Health Professions Students’ Knowledge of and Attitude toward Complementary and Alternative Medicine

*Corresponding Author(s):

Peter R ReuterMarieb College Of Health And Human Services, Florida Gulf Coast University, Fort Myers, Florida, United States

Tel:+12395907512,

Email:preuter@fgcu.edu

Abstract

The aim of our study was to explore the knowledge of and attitude toward Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) among health professions students. Overall 763 undergraduate health professions students at a university in the United States completed online surveys asking questions concerning their experience with, attitude toward, and knowledge of CAM in general as well as specific CAM practices. They also provided information on which CAM practices they intend to incorporate into their future career.

Respondents reported an overall positive attitude toward and interest in CAM. Ninety percent had heard of and three-quarters reported previous experience with CAM practices. Respondents alluded to personal experience but also to knowledge gained about CAM in classes and clinical assignments. Acupuncture, yoga, massage therapy, meditation, cupping, aromatherapy, and chiropractic care were the CAM practices most respondents had heard about; yoga, meditation, massage therapy, aromatherapy, and chiropractic care were the CAM practices most respondents reported personal experience with. The top five practices students planned on making part of their career were yoga, meditation, massage therapy, diet-based therapy, and music therapy. Graduating health professions students had a more positive attitude toward CAM than pre-health professions students. They also had a higher average score for their interest in learning about CAM practices. Three-quarters of respondents planned on making CAM part of their career.

Keywords

CAM; Complementary and Alternative Medicine; Health professions; Health professions students; Pre-health professions students

Introduction

According to the 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), four out of ten American adults use health care practices that are not typically part of conventional medical care or that may have origins outside of usual Western healthcare norms [1]. Such practices are considered “complementary” if used together with conventional medicine and “alternative” if used instead of conventional medicine [2]. Therefore, the term Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) encompasses a wide variety of therapies and systems. The popularity of certain CAM therapies in certain countries or ethnic populations can be attributed to cultural factors such as religion [3]. Some CAM practices, such as meditation and yoga, are popular due to the fact that there are no negative side effects [4]. The 2012 NHIS suggested that CAM users in the United States were more likely to use complementary therapies for overall wellness rather than for medical treatment [1].

Health professionals play important roles in helping patients use CAM practices safely and accurately. For example, Stussman et al., (2020) reported that 53% of doctors in the U.S. had recommended at least one CAM practice to patients during the previous 12 months [5]. More than 80% of nurse practitioners recommended CAM treatments to patients in a study by Sohn and Loveland Cook (2002) and a systematic review by Hall et al., (2017) found that nurses promote CAM therapies to their patients [6,7]. Many healthcare providers have added CAM practice facilities, such as the Duke Center for Integrative Medicine and the Arizona Center for Integrative Medicine. Consequently, it is important for future health professionals to learn about CAM practices during their time in undergraduate and graduate programs. To satisfy this need for education, teaching CAM in nursing and medical schools, and other health professions programs is becoming more prevalent.

On the other hand, since most CAM practices are rooted in defined cultural settings, and because of lingering doubts about their efficacy and lack of scientific evidence, these educational efforts may not succeed if students have a negative attitude toward CAM [8,9]. Over the last two decades, a number of studies involving medical and pharmacy students from different countries have been published [10-14]. They all reported that most students had positive attitudes towards CAM, were interested in training in CAM practices, and were open to using or recommending CAM methods to their patients in their future professional lives. Studies on the use of, attitude toward, and knowledge of CAM in general student populations or health professional students from around the world paint a picture of great diversity shaped by cultural and societal factors [3,15-17]. For example, a study surveying university students in Atlanta (USA), New Delhi (India), and Newcastle upon Tyne (UK) found that the use of whole medical systems, such as ayurveda and homeopathy, was more prevalent among the students in New Dehli [3].

The current study is the first to look specifically at the knowledge of and attitude toward CAM of undergraduate health professions students at a university in the United States. A study by Zimmerman and Kandiah (2012) focused on students' perceptions of, familiarity with, and knowledge of herbal supplements [18]. Liu et al., (2014) conducted a cross-sectional electronic survey study among undergraduate students at the University of California (UC) Irvine; forty-four percent of participants described themselves as studying for a healthcare-related profession [19]. The same percentage of students described themselves as being in a healthcare-related major in a study by Mhatre, Artani and Sansgiry (2011) at the University of Houston [20]. The studies by Nguyen et al., and Johnson & Blanchard investigated the use of and interest in CAM among undergraduate (Johnson & Blanchard) and both graduate and undergraduate students (Nguyen et al.,) [21,22].

