False Positive ANA Testing in the Setting of Hypovitaminosis D

*Corresponding Author(s):

Philip V PeplowDepartment Of Anatomy, University Of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

Tel:+64 9 534 6224,

Fax:+64 3 479 7254

Email:phil.peplow@otago.ac.nz

Abstract

Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with autoimmune diseases, which include systemic lupus erythematosus, and may affect the outcome and activity of these diseases that result from aberrant activation of the immune system. Patients with the systemic autoimmune diseases may have a positive blood test for Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA). The ANA test is very sensitive for the diagnosis of autoimmune diseases but results in many false positives. It has been reported that up to 15% of completely healthy individuals have a positive ANA test without an autoimmune disease and that ANAs are measurable in approximately 25% of the population. Only about 10-13% of persons with a positive ANA test are found to have lupus. Vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency is prevalent in patients with autoimmune disease and vitamin supplementation has a therapeutic effect on disease severity and progression. Though there are many studies supporting the clinical picture that lupus patients are more prone to vitamin D deficiency, there are only a few articles that have considered the possibility that hypovitaminosis D is associated with false positive ANA testing. A case of an anemic patient who was initially evaluated and managed as a case of lupus is presented.

Keywords

Anemia; Antinuclear antibody; Autoimmune disease; Case study; Vitamin D

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with autoimmune diseases such as type 1diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, Crohn’s disease, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), and may affect the outcome and activity of these diseases that result from aberrant activation of the immune system. Supplementation with vitamin D (as cholecalciferol), which hasproven immunomodulatory properties, has been used to decrease disease severity or enhance the therapeutic effect of current medication [1]. Lupus patients are usually photosensitive and have a high risk of developing vitamin D deficiency due to avoidance of sunlight and use of sunscreens and protective clothing. While low levels of vitamin D may be involved in SLE etiology, it could be the result and not the cause of the disease [2]. Patients with the following systemic autoimmune diseases may have a positive blood test for Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA): SLE, scleroderma, Sjögren’s syndrome, mixed connective tissue disease, drug-induced lupus, polymyositis/dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, oligoarticular juvenile chronic arthritis, polyarteritis nodosum. Patients with organ-specific autoimmune diseases may also have a positive test for ANA. These diseases include thyroid diseases, gastrointestinal diseases, pulmonary diseases. In addition, patients with infectious diseases may test positive for ANA [3]. Moreover, some medications can cause a positive ANA, and other conditions such as cancer can cause a positive ANA [4].

The ANA test is very sensitive for the diagnosis of autoimmune diseases but results in many false positives. It has been reported that up to 15% of completely healthy individuals have a positive ANA test without an autoimmune disease and that ANAs are measurable in approximately 25% of the population [5]. Only about 10-13% of persons with a positive ANA test are found to have lupus. A dilution of 1:160 increases the specificity of the ANA test for the diagnosis of autoimmune diseases, and at this dilution only 5% of normal individuals have a positive ANA test [6].

We present the case of a young woman aged 30 years who presented to the clinic with fatigue as well as difficulty concentrating and was tested for ANA antibodies as part of a workup for possible SLE. However, apart from iron deficiency anemia, this woman did not have and had not had in the past any additional symptoms of SLE. It has been reported that patients need at least 4 of 11 criteria, either at the presenting time or at some time in the past, to be diagnosed as having SLE. These are malar rash, discoid rash, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, arthritis, serositis, kidney disorder, neurological disorder (seizures or psychosis), blood disorder (anemia, leukopenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia), immunologic disorder (anti-DNA or anti-Sm or positive antiphospholipid antibodies), abnormal ANA [7].

After testing positive for ANA, the patient underwent an extensive workup for autoimmune causes that could account for her fatigue. Vitamin D levels were also assessed and after normalization the patient subsequent tested negative for ANA, both in titers and specking pattern. The findings raise the possibility that low vitamin D may interfere with and could cause a false positive test for ANA in healthy individuals [8], suggesting that low vitamin D levels need to be corrected before carrying out an ANA test.

