Journal of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery Category: Clinical

Type: Case Report

Incidental Finding of Lingual Thyroid in an Infant with Hoarseness

*Corresponding Author(s):

Pamela MuddGeorge Washington University School Of Medicine And Health Sciences, Washington, D.C., United States

Tel:+1 2024764852,

Email:pmudd@childrensnational.org

Received Date: Jul 04, 2019

Accepted Date: Jul 18, 2019

Published Date: Jul 25, 2019

Abstract

Failure of the thyroid to descend from the base of tongue to the neck during embryogenesis can lead to an ectopic lingual thyroid. This is a rare anomaly that most commonly presents with dysphagia or dysphonia, although lingual thyroid can be asymptomatic with a variable presentation. A 6-month-old female infant presented to the Otolaryngology clinic with hoarse voice. She had a history significant for congenital hypothyroidism detected on newborn screening and treated with thyroid hormone replacement. Upon gross examination of the oral cavity, no abnormality or mass was observed. On laryngeal endoscopy she was noted to have a left vocal cord cyst and a secondary reactive nodule on the right vocal cord. Additionally, a well-circumscribed mass at the base of the tongue was identified. Based on her clinical history, in addition to a prior neck ultrasound demonstrating absence of thyroid tissue in the neck, a diagnosis of ectopic lingual thyroid was made. At 6 month follow-up, she had spontaneous resolution of her hoarseness and vocal cord cyst, with persistent ectopic lingual thyroid not visible on direct oral exam or seen on neck ultrasound. No Technetium scan (Tc-99) was performed at this time due to the need to stop congenital hypothyroidism therapy for imaging and concerns over the neurological consequences this posed to the infant. Asymptomatic ectopic lingual thyroid imaging warranting congenital hypothyroid pediatric patients to be taken off of their established levothyroxine therapy should be considered with caution and we suggest, if possible, re-evaluating imaging once the patient has reached at least three years old, with appropriate follow-up care. This case highlights the variable presentation of thyroid location in congenital hypothyroidism and the importance of physician awareness of this potential diagnosis. Clinical suspicion for this rare embryologic anomaly must be shared across various pediatric specialties in order to ensure the identification of these patients. In cases of thyroid absence on ultrasound, an evaluation by an Otolaryngologist should be considered.

Keywords

Lingual Thyroid; dysphagia or dysphonia; Otolaryngology

INTRODUCTION

Thyroid ectopia refers to thyroid tissue located outside of its normal pretracheal position. The thyroid gland is the first endocrine gland during embryological development. It derives its fate from foregut endodermal cells of the pharyngeal floor, which go on to form the follicular cells that eventually will produce thyroid hormone within the gland. [1] The thyroid descends from the foramen cecum at the base of the tongue into the neck, passing anterior to the hyoid bone. During the migration a connection is maintained to the base of the tongue, known as the thyroglossal duct, which becomes fully obliterated by week seven of gestation when descent is completed. [2] Ectopic thyroid are described in the literature and may be found anywhere along this physiological migration pathway. In particular, thyroid tissue at the base of tongue, termed lingual thyroid, is the most common type of thyroid ectopia and accounts for 90% of all reported cases. Despite being the most common presentation, lingual thyroid remains a rare clinical entity with an incidence of 1 per 100,000 individual [3].

In 70% of cases the lingual thyroid is the only functional thyroid tissue, leading to the commonality of accompanying hypothyroidism in patients. [4] The mean age of diagnosis for lingual thyroid is 40 years old, with statistical peaks at 12.5 and 50 years, [5] with a strong female predominance. [6] With the implemented universal newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism lingual thyroid may be identified earlier in life for those who are symptomatic and present with dysphonia or dysphagia or potential respiratory distress likely to warrant further investigation beyond the diagnosis of congenital hypothyroidism. Challenges to diagnose lingual thyroid remain in infants who possess an asymptomatic course or present with associated symptoms only later in life. [6] Here, we describe the incidental finding of an asymptomatic lingual thyroid in an infant with hoarseness caused by a vocal cord cyst.