Methods

Ethical research statement

The research protocol was approved by an ethical review board (Institutional Review Board). Data collection followed all laws relevant to the survey of university student populations and all members of the research team completed training in ethical data collection through the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI).Participation was voluntary and students did not receive any benefits for responding.

Data collection

Students were invited to participate in one of two anonymous online surveys depending on whether they were pre-health professions students or graduating health professions seniors. The first survey was aimed at students taking Anatomy & Physiology with lab I and II courses, which are prerequisites for admission to upper level programs such as nursing at our university. The second survey was a modified version with additional questions to acquire more information from graduating seniors in health professions programs.

CAM practices can be subdivided into five groups: (1) alternative medical systems, (2) mind-body interventions, (3) biologically based treatment, (4) manipulation and body-based treatment, and (5) energy therapies [7]. The surveys listed CAM practices that covered all five groups.

Data analyses

Data are presented as percentage of the total participant pool, or a portion of this pool, for questions with categorical answers. For questions with quantitative answers, data are generally presented as means with standard deviations. Due to the voluntary nature of the survey, sample sizes vary for different analyses but are indicated. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP software program Version 14 (JMP®; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).Non-parametric Wilcoxon Rank Sums Tests were used to examine where attitudes toward and interest in CAM differed between pre-health and health professions students.

Results

Study population

The two online surveys were completed by 766 students overall. However, three responses were excluded because respondents indicated being younger than 18 years of age. Of the 763 study responses analyzed, 547 responses (71.7%) were from pre-health professions students and 216 responses (28.3%) came from graduating health professions seniors. Pre-nursing students made up the bulk of the pre-health professions students (47.9%), followed by Health Sciences (15.9%), Exercise Science (14.4%), Public Health (8.0%), Biology (3.7%), and Psychology (2.7%) majors. Among graduating seniors, 85% of respondents were Health Science (34.7%), Nursing (25.0%), Community Health (13.4%) or Exercise Science (11.6%) students.

|

Study population profile Biological sex: 83.2% female students, 16.4% male students, 0.2% no information Race/ethnicity: 65.4% Caucasian/White, 14.9% Hispanic, 6.3% African-American/Black, 1.4% East Asian, 11.8% more than one ethnicity/race or ethnicity/race other than listed, 0.2% no information Age: 20.76 ± 3.6 years (mean ± standard deviation; range: 18 - 51 years; median age = 20 years) Student population: 25.6% freshman, 28.6% sophomore, 8.7% junior, 30.8% senior, 2.4% second degree-seeking, non-degree seeking, and graduate students, 4.1% no information provided |

Attitude toward and interest in CAM in general

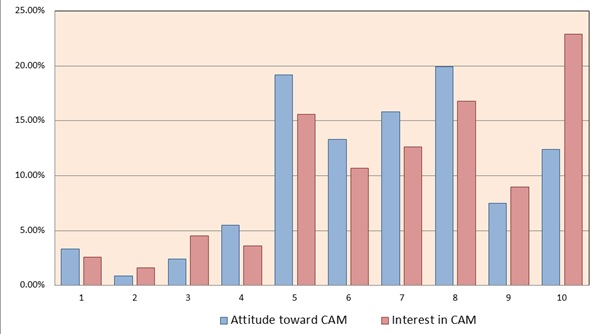

The overall attitude toward CAM of responding students was positive with 39.8% of respondents rating their attitude as ≥8 on a scale of 1-10 (1 = I just don’t care for it; 5-6 I think it’s okay; 10 = I love it); the average rating was 6.7 with a standard deviation of 2.2and a median of 7.

Nearly half of participating students (48.9%) rated their interesting in learning about CAM as ≥8 on a scale from 1-10 (1 = not interested at all, 5-6 I’m somewhat interested, 10 = I’m extremely interested). The average score was 7.1 with a standard deviation of 2.4 and a median of 7 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of respondents rating their overall attitude toward and interest in learning about CAM on a scale from 1-10(1 = I just don’t care for it; 5-6 I think it’s okay; 10 = I love it; n = 759).

Figure 1: Percentage of respondents rating their overall attitude toward and interest in learning about CAM on a scale from 1-10(1 = I just don’t care for it; 5-6 I think it’s okay; 10 = I love it; n = 759).

