Advances in Microbiology Research Category: Microbiology

Type: Review Article

Gammaproteobacteria and Firmicutes are Resistant to Long-Term Chromium Exposure in Soil

*Corresponding Author(s):

Dorothea K ThompsonDepartment Of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Campbell University, Buies Creek, North Carolina, United States

Tel:+1 9108937463,

Email:dthompson@campbell.edu

Received Date: Dec 01, 2017

Accepted Date: Jan 06, 2018

Published Date: Jan 22, 2018

Abstract

The impact of long-term chromium contamination on the structure of soil microbial communities under relevant field conditions remains inadequately documented, despite the prevalent deposition of toxic chromate in both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems due to anthropogenic activities. In this study, Small-Subunit (SSU) ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene clone technology was employed to ascertain the effects of chronic Chromium (Cr) exposure on the diversity and structure of soil microbial communities. Our results demonstrated that soil contaminated with high Cr levels (769.9 ± 74.7 mg kg-1) was dominated by 16S rRNA gene phylotypes affiliated with the phyla of Proteobacteria (45%) and Firmicutes (30%), where as the control soil (10.5 ± 2.3 mg kg-1 Cr) exhibited a more even distribution of SSU rRNA gene clones across the phyla of Proteobacteria (20%), Bacteroidetes (25%), and Actinobacteria (20%). The phylogenetic data suggest an increase in Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, with a complete loss of different phyla of Thermomicrobiae, Acidobacteria, and Verrucomicrobiae in response to high levels of chromium. The contaminated soil community also was characterized by a substantial loss in 16S rRNA gene phylotypes closely related to members of the Beta and Delta classes of Proteobacteria. No members of the Gammaproteobacteria were present in the control soil in marked contrast to the highly Cr-contaminated soil, where Gammaproteobacteria comprised 30% of the derived clone library. A number of the contaminated soil clones had high sequence similarity (>98%) to Cr (VI)-reducing Pseudomonas spp. This research underscores the high metal resistance of Gammaproteobacteria constituents.

Keywords

Bacterial phylogenetics; Chromium stress; Small-subunit ribosomal RNA gene clone technology; Soil microbial communities

INTRODUCTION

Hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)], in the form of chromate (CrO42-) or dichromate (Cr2O72-), is a widely distributed anthropogenic pollutant in terrestrial ecosystems due to its prevalent use as a strong oxidizing agent in various industrial processes and military defense applications [1,2]. Environmental chromium (Cr) persists predominantly in one of two chemically stable oxidation states, the trivalent form [Cr(III)] or the hexavalent form [Cr(VI)] [3]. Oxyanion chromate is mobile in soils and sediments due to its high water solubility [3,4]. Moreover, Cr(VI) is highly toxic to all living organisms, with chronic exposures leading to such detrimental health impacts as mutagenesis and carcinogenesis [5-7]. The adverse biological effect of chromate is attributable to its transport across cellular membranes via surface anion transport systems [4,8,9]. Chromate toxicity is associated with the generation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) during the intracellular partial reduction of Cr(VI) to the unstable intermediate Cr(V), a highly reactive radical that can be spontaneously oxidized back to Cr(VI) during redox cycling [4,10,11]. Oxidative-induced DNA damage is considered to be the basis of chromate genotoxicity [12-14]. By contrast, the reduced form of chromium, Cr(III), is either water insoluble or sparingly soluble in the hydroxide and oxide forms [4] and much less toxic, being conventionally considered as a micronutrient in the human diet [15].

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) is faced with the complex challenge of managing, remediating, and monitoring hazardous mixed wastes present in the subsurface environments of numerous DOE facility sites. Chromium is a risk-driving contaminant found at a number of DOE waste sites. Microbial catalysis of metal reduction constitutes a promising and potentially cost-effective strategy for the in situ remediation of metal-contaminated subsurface environments [16,17]. However, the biotransformation of toxic metal contaminants in natural environments is an inherently complex process that depends on the structure and dynamics of the indigenous microbial community, the types and concentration levels of the contaminants present, and the specific geochemical conditions characterizing the site [18].

Here we describe the molecular phylogenetic comparison of microbial communities from two contrasting vadose zone soils obtained from the DOE Hanford site in Washington State. The primary objective of this investigation was to characterize the impact of long-term, high-level Cr contamination on soil bacterial abundance, diversity, and community structure in soils under relevant field conditions. Toward that end, Small-Subunit (SSU) rRNA gene cloning technology was used to establish a culture-independent census of the indigenous microbial community. To our knowledge this is the first report that describes the in situmicrobial community structure in two soil samples comparable in texture, pH, and amounts of multiple metal pollution, but contrasting with respect to total Cr concentrations. The results obtained from this study provide valuable insight into bacterial community shifts in response to Cr-induced selective pressure.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) is faced with the complex challenge of managing, remediating, and monitoring hazardous mixed wastes present in the subsurface environments of numerous DOE facility sites. Chromium is a risk-driving contaminant found at a number of DOE waste sites. Microbial catalysis of metal reduction constitutes a promising and potentially cost-effective strategy for the in situ remediation of metal-contaminated subsurface environments [16,17]. However, the biotransformation of toxic metal contaminants in natural environments is an inherently complex process that depends on the structure and dynamics of the indigenous microbial community, the types and concentration levels of the contaminants present, and the specific geochemical conditions characterizing the site [18].

