Hyporesponsiveness to Erythropoietin- Stimulating Agents: Targets of Management

*Corresponding Author(s):

Ahmed Yasin MD, FASNNephrology Division, Internal Medicine Department, Saudi German Hospital, Medina, Saudi Arabia

Email:nephrology20192019@gmail.com

Abstract

Anemia of different severity is manifested in around 80% of dialysis patients and its pathogenesis is of multifactorial nature. Relative insufficiency of erythropoietin leading to hyperproliferative erythropoiesis is considered the main underlying cause. Management of anemia has several therapeutic implications, including reasonable quality of life and avoidance of repeated blood transfusions, among others. Optimal maintenance of hemoglobin target levels is not easy, even with the implementation of different therapeutic options, including erythropoietin-stimulating agents (ESAs). Approximately 5–10% of patients are not responding adequately, despite incremental dosing of ESA therapy. That inadequate response has multiple heterogeneous causes, making anemia management rather difficult. Hyporesponsiveness to ESAs is a challenging problem requiring proper solution.

Keywords

Anemia; Dialysis; Erythropoiesis stimulating agents; Hemoglobin; Hyporesponsiveness; Resistance

Introduction

According to World Health Organization (WHO), anemia is defined as Hb level < 13 m/dl in adult males and postmenopausal females, and it is there if Hb levels <12 gm/dl for premenopausal females [1]. Renal anemia is a frequent complication in Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) patients with worse morbidity and mortality [2,3]. Its severity increases with progressive loss of kidney function, considering that 90% of Erythropoietin (EPO) is produced by the kidneys [4]. While almost 5% of CKD stage III patients have anemia, approximately 95% of hemodialysis patients develop anemia of certain degree [5]. Several causative factors are included in the pathogenesis of anemia in CKD patients, mainly the decreased production of EPO [6]. Following the US Food and Drug Administration’s approval of recombinant human EPO (rhuEPO) in 1989, the introduction of ESAs was a real revolution in renal anemia treatment [7]. More than 85% of hemodialysis patients were treated with ESA, according to USRDS 2020 Annual Data report. However, inadequate response to ESA therapy was reported in 5–10% of these patients [8].

Definitions

- Hyporesponsiveness resistance

The term hyporesponsiveness looks preferable to the term resistance for its more accuracy. Reduced response to ESA therapy is relative in most cases. So, the word hyporesponsiveness denotes the use of higher than usual ESA doses without achieving Hb target levels OR the need for incremental ESA doses to maintain target Hb levels [9].

According to KDIGO 2012 guidelines, ESA hyporesponsiveness denotes no increase in Hb following 1 month of weight-based dosing (initial type) and/or the need for two increments in ESA dose up to 50% more than the previous dose for achieving stable Hb levels(subsequent type) [10]. According to European Best Practice guidelines (2004), the maximum dose of EPO is 300 units/kg/week and 1.2 mcg/kg/week for darbepoetin alfa [11]. The ideal Hb level for hemodialysis patients is not well-defined. An accepted practice is to have maintenance of Hb target level between 10 and 11.5 gm/dL; in the same direction of KDIGO 2012 guidelines.

- ESA Resistance Index (ERI)

It is a mathematical representation of the complex relationship between the targeted Hb level and the required ESA dose. It is calculated as the ratio between the average weekly ESA dose/kg body weight and Hb (g/dl) level. Elevated ERI could be considered as a possible clue for modifiable causative factors underlying ESA hyporesponsiveness [12].

Epidemiology

The incidence of ESA hyporesponsiveness in hemodialysis patients is different from one country to another, ranging from 7.3 to 17.6%, with more prevalence compared with patients on peritoneal dialysis. ESA hyporesponsiveness was reported in 12.5% of hemodialysis patients and was strongly associated with higher mortality, iron and ESA use, and lower Hb levels as well. Around 15% of hemodialysis patients requiring high ESA doses consume 50% of total ESA therapy costs [13].

Etiology

Causes of anemia of ESA hyporesponsiveness are broadly related to 3 main categories: iron deficiency, inflammatory conditions, and bone marrow suppression. A summary of these causes is shown in Table 1.

|

Frequent |

Less frequent |

|

Unknown |

|

Iron deficiency |

Hemorrhage, hemolysis |

|

No cause could be found in around 30% of cases |

|

Inflammation/infection |

Hyperparathyroidism |

|

|

|

|

Vit. B 12, folate deficiency |

|

|

|

|

Bone marrow suppression |

|

|

|

|

Pure red cell aplasia |

|

|

|

|

Aluminum toxicity |

|

|

|

Inadequate dialysis |

|

|

|

|

|

Carnitine deficiency |

|

|

|

|

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

|

|

|

|

ESA subcutaneous administration with obesity |

|

||

|

|

|||

Table 1: Summary of causes of ESA Hyporesponsiveness.

- Iron Deficiency

Iron deficiency is the most common cause of ESA hyporesponsiveness [14] and it may be absolute or functional type, which is more common. The absolute type is characterized by severely deficient or lacking iron storage, essentially due to blood loss. Usually, Transferrin Saturation (TSAT)% is less than or equal to 20% with serum ferritin less than 200 ng/mL. The functional type has normal iron storage with reduced iron availability for erythropoiesis. It is associated with low TSAT % and normal/high ferritin levels. Functional iron deficiency is further divided into 2 subtypes: the first is attributed to ESA therapy itself, and the second is related to anemia of chronic disease.