Senior students in their final semester before graduation had an average rating of 7.1 for their attitude toward CAM in general compared to 6.5 for pre-health professions students (Table 1). Nursing students reported the highest average rating (7.9) for attitude toward CAM in general as well as the highest average score for interest in learning about CAM among graduating seniors (8.1).

Graduating health professions students had a more positive attitude toward CAM than pre-health professions students (Wilcoxon Rank Sums Test, Chi-square = 15.9390, DF = 1, p < 0.0001). Graduating students also had a higher average score for their interest in learning about CAM practices than pre-health professions students (Wilcoxon Rank Sums Test, Chi-square = 5.5798, DF = 1, p = 0.0182).

|

|

Attitude score |

Interest score |

|

Pre-health professions |

6.5 |

7 |

|

Pre-nursing |

6.5 |

7 |

|

Health science |

6.4 |

6.8 |

|

Exercise science |

7.2 |

7.3 |

|

Public health |

6.6 |

7.3 |

|

Graduating seniors |

7.1 |

7.4 |

|

Nursing |

7.9 |

8.1 |

|

Community health |

6.6 |

7.5 |

Table 1: Average rating for general attitude toward (Attitude score) and interest in learning about CAM practices (Interest score) for different subpopulations of participants. Rating scales 1-10 with 10 being the highest score.

Respondents’ comments

Three-quarters of respondents (73.0%) explained why they chose a certain rating for their general attitude toward CAM. Most participants who rated their attitude as ≥8 based this rating on personal experience or having seen the benefits of CAM in others. For example, one student stated: “I am a strong believer in happy mind-happy body and that if you can control your mind, body and spirit, you can heal yourself. For example, I use yoga and meditating as a source of healing and I was able to get over my depression and anxiety”.

At the other end of the spectrum, participants often confessed to not knowing much or anything about CAM, or raised doubts about the effectiveness of these practices. One student expressed: “Holistic medicine is largely not a proven method of effective treatment. I support modern medicine that has been proven safe and effective for patients. That being said, standard medicine may not always be the best solution.” Another student stated that, in their opinion, CAM “is not based on science or medical practice. Most schemes are just to pay money to a quack spokesperson and health outcomes have been shown to be negatively impacted by the use of holistic health”.

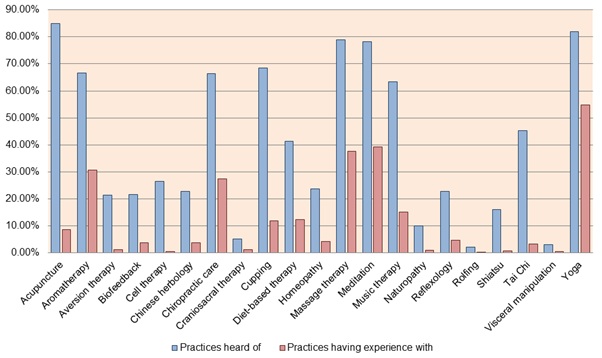

Experience with and knowledge of CAM in general

Nine out of ten respondents (89.4%) had heard of one or more of the CAM practices listed on the survey before (Figure 2). Practices two-thirds or more of students had heard of were acupuncture, yoga, massage therapy, meditation, cupping, aromatherapy, and chiropractic care. The least known practices were rolfing, visceral manipulation, and craniofacial therapy.

Three-quarters of respondents (76.1%) had previous experience with one or more CAM practice. Yoga was by far the most named practice, followed by meditation; massage therapy, aromatherapy and chiropractic care. Less than one percent of respondents reported experience with rolfing, cell therapy, visceral manipulation, or shiatsu.

Participants who had personal experience with CAM practices had an average rating for their attitude toward CAM of 6.8 (±2.2) and an average score for interest in learning about CAM of 7.0 (±2.4).

Figure 2: Percentage of respondents having heard of or having personal experience with specific CAM practices.

Figure 2: Percentage of respondents having heard of or having personal experience with specific CAM practices.

Attitude toward and knowledge of specific CAM practices

Participants were asked to rate their knowledge of individual practices they had heard of (How well do you think you know…?) on a scale from 1-10 (1 = I’ve heard about it; 5-6 = I have a pretty good idea what it is; 10 = I know everything there is to know). Respondents felt they knew yoga best, closely followed by massage therapy, chiropractic care, and meditation. Two-thirds of practices participants had heard of received average scores of less than 5.0, indicating a low level of knowledge about them (Table 2).