Here we describe the molecular phylogenetic comparison of microbial communities from two contrasting vadose zone soils obtained from the DOE Hanford site in Washington State. The primary objective of this investigation was to characterize the impact of long-term, high-level Cr contamination on soil bacterial abundance, diversity, and community structure in soils under relevant field conditions. Toward that end, Small-Subunit (SSU) rRNA gene cloning technology was used to establish a culture-independent census of the indigenous microbial community. To our knowledge this is the first report that describes the in situmicrobial community structure in two soil samples comparable in texture, pH, and amounts of multiple metal pollution, but contrasting with respect to total Cr concentrations. The results obtained from this study provide valuable insight into bacterial community shifts in response to Cr-induced selective pressure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling site and soil collection

A total of six soil samples were collected from the DOE Hanford 100D site near the city of Richland in southeastern Washington State, USA. The 100D area is the site of nine deactivated plutonium production reactors. Historically, potassium dichromate was used as a strong oxidizing agent in the redox process to manipulate the valence state of plutonium during cleanup of cold war military munitions at the DOE Hanford Site. Three separate samples designated as contaminated originated from the bedding sand beneath a 91 cm (36) diameter pipeline, with the anthropogenic source of long-term chromate contamination arising from a smaller tributary pipe located closer to the ground surface. Three control soil samples were collected at a depth of one meter from the ground surface at a nearby site located next to an active excavation trench that lacked the chromate-contaminating source pipe. Both subsurface vadose samples consisted of desiccated, sandy soils characteristic of this arid region in southeastern Washington State. Individual soil samples were homogenized and shipped overnight on ice to Purdue University (West Lafayette, IN, USA) where they were aseptically transferred to sterile Whirl-Pak bags (Nasco, Modesto, CA), immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C pending analysis.

Toxic metal content of soil samples

Soil analysis of total toxic metal content was performed by SGS Alvey Laboratories, Inc, (Belleville, IL, USA). Three biological replicates of each soil sample were assayed to determine soil pH and the total concentration of the following heavy metals: Cr, Cd, Co, Fe, Pb, and Ni.

DNA extraction and SSU rRNA gene library construction

Community genomic DNA (cgDNA) was isolated from one gram of soil samples essentially as published previously [19]. The concentration and quality of the extracted cgDNA was determined photometrically using a Nano Drop® ND-1000 UV-vis spectrophotometer (Nano Drop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Small-Subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) genes were amplified from cgDNA using PCR. The cgDNA (0.1-50 ng) was used as the template in a reaction containing 1X PCR buffer (500 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 300 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3]), 0.05% NP-40, 250 μM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.4 µM each of forward and reverse primer, and 0.04 U of REDTaq DNA polymerase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) per µl of reaction. SSU rRNA genes were amplified with the 1492r reverse universal (5’-GGT TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3’) and either the 8f Bacteria-specific forward (5’-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3’) or 4fa Archaea-specific forward (5’-TCC GGT TGA TCC TGC CRG-3’) oligonucleotide primers. Three sets of amplification reactions were performed for cgDNA from each soil sample. Each reaction set contained either 5% acetamide, 1 mM betaine, or no denaturant. Five replicates of each condition were performed. Reactions were incubated in a Master cycler EP thermo cycler (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY, USA) for 5 min at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 42°C for 45 sec, and 72°C for 2 min, and finally for a single 5-min extension period at 72°C. PCR products from replicate reactions were pooled, purified with a QIA quick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and eluted in TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 1 mM EDTA). In order to maximize ligation efficiency, purified PCR products were incubated for 10 min at 72°C in a reaction mixture containing 50 µM dATP and 0.02 U of REDTaq polymerase per µl of reaction. A-tailed PCR products were cloned into TOPO TA PCR4 and transformed into One Shot MAX Efficiency Escherichia coli DH5α-T1R according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Blue/white selection was used to identify putative SSU rRNA-containing clones, and individual white colonies were grown in 96-well plates containing Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and 25 μg/ml of kanamycin.

Sequencing of SSU rRNA gene clones

Clones containing SSU rRNA genes were sequenced at the Purdue Genomic Center (West Lafayette, IN, USA). Plasmid DNA was extracted by alkaline lysis, and DNA sequencing reactions were carried out with the Big Dye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Bio systems, Foster City, CA, USA) using the 8f (5’-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3’), 515f (5’-GTG CCA GCM GCC GCG GTA A-3’), and 1492r (5’-GGT TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3’) oligonucleotide primers [20]. DNA sequencing reactions were resolved with Applied Bio systems 3730XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Bio systems, Foster, CA, USA).

