How well are Patients doing Post-Alcohol Detox in Bristol? Results from the Outcomes Study

*Corresponding Author(s):

Ben SessaImperial College London, Centre For Neuropsychopharmacology, Division Of Brain Sciences, Faculty Of Medicine, United Kingdom

Email:bensessa@gmail.com

Abstract

Bristol Specialist Drug and Alcohol Services (BSDAS) carry out over 450 community-based detoxifications per year, with 85% of patients being alcohol free after the 14-day program. But there is a paucity of information collected on the different treatment pathways offered after initial detoxification. This paper presents the results of an observational study that followed a group of 12 patients from the start of their community detox for 9 months, collecting information about outcomes. In respect of drinking behaviour, results post-alcohol detoxifications were poor. Three months post detox, 8 out of the 12 participants had relapsed to drinking. Six participants had a second, and one participant had a third detox within the 9-month follow up period. Given the burden of alcohol use disorder (AUD) on the population of Bristol, this study is an important step on the journey of developing new and innovative treatments for this population. And in the context of the current Covid 19 pandemic, attention to the issue of best management of AUD has become even more pertinent.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol dependence

In 2018 alone there were over 7500 deaths directly related to alcohol in the UK (ONS 2019) [1], a figure likely to be closer to 15,000 if diseases related to alcohol use were also included [2]. Recent data also indicates this is a growing problem, with alcohol related inpatient admissions increasing 60% from 2008 to 2018 [3]. Globally AUD is the third leading cause of disability in Europe [4]. Alcohol use disorder not only affects the patients themselves, but also those around them, adding to the pain, suffering and costs associated with alcohol dependency.

Alcohol Dependence Syndrome (sometimes referred to as alcohol dependence) is a psychiatric disorder in which individuals have become psychologically and physically addicted to alcohol. In the UK, the prevalence of alcohol dependence is about 4%; 6% of men and 2% of women. Typically alcohol dependence is characterised by (often serious) withdrawal symptoms on cessation of alcohol, or drinking to avoid withdrawal symptoms, tolerance and the persistent desire to drink and continuing drinking despite negative consequences [5]. The impact of alcohol dependence and AUD is widespread, encompassing alcohol related illness and injuries as well as significant social impacts to family, friends and wider community. Taking into account alcohol related health disorders and disease, crime and anti-social behaviour, accidents, loss of productivity in the workplace and domestic problems, the Department of Health estimates that alcohol misuse is now costing at least £20 billion a year in England alone [6].

Detoxification and current treatment options in Bristol

The first stage of addressing alcohol dependence is the cessation of alcohol consumption. Standard guidelines are provided by NICE [5], which outline the assessments that should be undertaken before detoxification, and the treatment options available during and after withdrawal to help maintain abstinence. The primary goal of detox programs, the majority of which now take place in the community, are to manage the physical withdrawal symptoms from alcohol [7], which on average takes approximately 10-14 days. While community detoxification programs are now relatively successful in achieving withdrawal from alcohol with few serious medical consequences [8], this represents only the first stop in managing alcohol dependency. Patients treated by BSDAS can subsequently be offered a range of services and treatments post-detox depending on their individual needs. These include: Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART), Dual Recovery Anonymous (DRA), Relapse Prevention (RP), Training Education Vocational Employment (TEVE), Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), and psychodynamic psychotherapy (rare). There are also some residential rehabilitation and ‘dry house’ services for those requiring more intensive input and a range of faith-based recovery programs. Relapse prevention medications are also offered to many of those completing the detoxification e.g., acamprosate, disulfiram, naltrexone, baclofen.

Although a large number of treatments are available for alcohol dependence in Bristol and more widely, research shows that long term outcomes remain poor, with relapse rates of up to 60% at 12 months and 80% at 3 years [9,10]. A meta-analysis of 361 controlled studies of treatments for alcohol dependence in 2002 identified 46 possible interventions [11]. Interventions were ranked according to rates of abstinence achieved. The brief intervention approach ranked highest. Those classed as brief interventions were those delivered over a brief time period, usually 1 or 2 sessions. Typically these involved a form of advice-giving about reducing alcohol consumption and often a self-help booklet to take away. Importantly, in this review, all treatments that used a specific modality (e.g. “self-control training”) however brief, were classified as a specific intervention and not included in the brief intervention category. Motivational enhancement therapy was ranked second, which is a counselling approach that helps individuals resolve their ambivalence about engaging in treatment and stopping their drug use. The motivational enhancement approach aims to evoke rapid and internally motivated change, rather than guide the patient stepwise through the recovery process. Pharmacotherapy with the GABA agonist acamprosate and the opiate antagonist naltrexone ranked 3rd and 4th respectively. The lowest ranked approaches were designed to educate, confront, shock or foster insight regarding the nature of alcoholism. From this meta-analysis psychotherapy produced the best outcomes. In addition it is important to note that studies have indicated that repeated detoxifications are associated with more complications [12]. This highlights further the need for successful treatments to help patients remain abstinent after their first detoxification and avoid the complications that can occur with repeated detoxifications.