Practices respondents had personal experience with received higher scores across the board. Massage therapy, chiropractic care, and cupping received the highest average scores; cell therapy and shiatsu the lowest scores.

Participants who indicated that they had heard of a specific practice were asked to rate their attitude toward this practice (How would you rate your attitude towards…?) on a scale from 1 to 10 (see above). The highest rated practices were massage therapy, yoga, chiropractic care, meditation, music therapy and diet-based therapy (Table 2). Aversion therapy, reflexology, rolfing, shiatsu, and visceral manipulation were the lowest rated practices.

Participants who had personal experience with CAM gave the practices they were familiar with higher ratings. Eleven of 21 listed practices received an average rating of higher than 8.0 with massage therapy having the highest rating, followed by diet-based therapy, music therapy, chiropractic care, and naturopathy.

|

|

Practices heard of |

Practices experience with |

||

|

Practice |

Attitude score |

Knowledge score |

Attitude score |

Knowledge score |

|

Acupuncture |

5.7 |

4.4 |

7.4 |

6 |

|

Aromatherapy |

6.4 |

5.4 |

8.1 |

7 |

|

Aversion therapy |

4.2 |

3.4 |

7.1 |

6.8 |

|

Biofeedback |

5.3 |

4.1 |

7.2 |

7 |

|

Cell therapy |

5 |

3 |

4.3 |

4 |

|

Chinese herbology |

5.3 |

3.8 |

7.3 |

5.8 |

|

Chiropractic care |

7.3 |

6.5 |

8.4 |

7.6 |

|

Craniosacral therapy |

5.3 |

4.3 |

6.7 |

6 |

|

Cupping |

5.6 |

4.9 |

8 |

7.6 |

|

Diet-based therapy |

6.9 |

5.8 |

8.6 |

7.4 |

|

Homeopathy |

5.4 |

4.3 |

8 |

6.9 |

|

Massage therapy |

7.8 |

6.6 |

8.9 |

7.7 |

|

Meditation |

7.2 |

6.5 |

8.1 |

7.3 |

|

Music therapy |

6.9 |

5.7 |

8.5 |

7.4 |

|

Naturopathy |

5.9 |

4.8 |

8.4 |

7.3 |

|

Reflexology |

4.4 |

4.5 |

6 |

6.8 |

|

Rolfing |

4.6 |

4.5 |

-- |

-- |

|

Shiatsu |

4.7 |

3.1 |

7.5 |

5.5 |

|

Tai Chi |

5 |

3.5 |

7.6 |

6.6 |

|

Visceral manipulation |

4.7 |

3.7 |

8 |

7 |

|

Yoga |

7.6 |

6.8 |

8.2 |

7.3 |

Table 2: Average rating for attitude toward (Attitude score) and knowledge of (Knowledge score) specific CAM practices for practices respondents had heard of or had personal experience with. Rating scales 1-10 with 10 being the highest score.

CAM as part of professional training and practice

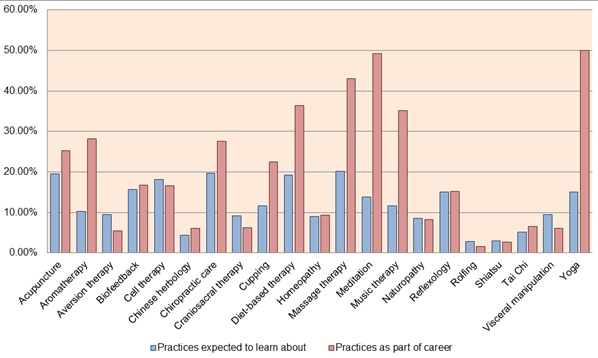

Close to half of survey respondents (47.1%) expected to learn about one or more CAM practices during their professional education (Figure 3). The practices most students expected to learn about were massage therapy, chiropractic care, acupuncture, diet-based therapy, and cell therapy. Tai chi, Chinese herbology, shiatsu and rolfing were the practices named by the fewest students.

Of 185 graduating seniors who answered the question ‘Did you learn about holistic medicine practices in your major?’89 (48.1%) answered with‘yes.’Most students learned about CAM in one or more classes in their major (71.4%) only; the others (28.6%) learned about CAM during clinical assignments as well. When asked which CAM practices they had learned about, respondents named meditation and music therapy most often (28.1% each), followed by biofeedback and aromatherapy (27.0% each), and acupuncture and yoga(24.7% each). Cell therapy, visceral manipulation, and craniofacial therapy were taught to less than 2.5% of students; no student reported learning about rolfing.