Measurement of red blood cells Hb content could be better for the assessment of functional iron deficiency and possible response to iron therapy. This can be achieved through the measurement of hypochromic red blood cell (HRCs) percentage with threshold value more than 6%, and reticulocyte Hb content (CHr) with threshold value less than 29 pg., according to NICE guidelines, 2016 [15]. The HRCs % and CHr are more widely used in Europe than in the United States practice. In cases with ESA-induced iron deficiency, the response can occur to IV iron administration and concurrent increase of ESA dose together leading to decrease of ferritin levels. Conversely, in anemia of chronic disease, IV iron administration will not improve erythropoiesis and will be associated with a progressive increase in ferritin levels [16].

- Inflammation

Chronic inflammatory status is common in hemodialysis patients and is considered a major cause of ESA hyporesponsiveness. Inhibition of production leads to hypoproliferative anemia of chronic disease. Underlying causes of chronic inflammation include dialysis catheter-related infection, infected or nonfunctioning arteriovenous graft, failed renal allograft, or uremic toxins. Other causes include malignancies, chronic infections, autoimmune disorders, or periodontal disease. Systemic inflammation affecting the immune system function can be a sequence of gut microbiota dysbiosis. IL-6 works in the opposite direction of EPO regarding its effect on bone marrow proliferation. Serum levels of both IL-6 and TNF-alpha are directly proportional to ESA dose in hemodialysis patients [17-19].

- Inadequate Dialysis

Uremic toxins can cause ESA hyporesponsiveness through nonselective bone marrow suppression or through selective suppression of erythroid colony-forming units. Accumulation of quinolinic acid in uremic patients leads to inhibition of EPO gene expression, possibly mediated by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF)1 alfa. Other substances like Indoxyl Sulfate (IS) and indoxyl glucuronide can suppress transcriptional HIF-1 alfa activity leading to inappropriate EPO production. Dialysis dose should be monitored in malfunctioning dialysis catheters and in fistula with lower blood flow rates. The chronic inflammatory state can occur in hemodialysis patients due to low-level endotoxin and microbial contamination of dialysis water. This was confirmed through the beneficial effect of using ultrapure water. According to large randomized clinical trials, the use of high-flux and online treatments, though supposed better removal of large and middle molecules, was not associated with a significant effect on anemia and ESA requirements. With high predialysis hematocrit values or slow blood flow of vascular access, RBCs damage can occur due to shear stress and high pressure in dialyzer capillaries.

It was suggested that the use of mixed pre- and postdilution Hemodiafiltration (HDF) might be preferred to postdilution HDF through avoidance of progressive hemoconcentration. However, this hypothesis needs more confirmation. There is no clear evidence supporting the beneficial effect of increasing dialysis frequency per se regarding response to ESA therapy [20-22]. Trials to improve dialysis quality have led to the development of a novel class of dialysis membranes; called Medium Cut-Off (MCO) with Molecular Weight Cut-Off (MWCO) close to MW of albumin and very High Retention Onset (HRO) [23]. Recently, these membranes are called HRO membranes. They are made of polyarylethersulfone/polyvinylpyrrolidone with a mean pore radius of 5 nm, in between high-flux and High Cut-Off (HCO) membranes. They are designed to enhance the clearance of molecules larger than B2-microglobulin with the ability of albumin retention. In addition, the internal diameters of the fibers are reduced to increase blood compartment resistance and enhance dialyzer internal filtration and back-filtration. The resulting convection is comparable to that of classical high flux membranes, with effective removal of middle and large molecules without need for fluid substitution. Using this novel class of dialyzers, HRO is called Expanded Hemodialysis (EHDx).

EHDx has favorable response to ESA therapy in comparison with the use of a High-Flux (HF) dialyzer. That effect was attributed to the superior removal of inflammatory cytokines with better iron metabolism in a hepcidin- independent mechanism. More middle-molecule uremic toxins clearance with more reduction of TNF-alfa was achieved with the use of MCO dialyzers than with HF dialyzers. Moreover, high-flux dialysis did not show superiority to low-flux dialysis in improving ESA hyporesponsiveness [24]. In a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis study, it was concluded that EHDx showed safety regarding albumin loss in dialysate and back-filtration of endotoxins. Additionally, EHDx proved effective clearance of middle and large uremic toxin molecules in comparison with high-flux hemodialysis and online HDF with potential anti-inflammatory activity [25,26].

- Aluminum Toxicity

Although rarely encountered nowadays, aluminum intoxication could be seen with high content in the dialysis water source or with technical issues related to its treatment system [27,28]. The resulting anemia is of microcytic hypochromic or normochromic type, which reflects ESA hyporesponsiveness associated with affected enzymes required for heme synthesis. Management requires incremental dosing of desferrioxamine infusion during hemodialysis sessions to avoid irreversible neurological damage. Other sources of aluminum exposure are aluminum-containing phosphate binders and antacids. Combined use of sodium citrate with aluminum-containing phosphate binders enhances aluminum intoxication, through increment of intestinal absorption. A concern was raised with intake of ferric citrate as a phosphate binder due to the possible increase of aluminum absorption from food, water drinking, and concurrent medication use. Additional medications considered sources of aluminum are iron and calcium-containing medications, calcitriol vitamin B complex, acetylsalicylic acid, clonidine, calcium carbonate, and iron sulfate. Injectable medications including iron, erythropoietin, and insulin have been found markedly more aluminum contaminated than oral formulations.