In 70% of cases the lingual thyroid is the only functional thyroid tissue, leading to the commonality of accompanying hypothyroidism in patients. [4] The mean age of diagnosis for lingual thyroid is 40 years old, with statistical peaks at 12.5 and 50 years, [5] with a strong female predominance. [6] With the implemented universal newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism lingual thyroid may be identified earlier in life for those who are symptomatic and present with dysphonia or dysphagia or potential respiratory distress likely to warrant further investigation beyond the diagnosis of congenital hypothyroidism. Challenges to diagnose lingual thyroid remain in infants who possess an asymptomatic course or present with associated symptoms only later in life. [6] Here, we describe the incidental finding of an asymptomatic lingual thyroid in an infant with hoarseness caused by a vocal cord cyst.

CASE REPORT

We present a case of a 6-month-old girl who was referred to the outpatient Otolaryngology clinic for hoarseness noted by her pediatrician. The mother reported the child had a normal cry on her first day of life, but shortly after, became constantly low and hoarse. Her past medical history was significant for congenital hypothyroidism detected on newborn screening, with a Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) of 70.9 μIU/ml (normal 0.5-5.0 μIU/ml). This had been managed with levothyroxine from 7 days of life. She was noted to be growing well and did not have any feeding or respiratory issues.

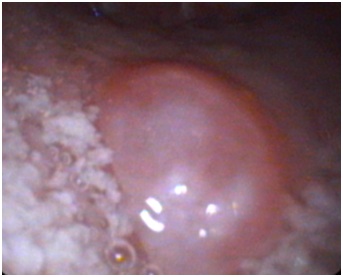

Upon gross examination of the oral cavity in the Otolaryngology clinic, no abnormality or mass was observed. On flexible laryngeal endoscopy she was noted to have a left vocal cord cyst and a secondary reactive nodule on the right vocal cord (Figure 1). The exam additionally revealed a smooth cystic appearing mass at the base of the tongue (Figure 2). Review of a prior neck ultrasound conducted by the pediatric Endocrinologist demonstrated the absence of thyroid tissue in the neck, in addition to her known hypothyroidism, lead to a diagnosis of lingual thyroid. At 6 month follow-up, the patient demonstrated spontaneous resolution of her hoarseness and vocal cord cyst, and continued asymptomatic presence of the lingual thyroid (Figure 3).

Upon gross examination of the oral cavity in the Otolaryngology clinic, no abnormality or mass was observed. On flexible laryngeal endoscopy she was noted to have a left vocal cord cyst and a secondary reactive nodule on the right vocal cord (Figure 1). The exam additionally revealed a smooth cystic appearing mass at the base of the tongue (Figure 2). Review of a prior neck ultrasound conducted by the pediatric Endocrinologist demonstrated the absence of thyroid tissue in the neck, in addition to her known hypothyroidism, lead to a diagnosis of lingual thyroid. At 6 month follow-up, the patient demonstrated spontaneous resolution of her hoarseness and vocal cord cyst, and continued asymptomatic presence of the lingual thyroid (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Left vocal cord cyst and a secondary reactive nodule on the right vocal cord.

Figure 1: Left vocal cord cyst and a secondary reactive nodule on the right vocal cord.

Figure 2: Well-circumscribed mass on posterior tongue as visualized in video laryngoscopy.

Figure 3: Six-month follow-up of resolved vocal cyst as visualized in video laryngoscopy.

Figure 3: Six-month follow-up of resolved vocal cyst as visualized in video laryngoscopy.Following the diagnosis of lingual thyroid, the patient was treated with continued levothyroxine therapy and monitored with coordinated care between general pediatrics, endocrinology, and otolaryngology.

DISCUSSION

The presentation of lingual thyroid is variable. Patients can present with dysphagia, voice changes, stridor or respiratory distress from oropharyngeal obstruction. More subtle presentations include chronic cough and obstructive sleep apnea. [7] Alternatively, it may remain asymptomatic into adulthood or be identified incidentally on imaging or physical exam, as in our case. It is estimated that about 70% of patients have accompanied hypothyroidism [8].

Interestingly, the patient’s lingual thyroid was found not to be causative of the hoarse voice, but rather that the vocal cord cyst was responsible for the vocal abnormality. This was determined upon six-month follow-up, in which the child’s voice abnormality and vocal cord cyst were both absent, despite the persistence of the lingual thyroid. Therefore, the lingual thyroid presentation was asymptomatic and the diagnosis was incidental.