CASE REPORT

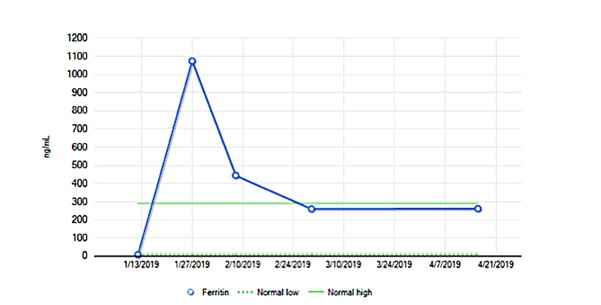

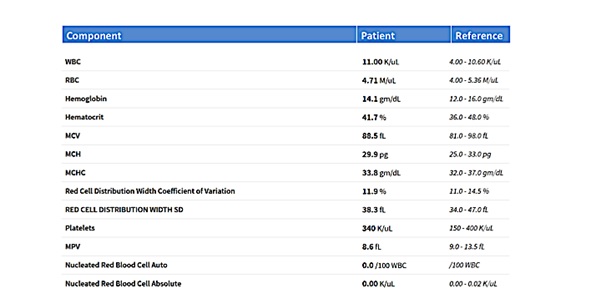

Herein we report on athirty-year-old female patient who presented with generalized fatigue, pale skin, and insomnia. The results of a CBC test were unremarkable apart from a slight rise in WBCs (Table 1). Measurement of blood iron levels gave a value of 7.4 mg ferritin/ml (on 1/12/19). The patient was started on i.v. infusions of ferritin that raised the levels to 1074.3 (1/27/19), 445.6 (2/8/19), 260.1 (3/1/19) and 262.1 mg ferritin/ml (4/16/19) (Figure 1). Anemia due to blood losses, which is common in premenopausal women, was ruled out with patient history. To assess the cause of the iron-deficiency anemia, and the underlying pathology behind the low levels of hemoglobin, blood antibody tests were performed to determine whether the patient had an autoimmune disease such as connective tissue disorder (e.g. crest syndrome), Systemic Erythematous Lupus (SLE), or Sjogrens disease (Table 2).

Figure 1: Blood ferritin levels in the patient after starting i.v.infusions of ferritin.

Figure 1: Blood ferritin levels in the patient after starting i.v.infusions of ferritin.

Table 1: CBC test in the patient at presentation.

Table 1: CBC test in the patient at presentation.

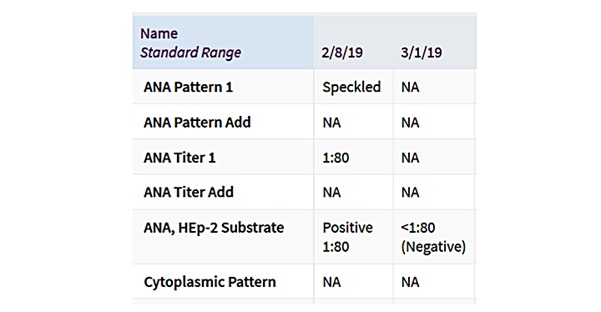

Table 2: Initial and retesting for ANA in the patient.

Table 2: Initial and retesting for ANA in the patient.

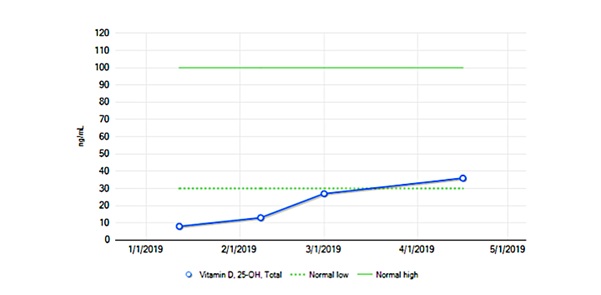

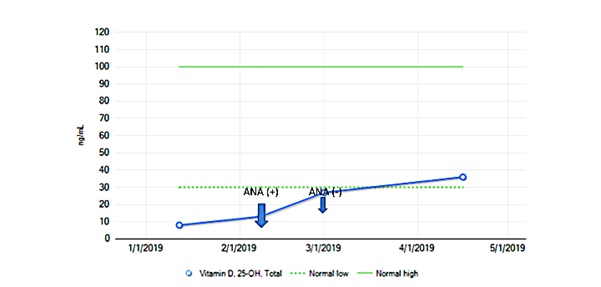

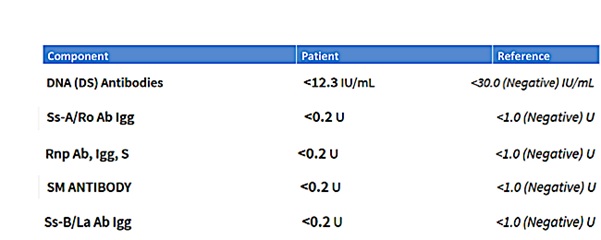

Also as vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency is prevalent in patients with autoimmune disease and vitamin supplementation has a therapeutic effect on disease severity and progression [9], blood vitamin D level was measured. The values were 8 (1/12/19), 13 (2/8/19), 27 (3/1/19) and 36 ng 25-OH vitamin D/ml (4/16/19). ANA testing was done both before (2/8/19) and after (3/1/19) vitamin D levels were normalized (Figures 2&3). The patient was retested for ANA (3/1/19) and other antibodies and which were negative (Tables 2&3).

