Integrating Social and Health Care Needs Assessment to Meet the Demand for Care of the Elderly in Italy: A National Cross-Sectional Study

*Corresponding Author(s):

Liotta GDepartment Of Biomedicine And Prevention, University Of Rome “Tor Vergata”, Via Montpellier 1, 00133-Rome, Italy

Tel:+39 0672596615,

Email:giuseppe.liotta@uniroma2.it

Abstract

Background: To size the demand for care generated by the population aged >75 years in Italy the authors conducted a secondary analysis of data stemming from the third wave of the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS- wave3), carried out in Italy in 2019, based on a harmonized questionnaire at European level.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional analysis carried out on the EHIS survey findings based on a randomized sample representative of the Italian population. Focusing on the people aged 75 and over, the number of people in need for care at national level has been estimated. The population was stratified in five groups that were defined using the quintiles of the probability distribution estimated by the logistic regression model on the outcome variable Global Activity Limitation Indicator.

Results: The total number of individuals aged >75 years who claim to have moderate/severe limitation of physical independence is estimated to be about 2.7 Million (95%CI: 2.6-2.8) at national level. Among them, about 1.3 million (95%CI: 1.2-1.4) declared they do not receive adequate help in relation to their care needs and experienced the urgency of receiving home care services. Approximately 260,000 (95%CI: 220,000- 300,000) individuals live alone and are included in the lower two quintiles of income, which makes it difficult for them to pay for personal care in the absence of public care services.

Conclusion: The integrated social and health assessment of the demand for care is a key element in planning community care targeting the older adults at the national level.

Keywords

Frailty; Health and social care; Long term care; Older adults; Social support

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Italy and probably in most western countries has revealed the fragility of the welfare, care, and support system based on non-residential community services. If it is well established that Long Term Care Facilities (LTCFs) have been a point of crisis both in Europe and in America [1], it is worth noting that something went wrong in primary care and home care services as well. As Salman R et al., [2] stated, primary care could be “…the cornerstone of pandemic response and has shown itself to be highly adaptable in meeting the unique demands of the pandemic” if adequately “…resourced with sufficient equipment, training, and financing.” However, the pandemic crisis revealed, in our opinion, not only an insufficient preparedness to face major disasters of public health services but also the need for a deep reform (at least in Italy) of the entire social care system for older adults. Gray and Sanders [3] pointed out that pandemics are pushing many changes in primary care and outlined the importance of integrated care, which has been debated for a long time. The Italian care and welfare system suffers from decades of formal and functional separation between social and health care, with social care in a situation of historical weakness, especially for older adults.

The Italian welfare system is characterised by the high cost of social security items in the social expenditure budget and interventions based largely on limited monetary transfers, rather than services. Despite law 328/2000, which provides for the integration of health care and social assistance, social care services are poorly funded in Italy compared to those in other European countries. In fact, the share allocated to the social function linked to disability is 5.7% of the social protection expenditure, while this percentage rises to 7.6% in European Union (EU).

An effect of the pandemic was the increase in loneliness, which has been well documented in another study [4], not only in nursing homes but also in the entire elderly population. In fact, the same effect was observed in a community-dwelling older adult population [5], especially for female subjects and those living alone. The role played by loneliness in exacerbating the COVID-19 epidemic in older adults is still under investigation. However, evidence suggest that social connectedness plays a positive role in reducing the incidence rate of negative outcomes [6,7]. The pandemic is just the most recent example of the harmful impact of loneliness and social isolation on physical and mental health. Moreover, we need to deeply understand the relationship between service offers and bio-psycho-social frailty in community-dwelling older adults, of which loneliness and social isolation are relevant components. To assess the older adults’ demand for community care based on the integration of health and social needs represents a simple and effective approach to define the human and monetary resources needed at the regional and national level in order to provide answers to the unmet care needs. This strategy is not implemented by any state/region in Europe, to our knowledge.

The aim of this paper was to size the demand for care generated by the population aged >75 years in Italy with special regard to mobility and Activities of Daily Living (ADL)/Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) impairment as well as social and economic resources in the pre-pandemic year.