Chimera detection and phylogenetic analysis

Assembled contigs were screened for chimeric sequences using chimera check [21], bellerophon [22], and pintail [23].Overlapping primer runs for each clone were assembled in xplorseq [24], and the resulting contigs were imported into ARB [25] for alignment and phylogenetic analysis. Sequences were aligned against their nearest neighbors using the “Integrated-aligners” function in ARB, visually inspected, and adjusted where necessary. Aligned sequences were added to the starting tree using the ARB_PARS tool [25]. Of approximately 1500 nucleotides of sequence obtained from each of the SSU rDNA clones, 1160 unambiguously aligned positions were used for subsequent phylogenetic analyses. Aligned SSU rRNA sequences were downloaded from the SILVA database [26] into ARB [25] and used to construct phylogenetic trees using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method [27] and RAXML-III [28], the maximum-likelihood [29] implementation in ARB. Bootstrap re-sampling [30] was performed 10,000 times in NJ.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Toxic metal characteristics of sampling sites

In this study, we analyzed the bacterial community structure and species richness in vadose zone soils sampled from two locations within the 100D area of the DOE Hanford Washington Closure facility. Three independent replicates for each soil type (control and contaminated) were characterized in terms of total concentrations of potentially toxic metals (Ni, Pb, Cr, Fe, Co and Cd). The pH of the contaminated soil sample was only slightly more alkaline (pH 9.0 in all three replicates) than the pH of the paired control sample (mean pH 8.8; min pH 8.6; max pH 8.9). Soil properties such as pH can have large effects on the solubility of toxic metals and thus, can exert substantial influence on the diversity and composition of natural microbial communities [31]. One study examining the effect of long-term nickel exposure on soil microbial communities determined that the mean 3.5-unit difference in soil site pH largely accounted for the variation observed in bacterial 16S rRNA gene abundance and diversity [32]. The 0.2-unit variation between the pH of the control and contaminated samples in this study suggests that soil pH was likely not a major factor contributing to the observed differences in bacterial community compositions.

As shown in table 1, the soils extracted from the two sampling sites differed primarily in the amount of Cr. The total chromium concentrations in the control and contaminated soils were determined to be 10.5 ± 2.3 mg kg-1 and 769.9 ± 74.7 mg kg-1, respectively, which constituted a 70-fold difference. Both soil types also contained measurable amounts of Ni, Pb, Fe and Co, but the total concentrations of these toxic metals varied no more than 2.2-fold between the control and contaminated soils (Table 1). The total levels of Fe were particularly high in the 100D samples, attaining levels of 33,988 ± 1089.8 mg kg-1 in the control samples and 25,404 ± 265.2 mg kg-1 in the contaminated samples (Table 1). However, the variance in total Fe concentrations between the control and contaminated soil samples was only approximately 1.3-fold. Contaminated soils, therefore, differed primarily from control samples in terms of total chromium amounts, while the levels of Ni, Pb, Fe and Co were comparable between the two samples.

As shown in table 1, the soils extracted from the two sampling sites differed primarily in the amount of Cr. The total chromium concentrations in the control and contaminated soils were determined to be 10.5 ± 2.3 mg kg-1 and 769.9 ± 74.7 mg kg-1, respectively, which constituted a 70-fold difference. Both soil types also contained measurable amounts of Ni, Pb, Fe and Co, but the total concentrations of these toxic metals varied no more than 2.2-fold between the control and contaminated soils (Table 1). The total levels of Fe were particularly high in the 100D samples, attaining levels of 33,988 ± 1089.8 mg kg-1 in the control samples and 25,404 ± 265.2 mg kg-1 in the contaminated samples (Table 1). However, the variance in total Fe concentrations between the control and contaminated soil samples was only approximately 1.3-fold. Contaminated soils, therefore, differed primarily from control samples in terms of total chromium amounts, while the levels of Ni, Pb, Fe and Co were comparable between the two samples.

