consisted primarily of very wealthy women (459, 73.6%) and wealthy women (119, 19.1%). Analysis of the socioeconomic status of the indicators studied showed that women of high socioeconomic status (wealthy and very wealthy) benefited more from the free cesarean section politics compared to women from disadvantaged social groups, i.e., the very poor and poor.

Conclusion: The politics of exempting cesarean section fees in the Health District of Commune V of Bamako benefits women of high socio-economic status (very rich and rich) more.

Keywords

Cesarean Section; Free of Charge; Socio-Economic Data

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), while maternal mortality rates have declined worldwide since 1990, approximately 275,000 women die each year in childbirth, and nearly half of them live in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. These are often poor, uneducated, or rural women, who have less access to institutionalized childbirth services [1]. This inequality is also reflected in access to cesarean sections, even though this surgical procedure can save the lives of mothers and their children when performed in a timely manner [1]. In these Central and West African countries, less than 1% of the poorest women in rural areas receive a cesarean section. This figure is far below the need (3.6% to 6.5%). Conversely, eight of these countries had a cesarean section rate exceeding 4% among wealthy, urban women [1]. Maternal mortality remains high in Mali even though a downward trend has been observed in recent decades. Indeed, in 2006, this maternal mortality was 464 per 100,000 live births (LB); 368 per 100,000 LB in 2012-2013 and 325 per 100,000 LB in 2018 [2-4].

With the ultimate goal of reducing maternal and neonatal mortality, many countries have recently adopted innovative financing mechanisms to encourage the use of health services. These mechanisms include the elimination or subsidization of fees for certain procedures, such as cesarean sections. This option is generally implemented with the support of technical and financial partners [5]. For example, on June 23, 2005, the government of Mali decided to cover the costs associated with cesarean sections in public hospitals, district health centers, municipalities within the Bamako District, and military health service facilities. The objective of this decision was to make emergency obstetric care accessible to all pregnant women with a clinical need for cesarean delivery in order to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality. The objective of this study was to determine whether the implementation of this politics of free cesarean sections in the Health District of Commune V has been able to further reduce pre-existing inequalities in access to childbirth care and particularly cesarean sections.

Patients and Methods

We conducted a prospective descriptive study in the Commune V Health District of Bamako from February to September 2023. All patients who underwent a cesarean section in our department and agreed to participate after signing a pre- established informed consent form were included. The study focused on five socioeconomic indicators: the type of flooring in the home, the presence of a bicycle in the family, the presence of a television in the family, the source of drinking water consumed in the family, and the type of cooking fuel used in the family. Cesarean sections performed in our department but who declined to participate were excluded. We collected and then analyzed the socioeconomic data of women who benefited from exemption (free access) to cesarean section fees. Socio-economic status was determined using the poverty quintile approach on a scale of one hundred (100) points, based on the following elements as reported in the various editions of the Demographic and Health Surveys of Mali [2-4]:

1-20 points = very poor

21-40 points = poor

41-60 points = average to wealthy

61-80 points = rich

81-100 points = very rich

Interviews and document reviews were the data collection techniques used. The Local Health Information System (LHIS) officer and the cesarean section focal point, assisted by two medical students in their doctoral year, collected socioeconomic data from women before their hospital discharge. Semi-structured interview guides were used to gather socioeconomic data from women who had undergone cesarean sections. A data collection grid was used to extract sociodemographic characteristics from the medical records of women who had undergone cesarean sections. This socioeconomic data was processed using SPSS and Excel and converted to STATA for analysis in the United States of America (USA) through National Technical Assistance Plus (NTA).

Ethical considerations

The research protocols and survey tools were approved by the National Ethics Committee for Health and Life Sciences (CNESS) of Mali and the Ethics Committee of Abt (Abt: Associates Institutional) . Review (Board). Everyone associated with this study signed an agreement to maintain confidentiality and anonymity regarding the information collected. All study participants were asked to provide written and signed informed consent before the interview. Patients were free to decline, participate, or withdraw from participation. The researchers read the information provided on the consent form in French and the local language. The consent form emphasized the voluntary nature of participation and specified that the information collected would be kept strictly confidential. All information collected was anonymized before analysis.