Three-quarters of students who answered the question ‘Do you expect to include aspects of holistic medicine in your future career as a health professional? ’chose ‘yes’ (76.4%).The top five practices these students planned on making part of their career were yoga (49.9%), meditation (49.2%), massage therapy (43.0%), diet-based therapy (36.4%) and music therapy (35.1%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.Percentage of respondents who expected to learn about specific CAM practices during their professional training and planned on making they part of their professional career.

Figure 3.Percentage of respondents who expected to learn about specific CAM practices during their professional training and planned on making they part of their professional career.

Discussion

Comparing the results of previous studies from the United States and other countries with the findings of our study is not straight forward because the studies used different lists of CAM practices to adjust for societal or cultural factors. Still, the results of our study are in line with previous studies that included undergraduate health professions students.

Attitude toward and interest in CAM in general

In our study, the overall attitude of participants toward and interest in learning about CAM practices was generally positive with graduating seniors recording higher scores than pre-health professions students. Zimmerman and Kandia (2012), Liu et al., (2014) and Nguyen et al., (2016) reported positive attitudes toward CAM among undergraduate students in the United States [18,19,21]. Studies that included nursing students at American universities by Halcón et al., (2003), Kim et al., (2006), Booth-Laforce et al., (2010) and Reuter, Turello & Brister (2021) also described overall positive attitudes toward CAM [23-26]. Radi et al., (2019) surveyed undergraduate students in Jordan, Subramanian & Midha (2016) in the US, England and India, Onal, Sahin & Inanc (2016) in Turkey, and Ditte et al., (2011) in Germany [3,15,27,28]. They all reported overall positive attitudes toward CAM, although there were differences between students in different majors. For example, among the students in the study by Radi et al., (2019), engineering students were the most skeptical, and medical students felt more positive the farther they had advanced in their education [16].

Nursing students reported the highest average rating for attitude toward CAM in general as well as the highest average score for interest in learning about CAM among graduating seniors. Kreitzer et al., (2002) also found that nursing students at the University of Minnesota were generally more positive about CAM than medicine or pharmacy students [29]. Comparing nursing and medical students at a Turkish university, Yildrim et al., (2010) reported more positive attitudes for nursing students than medical students towards CAM [30]. Among undergraduate students in China, students in lower level courses had a stronger desire to learn about CAM than those in higher level courses; overall three-quarters of students desired to learn about CAM [31].

Experience with and knowledge of CAM in general

Not all previous studies reported the same level of experience with or knowledge of CAM in general our study respondents indicated. Only 55% of participants in the study of Liu et al., (2014) had used CAM within the past 12 months and less than half of nursing students in a Canadian study had experience with CAM [19,32]. However, the results of our study may have been influenced by students having learned about and gained personal experience with CAM practices in upper level classes and clinical assignments in their programs.

Attitude toward and knowledge of specific CAM practices

As already mentioned above, previous studies used different lists of CAM practices than our study, making it difficult to compare the results. Our participants felt they knew yoga, massage therapy, chiropractic care, and meditation best, and awarded the highest ratings for attitude toward CAM practices to massage therapy, yoga, chiropractic care, meditation, music therapy, and diet-based therapy. The students in the study by Zimmerman & Kandia (2012) indicated familiarity with and knowledge of complementary and alternative herbal supplements such as gingko, ginseng, St. John's wort, garlic, Echinacea, and cinnamon [18]. A study including students from the U.S., UK, and India reported that dietary and vitamin supplements, massage, yoga, meditation, herbal medicine, and homeopathy as CAM practices with the highest prevalence overall [3]. Saudi Arabian students considered prayers/spirituality, massage therapy, nutritional supplements, cupping, herbal medicine, and yoga as most effective [17]. The most well-known CAM practices among medical students in a Turkish study were herbal treatment, acupuncture, hypnosis, massage therapy, and meditation [33]. Baugniet, Boon & Ostbye (2000) reported that herbal medicine, aromatherapy, and homeopathy were the top three CAM therapies among the students in their study [33]. In the same study, knowledge ratings were highest for chiropractic care, massage therapy, acupuncture, and herbal medicine, and lowest for homeopathy, faith healing, and reflexology. The nursing students in the study by Uzun& Tan (2004) showed good knowledge of massage therapy, diet, vitamins, herbal products, and praying [34].

