Frequency and Predictors for the Use of Complementary Medicine among Gynecological Cancer Patients

*Corresponding Author(s):

Wiedeck C#Department Of Obstetrics And Gynecology, Technical University Munich, Germany

Email:clea_wiedeck@yahoo.de

# Equal contribution

Abstract

Background: Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) use is common among cancer patients. CAM use has been shown to correlate with a younger age, a higher level of education and higher income. However, CAM use and its predictors in patients with gynecological cancer currently remain unclear. The purpose of this study was to determine the frequency and predictors of CAM use and to investigate factors that might influence the use of CAM.

Methods: The survey was a pseudonymous questionnaire that was conducted on 141 gynecological cancer patients from January 2014 to May 2014 via a telephone interview. The questionnaire was developed for this study and included three separate parts which researched clinical data/sociodemographic data (25 questions), use of complementary medicine (47 questions) and change of lifestyle factors after the diagnosis of cancer (39 questions). Eligible participants were women with gynecological cancer (n=291) who had undergone surgery at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Technical University Munich, Germany, from 2011-2013. Descriptive statistics were generated to determine patterns of CAM use. Univariable analysis was used to detect patient characteristics associated with an interest in different CAM therapies.

Results: When comparing CAM users to non-CAM users, there was a statistically significant association between CAM use and a younger age (p <0.01), being in a stable relationship (p = 0.011), a normal BMI (p = 0.04) and a higher educational level (p = 0.001). 96% (n = 79) of the CAM users hoped that CAM would directly treat cancer. The desire for psychological and physical relief in terms of an improvement in the quality of life was stated in 91% (n = 75). 89% (n = 73) hoped to further enhance the effects of the conventional oncological treatment, and 65% (n = 53) sought an alleviation of the side effects of the conventional therapy.

Only 2% used the CAM therapy as an alternative to conventional medicine. 56% (n = 47) of CAM users considered their complementary therapies to be just as important as and 12% (n = 10) even more important than their conventional oncological treatments. 32% (n = 27) found CAM therapies to be of minor importance.

Conclusion: Our data demonstrates a high overall interest in CAM in patients with gynecological cancer. Health care professionals should be aware of this in order to be able to better address their patients´ needs. In the interest of the patients’ overall well-being and safety, it is necessary to explore the use of CAM with cancer patients, educate them about potentially beneficial therapies even in the light of the limited available evidence and to work towards an integrated model of health-care.

Keywords

Complementary Medicine; Gynecological cancer

ABBREVIATIONS

BMI: Body mass index

CAM: Complementary and alternative medicine

EU: European Union

NCCIH: National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health

SD: Standard deviation

TCM: Traditional Chinese Medicine

RDI: University hospital Rechts Der Isar

BACKGROUND

Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) use is common among cancer patients [1-5]. According to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), CAM treatments are classified into two subgroups: “natural products” (e.g., dietary supplements like herbs, vitamins, minerals and probiotics) and “mind and body practices” (e.g., yoga, chiropractic and osteopathic manipulations, meditation and massage therapy). However, some approaches may not fit into either of these groups, e.g. homoeopathy, Ayurveda medicine or traditional Chinese medicine [6].

Based on a European survey conducted by Molassiotis et al., about 36 % of all cancer patients in the European Union use CAM. Several studies have shown that the application of CAM is particularly common in breast and gynecological cancer patients with a prevalence of up to 90% [4,7-14].

The reasons for CAM use vary considerably and include strengthening the immune system and body, reducing side effects of conventional treatments, fighting cancer, detoxifying, reducing symptoms of psychological distress and being congruent with the patients’ beliefs [5,9,15,16].

In 2017, a cross-sectional study of 350 cancer patients found that the majority of CAM users (89.8%) considered CAM helpful, and that only 10.2% reported no benefit [5]. Fasching et al. showed that an overall deterioration of their health status was less common in CAM users (35.1%) than in non-users (50.1%), and that the use of CAM was associated with an improvement of family conditions (6%) compared to non-users (2 [9].

A correlation of the use of complementary therapies with a younger age, higher level of education, higher income, less physician consultations and the absence of metastases at the time of diagnosis has been described in various studies [5,10,15-19].

The primary purpose of this study was to assess the prevalence and predictors for the use of complementary medicine in patients with gynecological cancer. We sought to examine the reason for CAM use in order to gain additional information in this particular population group. This information will enable health care providers treating women with gynecological malignancies to better address their patients’ needs.