Community diversity and species richness

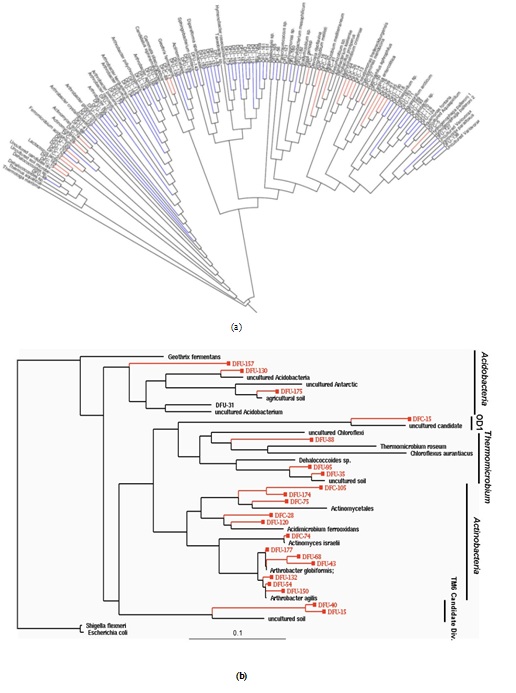

For both the control and contaminated soils, all Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) were assigned to Bacteria (Figures 1A and 1B), while no detectable PCR products were obtained from the community gDNA using the Archaea-specific SSU rRNA gene primers. Although the microbial communities in the control and contaminated soils comprised a wide range of different representatives within the bacterial domain, the overall microbial diversity and species richness were relatively limited at both sampling sites, with only five to six different phyla of Bacteria represented in the 16S rRNA gene clone libraries of the respective sites. Furthermore, for both the control and contaminated soils, the number of distinct phylotypes in each phylum division was small. With respect to the contaminated soil, a possible explanation for this limited number of distinct phylotypes is ostensibly the effect of long-term exposure of high chromium levels on the bacterial community structure in combination with the semi-arid, oligotrophic nature of the soil samples.

Figure 1: (a) Phylogeny of 146 OTUs recovered from control and contaminated soil 16S rRNA gene clone libraries.(A) This neighbor-join in gradial phylogenetic tree shows the relationships between DFU (control) and DFC (contaminated) clone library sequences from the 100D area of the DOE Hanford Site and their closely related sequences from the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP-II [21]). The branch colors are as follows: Bacteria, black; blue, DFU; red, DFC. (b) Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree depicting unique OTUs obtained within different bacterial phyla recovered from the DOE Hanford 100D site. The tree was constructed based on nearly complete SSU rRNA gene sequences retrieved from clone libraries of the control soil (DFU clones) and contaminated soil with high chromium levels (DFC clones). Escherichia coliM and Shigella flexneri 16S rDNA were the forced out groups. The scale at the bottom indicates sequence divergence.

Comparison of bacterial phylotype distributions

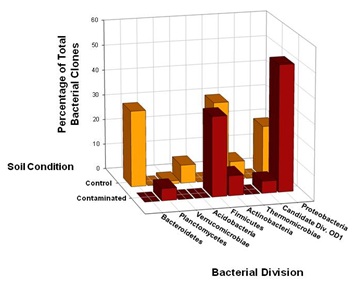

As depicted in figure 2, a general comparison of 16S rRNA gene phylotype distributions revealed that a very limited amount of divisional overlap existed among the bacterial community structures constituting the control and contaminated samples, except in the major bacterial lineages of Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria, where some overlap between the communities in the samples was observed. However, even in the division Actinobacteria, where there was a mixture of DFC (contaminated) and DFU (control) phylotypes, we never found the same phylotype representing both the DFC and DFU. The closest relationship observed was between clones DFC-105 and DFU-174, which had a sequence similarity of 93.5%, but this similarity was substantially below the 98% similarity cutoff established to define species-level OTUs. Sequence analysis of the clone libraries indicated that the contaminated and control soil samples did not contain a single phylotype in common, suggesting very little overlap in terms of species composition between the two microbial communities.

Members of the Proteobacteria (45%) and Firmicutes (30%) dominated the highly Cr-contaminated bacterial community (Figure 2). The phylogeny of the bacterial community reconstructed from the control samples, however, exhibited a more even distribution of clones across the most abundant phyla present: Proteobacteria (20%), Bacteroidetes (25%), and Actinobacteria (20%) (Figure 2). In 100D soils contaminated with high Cr levels, Proteobacteria were more abundant compared to the control, and the candidate OD1 division contained only DFC phylotypes (Figure 1B). However, the DFU (control) sample had a substantially higher percentage of Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Thermomicrobiae, and Verrucomicrobia than the DFC (contaminated) sample. The bacterial community structure shifted to decreased relative abundances of Thermomicrobiae, Actinobacteria, Acidobacteria, and Bacteroidetes in the presence of elevated chromium levels. By contrast, a high chromium concentration appeared to selectively favor Proteobacteria and Firmicutes. A similar dominance shift from Actinobacteria and Acidobacteria to Proteobacteria was observed for microbial communities in soils contaminated with chromium and arsenic [33]. Interestingly, 25% of the clones from the control soil were closely related to Arthrobacter spp., which are known for their high chromate resistance, while no close relatives of Arthrobacter spp. were identified in the contaminated sample (Figure 1B).