Abnormal serum aluminum levels are those exceeding 20 mcg/L. Based on Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guidelines, serum aluminum levels should be tested at least annually in hemodialysis patients and every 3 months in those who are taking aluminum-containing medications. The Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) recommendation is to perform periodic chemical monitoring for dialysis water at least annually and more frequently when indicated. The maximum allowed aluminum concentration is 0.01 mg/L [29-32].

- Malnutrition

Protein-energy wasting, and inflammation are closely related. Malnutrition- inflammation complex is considered a predisposing factor for impaired response to ESA therapy [33]. Additionally, vitamin deficiencies can be considered a contributing factor. Folic acid is involved in erythroid proliferation. Vitamin C, with its antioxidative effect, downregulates cytokine synthesis and increases iron utilization. Copper increases iron absorption. Alpha-lipoic acid is needed for ATP synthesis, and it has a lowering effect on symmetric-dimethyl arginine, reducing oxidative stress. l- Carnitine has an antioxidative stress effect by stimulating heme-oxygenase 1. There is no available data to support a relation between vitamin 6 and ESA hyporesponsiveness [34-37].

- Pure Red Cell Aplasia (PRCA)

As a consequence of epoetin-induced polyclonal antibodies, neutralization of exogenous ESA and cross-reaction with endogenous EPO occur [38]. Hence, erythropoiesis becomes defective with undetectable EPO levels in serum. The resulting rare condition is called Pure Red Cell Aplasia (PRCA). It is manifested by a rapid drop of Hb and undetectable reticulocytes associated with normal counts of white blood cells and platelets. PRCA is suspected with a monthly decrease of Hb level by 2 gm/dl or more r if reticulocyte count is less than 20,000/microL. It is usually suspected when hyporesponsiveness is preceded by a reasonable response to ESA therapy. For PRCA to occur, at least 3–4 weeks of EPO therapy must be there, with the typical presentation following 6–18 months of intake [39]. According to Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 012 guidelines, screening for PRCA due to anti-EPO antibodies in patients on EPO therapy for at least 4 weeks was recommended with absolute reticulocyte count less than 10,000/microL, normal platelet and white blood cell count, in addition, to drop of Hb level more than 0.5–1.0 g/dl weekly or need for 1–2 transfusions per week [40]. All PRCA cases induced by anti-EPO antibodies were reported after subcutaneous ESA administration, with a treatment duration ranging from 1 month to 5 years [41]. PRCA mandates blood transfusion and immunosuppression, sometimes with rituximab [42]. Following the disappearance of EPO antibodies, IV ESA administration can be restarted with monitoring of anti-EPO antibody titers and Hb levels. Renal transplantation is the definitive treatment.

- Other causes

- CKD-mineral bone disease interrelation between vitamin D, hyperparathyroidism, and disturbed response to ESA therapy is well known [43]. Vitamin D deficiency has a negative impact on Higher levels of parathyroid hormone inhibit erythroid progenitors and reduce red cell survival. Hyperphosphatemia leads to the downregulation of erythropoietin receptors. Hyperparathyroidism can be complicated by bone marrow fibrosis [44]. Higher levels of fibroblast growth factor-23 and alkaline phosphatase are associated biomarkers of ESA hyporesponssiveness [45].

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers: they inhibit angiotensin-II-induced EPO production and promote N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline leading to prevention of recruitment of pluripotent stem cells; among other mechanisms [46].

- Bone marrow disorders: either primary or due to myelosuppressive

- Malignancies: especially of hematological origin, e.g. multiple myeloma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia [47].

- Hypothyroidism: higher TSH levels are related to decreased responsiveness to ESA therapy [48].

- Hypogonadism: there is association between lower testosterone levels and decreased response to ESA therapy [49].

- Hypomagnesemia: magnesium deficiency can increase oxidative stress and lead to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alfa and IL-1B), reducing ESA responsiveness. Serum magnesium levels were correlated with high ERI [50].

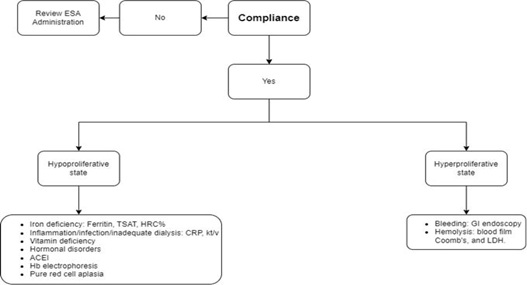

Suggested Stepwise Approach To ESA Hyporesponsiveness

- Step One: Exclude noncompliance to ESA therapy, especially in subcutaneous self-administration patients and those with financial issues.