METHODS

From March 2014 to May 2014, the survey was conducted via telephone interviews with a structured pseudonymous questionnaire at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Technical University Munich, Germany.

Study population

The telephone interview was conducted with women who had undergone gynaecological cancer (ovarian, cervical, vulva, endometrial cancer) surgery at our hospital. Inclusion criteria were age above 18 years, the command of the German language and the mental capacity to understand the questionnaire. In total, 141 out of 291 patients participated in the study. After accounting for the patients who had deceased, the return rate was 59%.

Questionnaire

The survey questionnaire, developed in the German language, consisted of 111 items

- State of disease (metastases, recurrence and oncological treatment)

- Assessment of sociodemographic factors including age, education, marital status, employment and Body Mass Index (BMI)

- Assessment of personal opinions regarding CAM

- Health behaviours, lifestyle factors, nutritional habits and physical activity

Statistical analysis

Mean ± standard deviation was used to describe the distribution of quantitative data. Absolute and relative frequencies were used to present qualitative data. A hypothesis testing by t- and chi-squared tests was conducted to detect associations between Non-CAM use and patients´ sociodemographic characteristics and health behaviours. Our approach towards the data analysis was exploratory, without a specific a-priori hypothesis to prove. Hypothesis testing was therefore conducted on two-sided 5% significance levels. Data management and statistical analyses were performed using Excel and the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA).

RESULTS

The patients who participated in the study had a mean age of 62.0±11.6 years (±Standard Deviation (SD)). Patients who used CAM in the setting of the treatment of their malignant disease were significantly younger than patients who did not use CAM (mean 59± 11.1 years versus 67± 10.8 years, p<0.01). In addition, there was a significant association between the use of CAM and the presence of a partnership (married, relationship) (p=0.011). 43% of CAM users (n=86) and 61% (n=35) of the non-users were overweight based on their BMI. There was a statistically significant association between a normal weight based on the BMI and the use of CAM (p=0.04).

Table 1 shows the association between the use of CAM and the level of education, demonstrating an increasing amount of CAM users among gynecological cancer patients with a higher educational level. This association reached statistical significance (p=0.001).

|

Educational degree |

CAM use (n=84) |

No CAM use (n=57) |

|

Noeducationaldegree |

2 (50%) |

2 (50%) |

|

Primary school ±4 years |

10 (30%) |

23 (70%) |

|

Middle schooldiploma |

30 (67%) |

15 (33%) |

|

High schooldiploma |

42 (71%) |

17 (29%) |

Table 1: Educational level and the use of CAM techniques.

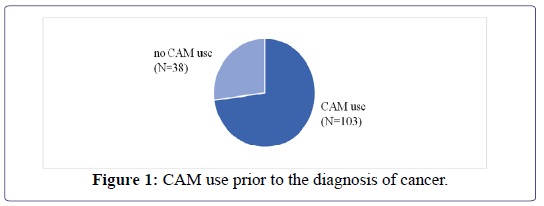

While the entire patient population displayed a high prevalence of religiosity and spirituality (78%, n=110), there was no significant correlation between a religious or spiritual faith and the use of CAM techniques (p=0.097) (Figure 1).

73% (n=103) of the patients had been using CAM methods prior to the diagnosis of cancer, 27% (n=38) had not previously used CAM. There was a significant correlation between a prior use of CAM and the use of CAM during the cancer diagnosis (p=0.037) (Table 2).

|

CAM therapies |

Frequency |

% |

|

Trace elements |

60 |

71% |

|

Vitamins |

54 |

64% |

|

Phytotherapy |

49 |

58% |

|

Homeopathy |

41 |

55% |

|

Anthroposophicalmedicine |

28 |

33% |

|

Nutritional supplements |

25 |

30% |

|

TCM (traditionell chinesische medicine) |

18 |

21% |

|

Healing tees |

18 |

21% |

|

Infusions to strengthen the immune system |

18 |

21% |

|

Energetichealing |

10 |

12% |

|

Detoxification |

10 |

12% |

|

Hyperthermia |

9 |

11% |

|

Schüssler salts |

8 |

10% |

|

Healing mushrooms |

8 |

10% |

|

Bach flowers |

7 |

8% |

|

Enzyme therapy |

4 |

5% |

|

Others |

13 |

15% |

Table 2: CAM therapies used in the study population.