METHODS

Approvals

This study received ethics approval from South West - Exeter - REC and was sponsored by Imperial College London. Funding was provided by The Alexander Mosley Charitable Trust. Participant travel expenses for were reimbursed, and when required taxis were provided. Refreshments were provided during study visits.

Rationale for study design

Approximately 450 patients per annum present to the BSDAS for community detoxification. Audit data from clinical notes undertaken in 2013 indicates that while significantly better than neighboring services, formal assessment data, such as that provided by the AUDIT questionnaire is available for less than half of the patients pre-detoxification. Information about patients after detoxification is even more sparse and difficult to collect. The main reason for this is that post-detox, patients are directed into a range of community and primary care based therapeutic programs which do not necessarily report into the same clinical note systems, with some not being required to report attendance or patient status at all. Because of this, external effort must be made in order to collect high quality data about outcomes for these patients after detoxification, as reliance on clinical notes is not a feasible option.

Even for research teams, collecting follow-up data in this group of patients can be difficult, with typical attrition rates of 10-35% [13]. Recent studies highlight the pitfalls of using statistical analysis to predict outcomes for those lost to follow-up [13], emphasising the importance of collecting good quality long term outcome data in these studies [14]. Authors assessing attrition in this population suggest that enhanced contact with patients is likely to be advantageous. In this way, even if lost to follow-up, more information about prior function would allow better prediction and accuracy of outcome during analysis [15].

To explore some of these methodological issues, we used a prospective approach to assessing different methods of data collection. We compared the use of monthly follow-up calls with simply inviting patients to follow-up visits to ascertain if more close observation and contact could increase compliance and successful data collection. The sample size for this study is based on other studies in patients with alcohol dependence [16]. This study has been specifically designed to be representative of a patient cohort that would be eligible for interventional studies and who would be interested in taking part in research after detoxification from alcohol. We did not attempt to sub-analyse the outcomes for this wide range of treatments post-detox as this was beyond the scope of this project. We rather looked at the group as a whole in order to give a broad estimate of long-term outcome.

Study design

This was an observational, questionnaire based, follow-up study in patients undergoing a community alcohol detoxification at Bristol Drug and Alcohol services. Service users preparing for community alcohol detoxification were invited to take part. Patients attend a screening visit prior to detoxification, a baseline visit after detoxification and at this point were randomised into two groups. The standard observation group had a face to face meeting with the study researchers at 3, 6 and 9 months. The close observation group had additional monthly phone calls with a researcher.

Outcome measurements were made through the use of clinical interview:- the Time Line Follow-back drink diary method, urine tests for alcohol and drugs of abuse and questionnaires to measure quality of life, anxiety, depression, thoughts about alcohol use and sleep. For those in the close observation group, drinking behaviour was assessed via the Time Line Follow-back (TLFB) at each monthly call.

Assessments and Questionnaires used in the Outcomes Study

- The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview 5 (MINI 5) [17], to screen for comorbid psychiatric disorders. Completed once, at screening.

- The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) [18], to screen for acute and recent suicide and self-harm thoughts and behaviours. Completed at screening only.

- The Alcohol Dependence Syndrome section of the SCID-5-CT (Clinical Trials Version) [19], completed once, at screening.

- The Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SADQ) [20] to measure the presence and level of alcohol dependence. Completed once, at screening.