Methods

In this study, we conducted a secondary analysis of data stemming from the third wave of the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS3), a health survey regulated by law [8] in all European countries, including the same topics and using European common methodology to obtain comparable European health indicators. Italian EHIS3 was conducted in two periods-between 15 April and 15 June 2019 and between 15 September and 31 December 2019.

The Italian EHIS3 sample was a multistage sample (municipalities/households). The sample frame was a Master Sample used for the permanent Census [9] including 2,850 municipalities and 1.4 million households. In the two-stage sampling design, 838 municipalities were extracted from this sample frame in the first stage. In the second stage, approximately 30,000 households were randomly selected. The final sample size was 22,796 households and 45,962 individuals aged ≥15 years, representing the resident population living in households at the regional and national levels.

The first step of the analysis was to calculate a composite indicator measuring the severity of health conditions and dependency of the elderly to divide the population into mutually exclusive groups. To this end, a logistic regression was performed on the outcome variable Global Activity Limitation Indicator (GALI), a self-measuring indicator of the presence of severe limitations in activities for health reasons, which is a good proxy for the need for care as a whole [10]. The standard wording of the GALI is as follows: ‘For at least the past 6 months, to what extent have you been limited because of a health problem in activities people usually do? Would you say you have been: severely limited, limited but not severely, not limited at all?’ Eurostat requested that the question and its translation be harmonised among all European countries to ensure the best comparability of the indicator given its relevance. In EHIS3, Eurostat proposed a version of the GALI for all countries divided into two questions. The first aimed at investigating the level of severity (‘Are you limited because of a health problem in activities people usually do? Would you say you are: severely limited, limited but not severely, not limited at all?’) and the second aimed at investigating the duration (‘Have you been limited for at least the past 6 months? Yes/No’).

The independent variables included as covariates in the analysis were functional limitations (severe difficulties in walking and/or in sight), severe difficulties in performing ADL [11] (not able to perform ADL) or IADL [12] (not able to perform IADL), and comorbidities (more than two chronic diseases). Five groups were defined using the quintiles of the probability distribution estimated by the logistic regression model. The other independent variables to describe groups 4 and 5, the ones showing the highest impairments, were lack of help, household income (quintiles, computed on the basis of the total equivalent disposable income - Elderly people belonging to the first quintile of income can be considered as a subgroup of elderly people living in greater economic difficulties, in many cases at risk of poverty) [13], living arrangements, and hospital admissions. Sex and age were included as control variables. The figures described in the results are based on national estimates stemming from the sample.

Results

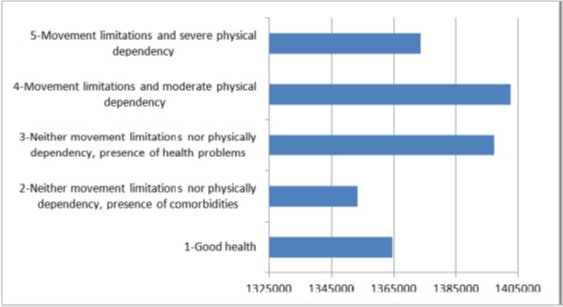

The total number of individuals aged >75 years who claim to have moderate/severe limitation of physical independence, according to the GALI, is estimated to be about 2,700,000 (95%CI: 2,600,000-2,800,000) (Figure 1, N. 4 and 5). The main characteristic of this population is the high physical impairment rate; about 40% show a moderate disability (severe difficulties in performing IADL) and 30% show a severe disability (severe difficulties in performing both instrumental and basic ADL).

Figure 1: Population aged >75 according to the prevalence of Chronic Diseases and Physical Impairment (N).

Figure 1: Population aged >75 according to the prevalence of Chronic Diseases and Physical Impairment (N).