The observed oral mass was diagnosed a lingual thyroid based on clinical history including the evaluation of a neck ultrasound, depicting the absence of a normal, pretracheal thyroid gland, and the clinical history of congenital hypothyroidism. The patient’s initial TSH level of 70.9 μIU/ml may have been suggestive of variable endogenous thyroid hormone production rather than an absent thyroid gland (athyreosis). Infants with athyreosis have a mean TSH of 255 μIU/ml, a level higher than those with ectopic thyroid. Yet variability does occur as TSH level can range from 67-701 μIU/ml for those with athyreosis, which can clinically blur the line between distinguishing infants with an ectopic thyroid or a true absent thyroid. [9] Further, at the time of diagnosis of congenital hypothyroidism the patient manifested overtreatment symptoms from the standard 50 mcg/day dose for full-term neonates and required reduction to 25 mcg/day. [10] Since two months of age the patient’s levothyroxine dosage was on the lower end of the guideline spectrum for hypothyroidism at 4 mcg/kg/day (normal 5-7 mcg/kg/day). [10] In retrospect, the patient’s clinical congenital hypothyroidism history and management plan was suggestive of trace hormone levels produced from an ectopic thyroid. Consultation with the pediatric Endocrinologist involved proved extremely valuable in determining whether further testing was warranted.

In other reported pediatric lingual thyroid cases, clinicians have performed a Technetium scan (Tc-99) to confirm that the lingual mass is representative of thyroid ectopic tissue, as differential diagnosis can include a thyroglossal duct cyst, dermoid cyst, vascular malformation, and valecular cyst. Here we present a case whereby the benefit of performing such imaging was not indicated. [11] Based on current literature it has been reported that thyroid gland uptake on Tc-99 imaging can be absent once levothyroxine therapy has been initiated.[12] Therefore, in order to properly image the patient, providers would have needed to discontinue the levothyroxine therapy for a period of time to induce her natural hypothyroid state to ensure accuracy of the scan. We deemed it was inappropriate to discontinue the patient’s levothyroxine supplementation given her young age and the well documented role of thyroid hormones impactful role on infant brain development within the literature. [13] While deeming that a Tc-99 scan was inappropriate at this time, the pediatric providers involved decided to revisit imaging in the future when the patient could safely be taken off of levothyroxine. We suggest considering Tc-99 imaging when patient’s reach three years of age, which has been demonstrated to be when brain development is less impacted by thyroid hormone levels. [14,15] The asymptomatic nature of the patient’s lingual thyroid also assisted the decision not to complete Tc-99 imaging at this time.

In addition, surgical intervention was deemed unnecessary, as the patient’s lingual thyroid remained asymptomatic, and medical management with levothyroxine therapy was continued. Surgical excision with possible auto transplantation of the lingual thyroid is recommended in those patients with significant dysphagia impeding oral intake, airway obstruction, hemorrhage, and other symptomatic presentations. [15,16] About 1% of lingual thyroids can convert to thyroid carcinoma, however, reported cases have occurred only in adults and was not considered concerning at this time given our patient’s young age and low lifetime risk. [17,18] However, pediatric interdisciplinary follow-up will continue to evaluate the status of the lingual thyroid, revisit imaging as she ages, and discuss possible surgical indications if warranted.

Congenital hypothyroidism is an entity not commonly encountered by a Pediatric Otolaryngologist. Laryngoscopy is performed for many indications in infants, and therefore an understanding of the pediatric lingual thyroid and variable presentation in congenital hypothyroidism can aid in differential diagnosis when a base of tongue mass is encountered. [19] Further, asymptomatic lingual thyroid, as described in this case is rarely reported in current literature. This case exemplifies the use of an interdisciplinary approach to successfully identify a lingual thyroid in a patient with congenital hypothyroidism, which involved general pediatrics, pediatric endocrinology and pediatric otolaryngology. Importantly, primary-care pediatricians should keep this clinical entity in mind when caring for infants with abnormal thyroid function and refer to otolaryngology and endocrinology as appropriate.

Interestingly, the patient’s lingual thyroid was found not to be causative of the hoarse voice, but rather that the vocal cord cyst was responsible for the vocal abnormality. This was determined upon six-month follow-up, in which the child’s voice abnormality and vocal cord cyst were both absent, despite the persistence of the lingual thyroid. Therefore, the lingual thyroid presentation was asymptomatic and the diagnosis was incidental.