- Step Two: Evaluate the proliferative status through estimation of reticulocyte count: Hyperproliferative states: we search for possible gastrointestinal bleeding using endoscopy or the possibility of hemolysis with testing of blood film, bilirubin, LDH, and Coombs test.

- Step Three: Hypoproliferative state: We proceed for iron profile study: Ferritin, TSAT, and HRC % to exclude functional and absolute iron deficiency.

- Step Four: Hypoproliferative state; Exclusion of infection, inflammation, and inadequate dialysis: evaluation of kt/v CRP, in addition to a physical examination to exclude thrombosed arteriovenous graft, occult infection, failed kidney allograft, and infected dialysis access.

- Step Five: Hypoproliferative state; Exclusion of vitamin deficiencies; Hb electrophoresis if indicated. Discontinuation of medications affecting bone marrow erythropoiesis.

- Step Six: Hypoproliferative state, Exclusion of hyperparathyroidism.

- Step Seven: Undetectable reticulocytic count: Consideration of PRCA (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Suggested stepwise approach to ESA Hyporesponsiveness. TSAT: transferrin saturation, HRC%: hypochromic red blood cell %, CRP: C-reactive protein, GI: gastrointestinal, ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and LDH: lactate dehydrogenase.

Clinical outcomes

Hyporesponsiveness to ESA therapy has been found to be associated with higher mortality in several trials [51]. This was shown through one observational study of dialysis patients with Hb levels less than 9.5 gm/dl during larger ESA dose changes over 11 months period. The increased mortality has been in the initial period of therapy as shown in Trial to Reduce Cardiovascular Events with Aranesp Therapy (TREAT) study [52]. Both the underlying cause of ESA hyporesponsiveness and the ESA dose itself contributes to increased mortality, with the former having more significance [53]. ESA hyporesponsiveness has been associated with the development of insulin resistance [54]. Impaired response to ESA therapy can contribute through an unknown mechanism, in more rapid progression to end-stage renal disease. This was suggested by a study of 194 consecutive CKD patients on ESA therapy between 2002 and 2006 [55].

Potential and investigational agents

Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitors (HIF-PHIs)

Also, they are called HIF stabilizers. The major transcription factor for the EPO gene, HIF, was discovered in 1992. This was followed by the creation of HIF stabilizers. Their action process is via the HIF-prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) pathway through stimulation of transcription of EPO gene resulting in increased endogenous EPO levels. Anemia-induced tissue hypoxia leads to stimulation of HIF system. Intranuclear dislocation of HIF- alpha is followed by its binding to HIF-B to form a functional dimer that binds to hypoxia-response elements on DNA. Subsequently, HIF induces the expression of genes regulating erythropoiesis and iron metabolism in a wide range of tissues. HIF activity and degradation are regulated by PHD proteins. They are oxygen-sensitive hydroxylase enzymes. Their activity is reduced during conditions of hypoxia. Development of CKD leads to HIF dysregulation with reduced EPO production. HIF-PHIs enhance the physiologic response to hypoxia through suppression of PHD resulting in endogenous EPO production with Hb overshoots less than ESA therapy. HIF-PHIs have direct and indirect beneficial effects on iron deficiency, either absolute or functional type. Directly, HIF-PHIs regulate iron homeostasis proteins, for example, duodenal cytochrome B, ferroportin, transferrin, and divalent metal-ion transporter 1. Indirectly, HIF-PHIs have suppressive action on hepcidin (via erythroferrone, the main hepcidin- erythroid regulator), resulting in a possible increase in iron availability [56,57]. Agents of this novel class included in clinical trials are: daprodustat, vadadustat, and raxadustat; all are used through oral administration.

The safety and efficacy of the HIF PHI daprodustat were evaluated in a trial of 2964 patients on dialysis over 2.5 years (average hemoglobin 10.4 g/L) who were randomly given daprodustat (dose range from 4 to 24 mg daily, according to ESA dose) or injectable ESA (epoetin alfa for hemodialysis patients or darbepoetin alfa for peritoneal dialysis patients). The average change in Hb concentration was 0.28 g/dL with daprodustat therapy and 0.10 g/dL with ESA therapy. Rates of adverse cardiovascular events, a composite of death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and stroke, were similar between the treatment groups (25.2 versus 26.7% for daprodustat and epoetin alfa, respectively), as were the rates of other adverse events. The efficacy of another dosing of daprodustat was studied in a 52-week trial in which 407 patients on hemodialysis were randomly assigned to daprodustat (dose range from 2 to 48 mg) thrice weekly with dialysis or to epoetin alfa; the average change in Hb concentration and rates of adverse events were comparable between the treatment groups.

The efficacy and safety of vadadustat have been studied in comparison with Darbepoetin alfa in hemodialysis patients in a trial of 3554 patients who were randomly assigned to receive vadadustat 150–600 mg or darbepoetin alfa. to target Hb of 10 to 11 g/dL in patients of the United States and 10 to 12 g/dL in patients from other countries. Iron was given to all participants Targeting Transferrin Saturation (TSAT) >20 percent and serum ferritin>100 ng/mL. Between weeks 40 and 52, prevalent dialysis patients assigned to vadadustat were less likely to maintain target Hb (44 versus 51 percent), although rates of red cell transfusion were similar (2.0 vs. 1.9% of prevalent dialysis patients). Findings from a similar trial of 369 patients on dialysis showed comparable results.