The most frequently applied CAM treatment was the use of trace elements such as zinc, selenium and L-carnitine (n=60), followed by the use of vitamins (64%, n=54) and phytotherapy (58%, n=49). Homeopathic and anthroposophical medications, nutritional supplements and TCM treatments were also frequently used.

39% (n=33) of the patients initiated the CAM treatment during chemo- or radiotherapy. 24% (n=20) started using CAM post-operatively, 19% (n=16) after the completion of the conventional oncological treatment, 8% (n=7) in the setting of metastases or a recurrence, and 7% (n=6) with the primary diagnosis.

In terms of the frequency of the CAM use as well as compliance, only 8% of the patients (n=7) were non-compliant with treatment recommendations, translating to a CAM treatment compliance rate of 92% (Table 3).

|

Reasons |

Frequency |

% |

|

Recommendation, positive reports |

80 |

95% |

|

Activeinvolvement |

73 |

87% |

|

Holisticapproach |

72 |

86% |

|

Use of all potential treatments |

68 |

81% |

|

Convincedof CAM treatments |

64 |

76% |

|

Prevention and treatment of side effects of the conventional oncological treatment |

40 |

48% |

|

Information from books, radio, television, presentations |

33 |

39% |

|

Better medical treatment by CAM providers |

15 |

18% |

|

Loss of faith in conventional medicine |

5 |

6% |

|

Failureofconventionalmedicine |

5 |

6% |

Table 3: Reasons for the use of CAM.

Search for information on CAM

One part of the study focused on the questions of which CAM treatments were of particular interest and which type of media was used in order to gather information on CAM techniques. 93 patients (66%) claimed to have researched oncological CAM therapies on their own. 63% of the patients used medical literature (n=59), 61% physicians (n=57) and 49% different types of media (n=46) to learn about CAM. 26% (n=24) of the patients received recommendations from family members and friends. Fellow patients (n=18), medical associations (n=16) and naturopaths (n=8) were rarely used as a source of information.

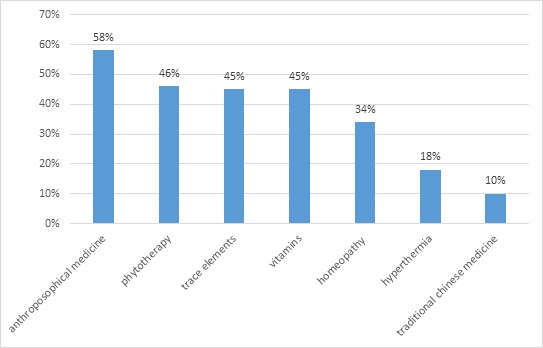

Patients reported a remarkable interest in anthroposophical medicine, phytotherapy, trace elements, vitamins and homeopathy (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Researched CAM therapies.

Figure 2: Researched CAM therapies.

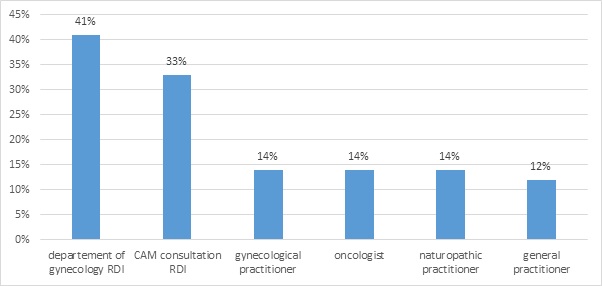

54% (n=76) stated that the use of CAM had been recommended to them in the setting of the diagnosis of cancer, most frequently by physicians (79% (n=59). Recommendations were also given by friends and family members (28%, n=21), followed by naturopaths 16% (n=12). 8% (n=6) received a recommendation to use CAM from medical support staff (physical therapists, osteopaths). “Physicians” were further analyzed in order to determine the exact source of information (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Different groups of physicians and the recommendation to use CAM.

Figure 3: Different groups of physicians and the recommendation to use CAM.