Results

- Frequency: During the study period, we performed 624 cesarean sections out of a total of 5856 deliveries, representing a hospital frequency of 10.65%.

- Overall socio-economic data of the patients: The study population consisted of the very poor 9 (1.4%); the poor 6 (1%); the middle class 31 (4.9%); the rich 119 (19.1%); and the very rich 459 (73.6%).

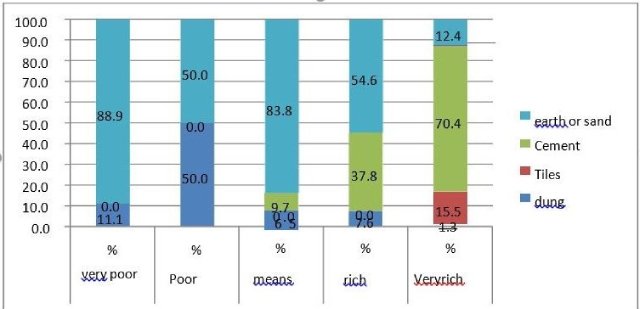

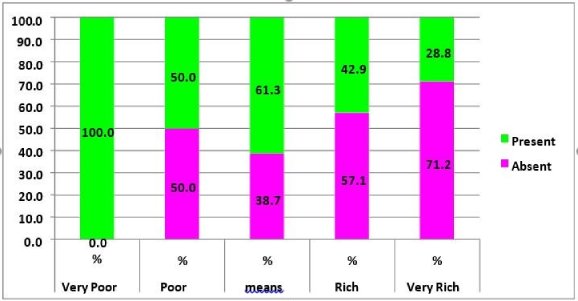

- Factors determining the socioeconomic level of Caesarean women (Figures 1-3)

Figure 1: Floor coverings in the households of women who have undergone cesarean sections.

Figure 1: Floor coverings in the households of women who have undergone cesarean sections.

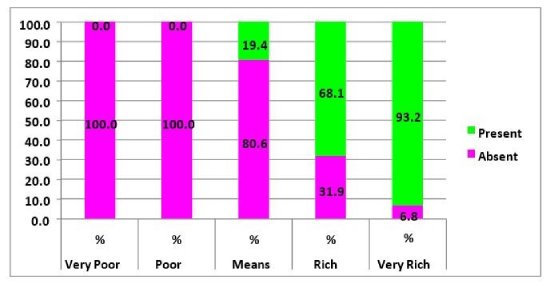

Figure 2: Presence of a bicycle in the households of women who had undergone a cesarean section.

Figure 2: Presence of a bicycle in the households of women who had undergone a cesarean section.

Figure 3: Presence of a television in the households of women who had undergone a cesarean section.

Figure 3: Presence of a television in the households of women who had undergone a cesarean section.

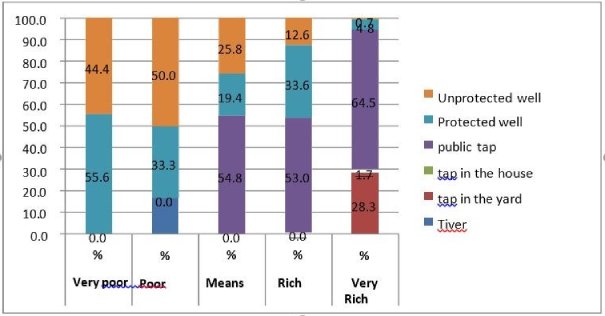

Figure 4: Drinking water in the households of women who have had a cesarean section.

Figure 4: Drinking water in the households of women who have had a cesarean section.