The observed oral mass was diagnosed a lingual thyroid based on clinical history including the evaluation of a neck ultrasound, depicting the absence of a normal, pretracheal thyroid gland, and the clinical history of congenital hypothyroidism. The patient’s initial TSH level of 70.9 μIU/ml may have been suggestive of variable endogenous thyroid hormone production rather than an absent thyroid gland (athyreosis). Infants with athyreosis have a mean TSH of 255 μIU/ml, a level higher than those with ectopic thyroid. Yet variability does occur as TSH level can range from 67-701 μIU/ml for those with athyreosis, which can clinically blur the line between distinguishing infants with an ectopic thyroid or a true absent thyroid. [9] Further, at the time of diagnosis of congenital hypothyroidism the patient manifested overtreatment symptoms from the standard 50 mcg/day dose for full-term neonates and required reduction to 25 mcg/day. [10] Since two months of age the patient’s levothyroxine dosage was on the lower end of the guideline spectrum for hypothyroidism at 4 mcg/kg/day (normal 5-7 mcg/kg/day). [10] In retrospect, the patient’s clinical congenital hypothyroidism history and management plan was suggestive of trace hormone levels produced from an ectopic thyroid. Consultation with the pediatric Endocrinologist involved proved extremely valuable in determining whether further testing was warranted.

In other reported pediatric lingual thyroid cases, clinicians have performed a Technetium scan (Tc-99) to confirm that the lingual mass is representative of thyroid ectopic tissue, as differential diagnosis can include a thyroglossal duct cyst, dermoid cyst, vascular malformation, and valecular cyst. Here we present a case whereby the benefit of performing such imaging was not indicated. [11] Based on current literature it has been reported that thyroid gland uptake on Tc-99 imaging can be absent once levothyroxine therapy has been initiated.[12] Therefore, in order to properly image the patient, providers would have needed to discontinue the levothyroxine therapy for a period of time to induce her natural hypothyroid state to ensure accuracy of the scan. We deemed it was inappropriate to discontinue the patient’s levothyroxine supplementation given her young age and the well documented role of thyroid hormones impactful role on infant brain development within the literature. [13] While deeming that a Tc-99 scan was inappropriate at this time, the pediatric providers involved decided to revisit imaging in the future when the patient could safely be taken off of levothyroxine. We suggest considering Tc-99 imaging when patient’s reach three years of age, which has been demonstrated to be when brain development is less impacted by thyroid hormone levels. [14,15] The asymptomatic nature of the patient’s lingual thyroid also assisted the decision not to complete Tc-99 imaging at this time.

In addition, surgical intervention was deemed unnecessary, as the patient’s lingual thyroid remained asymptomatic, and medical management with levothyroxine therapy was continued. Surgical excision with possible auto transplantation of the lingual thyroid is recommended in those patients with significant dysphagia impeding oral intake, airway obstruction, hemorrhage, and other symptomatic presentations. [15,16] About 1% of lingual thyroids can convert to thyroid carcinoma, however, reported cases have occurred only in adults and was not considered concerning at this time given our patient’s young age and low lifetime risk. [17,18] However, pediatric interdisciplinary follow-up will continue to evaluate the status of the lingual thyroid, revisit imaging as she ages, and discuss possible surgical indications if warranted.

Congenital hypothyroidism is an entity not commonly encountered by a Pediatric Otolaryngologist. Laryngoscopy is performed for many indications in infants, and therefore an understanding of the pediatric lingual thyroid and variable presentation in congenital hypothyroidism can aid in differential diagnosis when a base of tongue mass is encountered. [19] Further, asymptomatic lingual thyroid, as described in this case is rarely reported in current literature. This case exemplifies the use of an interdisciplinary approach to successfully identify a lingual thyroid in a patient with congenital hypothyroidism, which involved general pediatrics, pediatric endocrinology and pediatric otolaryngology. Importantly, primary-care pediatricians should keep this clinical entity in mind when caring for infants with abnormal thyroid function and refer to otolaryngology and endocrinology as appropriate.

CONCLUSION

This case highlights the potential for ectopic, and possibly asymptomatic lingual thyroid, in patients with congenital hypothyroidism. Diagnosis with laryngoscopy of a base of tongue mass in this population aids in determining location of functioning thyroid tissue. The clinical implications and potential patient harm in utilizing Technetium imaging within pediatric patients for this diagnosis should be considered. Asymptomatic thyroid imaging warranting congenital hypothyroid pediatric patients to be taken off of their establish levothyroxine therapy should be considered with caution and we specifically suggest, if possible, re-evaluating imaging once the patient has reached at least three years old, with appropriate follow-up care. Clinical suspicion for this rare embryological anomaly must be shared across various pediatric specialties in order to ensure the identification of these patients. In cases of thyroid absence on ultrasound, an evaluation by an Otolaryngologist should be considered.