Members of the Proteobacteria (45%) and Firmicutes (30%) dominated the highly Cr-contaminated bacterial community (Figure 2). The phylogeny of the bacterial community reconstructed from the control samples, however, exhibited a more even distribution of clones across the most abundant phyla present: Proteobacteria (20%), Bacteroidetes (25%), and Actinobacteria (20%) (Figure 2). In 100D soils contaminated with high Cr levels, Proteobacteria were more abundant compared to the control, and the candidate OD1 division contained only DFC phylotypes (Figure 1B). However, the DFU (control) sample had a substantially higher percentage of Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Thermomicrobiae, and Verrucomicrobia than the DFC (contaminated) sample. The bacterial community structure shifted to decreased relative abundances of Thermomicrobiae, Actinobacteria, Acidobacteria, and Bacteroidetes in the presence of elevated chromium levels. By contrast, a high chromium concentration appeared to selectively favor Proteobacteria and Firmicutes. A similar dominance shift from Actinobacteria and Acidobacteria to Proteobacteria was observed for microbial communities in soils contaminated with chromium and arsenic [33]. Interestingly, 25% of the clones from the control soil were closely related to Arthrobacter spp., which are known for their high chromate resistance, while no close relatives of Arthrobacter spp. were identified in the contaminated sample (Figure 1B).

Figure 2: Comparison of bacterial 16S rRNA gene phylotype distributions in Hanford 100D soil samples at the phylum level. SSU rRNA genes were selectively amplified using PCR from community genomic DNA (cgDNA) that had been extracted from the contaminated and control soil samples. Clone libraries were constructed, and individual clones were sequenced and phylogenetically compared to cultivated organisms to establish a culture-independent census of the microbial community. The 63 unique DFC (contaminated) 16SrDNA clones and 83 unique DFU (control) 16S rDNA clones recovered from the soil samples were compared in terms of phylotype distributions at the taxonomic level of phylum.

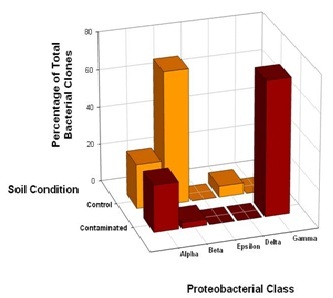

Further analysis of the distribution of DFU and DFC clones across classes within the phylum Proteobacteria revealed some striking features. Within the Proteobacteria, bacterial community overlaps were observed for the Alpha (α) and Beta (β) classes (Figure 3). Although 16S rRNA gene phylotypes assigned to Alphaproteobacteria were evenly distributed across the control and contaminated bacterial communities, 71% of the DFU clones derived from the control soil were closely related to Betaproteobacteria compared to 2% of the DFC clones, suggesting that these bacteria as a group are much less resistant to high chromium concentrations. The bacterial community structure appeared to shift from a dominance of Betaproteobacteria to a dominance of Gammaproteobacteria, presumably in response to chromium-induced selective pressure. Unexpectedly, there was a complete absence of Gammaproteobacteria in the control soil sample, where as Gammaproteobacteria comprised a total representation of 30% in the clone library derived from the contaminated soil sample (Figure 3). Representatives of the Epsilon (ε) class of Proteobacteria were not recovered from either the control or contaminated soils, where as a single DFU clone affiliated with the Delta (δ) class of Proteobacteria was recovered from the control soil (Figure 3).

Further analysis of the distribution of DFU and DFC clones across classes within the phylum Proteobacteria revealed some striking features. Within the Proteobacteria, bacterial community overlaps were observed for the Alpha (α) and Beta (β) classes (Figure 3). Although 16S rRNA gene phylotypes assigned to Alphaproteobacteria were evenly distributed across the control and contaminated bacterial communities, 71% of the DFU clones derived from the control soil were closely related to Betaproteobacteria compared to 2% of the DFC clones, suggesting that these bacteria as a group are much less resistant to high chromium concentrations. The bacterial community structure appeared to shift from a dominance of Betaproteobacteria to a dominance of Gammaproteobacteria, presumably in response to chromium-induced selective pressure. Unexpectedly, there was a complete absence of Gammaproteobacteria in the control soil sample, where as Gammaproteobacteria comprised a total representation of 30% in the clone library derived from the contaminated soil sample (Figure 3). Representatives of the Epsilon (ε) class of Proteobacteria were not recovered from either the control or contaminated soils, where as a single DFU clone affiliated with the Delta (δ) class of Proteobacteria was recovered from the control soil (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Comparison of bacterial community structure in Hanford 100D soil samples at the class level within the phylum Proteobacteria. The distribution of 32 unique DFC (contaminated) 16S rDNA clones and 18 unique DFU (control) 16S rDNA clones with affiliations to representatives within the phylum Proteobacteria was further analyzed in terms of Alpha, Beta, Delta, Epsilon and Gamma classes.