There was a highly significant correlation between a CAM recommendation and the actual application of CAM: 92% (n=71) of the patients with a CAM recommendation actually used CAM treatments while only 20% (n=13) of the patients without a CAM recommendation used CAM (p<0.0001). There was no association between the use of CAM and the source of CAM information (p=0.12) (Table 4).

|

Hopes relatedto CAM |

Frequency (n=82) |

% |

|

Cure |

79 |

96% |

|

Fighting cancer |

61 |

74% |

|

Preventionofmetastases |

43 |

52% |

|

Strengtheningofself-healing |

76 |

93% |

|

Quality oflife |

75 |

91% |

|

More energy/ vitality |

61 |

74% |

|

Improvedqualityoflife |

70 |

85% |

|

Mental stability |

43 |

52% |

|

Lesspain |

18 |

22% |

|

Strengthening of the immune system |

75 |

91% |

|

Support ofconventionaltreatment |

73 |

89% |

|

Alleviation of side effects of the conventional oncological treatment |

53 |

65% |

|

Replacementofconventionalmedicine |

2 |

2% |

Table 4: Hopes related to CAM treatments.

96% (n=79) of the CAM users were hoping that the use of CAM would cure the malignancy, placing special emphasis on the self-healing and a direct treatment of the malignancy. 91% (n=75) of the CAM users were looking for an improvement in the quality of life. CAM users were hopeful that CAM would potentiate the conventional oncological treatment (89%, n=73) and alleviate the side effects of the conventional therapy (65%, n=53). Only 2% (n=2) considered CAM as an alternative to the conventional oncological treatment.

The study evaluated the personal relevance of CAM versus conventional treatments to patients with gynecological malignancies. CAM treatments were considered as just as important as the conventional treatment by 56% (n=47) of the CAM users while 12% (n=10) considered them to be even more important. CAM treatments played a minor role in 32% (n=27) of all CAM users.

The monthly costs of the CAM treatments ranged between one and 50€ in 43% of the CAM users (n=34). 36% (n=29) spent over 100€ a month on CAM.

88% (n=123) of the gynecological cancer patients evaluated in this study would have liked to be treated by physicians with more knowledge on CAM. CAM users (98.8%, n=81) as well as non-CAM users desired a more extensive CAM training for physicians (91.3%, n=42). 90% (n=127) of the patients would support the complete integration of CAM into the health care system, representing 100% (n=83) of the CAM users and 91.7% (n=44) of the non-CAM users.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the use of CAM in gynecologic malignancies was assessed by offering 22 response options and one free-text category. 84 of the 141 patients who answered the questionnaire stated that they used CAM treatments, corresponding to a prevalence of CAM use of 60%. In the literature, the prevalence of the use of CAM in patients with gynecological malignancies has been reported to range between 39% and 76 [20,21].

A prevalence of 60% falls within the upper range of the range described in the literature for both oncological patients overall as well as patients with gynecological cancers. It needs to be taken into account that the relatively high prevalence of the use of CAM may be due to a selection bias since unlike most other hospitals, the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the Technical University Munich, Germany, offers a CAM clinic. It is therefore possible patients were made more aware of the option of CAM treatments.

This hypothesis is further supported by the assessment of the sources of information regarding CAM treatments: 61% of the patients included in this study reported to have received information on CAM from their physician. Based on the results of the study, a majority of the patients whose recommendation to use CAM was provided by physicians were given this recommendation by a member of the medical staff of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the Technical University Munich, Germany, or of the CAM clinic. In contrast, many other reports described that very little or no information about CAMI was provided by physicians [4,14,22,23].

The current study reports a significant association between age and the use of CAM. Those who used CAM were significantly younger compared to non-CAM users (59 ± 11.1 years versus 67 ± 10.8 years, p<0.01) which is consistent with the literature on the use of CAM in an oncological as well as the general patient population [4,16,21,24].

There was a consistent increase in the use of CAM with a higher level of education in the current study (primary school to high school level) in the current study, leading to a statistically significant association between the level of education and the use of CAM. This association is also consistent with the data reported in the literature [14,24-26]. According to Lengacher and Moschèn, the more frequent use of CAM with a higher level of education may be a result of a skepticism towards conventional medicine and a more profound knowledge about CAM treatments [26,27].

There was a significantly higher use of CAM in patients who underwent chemotherapy as part of their oncological treatment compared to patients who did not. The significant association between the use of CAM and chemotherapy has been described in several studies [11,24,28-30].

Frequent psychological as well as physical chemotherapy side effects such as stress, nausea and polyneuropathy and the desire to alleviate these symptoms by using CAM might explain this association [4,23]. Compared to non-CAM users, significantly more CAM users had a normal BMI (18.5-24.9). While there are no data on a potential link between the BMI and the use of CAM in patients with gynecological malignancies, a similar association has been described in a study of 3,411 breast cancer patients [31]. This “EvAluate” trial evaluated 3,411 postmenopausal breast cancer patients and reported a significantly higher interest in CAM in patients with a normal BMI (20-25 kg/m²) [13]. Patients with a normal BMI may be more conscious of their health than over- or underweight patients, and may prefer a holistic treatment approach [32].