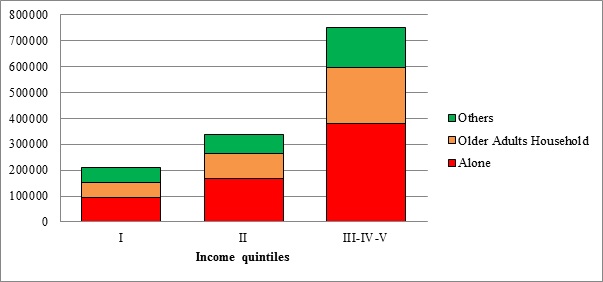

Among the 2.7 million, about 1.3 million (95%CI: 1.2-1.4; 20% of the 6.9 million Italians aged >75 years) is estimated to receive inadequate help in relation to their care needs (Figure 2). Among them, those who are completely alone (as many as 638,913 individuals) or who live with elderly cohabitants (372,735 individuals) and perceive a lack of adequate support, experience the urgency of receiving home care services. Approximately 260,000 individuals live alone (95%CI: 220,000-300,000) and are included in the lower two quintiles of income, which makes it difficult for them to pay for personal care in the absence of public care services. Older adults who are living alone and have poor economic resources, physical impairment, and a lack of help are in need of immediate action in terms of social assistance, without prejudice to further action on the health front. These are precious elements for dimensioning and modulating social, health, or integrated home care, as summarised in figure 3.

Figure 2: Population aged >75 and claiming for inadequate help by income quintiles and living arrangement (TOT 1.3 M).

Figure 2: Population aged >75 and claiming for inadequate help by income quintiles and living arrangement (TOT 1.3 M).

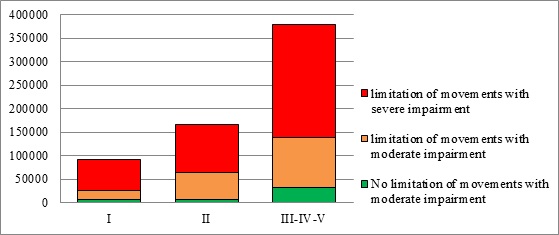

Figure 3: People aged >75 living alone and claiming for inadequate help by income quintiles and physical impairment (TOT 0.7 M).

Figure 3: People aged >75 living alone and claiming for inadequate help by income quintiles and physical impairment (TOT 0.7 M).

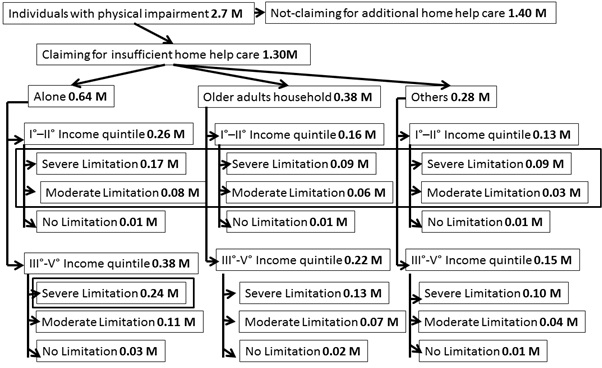

The estimated number of people with moderate/severe impairment in performing ADL who lacked support, did not acknowledge the need for help, and reported more than one hospitalisation in a year was approximately 11,000 (0.4% of the sample). The disproportionate amount of expenditure for care due to a small minority of subjects who became frequent users of hospital services is a well-known phenomenon [14]. Overall, the estimated total number of people with physical impairment associated with the absence of adequate personal support and sufficient resources to pay for care should be approximately 750,000 (Figure 4 - the lowest two income quintiles, including those who live alone and receive a monthly income higher than the 2nd quintile, who can face difficulties in paying for all the services they need). The remaining people could likely pay for at least part of the help they need, a condition that could drive the public services towards intervention rather than providing for personal care (orientation, support in seeking the right care services, seeking private care, or others).

Figure 4: Esteem of care demand according to physical condition and availability of social support and/or economic resources (number of individuals in millions).

Figure 4: Esteem of care demand according to physical condition and availability of social support and/or economic resources (number of individuals in millions).