Prevalence of Pseudomonas spp. in Cr-contaminated soil

Chromium-selected dominant OTUs principally resided in the Gammaproteobacteria. Further phylogenetic analysis of the clone library derived from the contaminated soil sample indicated that seven 16S rRNA gene clones (DFC-7, DFC-13, DFC-27, DFC-53, DFC-70, DFC-71, and DFC-72) shared common lineages with cultured representatives in the bacterial family Pseudomonaceae. Seven DFC clones most closely related to Pseudomonas representatives constituted two distinct phylotypes: Phylotype I, which comprised DFC clones 7 and 13, and Phylotype II, which comprised DFC clones 27, 53, 70, 71, and 72. Phylotype I was most similar to the 16S rRNA gene sequence of Pseudomonas frederiksbergensis, and the two clones constituting Phylotype I had a pair wise sequence similarity of 99.8%. Although much remains to be elucidated about the metabolic capabilities of P.frederiksbergensis, this psychrotrophic bacterium can efficiently degrade aromatic hydrocarbons, including toluene and ethyl benzene, under aerobic conditions [34]. Phylogenetic analysis also demonstrated that Phylotype I had a high degree of sequence similarity (about 99.6%) to the 16S rRNA gene sequence of Pseudomonas fluorescens. P. fluorescens strain LB300 was isolated from chromium-contaminated river sediments and shown to exhibit plasmid-specified chromate resistance [35].

The DFC clones comprising Phylotype II were most closely related to Pseudomonas mendocina and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes, with pair wise similarities of greater than 99.5%. In previous work using soil artificially contaminated with 1000 mg Cr(VI) kg-1, resistant bacteria isolates were identified as members of [36]. These isolates were not only resistant to 40 mM Cr(VI) in pure culture, but showed high chromate reduction activity that was growth-phase dependent [36]. For other strains of P. mendocina, studies demonstrated that biotransformation of hexavalent chromium to its trivalent form was plasmid-mediated [37] and catalyzed by a periplasmic chromate reductase [38]. Additionally, an isolate belonging to P. pseudoalcaligenes based on 16S rDNA sequence similarity exhibited resistance to multiple toxic metals, including chromium [39].

The findings from this research are noteworthy because a number of Pseudomonas spp. have the capacity to mediate the complete bio reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III), including Pseudomonas putida [40-42], Pseudomonas sp. G1DM21 [43], Pseudomonas ambigua [44], Pseudomonas gessardii strain LZ-E [45], and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PCN-2 [46]. Collectively, the genus Pseudomonas is remarkable for its high degree of metabolic versatility, including hydrocarbon degradation and resistance to various toxic metals [47]. Presumably, the dominance of the genus Pseudomonas with in the soil bacterial communities subjected to high chromium stress in this study is due to their diverse functional capacity to resist and reduce high Cr (VI) concentrations. The high Cr(VI) resistance of Pseudomonas spp., together with their Cr(VI) reduction capability, indicate the potential utility of this genus as a bio augmentation organism for remediation of complex contaminated soils, such as those present at U.S. Department of Energy sites. The development of effective remediation strategies will require knowledge of the effects of long-term chromium exposure on resident microbial communities.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated a substantial shift in community dominance from Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes in control soils to Firmicutes and Proteobacteria in chromium-contaminated soils. Further analysis showed that Gammaproteobacteria dominated contaminated soils, while Betaproteobacteria dominated the control sample. These shifts in phylum level and proteobacterial class were dependent on differences in the chromium content of the soil samples, suggesting that Gammaproteobacteria exhibit some of the highest level of resistance to toxic metals at metal-contaminated sites.

The DFC clones comprising Phylotype II were most closely related to Pseudomonas mendocina and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes, with pair wise similarities of greater than 99.5%. In previous work using soil artificially contaminated with 1000 mg Cr(VI) kg-1, resistant bacteria isolates were identified as members of [36]. These isolates were not only resistant to 40 mM Cr(VI) in pure culture, but showed high chromate reduction activity that was growth-phase dependent [36]. For other strains of P. mendocina, studies demonstrated that biotransformation of hexavalent chromium to its trivalent form was plasmid-mediated [37] and catalyzed by a periplasmic chromate reductase [38]. Additionally, an isolate belonging to P. pseudoalcaligenes based on 16S rDNA sequence similarity exhibited resistance to multiple toxic metals, including chromium [39].