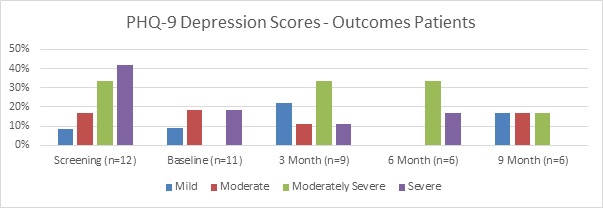

- The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [21]. A brief self-report scale for depressive symptom severity. Administered at screening, baseline and at 3-, 6- and 9-months follow-up.

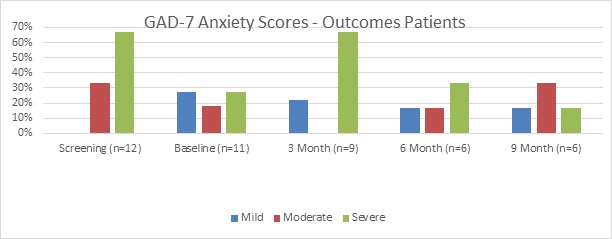

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) [22], a brief 7 item self-report scale, administered at screening, baseline and at 3-, 6- and 9-months follow-up.

- The Time-Line Follow Back (TLFB) [23], to assess daily drinking and recreational drug use over time. Performed retrospectively at baseline to assess the prior 3-months’ drinking behaviour, then completed throughout the study, on a daily basis by the participant at home. Then reviewed formally at 3, 6 and 9 months follow up. Those in the close observation group were also telephoned phoned monthly by the study team to collect the outcomes of their last 30 days TLFB entries.

- The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol – Revised Version (CIWA-Ar) [24], to assess the severity of alcohol withdrawal, completed once at baseline after detox.

- The Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS) [25], to assess frequency, intensity and duration of thoughts about drinking, completed at the screening and baseline assessment and at 3, 6- and 9-months follow-up.

- Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS) [26], to measure obsessive and compulsive thoughts in relation to alcohol. Completed at the screening and baseline assessment and at 3-, 6- and 9-months follow-up.

- Short Inventory of Problems for Alcohol (SIP) [27], to assess the self-attributed consequences of drinking, completed at screening, 3-, 6- and 9-months follow-up.

- Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. (PSQI) [28], to assess the level of sleep disturbance, completed at screening, the baseline assessment and at 3-, 6- and 9-months follow-up.

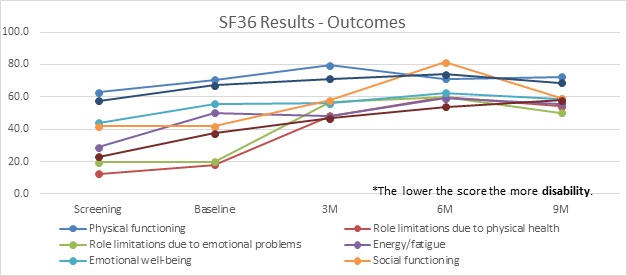

- The Short Form (36) Health Survey (SF-36), a gold standard patient-reported measure of quality of life, completed at baseline, 3, 6 and 9 months.

RECRUITMENT

Recruitment: Recruitment was conducted via mental health practitioners within BSDAS. Potentially eligible patients were sent an invitation letter with consent to contact slip and if interested in taking part they were given the patient information sheet. After a short phone call with verbal consent to check eligibility, patients were invited for a formal screening visit.

Inclusion criteria: Adults with a primary diagnosis of alcohol dependence syndrome (as defined by DSM-5), successful alcohol detoxification (no longer consuming any alcoholic substances following detoxification), access to a supportive significant other or locator who could accompany the participant to study visits if required and who could be contacted by the study team in the event of the participant being uncontactable, not taking any regular psychotropic medications except those commonly used during and after the detoxification, which include: mirtazapine, pregabalin, gabapentin, benzodiazepines and Z-hypnotics, baclofen, acamprosate, naltrexone and disulfiram.

Exclusion criteria: A history of, or a current, primary psychotic disorder, bipolar affective disorder type 1 or personality disorder, relevant abnormal clinical findings or medication at screening visit judged by the investigator to render subject unsuitable for study, presenting a serious suicide risk, regular user of drugs of abuse and (for females of childbearing age/potential) must not be pregnant or breast-feeding during the first 3 months of the study. All participants were free to withdraw at any time from the study without giving reasons and without prejudicing further treatment. If a patient withdrew from the trial their data continued to be treated as confidential and were be included in the final data analysis where appropriate.