Collectively, data of patients from both trials, rates of mortality (13.0 vs. 12.9%, nonfatal stroke (1.3 vs. 1.9%), hospitalization for heart failure (3.9 vs. 4.0%), and nonfatal myocardial infarction (3.9 vs. 4.5%) were comparable. Other adverse events, including hypertension, diarrhea, and pneumonia, were lower in the vadadustat group; both among prevalent (55 vs. 58%) and incident (50 vs. 57%) dialysis patients [58,59]. Comparable findings have been obtained from smaller studies of roxadustat in comparison with findings of studies of daprodustat and vadadustat [60]. As roxadustat had a selective activity ligand for thyroid hormone receptor B; with its similar structure to T3, it can suppress TSH release. These agents have gained approval for clinical use in Europe, China, Japan, and Chile but not yet in the United States. Long-term follow-up is required for concerns like increased risk of cancer, cardiovascular events, thrombosis, and deterioration of diabetic retinopathy in addition to others [61-63].

Experimental Combination of ESA and Thrombopoietin

The use of ESA and thrombopoietin in combination to treat EPO-resistant anemia in otherwise healthy rats was suggested considering the concept of the ability of thrombopoietin to stimulate self-renewal of stem cells and correct depletion of erythroid precursor cells [64].

L-Carnitine

Dialysis patients are in a state of chronic carnitine deficiency, associated with disturbance of fatty acid and other organic acid metabolism. Observational studies showed association between elevated ERI and low l- carnitine. However, other studies did not show evidence of beneficial effects of carnitine regarding oxidative stress and inflammation in hemodialysis patients [65].

Pentoxifylline

It has anti-inflammatory effects through inhibition of the production of TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma. This was illustrated with oral pentoxifylline given to dialysis patients hyporesponsive to ESA therapy with a resulting significant improvement of Hb levels in a small open-label study. However, CRP levels were not changed. Further studies did not support the clinical benefit of pentoxifylline in anemic dialysis patients [66].

AST-120

It is an inert binding compound with an antioxidant effect and capability to reduce uremic toxins, indoxyl sulfate, and p-cresyl sulfate levels as well. Some improvement of anemia was demonstrated in a crossover study with AST-120 given to predialysis patients [67].

Vitamin E-Coated Dialyzer

There is controversy regarding its effects on oxidative stress, inflammation, and ESA responsiveness. However, direct association was suggested between the higher positive effect of vitamin E-coated dialyzer and higher levels of ERI [68].

Anti-Hepcidin Agents

Lexaptepid pegol and human anti-BMP6 antibodies are hepcidin- suppressing agents. Experimental use of anti-BMP6 antibodies reduced the need for EPO in the treatment of anemia of chronic disease. Other agents targeting the ferroportin degradation action of hepcidin are for current research [69].

Alpha-Lipoic Acid

In a multicenter prospective randomized study, it was shown that alpha- lipoic acid in a dose of 600 mg/day had anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects leading to improvement of anemia and EPO hyporesponsiveness in diabetic patients on hemodialysis. Further studies are required for better evaluation with the use of different doses [70].

Statin Therapy

In a meta-analysis study, it was found that CKD patients treated with a statin had a trend of increased Hb and decreased ferritin levels. Further studies are required for more result confirmation [71].

SGLT2 Inhibitors

They have been shown to have a beneficial effect on anemia improvement through decreasing hepcidin and ferritin and increasing transferrin [72].

Lactoferrin (Bovine Milk Derivative Lactoferrin, BMLF)

It is natural iron -containing glycoprotein with immunomodulatory and anti- inflammatory actions with lowering of IL-6 serum levels.IL-6 has increasing effects of serum hepcidin. Based on this, BMLF has a potential effect to inhibit hepcidin secretion and consequently leading to ferroportin upregulation with better iron utilization. So, it has the potential beneficial effect through correction of anaemia caused by inflammation and iron deficiency. Possibility of oral administration is an advantage. This was proved by RCT of Ahemed &Abdel Aal,2023 with the oral use of 100 mg of 20-30% iron saturated BMLF equivalent to 70-84 microgram of elemental iron twice daily for six months for patients on hemodialysis in comparison with oral use of 576 of ferrous glycine sulfate equivalent to 100 mg elemental iron; twice daily for the same duration. Patients with BMLF achieved the Hb target of average of 9.7 gm/dl compared with patients on ferrous glycine; of Hb target 8.1 gm/dl. BMLF was found to be an effective agent for management of anemia in patients on hemodialysis due to antiinflammatory hepcidin-suppression action. In other words, through better iron utilization not merely iron supplementation [73-75].

Conclusion

Improper response to ESA therapy has well-known negative outcomes in hemodialysis patients. A wise approach is to target the underlying causes before the up-titration of the ESA dose. The discovery of new areas of hepcidin and HIF pathway found the way for the possible development of novel therapeutic agents, including EPO gene therapy, hepcidin antagonists, and better-planned tackling HIF stabilizers. Research work is ongoing for better understanding the problem of ESA hyporesponsiveness and detection of possible solution. More dedicated efforts are still required for better-planned tackling of a problem that has continued for more than two decades with more expected future success.