The findings from this research are noteworthy because a number of Pseudomonas spp. have the capacity to mediate the complete bio reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III), including Pseudomonas putida [40-42], Pseudomonas sp. G1DM21 [43], Pseudomonas ambigua [44], Pseudomonas gessardii strain LZ-E [45], and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PCN-2 [46]. Collectively, the genus Pseudomonas is remarkable for its high degree of metabolic versatility, including hydrocarbon degradation and resistance to various toxic metals [47]. Presumably, the dominance of the genus Pseudomonas with in the soil bacterial communities subjected to high chromium stress in this study is due to their diverse functional capacity to resist and reduce high Cr (VI) concentrations. The high Cr(VI) resistance of Pseudomonas spp., together with their Cr(VI) reduction capability, indicate the potential utility of this genus as a bio augmentation organism for remediation of complex contaminated soils, such as those present at U.S. Department of Energy sites. The development of effective remediation strategies will require knowledge of the effects of long-term chromium exposure on resident microbial communities.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated a substantial shift in community dominance from Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes in control soils to Firmicutes and Proteobacteria in chromium-contaminated soils. Further analysis showed that Gammaproteobacteria dominated contaminated soils, while Betaproteobacteria dominated the control sample. These shifts in phylum level and proteobacterial class were dependent on differences in the chromium content of the soil samples, suggesting that Gammaproteobacteria exhibit some of the highest level of resistance to toxic metals at metal-contaminated sites.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Financial support for the present study was provided by the Office of Science (BER), U.S. Department of Energy, and Environmental Remediation Sciences Program Grant No. DE-FG02-07ER64391. We are grateful to Drs. Jeff Serne and Evan Dresel of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) for generously supplying the soil samples used in this research. We thank Andrea T. McCarthy for excellent technical assistance. Finally, we thank Allison Witt and Phillip San Miguel of the Purdue University Genomics Center for high-throughput sequencing and for providing a description of the DNA sequencing procedure for this manuscript.

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:

Authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this research.

REFERENCES

- Langard S (1980) Chromium. Academy Press Inc, New York, USA.

- James BR (1996) Peer reviewed: the challenge of remediating chromium-contaminated soil. Environ Sci Technol 30: 248-251.

- Kamaludeen SP, Megharaj M, Juhasz AL, Sethunathan N, Naidu R (2003) Chromium-microorganism interactions in soils: remediation implications. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 178: 93-164.

- Cervantes C, Campos García J, Devars S, Gutiérrez Corona F, Loza Tavera H, et al. (2001) Interactions of chromium with microorganisms and plants. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 25: 335-347.

- Katz SA, Salem H (1993) The toxicology of chromium with respect to its chemical speciation: a review. J Appl Toxicol 13: 217-224.

- Klein C, Snow E, Frenkel K (1998) Molecular mechanisms in metal carcinogenesis: Role of oxidative stress. Academic Press, New York, USA.

- Singh J, Carlisle DL, Pritchard DE, Patierno SR (1998) Chromium-induced genotoxicity and apoptosis: relationship to chromium carcinogenesis. Oncol Rep 5: 1307-1318.

- Ohtake H, Cervantes C, Silver S (1987) Decreased chromate uptake in Pseudomonas fluorescens carrying a chromate resistance plasmid. J Bacteriol 169: 3853-3856.

- Nies A, Nies DH, Silver S (1989) Cloning and expression of plasmid genes encoding resistances to chromate and cobalt in Alcaligenes eutrophus. J Bacteriol 171: 5065-5070.

- Suzuki T, Miyata N, Horitsu H, Kawai K, Takamizawa K, et al. (1992) NAD(P)H-dependent chromium (VI) reductase of Pseudomonas ambigua G-1: A Cr(VI) intermediate is formed during the reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III). J Bacteriol 174: 5340-5345.

- Liu S, Dixon K (1996) Induction of mutagenic DNA damage by chromium (VI) and glutathione. Environ Mol Mutagen 28: 71-79.

- Aiyar J, Berkovits HJ, Floyd RA, Wetterhahn KE (1990) Reaction of chromium (VI) with hydrogen peroxide in the presence of glutathione: reactive intermediates and resulting DNA damage. Chem Res Toxicol 3: 595-603.

- Luo H, Lu Y, Shi X, Mao Y, Dalal NS (1996) Chromium (IV)-mediated fenton-like reaction causes DNA damage: implication to genotoxicity of chromate. Ann Clin Lab Sci 26: 185-191.

- Viti C, Marchi E, Decorosi F, Giovannetti L (2014) Molecular mechanisms of Cr(VI) resistance in bacteria and fungi. FEMS Microbiol Rev 38: 633-659.

- Mertz W (1993) Chromium in human nutrition: a review. J Nutr 123: 626-633.

- Lovley DR, Coates JD (1997) Bioremediation of metal contamination. Curr Opin Biotechnol 8: 285-289.

- Gadd GM (2000) Bioremedial potential of microbial mechanisms of metal mobilization and immobilization. Curr Opin Biotechnol 11: 271-279.

- Atlas RM (1981) Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons: an environmental perspective. Microbiol Rev 45: 180-209.

- Dojka MA, Hugenholtz P, Haack SK, Pace NR (1998) Microbial diversity in a hydrocarbon- and chlorinated-solvent-contaminated aquifer undergoing intrinsic bioremediation. Appl Environ Microbiol 64: 3869-3877.

- Reysenbach AL, Giver LJ, Wickham GS, Pace NR (1992) Differential amplification of rRNA genes by polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol 58: 3417-3418.

- Cole JR, Chai B, Farris RJ, Wang Q, Kulam-Syed-Mohideen AS, et al. (2007) The ribosomal database project (RDP-II): introducing myRDP space and quality controlled public data. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 169-172.