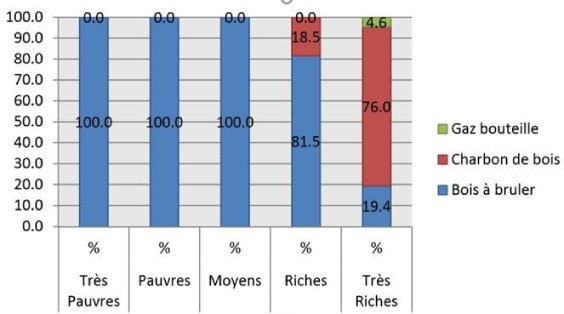

Figure 5: Fuel used in the households of women who have had a cesarean section.

Figure 5: Fuel used in the households of women who have had a cesarean section.

Discussion

During the study period, we performed 624 cesarean sections out of a total of 5856 recorded deliveries, representing a hospital cesarean section rate of 10.65%. This same cesarean section rate of 10.65% was found in a study conducted in Lubumbashi in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) [6]. In a study conducted in Benin at the Ouidah District Hospital (HZO), the authors reported a cesarean section rate of 2.38% in 2009 to 3.48% in 2011, representing an increase of 1.1 percentage points [7]. The increase in the cesarean section rate observed over the last three decades in developed countries has been accompanied by a proportional benefit for the mother-child dyad, namely a dramatic decrease in maternal and perinatal mortality [7]. This is as these authors report that for cesarean section rates above 20%, maternal mortality and perinatal mortality from 1990 to 2013 increased [8-10]:

- from 7.4 to 4.8 per 100,000 live births and from 4.4 to 2.6‰ in Denmark;

- from 10.3 to 3.2 per 100,000 live births and from 4.6 to 2.3‰ in Austria;

- from 10.4 to 6.1 per 100,000 live births and from 4.5 to 2.7‰ in England;

- and from 15.6 to 8.8 per 100,000 live births and from 3.6 to 2.3‰ in France

Free cesarean sections in low-resource African countries have been accompanied by improved access to care, including cesarean sections, for disadvantaged populations. For example, the cesarean section rate at the Ouidah District Hospital (HZO) increased from 2.38% in 2009 to 3.48% in 2011 [11]. An increase in the cesarean section rate is one of the expected outcomes of this type of initiative. This increase has also been reported in Senegal and Ghana [12,13]. In Ghana, Witter found that in the Gomao district , the cesarean section rate increased from 1.4% in 2002 to 2.6% in 2004 [12].

In Mali, this rate increased from 0.9% in 2005 to 2.3% in 2009 [14]. These rates remain disparate and vary from one region to another. These estimates fell short of the 4% target set for 2008 by the Health and Social Development Program (PRODESS) II [14]. Analysis of the overall socioeconomic level showed that the majority of the sample consisted of the very wealthy (459, 73.6%) and the wealthy (119, 19.1%). The national survey revealed that in Mopti (Mali's fifth administrative region), 58.9% of women who underwent cesarean sections were from low socioeconomic backgrounds, comprising the very poor and the poor [14]. In our survey, the very poor and the poor, for whom the exemption from fees related to cesarean sections (free cesarean sections) had been implemented, represented only 1.4% and 1% of the sample, respectively. The middle-income group represented 4.9% of our sample. In Mali, a national survey reported that 23.9% of women who gave birth by cesarean section in public sector health facilities were from a low socioeconomic background, compared to 48.8% of those belonging to the high socioeconomic group [14]. Women from a low socioeconomic background represented 11.4% of women who underwent cesarean sections in hospitals and 26.9% in Referral Health Centers (CSRéf ). At the hospital level, 63.2% of cesarean sections were performed on women from a high socioeconomic background, compared to 45.5% in CSRéf [14-16]. In our study, the flooring of the very poor consisted of 8.9% earth or sand and 11.1% animal dung, while 37.8% of the wealthy and 70.4% of the very wealthy had cement flooring. Also, 15.5% of the flooring of the very wealthy consisted of tiles. Flooring is a marker of affluence and social well-being. Thus, only women of high socioeconomic status could afford tiled floors. During our study, bicycles were present in the households of all the very poor women (100%) and 50% of the poor. Only 42.9% of the wealthy and 28.8% of the very wealthy owned a bicycle. The bicycle as a means of production is much more useful for the lower social classes (the poor and the very poor).