In our study there was no significant correlation between a religious or spiritual faith and the use of CAM techniques, which is consistent with data on various tumor entities [28,30]. However, this interpretation is of limited value since there is no common definition of CAM in the literature. Specifically, prayers are often defined as CAM treatments in American publications which makes an association between religiosity and the use of “CAM” more likely [20].

The use of „trace elements“ (71%, e.g. zinc, selenium, L-carnitine) was the most frequent CAM therapy reported, followed by „vitamins“ (64%), “phytotherapeuty” (58%), “homeopathy” (55%) and “anthroposophical medicine” (64%). This is consistent with previous data by Drozdoff et al., and Schuerger et al., who evaluated breast and gynecological cancer patients at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Technical University Munich, Germany, and also concluded that phytotherapeutics, vitamins, trace elements and vitamins were the most frequently applied CAM methods [11,12]. However, there may be an overlap of the patients included in these and the current study since the prior studies also included breast and gynecological cancer patients from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Technical University Munich, Germany.

Because of the heterogenous definitions of CAM, an international comparison between CAM trials is very challenging. A Canadian publication evaluated the use of CAM in a gynecological oncological population and reported „prayers“, „diets“ and „physical therapy“ as the most frequently used CAM treatments (McKay et al., 2005). The current study considered none of the above methods as CAM treatments, making a comparison very difficult. Swisher et al. divided the types of CAM treatments into two categories (“ingestible” as well as “spiritual” treatments) within a patient population with gynecological malignancies and detected that patients most frequently used phytotherapy, vitamins and trace elements [23]. Molassiotis et al. evaluated the use of CAM in 956 patients diagnosed with various tumor entities all over Europe and reached similar results compared to the current study, quoting phytotherapy, homeopathy, vitamins, trace elements as well as healing teas as the most frequently used CAM treatments [4].

A recommendation to use CAM (95%), the desire to be actively involved in the treatment (87%), the holistic CAM approach (86%) as well the desire to exhaust all therapeutic options (81%) were reported as the major reasons for a use of CAM. In addition, patients associated hopes and expectations with CAM, specifically an increase in the efficiency of the conventional oncological treatment by activating self-healing powers (93%), strengthening the immune system (93%) as well as an overall support of the conventional oncological treatment (89%). Patients were also hoping for an overall improvement in the quality of life (85%), an increase in energy (74%) and an alleviation of the side effects of the conventional oncological treatment (65%). These results are comparable to the results in the literature that report the support of a potential cure and/ or of the immune system, a physical/ psychological strengthening and the desire to exhaust all therapeutic options as important motivators for the use of CAM in patients with gynecological malignancies [4,20,21,23,33].

Family members/ friends and the media have been reported as the most commonly used sources of information regarding CAM by patients with gynecological malignancies [4,14,20,23,33]. In the current study, information on CAM was most commonly derived from the medical literature (63%) and physicians (61%). 49% of the patients gathered information from the media (internet, television), only 26% from family members and friends. Other sources of information were fellow patients/ self-help groups (19%), professional organizations (19%) and naturopaths (9%). Unlike in prior studies stating family members/ friends and the media as the major sources of information, patients gathered information on CAM primarily from professional sources in the current study (medical literature, physicians). This may indicate that CAM methods are increasingly being considered as serious therapeutic options, and that patients are more inclined to rely on the professional opinion of their physicians in order to weigh the potential advantages of CAM against their limitations and possible interactions with conventional oncological treatments. The strong involvement of the treating physicians in particular is unlike previously reported results. 61% of the patients in this trial were informed on CAM therapies by their physicians while this information was triggered by physicians or other medical staff in only 7-22% of the patients in the literature [4,14,20,23].