Consent, screening and baseline visits: At screening participants underwent a full psychiatric assessment including the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview 5 (MINI 5) to screen for comorbid psychiatric disorders and diagnostic evaluation of presence of Alcohol Dependence Syndrome (DSM-5). Clinical data collection included years of alcohol dependence, complications and consequences. After detoxification, patients attended a baseline visit to confirm eligibility. During this visit, continued consent was confirmed, and vital signs reassessed (pulse, blood pressure etc.). There was a brief physical examination and ECG; blood samples will be taken for routine laboratory tests (urea and electrolytes, full blood count, liver function tests and Gamma-GT) unless recent blood test results were available. An assessment of physical signs of withdrawal was carried out using the revised Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Scale (CIWA-Ar) questionnaire [29]. An alcohol breath test was performed to ensure successful detoxification and dip-stick urinalysis for drugs of abuse. If female, dip-stick urinalysis for pregnancy was completed. Patients completed post-detoxification questionnaires. If eligible, patients were then randomised to receive close or limited follow-up. They were informed of which group they had been allocated to and dates and times for phone calls and follow-up interviews were agreed.

Follow-up methods

Telephone calls: Those in the close observation group were phoned approximately monthly to collect information about drinking behaviour and drug use if relevant, using the TLFB diary. If no contact could be made, the research team telephoned the significant other to collect basic information on drinking behaviour if known. If no contact with the study team was received after 4 weeks the patient was considered lost to follow-up, unless they contacted the study team at a later date.

Face-to-face Interviews: These occurred without any interference with post-detox treatment programs. Participants were invited to attend interviews at 3-, 6- and 9-months. Participants received a phone call or text reminder before the interview. At follow-up visits, participants were also asked to complete a urine test for drugs of abuse and a breathalyzer test for alcohol.

RESULTS

Patient Recruitment: Twenty-six patients from BSDAS were screened. Twelve patients were enrolled as eligible after screening and all 12 subsequently successfully completed a medical alcohol detox and were eligible at baseline. Twelve participants remained enrolled to give a full set of data at the 3-month follow-up point. By the time of the 6-month and 9-month follow-up points, ten patients remained still in contact with the study team to give final outcome data.

Patient demographics: Four women and eight men participated in the observational study. The average age when alcohol became problematic or of daily use was 22 years old. 67% of participants reported a history of blackouts secondary to their use of alcohol and 50% of participants reported that their use of alcohol had led to them experiencing vulnerable incidents.

Severity of alcohol use: At screening participants were drinking an average of 197 units of alcohol per week/day. All met criteria for alcohol use disorder and were eligible for community detoxification. Based on the Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire ten out of twelve patients expressed "severe alcohol dependence", one "moderate alcohol dependence" and one participant did not complete the questionnaire appropriately. All twelve of the patients eligible at screening subsequently completed an alcohol detox and were therefore eligible at baseline.

In terms of aftercare, all patients were offered individualized aftercare support including psycho-social interventions and anti-craving medications. Eleven of the twelve participants chose to engage with the psycho-social support available, with most engaging with at least two psycho-social interventions (PSIs) or peer support groups. One opted for anti-craving medication only. Two participants took anti-craving medication in combination with attending PSIs. Eight participants engaged with relapse prevention groups post-detox, three patients attended AA in the local community, four attended a CBT for anxiety and depression course (‘Moodjuice’), one received individual trauma-focused therapy and one went to a residential rehabilitation facility for 6 months after their third detox. Two participants returned to their previous paid employment and one commenced voluntary work. Other post-detox support that participants engaged with included SMART recovery groups, mindfulness group, photography course and cookery course (Figure 1).

DRINKING BEHAVIOUR OUTCOMES (AS MEASURED BY TLFB) UP TO 9-MONTHS

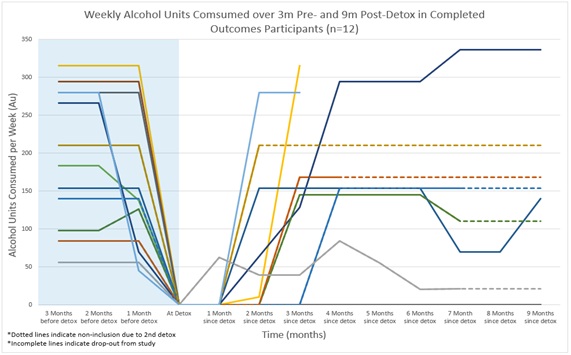

Figure 1: Individual drinking behaviour displayed as units of alcohol consumed per week (n=12). In the case of additional detoxification TLFB results are expressed as an extrapolation of drinking behaviour from the point of their initial relapse (dotted lines indicate the point). Incomplete lines indicate drop-out.