No women in the lowest socioeconomic categories (very poor and poor) owned a television in their household during our study, while 8.1% of the wealthy and 93.2% of the very wealthy owned at least one television in their household. In our sample, 44.4% of the very poor and 50% of the poor used unprotected well water for drinking in their households, while 55.6% of the very poor and 33.3% of the poor used protected well water. More than half of the women in the highest socioeconomic categories—53% of the wealthy and 64.5% of the very wealthy— used the public tap for drinking water. According to the Mali Demographic and Health Survey VI 2018 (DHS-M) [14], 51% of urban households use tap water, while 27% of rural households use protected well water. Women in the highest socioeconomic categories (73% of the very wealthy) used charcoal as their fuel, while 19.4% of the very wealthy used firewood. Butane gas was used by 4.6% of the very wealthy. Women in the lowest socioeconomic categories (very poor and poor) used only firewood as their fuel.

Ultimately, this study conducted in Commune V of the Bamako District shows that it is the very wealthy who benefit most from the policy of free cesarean sections. This indicates that the policy has not yet achieved its primary objective in this commune, which is one of the most disadvantaged in Bamako. Originally, this policy was intended to reach all social strata, particularly the most vulnerable, namely the poor and the very poor. The free cesarean section policy is a good initiative, but we know that cesarean sections are only available to women who have access to healthcare facilities staffed with qualified personnel. These are likely the very wealthy, who have easier access to quality care in better-equipped facilities with sufficiently qualified staff. The very poor remain in their communities and do not have access to healthcare, including cesarean sections. For a woman needing a cesarean section to receive one, she must have access to qualified healthcare personnel in a facility equipped to perform them. The poor and very poor have limited access to such facilities. The policy of free cesarean sections, as implemented, has not been able to reduce the existing gap between disadvantaged and privileged social groups regarding access to cesarean sections. Our conclusion is far from being unanimously accepted in the literature. For example, in 2005 and 2009 respectively, Benin and Mali, countries with very high maternal mortality rates (405 and 587 per 100,000 live births), chose to make cesarean sections free of charge. Based on three demographic and health surveys covering a 15-year period for both countries, Dumont et al., [1] sought to verify whether these measures had reduced inequalities. In their initial analyses, these authors had already shown that free healthcare policies had improved access to care by increasing the percentage of women who gave birth in health facilities in general, and who had access to cesarean sections in particular. However, while inequalities did not widen, they largely persisted, except in Mali, between the most educated and least educated women [1]. Thus, in Benin, the authors assert that the components of free healthcare are not all applied in hospitals, as is the case with the transfer of women to the hospital, an essential step for accessing care. The failure to take into account this service has been noted in most countries which apply free cesarean sections, even though it constitutes one of the major obstacles to access to care [14-16].

To effectively achieve these objectives, the political and municipal authorities of Commune V must make efforts within the community to improve access to health centers for the most vulnerable segments of the population, namely the poor and the very poor. This will involve support measures aimed at eliminating the first two delays (delay in seeking care and delay in accessing healthcare services). According to Dumont A et al., [17], these support measures are necessary to counteract the unintended or perverse effects of free cesarean sections in sub- Saharan Africa, linked to a real risk of overuse of services by the wealthiest. In Kayes (Mali), none of these policies initially included support measures to simultaneously improve the quality of obstetric care, a crucial condition for effectively reducing maternal and neonatal mortality. Furthermore, the costs associated with transporting patients from the community to the referral hospital are generally not covered by these subsidy programs. It is therefore unlikely that the poorest women, residing far from health facilities, will be able to benefit from the advantages of these free policies.