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding sources

There was no external funding for this work.

References

- Cappellini MD, Motta I (2015) Anemia in clinical practice-definition and classification: Does hemoglobin change with aging?. Seminars in Hematol 52: 261-269.

- Locatelli F, Pisoni RL, Combe C, Bommer J, Andreucci VE, et al. (2004) Anaemia in haemodialysis patients of five European countries: Association with morbidity and mortality in the Dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (DOPPS). Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 121-132.

- Taddei S, Nami R, Bruno RM, Quatrini I, Nuti R (2011) Hypertension left ventricular hypertrophy and chronic kidney disease. Heart Fail Rev 16: 615-620.

- Babitt JL, Lin HY (2012) Mechanisms of anemia in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1631-1634.

- Bahlmann FH, Kielstein JT, Haller H, Fliser D (2007) Erythropoietin and progression of CKD. Kidney Int 107: S21- S25.

- Batchelor EK, Kapitsinou P, Pergola PE, Kovesdy CP, Jalal DI (2020) Iron deficiency in chronic kidney disease: Updates on pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 456-468.

- Eschbach JW, Abdulhadi MH, Browne JK, Delano BG, Downing MR, et al. (1989) Recombinant human erythropoietin in anemic patients with end-stage renal disease. Results of a phase III multicenter clinical trial. Ann Int Med 111: 992.

- Luo J, Jensen DE, Maroni BJ, Brunelli SM (2016) Spectrum and burden erythropoiesis-stimulating agent hyporesponsiveness among contemporary hemodialysis patients. Am Kidney Dis 86: 763.

- Sibbel SP, Koro CE, Brunelli SM, Cobitz AR (2015) Characterization of chronic and acute ESA hyporesponse: A retrospective cohort study of hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrology 16: 144.

- Locatelli F, Aljama P, Bárány P, Canaud B, Carrera F, et al. (2004) Revised European best practice guidelines for the management of anaemia in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 1-47.

- Chapter 1: Diagnosis and evaluation of anemia in CKD (2011) Kidney International Supplements 2: 288-291.

- Chait Y, Kalim S, Horowitz J, Hollot CV, Ankers ED, et al. (2016) The greatly misunderstood erythropoietin resistance index and the case for a new responsiveness measure. Hemodial Int 20: 392-398.

- Gilbertson DT, Peng Y, Arneson TJ, Dunning S, Collins AJ (2013) Comparison of methodologies to define hemodialysis patients hypo-responsive to epoetin and impact on counts and characteristics. BMC Nephrology 20: 14-44.

- Drueke T (2001) Hyporesponsiveness to recombinant human erythropoietin. Nephrol DialTransplant 16: 725-728.

- Laura E, Thomas W, Glen J, Padhi S, Pordes BA, et al. (2016) Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency in CKD: A summary of the NICE guideline recommendations and their rationale. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 67: 548-558.

- Madu AJ, Ughansoro MD (2017) Anemia of chronic disease: An in-depth review. Medical Principles and Practice 26: 1-9.

- Goicoechea M, Martin J, de Sequera P, Quiroga JA, Ortiz A, et al. (1998) Role of cytokines in the response to erythropoietin in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 54: 1337.

- Nassar GM, Fishbane S, Ayus JC (2002) Occult infection of old nonfunctioning arteriovenous grafts: A novel cause of erythropoietin resistance and chronic inflammation in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int Suppl 80: 49-54.

- Solid CA, Foley RN, Gill JS, Gilbertson DT, Collins AJ (2007)Epoetin use and kidney disease outcomes quality initiative hemoglobin targets in patients returning to dialysis with failed renal transplants. Kidney Int 71: 425-430.

- Movilli E, Cancarini GC, Zani R, Camerini C, Sandrini M, et al. (2001) Adequacy of dialysis reduces the doses of recombinant erythropoietin independently from the use of biocompatible membranes in haemodialysis patients. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 16:111-114.

- Locatelli F, Del Vecchio L (2003) Dialysis adequacy and response to erythropoietic agents: What is the evidence base?. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 29-35.

- Hsu PY, Lin CL, Yu CC, Chien CC, Hsiau TG, et al. (2004) Ultrapure dialysate improves iron utilization and erythropoietin response in chronic hemodialysis patients—A prospective cross-over study. J of Nephrol 17: 693.

- Yang J, Ke G, Liao Y, Guo Y, Gao X, et al. (2002) Efficacy of medium cut-off dialyzer and comparison with high-flux dialyzers in patients on maintenance hemodialysis: A systematic review and q meta-analysis. Therapeutic Apheresis and Dial 26: 756-768.

- Yaqoob MM, Ahmad R, Shivakumar KA, Sallomi DF, Fahal IH, et al. Resistance to recombinant human erythropoietin due to aluminium overload and its removal by low dose desferrioxamine therapy. Postgrad Med J 69: 124.

- Bohrer D, Bertagnolli DC, de Oliveira SM, do Nascimento PC, de Carvalho LM, et al. (2009) Role of medication in the level of aluminium in the blood of chronic hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1277-1281.