46% of the patients reported having received a recommendation regarding the use of CAM in the current study. Physicians were stated as the most frequent sources of the recommendations (79%), followed by family members/ friends (28%) and naturopaths (16%). The source of the recommendation and the subsequent use of CAM has not been evaluated in patients with gynecological malignancies to date. The high rate of CAM recommendations by physicians is likely due to the presence of a CAM clinic at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Technical University Munich, Germany. 41% of the recommendations were made by the medical staff of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Technical University Munich, Germany, and 33% of the recommendations directly by the staff of the CAM clinic. Although the source of the CAM recommendation may not be representative for all patients with gynecological malignancies, it is noteworthy that patients were significantly more inclined to use CAM after a recommendation, regardless of the source of the recommendation. This is consistent with results of Mao et al. who evaluated 1,471 cancer survivors and detected an increased use of CAM after a clear recommendation for CAM [34]. This observation is of particular importance for physicians since patients may receive recommendations regarding alternative treatment methods from unprofessional sources and may subsequently be at risk to apply inefficient or even dangerous CAM methods. In order to avoid unnecessary risks and to protect the patients, recommendations for the use of CAM should be made by physicians or sufficiently trained medical staff only.

CONCLUSION

Our data demonstrate a high overall interest in CAM in patients with gynecological cancer. Health care professionals should be aware of this in order to be able to better address their patients´ needs. It is necessary to explore the use of CAM with cancer patients, to educate those regarding potentially beneficial and harmful therapies even in the light of the limited available evidence, and to work towards an integrated model of health-care.

DECLARATIONS

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The final version was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Technical University of Munich (TUM) with the project number 4/15. A preliminary statement before the beginning of the interview informed the patients about the voluntary and pseudonymous nature of the study as well as its purpose. Consent to participate in the study was obtained verbally as approved by the ethics committee. Respondents were not offered any incentive for study participation.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

FUNDING

The authors received no specific funding for this work

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

- • DP Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing review and editing

- • CW Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing- review and editing, Visualization

- • AH Formal analysis, Methodology

- • MK Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision

- • CB Writing- review and editing

All authors have read and approved to manuscript before publication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Not applicable

REFERENCES

- Berretta M, Pepa CD, Tralongo P, Fulvi A, Martellotta F, et al. (2017) Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) in cancer patients: an Italian multicenter survey. Oncotarget 8: 24401-24414.

- McFarland B, Bigelow D, Zani B, Newsom J, Kaplan M (2002) Complementary and alternative medicine use in Canada and the United States. Am J Public Health 92: 1616-1618.

- Xue CC, Zhang AL, Lin V, Da Costa C, Story DF (2007) Complementary and alternative medicine use in Australia: a national populationbased survey. J Altern Complement Med 13: 643-650.

- Molassiotis A, Fernandez-Ortega P, Pud D, Ozden G, Scott JA, et al. (2005) Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: a European survey. Ann Oncol 16: 655-663.

- Bahall M (2017) Prevalence, patterns, and perceived value of complementary and alternative medicine among cancer patients: a cross-sectional, descriptive study. BMC Complement Altern Med 17: 345.

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (2018) Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s In a Name? National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, USA.

- Greenlee H, Kwan ML, Ergas IJ, Sherman KJ, Krathwohl SE, et al. (2009) Complementary and alternative therapy use before and after breast cancer diagnosis: the Pathways Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 117: 653-665.

- Wanchai A, Armer JM, Stewart BR (2010) Complementary and alternative medicine use among women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Clin J Oncol Nurs 14: 45-55.

- Fasching PA, Thiel F, Nicolaisen-Murmann K, Rauh C, Engel J, et al. (2007) Association of complementary methods with quality of life and life satisfaction in patients with gynecologic and breast malignancies. Support Care Cancer 15: 1277-1284.

- Fremd C, Hack CC, Schneeweiss A, Rauch G, Wallwiener D, et al. (2017) Use of complementary and integrative medicine among German breast cancer patients: predictors and implications for patient care within the PRAEGNANT study network. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 295: 1239-1245.

- Drozdoff L, Klein E, Kiechle M, Paepke D (2018) Use of biologically-based complementary medicine in breast and gynecological cancerpatients during systemic therapy. BMC Complement Altern Med 18: 259.

- Schuerger N, Klein E, Hapfelmeier A, Kiechle M, Brambs C, et al. (2019) Evaluating the Demand for Integrative Medicine Practices in Breast and Gynecological Cancer Patients. Breast Care (Basel) 14: 35-40.

- Hack C, Fasching P, Fehm T, De Waal J, Rezai M, at al. (2017) Interest in Integrative Medicine Among Postmenopausal Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer Patients in the EvAluate-TM Study. Integr Cancer Ther 16: 165-175.

- Navo MA, Phan J, Vaughan C, Palmer JL, Michaud L, et al. (2004) An assessment of the utilization of complementary and alternative medication in women with gynaecologic or breast malignancies. J ClinOncol. 22: 671-677.