Conclusion

The policy of exemption from cesarean section fees decreed by the government of the Republic of Mali on June 23, 2005, benefits women of high socio - economic level (very rich and rich) more in commune V of the district of Bamako. In order to address this deficiency, we make the following recommendations to the political, administrative, health, municipal, and religious authorities of Commune V:

- Encourage midwives to go into the community to talk about the benefits of prenatal care and the free nature of cesarean sections;

- (Within the framework of the evacuation referral) of pregnant women from the community to health facilities;

- To make ambulances available to facilitate access to healthcare facilities for disadvantaged patients.

- Involving local opinion leaders in the management of the health of the population of Commune V.

- Use the various community communication channels (community radio station, traditional communicators, social development agents, message via telephone company) for a wide dissemination of this policy of free cesarean section within the commune V

References

- Dumont A (2018) Free cesarean sections: more access, but no less inequality - IRD le Mag. International Journal for Equity in Health.

- Demographic and Health Surveys Program (DHS) (2006) Mali Demographic and Health Survey 2006. Calverton, DHS, Maryland, USA.

- The World Bank (2013) Demographic and Health Survey in Mali 2012-2013. The World Bank, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

- USAID (2018) Mali: 2018 Demographic and Health Survey. USAID, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

- Ouedraogo TL, Kpozehouen A, Gléglé-Hessou Y, Makoutodé M, Saizonou J, et al. (2013) [Evaluation of free cesarean sections in Benin]. Sante Publique 25: 507-515.

- Ministry of Health, National Health Directorate (DNS) (2005) Guide for the implementation of cesarean section by decree No. 05-350/P-RM. DNS.

- Kinenkinda X, Mukuku O, Chenge F, Kakudji P, Banzulu P, et al. (2017) [Cesarean section in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo I: frequency, indications and maternal and perinatal mortality]. Pan Afr Med J 27: 72.

- Mongbo V, Godin I, Mahieu C, Ouendo EM, Ouédraogo L (2016) Cesarean section in the context of free healthcare in Benin. Public Health 28: 399-407.

- Rozenberg P (2004) [Evaluation of cesarean rate: A necessary progress in modern obstetrics]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 33: 279-289.

- World Health Organization (2012) UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank: Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- UNICEF, WHO, The World Bank, United Nations Population Division (2015) The Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME) Levels and Trends in Child Mortality. Report 2013. UNICEF, New York, USA.

- Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, Shackelford KA, Steiner C, et al. (2014) Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990-2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 384: 980-1004.

- Richard F, Witter S, De Brouwere V (2010) Innovative approaches to reducing financial barriers to obstetric care in low-income countries. Am J Public Health 10: 1845-1852.

- Abt associates (2011) Improving access to life saving maternal health services : the effects of removing user fees for caesareans in Mali. Abt associates, Bamako, Mali.

- Richard F, Ouedraogo C, De Brouwere V (2008) Quality cesarean delivery in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso: A comprehensive approach. Int J Gynecol Obstet 103: 283-290.

- Kouéta F, Ouédraogo Yugbaré SO, Dao L, Dao F, Yé D, et al. (2011) [Medical audit of neonatal deaths with the "three delay" model in a pediatric hospital in Ouagadougou]. Sante 21: 209-214.

- Dumont A, Ridde V, Ouattara F (2015) Free cesarean sections accelerate the reduction of maternal and neonatal mortality in Africa. Misconceptions in global health. EHESP, Montréal, Canada.

Citation: Oumar TS, Amadou B, Ousmane KI, Alassane T, Seydou F, et al., (2026) Factors Socio-Economic Data of Patients who Underwent a Cesarean Section in the Health District of Commune 5 of The District of Bamako in Mali. HSOA J Reprod Med Gynaecol Obstet 11: 210.

Copyright: © 2026 Traoré Soumana Oumar, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.