- Zhao Y, Gan L, Niu Q, Ni M, Zuo L (2022) Efficacy and safety of expanded hemodialysis patients: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Renal Fail 44: 541-550.

- Zhang Z, Yang T, Li Y, Li Y, Li J, et al. (2022) Effects of expanded hemodialysis with medium cut-off membranes on maintenance hemodialysis patients: A review. Membranes 12: 253.

- Jofre R, Rodriguez-Benitez P, López-Gómez JM, Pérez-Garcia R (2006) Inflammatory syndrome in patients on hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: S274-S280.

- Bamonti-Catena F, Buccianti G, Porcella A, Valenti G, Como G, et al. (1999) Folate measurement in patients on regular hemodialysis treatment. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 33: 492-497.

- Bridges KR, Hoffman KE (1986) The effects of ascorbic acid on the intracellular metabolism of iron and ferritin. J Biol Chem 261: 14273-14277.

- Tan BL, Norhaizan ME, Liew WP (2018) Nutrients and oxidative stress: Friend or foe?. Oxid Med Cell Longev 31: 719584.

- Froment DP, Molitoris BA, Buddington B, Miller N, Alfrey AC, et al. (1989) Site and mechanism of enhanced gastrointestinal absorption of aluminum by citrate. Kidney International 36: 978-984.

- Van Buren PN, Lewis JB, Dwyer JP, Greene T, Middleton J, et al. (2015) The phosphate binder ferric citrate and mineral metabolism and inflammatory markers in maintenance Dialysis patients: Results from Prespecified analyses of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 479-488.

- Gupta A (2014) Ferric citrate hydrate as a phosphate binder and risk of aluminum toxicity. Pharmaceuticals 7: 990.

- Bohrer D, Bertagnolli DC, de Oliveira SM, do Nascimento PC, de Carvalho LM, et al. (2007) Drugs as a hidden source of aluminium for chronic renal patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 605-611.

- AAMI (2013) Association for the Advancement of Medical instrumentationStandards, Dialysis.

- Calo LA, Davis PA, Pagnin E, Naso A, Piccoli A, et al. (2008) Carnitine-mediated improved response to erythropoietin involves induction of heme oxygenase-1: Studies in humans and in animal model. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 890-895.

- Casadevall N, Nataf J, Viron B, Kolta A, Kiladjian JJ, et al. (2002) Pure red-cell aplasia and antierythropoietin antibodies in patients treated with recombinant erythropoietin. N Engl J Med 346: 469-475.

- Rossert J, Casadevall N, Eckardt KU (2004) Anti-erythropoietin antibodies and pure red cell aplasia. Journal of American Society Nephrology 15:398-406.

- Quint L, Casadevall N, Giraudiet S (2004) Pure red cell aplasia in patients with refractory anemia treated with two different recombinant erythropoietins. Br J Haematol 124: 842.

- Verhelst D (2004) Treatment of erythropoietin -induced pure red cell aplasia: A retrospective study. Lancet 363: 1768.

- Bamgbola OF (2011) Pattern of resistance to erythropoietin-stimulating agents in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 80: 464-474.

- Del Vecchio L, Pozzoni P, Pozzoni P, Locatelli F (2005) Inflammation and resistance to treatment with recombinant human erythropoiesis. J Ren Nutri 15: 137-141.

- Usui T, Zhao J, Fuller DS, Hanafusa N, Hasegawa T, et al. (2021) Association of erythropoietin resistance and fibroblast growth factor 23 in dialysis patients: Results from the Japanese dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study. Nephrology 26: 46-53.

- Aiz M, Rousseau A, Guyene TT, Michelet S, Grognet JM, et al. (1996) Acute angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition increases the plasma levels of the natural stem cell regulator N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline. J Clin Invest 97: 839-844.

- Latcha S (2019) Anemia management in cancer patients with chronic kidney disease. Seminars in Dialysis 23: 513-519.

- Saleh F, Naji MN, Eltayeb AA, Hejaili FF, Al Sayyari AA (2018) Effect of thyroid function status in hemodialysis patients on erythropoietin resistance and interdialytic weight gain. Kidney Diseases Transplantation 29: 1274-1279.

- Stenvinkel P, Barany P (2012) Hypogonadism in males with chronic kidney disease: another cause of resistance to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents?. Contrib Nephrol 178: 35-39.

- Yu L, Song J, Song J, Zu Y, Li H, et al. (2019) Association between serum magnesium and erythropoietin responsiveness in hemodialysis patients: A cross- sectional study. Kidney Blood Press Res 44: 354-361.

- Bradbury BD, Danese MD, Gleeson M, Critchlow CW (2009) Effect of epoetin alfa dose changes on hemoglobin and mortality in hemodialysis patients with hemoglobin levels persistently below 11 gldL. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 630-637.

- Solomon SD, Uno H, Lewis EF, Eckardt KU, Lin J et al. (2010) Erythropoietic response and outcomes in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 363: 1146-1155.

- Szczech LA, Barnhart HX, Inrig JK, Reddan DN, Sapp S, et al. (2008) Secondary analysis of the CHOIR trial epoetin alfa dose and achieved hemoglobin outcomes. Kidney Int 74: 791-798.

- Abe M, Okada K, Soma M, Matsumoto K (2011) Relationship between insulin resistance and epoetin response in hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 75: 49-58.