Figure 1: Individual drinking behaviour displayed as units of alcohol consumed per week (n=12). In the case of additional detoxification TLFB results are expressed as an extrapolation of drinking behaviour from the point of their initial relapse (dotted lines indicate the point). Incomplete lines indicate drop-out.

DISCUSSION

As predicted, there was a high rate of attrition, with only half (n=6) of the eligible patients who started the study (n=12) providing full datasets at the 9-month follow-up point. Of the twelve patients who had their first detox at baseline, five participants had a 2nd detox after the 3-month timepoint, and one of those five had a further, 3rd, detox before reaching the 9-month endpoint of the study. This makes analysis of the data at 9-months for the whole cohort difficult to interpret. For those that had additional detoxes, the TLFB results are expressed as an extrapolation of drinking behaviour outcomes from the point of their initial relapse after their first detox. TLFB data for the full dataset (n=12) is therefore only complete at the 3-months timepoint.

Six participants were randomised to the close observation group and received monthly telephone contact to discuss their drinking diary and general recovery progress in addition to face to face contact with the study team at 3-, 6- and 9-months. Six participants randomised to the standard observation group received the face to face 3-, 6- and 9-months contact only. In the close observation group, two participants dropped out whereas in the standard group there were no dropouts. Whilst complete dropout rates were low in this study (excluding those who relapsed); it appears that monthly telephone calls did not improve attrition or relapse rates.

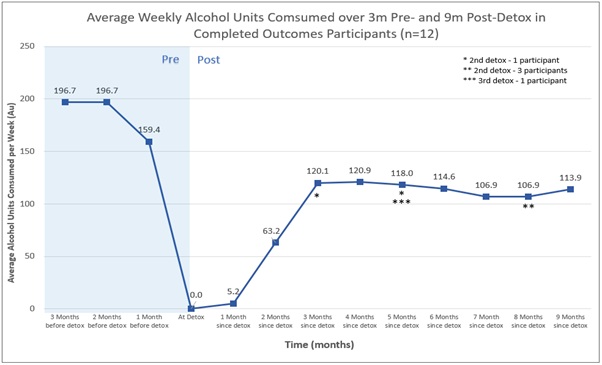

Despite BSDAS completing successful initial detoxes with 100% of participants and them all being offered comprehensive aftercare packages, the TLFB results indicate that the majority of patients had relapsed by 3-months and 50% of participants had at least one subsequent detox within the 9-month follow-up period. Even when the drinking behaviour data of those who had additional detoxes after the 3-month timepoint is taken into account, the average drinking behaviour (measured as units of alcohol consumed per week) remained as consistently high as at the 3-month timepoint (See Figure 2). These results are reflective of national and international outcomes for patients with AUD post-detox. And highlights that current treatments to maintain abstinence are poor.

Figure 2: Average (of Figure 1) Weekly alcohol consumption for all 12 patients up to 9-months post-detox

Figure 2: Average (of Figure 1) Weekly alcohol consumption for all 12 patients up to 9-months post-detox

Results of other outcome measures:

PHQ-9:

|

PHQ-9 Table |

|||||

|

Patient Count |

Screening (n=12) |

Baseline (n=11) |

3 Month (n=9) |

6 Month (n=6) |

9 Month (n=6) |

|

Mild Depression |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

|

Moderate Depression |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Moderately Severe Depression |

4 |

0 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

Severe Depression |

5 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

In respect of the other outcome measures, the results of the PHQ-9 (Figure 3) and GAD-7 (Figure 4) measures demonstrate expected high levels of depression and anxiety amongst this population of patients. Possibly unsurprisingly given the poor drinking behaviour results, levels of anxiety and depression remained significantly high throughout the 9-months of the study.