- Hammersen F, Pursche T, Fischer D, Katalinic A, Waldmann A (2020) Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among Young Patients with Breast Cancer. Breast Care 15: 163-170.

- Söllner W, Maislinger S, DeVries A, Steixner E, Rumpold G, et al. (2000) Use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients is not associated with perceived distress or poor compliance with standard treatment but with active coping behavior: a survey. Cancer 89: 873-880.

- Lopez G, McQuade J, Cohen L, Williams JT, Spelman AR, et al. (2017) Integrative Oncology Physician Consultations at a Comprehensive Cancer Center: Analysis of Demographic, Clinical and Patient Reported Outcomes. J Cancer 8: 395-402.

- Verhoef MJ, Balneaves LG, Boon HS, Vroegindewey A (2005) Reasons for and Characteristics Associated WithComplementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Integr Cancer Ther 4: 274-286.

- Gentry-Maharaj A, Karpinskyj C, Glazer C, Burnell M, Bailey K, et al. (2017) Prevalence and predictors of complementary and alternative medicine/non-pharmacological interventions use for menopausal symptoms within the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening. Climacteric 20: 240-247.

- McKay DJ, Bentley JR, Grimshaw RN (2005) Complementary and Alternative Medicine in GynaecologicOncology. J Obstet and Gynaecol Can 27: 562-568.

- Münstedt K, Kirsch K, Milch W, Sachsse S, Vahrson H (1996) Unconventional cancer therapy - Survey of patients with gynaecological malignancy. Arch GynecolObstet 258: 81-88.

- Paul M, Davey B, Senf B, Stoll C, Münstedt K, et al. (2013) Patients with advanced cancer and their usage of complementary and alternative medicine. J Cancer Res ClinOncol 139: 1515-1522.

- Swisher EM, Cohn DE, Goff BA, Parham J, Herzog TJ, et al. (2002) Use of complementary and alternative medicine among women with gynaecologic cancers. GynecolOncol 84: 363-367.

- Paltiel O, Avitzour M, Peretz T, Cherny N, Kaduri L, et al. (2001) Determinants of the Use of Complementary Therapies by Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol 19: 2439-2448.

- Astin JA (1998) Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. Jama 279: 1548-1553.

- Moschèn R, Kemmler G, Schweigkofler H, Holzner B, Dünser M, et al. (2001) Use of alternative / complementary therapy in breast cancer patients - a psychological perspective. Supportive Care Cancer 9: 267-274.

- Lengacher CA, Bennett MP, Kip KE, Keller R, Lavance MS, et al. (2002) Frequency of Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Women with Breast Oncol Nurs Forum 29: 1445-1452.

- Hyodo I, Amano N, Eguchi K, Narabayashi M, Imanishi J, et al. (2005) Nationwide survey on complementary and alternative medicine in cancerpatients in Japan. J Clin Oncol 23: 2645-2654.

- Richardson MA, Sanders T, Palmer JL, Greisinger A, Singletary SE (2000) Complementary/ Alternative Medicine Use in a Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Implications for Oncology. J ClinOncol 18: 2505-2514.

- Tas F, Ustuner Z, Can G, Eralp Y, Camlica H, et al. (2005) The prevalence and determinants of the use of complementary and alternative medicine in adult Turkish cancer patients. Acta Oncol 44: 161-167.

- Pedersen CG, Christensen S, Jensen AB, Zachariae R (2009) Prevalence, socio-demographic and clinical predictors of post-diagnostic utilisation of different types of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in a nationwide cohort of Danish women treated for primary breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 45: 3172-3181.

- McKenzie J, Keller HH (2010) Who are the users of vitamin-mineral and herbal preparations among community-living older adults? Canadian Journal on Aging 22: 167-175.

- Nazik E, Nazik H, Api M, Kale A, Aksu M (2012) Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use byGynecologicOncologyPatients in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 13: 21-25.

- Mao JJ, Palmer CS, Healy KE, Desai K, Amsterdam J (2011) Complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer survivors: a population-based study. J Cancer Surviv 5: 8-17.

Citation: Paepke D, Wiedeck C, Hapfelmeier A, Kiechle M, Brambs C (2020) Frequency and Predictors for the Use of Complementary Medicine among Gynecological Cancer Patients. J Altern Complement Integr Med 6: 133.

Copyright: © 2020 Paepke D#, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.