- Minutolo R, Conte G, Cianciaruso B, Bellizzi V, Camocardi A, et al. (2012) Hyporesponsiveness to erythropoiesis stimulating agents and renal survival in non-dialysis CKD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 2880-2886.

- Nair S, Trivedi M (2020) Anemia management in dialysis patients: A PIVOT and a new path? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 29: 351-355.

- Rosenberger C, Mandriota S, Jürgensen JS, Wiesener MS, Wiesener MS, et al. (2002) Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alfa and 2 alfa in hypoxic and ischemic rat kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1721-1732.

- Singh AK, Carroll K, Perkovic V, Solomon S, Jha V, et al. (2021) Daprodustat for the treatment of anemia in patients undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med 385: 2325-2335.

- Echardt KU, Agarwal R, Aswad A, Aswad A, Block GA, et al. (2021) Safety and efficacy of Vadadustat for anemia in patients undergoing dialysis. New Engl J Med 384: 1601-1612.

- Liu Z, Zhang A, Hayden JC, Bhagavathula AS, Alshehhi F, et al. (2020) Roxadustat (FG-4592) treatment for anemia in dialysis-dependent (DD) and not dialysis-dependent (NDD) chronic kidney disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol Res 155: 104747.

- Tokuyama A, Kadoya H, Obata A, Obata T, Sasaki T, et al. (2021) Roxadustat and thyroid stimulating hormone suppression. Clin Kidney J 14: 1472-1474.

- Yap DY, McMahon LP, Hao CM, Hu N, Okada H, et al. (2021) Recommendation by the Asian pacific society of nephrology 9APSN on the appropriate use of HIF-PH inhibitors. Nephrology(carlton) 26: 105-118.

- Sanghani NS, Haase VH (2019) Hypoxia-inducible factor activators in renal anemia : Current clinical experience. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 26: 253-266.

- Kular D, Macdougall I (2019) HIF stabilizers in the management of renal anemia: From bench to bedside to pediatrics. Pediatr Nephrol 34: 365-378.

- Zou H, Xu P, Wong RSM, Yan X (2022) A novel combination therapy of epoetin and thrombopoietin to treat epoetin-resistant anemia. Pharm Res 39: 1249-1268.

- Yang SK, Xiao L, Song PA, Xu X, Liu FY, et al. (2014) Effect of L-carnitine therapy on patients in maintenance hemodialysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nephrol 27: 317-329.

- Johnson DW, Pascoe EM, Badve SV, Dalziel K, Cass A, et al. (2015) A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of pentoxifylline on erythropoiesis- stimulating agent hypo-responsiveness in anemic patients with CKD: The handling erythropoietin resistance with Oxpentifylline (HERO) trial. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 49-57.

- Wu IW, Hsu KH, Sun CY, Tsai CJ, Wu MS, et al. (2014) Oral adsorbent AST-120 potentiates the effect of erythropoietin- stimulating agents on stage 5 chronic kidney disease patients: A randomizes crossover study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29: 1719-1727.

- Panichi V, Rosati A, Paoletti S, Ferrandello P, Migliori M, et al. (2011) A vitamin E-coated polysulfone membrane reduces serum levels of inflammatorymarkers and resistance to erythropoietin-stimulating agents in hemodialysis patients: Results of a randomized cross-over multicenter Blood Purif 32: 7-14.

- Malyszko J, Malyszko JS, Matuszkiewics-Rowinska J (2019) Hepcidin as a therapeutic target for anemia and inflammation associated with chronic kidney disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets 23: 407-421.

- Abdel Hamid DZ, Nienaa YA, Nienaa YA (2022) Alpha-lipoic acid improved anemia, erythropoietin resistance, maintained glycemic control, andreduced cardiovascular risk in diabetic patients on hemodialysis: A multicenter prospective randomized controlled study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 26: 2313-2329.

- Tsai MH, Su FY, Chang HY, Su PC, Chiu LY, et al. (2022) The effect of statin on Anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage kidney disease: Asystematic review and Meta-analysis. J Pers Med 12:1175

- Schmidt DW, Argyropoulos C, Sing N (2021) Are the protective effects of SGLT2 inhibitors a ‘class effect’ or are there differences between agents?. Kidney 360 2: 881-885.

- Rosa L, Cutone A, Lepanto MS, Paesano R, Valenti P (2017) Lactoferrin: A natural glycoprotein involved in iron and inflammatory homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci 18: 1985.

- Bonaccorsi di Patti MC, Cutone A, Polticelli F, Luigi Rosa, Mariastefania Lepanto, et al. (2018) The ferroportin-ceruloplasmin system and the mammalian iron homeostasis machine: Regulatory pathways and the role of lactoferrin. Biometals 31: 399-414.

- Mahmoud RMA, Mohammed A (2023) Lactoferrin: A Promising New Player in Treatment of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Patients on Regular Hemodialysis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 34: 235-241.

Citation: Ahmed Yasin (2024) Hyporesponsiveness to Erythropoietin- Stimulating Agents: Targets of Management. J Nephrol Renal Ther 10: 089.

Copyright: © 2024 Ahmed Yasin MD, FASN, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.