Figure 2: Blood levels of 25-OH vitamin D in the patient with respect to normal low and normal high levels.

Figure 2: Blood levels of 25-OH vitamin D in the patient with respect to normal low and normal high levels.

Figure 3: Blood levels of 25-OH vitamin D in the patient showing times when positive and negative ANA test results were found.

Figure 3: Blood levels of 25-OH vitamin D in the patient showing times when positive and negative ANA test results were found.

Table 3: Testing for other antibodies at the time of retesting for ANA.

Table 3: Testing for other antibodies at the time of retesting for ANA.

METHODS

Collection of peripheral blood samples: Blood was collected from the left cubital vein into EDTA-coated tubes without complications and stored appropriately prior to analysis. Collected blood was sent to and analyzed by Mayo Clinic Laboratories located at Rochester Superior Drive in Rochester, MN 55901.

DISCUSSION

Relationship between levels of vitamin D and its effects on ANA testing

Vitamin D can be absorbed from the outside environment via two main routes, the first being through diet and the second through synthesis after UVB exposure [10,11]. Early observations include a lower risk of autoimmunity associated with living closer to the equator as well as a number of specific cases and meta-analysis showing an increase in prevalence in autoimmune conditions in individuals with hypovitaminosis D [12-15]. This relationship is likely due to both extrinsic and intrinsic factors, for example, the photosensitivity in SLE patients consequently leads to an avoidance and hence low sun exposure, while lupus nephritis may disrupt the hydroxylation of vitamin D to 25-hydroxy vitamin D [16]. However, a more recent and intriguing finding is the association of not just hypovitaminosis D and a correctly diagnosed SLE, but the prevalence of a false positive ANA result in those patients that present concurrently with hypovitaminosis D [17]. Though it is clear that properly diagnosed patients with SLE do have a higher incidence of hypovitaminosis D, this case highlights the importance of co-screening for vitamin D levels even before ANA testing in patients with a low negative predictive value for autoimmune conditions. Though there are many studies supporting the clinical picture that SLE patients are more prone to vitamin D deficiency, there are only a few articles that have considered the possibility that hypovitaminosis D is associated with false positive ANA testing, most of which concluded that further immunological research needs to be performed. One study, for example, showed a correlation between vitamin D levels in an SLE patient and the level of B lymphocyte activation which causes increased autoantibodies, potentially affecting the validity of ANA testing in those who are deficient in vitamin D [8]. This specific study assessed serum samples from 32 European American female patients and found that vitamin D deficiency was associated with an increased autoimmune response in healthy individuals as well as in patients with SLE. The authors isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells, which were subsequently tested for intracellular phospho-ERK 1/2 as a measure of B cell activation status [8]. It has been shown that vitamin D also regulates the activity of CD4 T cells and Th1/Th2 mediated activity, likely explaining its capacity to prevent inflammation and autoimmunity [16,18]. Another article highlighted that vitamin D is an important mediator in immune function, and when deficient, may be a main contributor in the development of autoimmune antibodies and may be able to be used as a sign of immune dysfunction. The authors noted a linear relationship wherein patients with severe vitamin D deficiency demonstrated 2.99 increased in odds of receiving a positive ANA test, while those patients that were deficient and insufficient had just twice the increase in odds of a positive ANA [19]. If, however, low vitamin D perpetuates false positive ANA testing through an immunological response, we would expect to see false positive testing in ANA testing that is not necessarily associated with SLE workup. One study, determining the connection between vitamin D and ANA in inflammatory bowel disease patients, for example, showed vitamin D has a regulatory effect on B lymphocytes and immunoglobulins, increasing ANA synthesis in patients with vitamin D deficiency. The study concluded that low levels of vitamin D are a risk factor for ANA formation. It is evident that immunomodulation by vitamin D suppresses the development of an autoimmune response in various diseases [17].