CAM as part of professional training and practice

While none of the previously published studies provided information on which CAM practices students would like to learn about, some of them report on whether faculty included CAM practices in the curriculum and whether students intended to integrate CAM practices into their future careers. For example, six out of ten nursing students in a Turkish study wanted CAM to be integrated into the nursing curriculum and planned on using it in their clinical practice [34]. Similarly, Kim et al., (2006) reported that more than 65% of nursing students and faculty included in their study agreed that clinical nurse specialists and nurse practitioners should include the use of CAM in their practice [24]. Ninety percent of medical, nursing, and pharmacy faculty and students surveyed by Kreitzer et al., (2002) expressed that clinical care should integrate the best of both conventional and CAM practices [29]. Likewise, three-quarters of health professional students in a Saudi Arabian study believed in the use of CAM for the mental and spiritual aspects of health [17]. More than sixty percent of participants in a study by Zimmerman & Kandia (2012) thought that conventional medicine could benefit from integration with CAM and that medical professionals should integrate CAM into healthcare practices [18].

The main limitation of our study was using an investigator-developed list of CAM practices and survey tools. Also, collecting data from students at a medium-sized university in the southern United States and having a relatively small sample of pre-health professions and health professions students may prevent the results from being generalized for all undergraduates in the United States. Additionally, participants may not have provided accurate information thereby introducing bias into the results. Students’ answers may also have been influenced by learning about CAM practices in courses and during clinical assignments. Nevertheless, this study offers valuable insights into pre-health professions and health professions students’ knowledge of and attitudes toward CAM practices.

Conclusion

A majority of pre-health professions and graduating health professions students has positive attitudes toward CAM in general and is interested in learning about CAM practices in their chosen major. Health professions students had a more positive attitude toward CAM than pre-health professions students and expressed more interest in learning about CAM practices than pre-health professions students. Most students report previous experience with one or more CAM practices and planned on making CAM practices part of their future careers. Students in their last semester before graduation reported greater knowledge of more CAM practices due to exposure to such practices in upper level courses and clinical assignments.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The author’s confirm that the research presented in this article met the ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements, of the United States and received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Florida Gulf Coast University.

Funding

The authors did not receive funding for this study and have full control of all primary data.

References

- Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL (2015) Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl Health Stat Report 79: 1-16.

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine (2021) Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s In a Name? NIH, USA.

- Subramanian K, Midha I (2016) Prevalence and Perspectives of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among University Students in Atlanta, Newcastle upon Tyne, and New Delhi. Int Sch Res Notices 2016: 9309534.

- Stussman BJ, Black LI, Barnes PM, Clarke TC, Nahin RL (2015) Wellness-related use of common complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2012. Natl Health Stat Report 85: 1-12.

- Stussman BJ, Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Ward BW (2020) S. Physician Recommendations to Their Patients about the Use of Complementary Health Approaches. J Altern Complement Med 26: 25-33.

- Sohn PM, Cook CAL (2002) Nurse practitioner knowledge of complementary alternative health care: foundation for practice. J Adv Nurs 39: 9-16.

- Hall H, Leach M, Brosnan C, Collins M (2017) Nurses' attitudes towards complementary therapies: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Int J Nurs Stud 69: 47-56.

- Li B, Forbes TL, Byrne J (2017) Integrative medicine or infiltrative pseudoscience? Surgeon 16: 271-277.

- Tabish SA (2008) Complementary and Alternative Healthcare: Is it Evidence-based? Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2: V-IX.

- Kanadiya MK, Klein G, Shubrook JH Jr. (2012) Use of and attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine among osteopathic medical students. J Am Osteopath Assoc 112: 437-446.

- Awad AI, Al-Ajmi S, Waheedi MA (2012) Knowledge, perceptions and attitudes toward complementary and alternative therapies among Kuwaiti medical and pharmacy students. Med Princ Pract 21: 350-354.

- Loh KP, Ghorab H, Clarke E, Conroy R, Barlow J (2013) Medical students' knowledge, perceptions, and interest in complementary and alternative medicine. J Altern Complement Med 19: 360-366.

- Ameade EP, Amalba A, Helegbe GK, Mohammed BS (2016) Medical students’ knowledge and attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine - A survey in Ghana. J Tradit Complement Med 6: 230-236.

- Joyce P, Wardle J, Zaslawski C (2016) Medical student attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in medical education: a critical review. J Complement Integr Med 13:333-345.