- Huber T, Faulkner G, Hugenholtz P (2004) Bellerophon: a program to detect chimeric sequences in multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 20: 2317-2319.

- Ashelford KE, Chuzhanova NA, Fry JC, Jones AJ, Weightman AJ (2005) At least 1 in 20 16S rRNA sequence records currently held in public repositories is estimated to contain substantial anomalies. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 7724-7736.

- Frank DN (2008) XplorSeq: a software environment for integrated management and phylogenetic analysis of metagenomic sequence data. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 420.

- Ludwig W, Strunk O, Westram R, Richter L, Meier H, et al. (2004) ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1363-1371.

- Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K, Fuchs BM, Ludwig W, et al. (2007) SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 7188-7196.

- Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4: 406-425.

- Stamatakis A, Ludwig T, Meier H (2005) RAxML-III: a fast program for maximum likelihood-based inference of large phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 21: 456-463.

- Felsenstein J (1981) Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. J Mol Evol 17: 368-376.

- Felsenstein J (1985) Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783-791.

- Giller KE, Witter E, McGrath SP (1998) Toxicity of heavy metals to microorganisms and microbial processes in agricultural soils: A review. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 30: 1389-1414.

- Li J, Hu HW, Ma YB, Wang JT, Liu YR, et al. (2015) Long-term nickel exposure altered the bacterial community composition but not diversity in two contrasting agricultural soils. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 22: 10496-10505.

- Sheik CS, Mitchell TW, Rizvi FZ, Rehman Y, Faisal M, et al. (2012) Exposure of soil microbial communities to chromium and arsenic alters their diversity and structure. PLoS One 7: 40059.

- Abdel-Megeed A, Mueller R (2009) Degradation of long chain alkanes by a newly isolated Pseudomonas frederiksbergensis at low temperature. Bioremediat Biodivers Bioavailab 3: 55-60.

- Bopp LH, Chakrabarty AM, Ehrlich HL (1983) Chromate resistance plasmid in Pseudomonas fluorescens. J Bacteriol 155: 1105-1109.

- Viti C, Decorosi F, Tatti E, Giovannetti L (2007) Characterization of chromate-resistant and –reducing bacteria by traditional means and by a high-throughput phenomic technique for bioremediation purposes. Biotechnol Prog 23: 553-559.

- Dhakephalkar PK, Bhide JV, Paknikar KM (1996) Plasmid mediated chromate resistance and reduction in Pseudomonas mendocina MCM B-180. Biotechnology Letters 18: 1119-1122.

- Rajwade JM, Salunkhe PB, Paknikar KM (1999) Biochemical basis of chromate reduction by Pseudomonas mendocina. Process Metallurgy 9: 105-114.

- Kumar V, Singh S, Singh J, Upadhyay N (2015) Potential of plant growth promoting traits by bacteria isolated from heavy metal contaminated soils. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 94: 807-814.

- Ishibashi Y, Cervantes C, Silver S (1990) Chromium reduction in Pseudomonas putida. Appl Environ Microbiol 56: 2268-2270.

- Park CH, Keyhan M, Wielinga B, Fendorf S, Matin A (2000) Purification to homogeneity and characterization of a novel Pseudomonas putida chromate reductase. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 1788-1795.

- Priester JH, Olson SG, Webb SM, Neu MP, Hersman LE, et al.(2006) Enhanced exopolymer production and chromium stabilization in Pseudomonas putida unsaturated biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 1988-1996.

- Desai C, Jain K, Madamwar D (2008) Hexavalent chromate reductase activity in cytosolic of Pseudomonas sp. G1DM21 isolated from Cr(VI) contaminated industrial landfill. Process Biochemistry 43: 713-721.

- Horitsu H, Futo S, Miyazawa S, Ogai S, Kawai K (1987) Enzymatic reduction of hexavalent chromium by hexavalent chromium tolerant Pseudomonas ambigua G-1. Agric Biol Chem 51: 2417-2420.

- Huang H, Wu K, Khan A, Jiang Y, Ling Z, et al. (2016) A novel Pseudomonas gessardii strain LZ-E simultaneously degrades naphthalene and reduces hexavalent chromium. Bioresour Technol 207: 370-378.

- He D, Zheng M, Ma T, Li C, Ni J (2015) Interaction of Cr(VI) reduction and denitrification by strain Pseudomonas aeruginosa PCN-2 under aerobic conditions. Bioresour Technol 185: 346-352.

- Timmis KN (2002) Pseudomonas putida: a cosmopolitan opportunist par excellence. Environ Microbiol 4: 779-781.

Citation: Thompson DK, Wickham GS (2018) Gammaproteobacteria and Firmicutes are Resistant to Long-Term Chromium Exposure in Soil. Adv Microb Res 2: 002.

Copyright: © 2018 Dorothea K Thompson, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Journal Highlights

© 2026, Copyrights Herald Scholarly Open Access. All Rights Reserved!