Figure 3: PHQ9 – Graph

Figure 3: PHQ9 – Graph

GAD-7

|

GAD-7 |

|||||

|

Patient Count |

Screening (n=12) |

Baseline (n=11) |

3 Month (n=9) |

6 Month (n=6) |

9 Month (n=6) |

|

Mild anxiety |

0 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Moderate anxiety |

4 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

Severe anxiety |

8 |

3 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

Figure 4: GAD-7 Graph

Figure 4: GAD-7 Graph

Interpretation of the rates of craving (PACS) and the obsessive-compulsive thoughts and behaviours associated with alcohol (OCDS) were difficult to interpret given the high drop-out rate from the sample. Both measures showed a significant reduction in these factors, suggesting participants had fewer obsessive-compulsive thoughts and behaviours and fewer cravings over the course of the 9-months. However, this was clearly not reflected in their drinking behaviour, which, tended to worsen from the 3-month timepoint onwards.

And finally, the results of the SF-36 (Figure 5) measure suggest that for those that provided results to 9-months, despite the majority of patients relapsing to high levels of drinking by 3-months (and continuing high rates of drinking, even if they had 2nd or 3rd detoxes) their overall level of psycho-social functioning appears to have improved over the course of the 9-months. This observation is likely skewed by the incomplete dataset at 9-months [30,31].

Figure 5: SF-356 Graph

Figure 5: SF-356 Graph

SF-36

|

SF36 Table |

|||||

|

Screening |

Baseline |

3M |

6M |

9M |

|

|

RESULTS |

SCORE |

SCORE |

SCORE |

SCORE |

SCORE |

|

Physical functioning |

62.7 |

70.5 |

79.4 |

71.3 |

72.5 |

|

Role limitations due to physical health |

12.5 |

17.9 |

48.4 |

60.0 |

54.2 |

|

Role limitations due to emotional problems |

19.4 |

20.0 |

56.5 |

60.0 |

50.0 |

|

Energy/fatigue |

28.8 |

50.0 |

48.1 |

59.0 |

55.8 |

|

Emotional well-being |

44.0 |

55.6 |

56.0 |

62.5 |

58.7 |

|

Social functioning |

41.7 |

41.7 |

57.8 |

81.3 |

59.1 |

|

Pain |

57.7 |

67.3 |

71.3 |

74.0 |

68.8 |

|

General health |

22.9 |

37.5 |

46.6 |

53.8 |

57.8 |

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study may be understood in the context of some limitations. A small sample size can make it difficult to draw firm conclusions and for the data to be generalizable to the wider cohort of BSDAS patients, or to UK-wide alcohol treatment services, as only a small number of patients from one Bristol service were observed. However, this research shines an important light on the difficulties experienced by people with AUD post community support medical detox. The BSDAS and allied services provide a broad and quality service for its large population of people struggling with AUD in the Bristol area including successful detoxification and a variety of psycho-social and pharmacological aftercare support. However, the results from this study indicate that outcomes for patients remains poor. This data will provide crucial information to local teams and will be used both by the trust in terms of service provision as well as by research teams to inform future study design. Given the tremendous burden of alcohol misuse disorders on the population of Bristol, we feel this study is an important first step on the journey of developing new and innovative treatments for this worthy population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Huge gratitude is paid to the Alexander Mosely Trust who funded this, all the staff at CRIC and Colston Fort and additional thanks to Dr Chloe Sakal for clinical work.

REFERENCES

- Clay JM, Parker MO (2020) Alcohol use and misuse during the COVID-19 pandemic: a potential public health crisis? The Lancet: Public Health 5: e259.

- Home Office (2013) Next Steps following the Consultation on Delivering the Government’s Alcohol Strategy Home Office. Home Office, London, UK.

- NHS (2020) Part 1: Alcohol-related hospital admissions Digital Statistics on Alcohol, England, UK.

- Rehm J (2011) The risks associated with alcohol use and alcoholism. Alcohol Res Health 3: 135-143.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, NICE (2013) Alcohol-use disorder diagnosis and clinical management of alcohol-related physical complications CG100. NICE, London, UK.

- Public Health England (2016) The Public Health Burden of Alcohol and the Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Alcohol Control Policies: An evidence review. Public Health England, England, UK.

- Jesse S, G Bråthen, M Ferrara, M Keindl, Menachem EB, et al. (2017) Alcohol withdrawal syndrome: mechanisms, manifestations and management. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 135: 4-16.

- Soyka M, Horak M (2004) Outpatient alcohol detoxification: implementation efficacy and outcome effectiveness of a model project. Eur Addict Res 10: 180-187.