CONCLUSION

In the case we have presented here, the patient was screened for SLE with an ANA test without regard to vitamin D assessment and correction first. The false positive was followed up with extensive, expensive, time consuming and emotionally stressful testing to confirm a possible SLE diagnosis. The case here supports other additional peer-revised studies that validate the relationship between false positive ANA testing and hypovitaminosis D likely due to immunomodulation. SLE and hypovitaminosis D both present with a strikingly similar and overlapping clinical picture; however, given that low vitamin D is much more population prevalent, even in sufficiently sun exposed patients, it is suggested by this and other case studies that vitamin D levels be measured and subsequently treated if necessary before screening for autoimmune conditions such as SLE is begun. Additionally, treatment of hypovitaminosis D in true SLE patients modulates and ameliorates SLE symptoms, and would be treated in SLE patients, nonetheless, adding more credence and value to a more cost effective and less emotional toll-taking clinical pathway.

REFERENCES

- Dankers W, Colin EM, van Hamburg JP, Lubberts E (2016) Vitamin D in autoimmunity: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Front Immunol 7: 697.

- Hassanalilou T, Khalili L, Ghavamzadeh S, Shokri A, Payahoo L, et al. (2017) Role of vitamin D deficiency in systemic lupus erythematosus incidence and aggravation. Auto Immun Highlights 9: 1.

- Betancur JF, Londoño A, Estrada VE, Puerta SL, Osorno SM, et al. (2018) Uncommon patterns of antinuclear antibodies recognizing mitotic spindle apparatus antigens and clinical associations. Medicine (Baltimore) 97: 11727.

- Dinse GE, Parks CG, Meier HC, Co CA, Chan EK, et al.(2018) Prescription medication use and antinuclear antibodies in the United States, 1999-2004. J Autoimmun 92: 93-103.

- Li Q-Z, Karp DR, Quan J, Branch VK, Zhou J, et al. (2011) Risk factors for ANA positivity in healthy persons. Arthritis Res Ther 13: 38.

- Satoh M, Vázquez-Del Mercado M, Chan EK (2009) Clinical interpretation of antinuclear antibody tests in systemic rheumatic diseases. Mod Rheumatol 19: 219-228.

- Fava A, Petri M (2019) Systemic lupus erythematosus: Diagnosis and clinical management. J Autoimmun 96: 1-13.

- Ritterhouse LL, Crowe SR, Niewold TB, Kamen DL, Macwana SR, et al. (2011) Vitamin D deficiency is associated with an increased autoimmune response in healthy individuals and in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 70: 1569-1574.

- Yang C, Leung PS, Adamopoulos IE, Gershwin ME (2013) The implication of vitamin D and autoimmunity: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 45: 217-226.

- Borel P, Caillaud D, Cano NJ (2015) Vitamin D bioavailability: State of the art. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 55: 1193-1205.

- Silva MC, Furlanetto TW (2018) Intestinal absorption of vitamin D: A systematic review. Nutr Rev 76: 60-76.

- Reichrath J (2006) The challenge resulting from positive and negative effects of sunlight: how much solar UV exposure is appropriate to balance between risks of vitamin D deficiency and skin cancer? Prog Biophys Mol Biol 92: 9-16.

- Göring H, Koshuchowa S (2016) Vitamin D deficiency in Europeans today and in Viking settlers of Greenland. Biochemistry (Mosc) 81: 1492-1497.

- Wang J, Lv S, Chen G, Gao C, He J, et al. (2015) Meta-analysis of the association between vitamin D and autoimmune thyroid disease. Nutrients 7: 2485-2498.

- Illescas-Montes R, Melguizo-Rodríguez L, Ruiz C, Costela-Ruiz VJ (2019) Vitamin D and autoimmune diseases. Life Sci 233: 116744.

- Cyprian F, Lefkou E, Varoudi K, Girardi G (2019 Immunomodulatory effects of vitamin D in pregnancy and beyond. Front Immunol 10: 2739.

- Santos-Antunes J, Nunes AC, Lopes S, Macedo G (2016) The relevance of vitamin D and antinuclear antibodies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease under anti-TNF treatment: A prospective study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 22: 1101-1106.

- Trombetta A, Paolino S, Cutolo M (2018) Vitamin D, inflammation and immunity: review of literature and considerations on recent translational and clinical research developments. The Open Rheumatology Journal 12: 201-213.

- Meier HC, Sandler DP, Simonsick EM, Parks CG (2016) Association between vitamin D deficiency and antinuclear antibodies in middle-aged and older U.S. adults. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 25: 1559-1563.

Citation: Martinez B, Harker DM, Robinson A, Peplow PV (2020) False Positive ANA Testing in the Setting of Hypovitaminosis D. J Clin Stud Med Case Rep 7: 098.

Copyright: © 2020 Bridget Martinez , et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.