Discussion

The integration of health and social care is a crucial step in making community care services more effective. The first step in integrating care is to integrate the assessment of the need for care. This step is not the usual procedure for community services. There are several reasons to explain this gap in planning community care. The first is the separation of fund sources, which is the rule in many EU countries, as in Italy. Usually, regional administrations manage the funds for health care and municipalities the ones for social care. Although many efforts have been made to find a model of funding integration, most EU countries are still in an experimental phase in this field, with different results. Usually, fund integration results in better care services because it underlines the need to place the person in the centre instead of the administrations and their attitude. However, the philosophy of integrated care requests an approach beyond the professional ‘silos’ which still dominates the provision of community care.

This approach is fostered by an assessment of care needs that joins both perspectives in a unique planning function. Many surveys at the EU level and at the national level are conducted without considering the cumulative impact of shortage of individual resources (social and economic) associated with psycho-physical impairment. From the perspective of personal care, this approach misses the point. However, many experiences at the local level move towards an integrated approach to assess the need for care [15]. This approach has several advantages, mainly the possibility of modelling the population on individuals’ needs for care, which is the basis for effective care planning. Functional status and inadequacy of the help received were assessed through interviews. Self-assessment of functional status is considered a valid method in several clinical situations [16], even if a gold standard to assess functional status does not exist [17].

Among the individuals who claim to receive inadequate help for their condition of life, the study identifies a group of people at higher risk of institutionalisation in the absence of an intervention. These individuals include those living alone and those with scarce economic resources, who represent a real emergency for the provision of community services (approximately 100,000 individuals). Immediately after them, we found older adults’ families with poor economic resources. The estimated number of people who need home care because of impairment in functional status and lack of social and economic resources is 700,000, which is about 10% of people aged >75 years. If we also include those who can probably pay something for the services, we reach 1.3 M (17.3% of people aged >75 years). It is worth noting that at the EU22 level, the average percentage of people aged >75 years reached by home care services is 14.6% (including both private and public services) and 15.9% of Italians aged >75 years self-report home care service use [18]. We could conclude that the need for care is substantially met; it is just a matter of helping people who are paying for services and cannot afford it to shift from private to public service. This is in conflict with the evidence in which a large number of the interviewees stated that they lacked the home help they needed. However, the EUROSTAT data explores only the provision of services, but it does not consider the intensity. In Italy, the last available national data on public home care services reports that 3.6% of people aged >65 years use the services (2.6% health services and 1% social services), which could be estimated as 7% of people aged >75 years [19]. Furthermore, a majority of individuals who declared that they receive home help services receive private services, most of whom are privately paid assistants. A considerable portion of the public health services (about 50%) is provided once a week or less, and another 20% is provided twice a week. Among people who receive home health care, the average time of care per person per year is 19 hours, which is sufficient to provide very limited services. Receiving home health care does not mean that the persons’ needs for care are met, but only that they receive few hours of care per year. With regard to social services, the estimated average provision of care amounts to 2 hours per week [20]. There is no documentation of the intensity and characteristics of private home care. These data indicate that the services do not meet the real needs for care of most of the people who are using them, except for those who have enough money to pay for what they need.

In the absence of effective home care provided by the public bodies when people lack economic resources, the only way is to be admitted in a long-term health care facility where the health care is paid by the Regional Health System and the social care costs are paid by the municipality where the person is resident in case he/she has insufficient income to pay for them. It is worth noting that about 50% of the interviewed respondents did not receive any home help, either private or public, even if they were not the same 50% who claimed to lack daily help. In other words, not all those who face severe/moderate impairment in performing ADL would apply for receiving additional care services at home. This could be due to a number of reasons:someone thinks he/she can manage with the help they already have (typically an old couple, who in turn is exposed to the sudden impairment/death of one of the partners that put the other one in immediate and sometimes massive need for care); someone else could think he/she does not need any help even if the situation is already deteriorating; someone else can count on children who can be forced to change their life because of an unexpected event. These are only a few examples that point out how the absence of an effective, easily accessible evaluation system opens the door to many unexpected and sudden situations that cannot be managed at home because of the shortage of time and the unpreparedness of a fractionated and separated care system.