- Onal O, Sahin DS, Inanc BB (2016) Should CAM and CAM Training Programs Be Included in the Curriculum of Schools That Provide Health Education? J Pharmacopuncture 19: 344-349.

- Radi R, IsleemU, Al Omari L, Alimoglu O, Ankarali O, et al. (2019) Attitudes and barriers towards using complementary and alternative medicine among university students in Jordan. Complement Ther Med 41: 175-179.

- Khan A, Ahmed ME, Aldarmahi A, Zaidi SF, Subahi AM, et al. (2020) Awareness, Self-Use, Perceptions, Beliefs, and Attitudes toward Complementary and Alternative Medicines (CAM) among Health Professional Students in King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020: 7872819.

- Zimmerman C, Kandiah J (2012) A pilot study to assess students' perceptions, familiarity, and knowledge in the use of complementary and alternative herbal supplements in health promotion. AlternTher Health Med 18: 28-33.

- Liu MA, Huynh NT, Broukhim M, Cheung DH, Schuster TL, et al. (2014) Determining the attitudes and use of complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine among undergraduates. J Altern Complement Med 20: 718-726.

- Mhatre S, Artani S, Sansgiry S (2011) Influence of benefits, barriers and cues to action for complementary and alternative medicine use among university students. J Complement Integr Med 2011: 8.

- Nguyen J, Liu MA, Patel RJ, Tahara K, Nguyen AL (2016) Use and interest in complementary and alternative medicine among college students seeking healthcare at a university campus student health center. Complement Ther Clin Pract 24: 103-108.

- Johnson SK, Blanchard A (2006) Alternative medicine and herbal use among university students. J Am Coll Health 55: 163-168.

- Halcón LL, Chlan LL, Kreitzer MJ, Leonard BJ (2003) Complementary therapies and healing practices: faculty/student beliefs and attitudes and the implications for nursing education. J Prof Nurs 19: 387-397.

- Kim SS, Erlen JA, Kim KB, Sok SR (2006) Nursing students' and faculty members' knowledge of, experience with, and attitudes toward complementary and alternative therapies. J Nurs Educ 45: 375-378.

- Booth-Laforce C, Scott CS, Heitkemper MM, Cornman BJ, Lan M, et al. (2010) Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) attitudes and competencies of nursing students and faculty: results of integrating CAM into the nursing curriculum. J Prof Nurs 26: 293-300.

- Reuter PR, Turello AE, Holland LM (2021) Experience with, Knowledge of, and Attitudes toward Complementary and Alternative Medicine among pre-nursing and nursing students. Holist Nurs Pract 35: 211-220.

- Onal O, Sahin DS, Inanc BB (2016) Should CAM and CAM Training Programs Be Included in the Curriculum of Schools That Provide Health Education? J Pharmacopuncture 19: 344-349.

- Ditte D, Schulz W, Ernst G, Schmid-Ott G (2011) Attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine among medical and psychology students. Psychol Health Med 16: 225-237.

- Kreitzer MJ, Mitten D, Harris I, Shandeling J (2002) Attitudes toward CAM among medical, nursing, and pharmacy faculty and students: a comparative analysis. Altern Ther Health Med 8: 44-53.

- Yildirim Y, Parlar S, Eyigor S, Sertoz OO, Eyigor C, et al. (2010) An analysis of nursing and medical students' attitudes towards and knowledge of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). J Clin Nurs 19: 1157-1166.

- Xie H, Sang T, Li W, Li L, Gao Y, et al. (2020) A Survey on Perceptions of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among Undergraduates in China. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020: 9091051.

- Baugniet J, Boon H, Ostbye T (2000) Complementary/alternative medicine: comparing the view of medical students with students in other health care professions. Fam Med 32: 178-184.

- Akan H, Izbirak G, Kaspar EC, Kaya CA, Aydin S, et al. (2012) Knowledge and attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine among medical students in Turkey. BMC Complement Altern Med 12: 115.

- Uzun O, Tan M (2004) Nursing students' opinions and knowledge about complementary and alternative medicine therapies. Complement Ther Nurs Midwifery 10: 239-244.

Citation: Reuter PR, Holland LM, Turello AE (2021) Health Professions Students’ Knowledge of and Attitude toward Complementary and Alternative Medicine. J Altern Complement Integr Med 7: 184.

Copyright: © 2021 Peter R Reuter, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.