- Evren C, Durkaya M, Dalbudak E, Çelik S, Çetin R, et al. (2010) Factors related with relapse in male alcohol dependents: 12 months follow-up study. Düsünen Adam: J Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 23: 92-99.

- Moos RH, Moos BS (2006) Rates and predictors of relapse after natural and treated remission from alcohol use disorders. Addiction 101:212–222.

- Miller WR, Wilbourne PL (2002) Mesa Grande: a methodological analysis of clinical trials of treatments for alcohol use disorders. Addiction 97: 265-277.

- Malcolm R, Roberts JS, Wang W, Myrick H, Anton RF (2000) Multiple previous detoxifications are associated with less responsive treatment and heavier drinking during an index outpatient detoxification. Alcohol. 22: 159-164.

- Hallgren KA, Witkiewitz K (2013) Missing data in alcohol clinical trials: a comparison of methods. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37: 2152-2160.

- Witkiewitz K, Finney JW, Harris AH, Kivlahan DR, Kranzler HR (2015) Recommendations for the Design and Analysis of Treatment Trials for Alcohol Use Disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39:1557-1570.

- Scott CK (2004) A replicable model for achieving over 90% follow-up rates in longitudinal studies of substance abusers. Drug and alcohol dependence 74: 21-36.

- Paterson LM, Flechais RSA, Murphy A, Reed LJ, Abbott S, et al. (2015) The Imperial College Cambridge Manchester (ICCAM) platform study: an experimental medicine platform for evaluating new drugs for relapse prevention in addiction. Part A: study description. J Psychopharmacol 29: 943-960.

- Pettersson A, Modin S, Wahlström R, Hammarberg SAW, Krakau I (2018) The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview is useful and well accepted as part of the clinical assessment for depression and anxiety in primary care: a mixed-methods study. BMC Fam Pract 19: 19.

- Mundt JC, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Federico M, Mann JJ, et al. (2013) Prediction of suicidal behavior in clinical research by lifetime suicidal ideation and behavior ascertained by the electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. J Clinical Psychiatry 74: 887-893.

- First MB, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS, Spitzer PL (1997) Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders, (SCID-II). American Psychiatric Press, Washington, USA.

- Heather N, Brodie J, Wale S, Wilkinson G, Luce A, et al. (2000) A randomized controlled trial of Moderation-Oriented Cue Exposure. J Studies on Alcohol 61: 561-557.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001) The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16: 606-613.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B (2006) A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166: 1092-1097.

- Sobell LC, Agrawal S, Annis H, Velazquez HA, Echeverria L, et al. (2001) Cross-cultural evaluation of two drinking assessment instruments: Alcohol timeline followback and inventory of drinking situations. Substance Use & Misuse 36: 313-331.

- Williams D, Lewis J, McBride A (2001) A comparison of rating scales for the alcohol-withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol and Alcoholism 36: 104-108.

- Flannery BA, Volpicelli JR, Pettinati HM (1999) Psychometric prop- erties of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23: 1289-1295.

- Schmidt P, Helten C, Soyka M (2011) Predictive value of obsessive-compulsive drinking scale (OCDS) for outcome in alcohol-dependent inpatients: results of a 24-month follow-up study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 6: 14.

- Kiluk BD, Dreifuss JA, Weiss RD, Morgenstern J, Carroll KM (2013) The Short Inventory of Problems - revised (SIP-R): psychometric properties within a large, diverse sample of substance use disorder treatment seekers. Psychol Addict Behav 27:307-314.

- Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, Riemann D, Hohagen F (2002) Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. J Psychosomatic Research 53: 737-740.

- Kattimani S, Bharadwaj B (2013). Clinical management of alcohol withdrawal: A systematic review. Industrial psychiatry journal 22: 100-108.

- Saitz M, Mayo-Smith MF, Redmond HA, Bernard DR, Calkins DR (1994) Individualized treatment for alcohol withdrawal. A randomized double-blind controlled trial. JAMA 272: 519-523.

- The WHOQoL GROUP (1995) The World Health Organization Quality Of Life Assessment (WHOQoL): Position Paper From the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med 41: 1403-1409.

Citation: Sessa B, Higbed L, O’Brien S, et al. (2020) How well are Patients doing Post-Alcohol Detox in Bristol? Results from the Outcomes Study. J Alcohol Drug Depend Subst Abus 6:021.

Copyright: © 2020 Ben Sessa, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.