FUNDING SOURCE

NA

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE

NA

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

NA

REFERENCES

- Nilsson M, Fagman H (2018) Development of the thyroid gland. Development (Cambridge, England) 144: 2123-2140.

- Coran A, Coran A, Adzick N (2012) Pediatric surgery, (7th). Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, USA.

- Douglas PS, Baker AW (1994) Lingual thyroid. British Journal of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery 32: 123-124.

- Monroe JB, Fahey D (1975) Lingual thyroid. Arch Otolaryngol 101: 574-576.

- Kansal P, Sakati N, Rifai A, Woodhouse N (1987) Lingual thyroid. Diagnosis and Treatment. Archives of Internal Medicine. 147: 2046-2048.

- Burkart CM, Brinkman JA, Willging JP, Elluru RG (2005) Lingual cyst lined by squamous epithelium. International Journal Pediatric Otorhinolaryngoly 69: 1649-1653.

- Carranza Leon, Turcu A, Bahn R, Dean DS (2016) Lingual Thryoid: 35-Year Experience at a Tertiary Care Referral Center. Endocrine practice 22: 343-349.

- Williams JD, Sclafani AP, Slupchinskij O, Douge C (1996) Evaluation and management of the lingual thyroid gland. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology 105: 312-316.

- Lane L, Prudon S, Cheetham T, Powell S (2015) Acute neonatal respiratory distress caused by a lingual thyroid: The role of nasendoscopy and medical treatment. J Laryngol Otol 129: 403-405.

- Schoen E, Clapp W, To T, Fireman B (2004) The key role of newborn thyroid scintigraphy with isotopic iodide (123I) in defining and managing congenital hypothyroidism. Pediatrics 114: 1683-1668.

- DynaMed Plus [Internet]. Ipswich (MA): EBSCO Information Services. 1995-Record No.116588, Congenital hypothyroidism; [updated 2016 Mar 24, cited 2018, Nov 11.

- Rahmani K, Yarahmadi S, Etemad K, Koosha A, Mehrabi Y (2016) Congenital hypothyroidism: Optimal initial dosage and time of initiation of treatment: A systematic review. International journal of endocrinology and metabolism 14: 36080.

- Dutta D, Kumar M, Thukral A, Biswas D, Jain R (2013) Medical management of thyroid ectopia: Report of three cases. Journal of clinical research in pediatric endocrinology 5: 212-215.

- Lucas Herald A, Jones J, Attaie M, Maroo S, Neumann D, et al. (2014) Diagnostic and predictive value of ultrasound and isotope thyroid scanning, alone and in combination, in infants referred with Thyroid-stimulating hormone elevation on newborn screening. The Journal of Pediatrics 164: 846-854.

- Prezioso G, Giannini C, Chiarelli F (2018) Effect of thyroid hormones on neurons and neurodevelopment. Hormone research in pædiatrics 90: 73-81.

- Bernal J (2017) Thyroid hormone regulated genes in cerebral cortex development. Journal of Endocrinology 232: 83-97.

- Toso A, Colombani F, Averono G, Aluffi P, Pia F (2009) Lingual thyroid causing dysphagia and dyspnoea. Case reports and review of the literature. Actaotorhino-laryngologicaitalica 29: 213-217.

- Kumar S, Kumar D, Thirunavukuarasu R (2013) Lingual thyroid--conservative management or surgery? A case report. Indian Journal of Surgery 75: 118-119.

- Sturniolo G, Vermiglio F, Moleti M (2017) Thyroid cancer in lingual thyroid and thyroglossal duct cyst. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr 64: 40-43.

Citation: Peace MA, Fiorillo CE, Shimy K, Mudd P (2019) Incidental Finding of Lingual Thyroid in an Infant with Hoarseness. J Otolaryng Head Neck Surg 5: 033

Copyright: © 2019 Melissa A Peace, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Journal Highlights

© 2026, Copyrights Herald Scholarly Open Access. All Rights Reserved!