Moreover, a real assessment of public economic provisions finalised to personal care provided to individuals is unclear. Individuals who are not self-sufficient are eligible for a care subsidy, but nobody knows whether a person cumulates public home care services and the subsidy, which in turn is sufficient to pay an average of 2 hours of care per day. Finally, the study reports a significant percentage of people in need of care because of their impairment without sufficient social and economic resources. Response time is a critical variable: when social and domestic support interventions are delayed, a vicious circle is established between the deterioration of health status and a further loss of functional skills.

A further concern is about individuals who need care but do not acknowledge it and usually face multiple hospital admissions. They are the ones who generate the highest care costs for public services. As an example, the cost of care data indicates that to reduce the frequent users of Emergency Department could generate the highest cost avoidance [21]. A proactive approach at the community level aimed at assessing the real need for care of older adults can provide useful information to prevent the frequent use of hospital services. The main limitations of the analysis are related to the lack of qualitative data sources and the nature of the data on which the analysis is based. In fact, the EHIS is not thought to join together different data, as we did.

Conclusion

This study confirms that the separation between social and health services hampers older adults’ care, both in terms of efficiency (increase in care cost) and effectiveness (decrease in individuals’ quality of life). The unmet social and economic needs for support generated by thousands of older adults, who are socially isolated and economically poor, is often associated with the worsening of their physical condition, which in turn increases the demand for health services with foreseeable consequences, like the increased demand for hospital admissions and residential long-term care and further loss of functional skills.

The discrepancy between the moderate/severe impairment in performing ADL/IADL and the need for care indicates the need for offering a multidimensional assessment to older adults to make evident the hidden need for care that is widely present in the population. The lack of awareness by the public services of the real need for care at the community level is likely one of the reasons for the ineffectiveness of interventions. This study is a starting point for planning community care services and is based on a multidimensional assessment that was performed on a large and representative sample of the Italian population for the first time, to the best of our knowledge. This approach to data provides valuable quantitative information for planning services at the population level, even if it cannot provide information on specific services. To acquire such data, it is necessary to administer multidimensional questionnaires focused on individual frailty and the connected need for home care services.

Keypoints

- Community-dwelling older adults suffer from many unmet care needs at the European level

- Main reason for unmet care needs is the lack of health and social services integration

- Health and social integration must start from an integrated needs assessment

- The use of an integrated approach to assess the care needs allow to size both financial and human resources needed to set up effective community care services

- This strategy is not yet implemented at the country level in European countries

Funding

The authors and their Institutions did not receive any funds for this paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Levere M, Rowan P, Wysocki A (2021) The Adverse Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Nursing Home Resident Well-Being. J Am Med Dir Assoc 22: 948-954.

- Rawaf S, Allen LN, Stigler FL, Kringos D, Yamamoto HQ, et al. (2020) Lessons on the COVID-19 pandemic, for and by primary care professionals worldwide. Eur J Gen Pract 26: 129-133.

- Gray R, Sanders C (2020) A reflection on the impact of COVID-19 on primary care in the United Kingdom. J Interprof Care 34: 672-678.

- Heidinger T, Richter L (2020) The Effect of COVID-19 on Loneliness in the Elderly. An Empirical Comparison of Pre-and Peri-Pandemic Loneliness in Community-Dwelling Elderly. Front Psychol 11: 585308.

- Savage RD, Wu W, Li J, Lawson A, Bronskill SE, et al. (2021) Loneliness among older adults in the community during COVID-19: A cross-sectional survey in Canada, BMJ Open 11: 044517.

- Liotta G, Marazzi MC, Orlando S, Palombi L (2020) Is social connectedness a risk factor for the spreading of COVID-19 among older adults? The Italian paradox. PLoS One 15: 0233329.

- Palombi L, Liotta G, Orlando S, Gialloreti LM, Marazzi MC (2020) Does the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic call for a new model of older people care? Front Public Health 8: 311.

- Eurostat (2021) European Health Interview Survey (EHIS wave 3) — Methodological manual. Eurostat, Germany.

- Istat (2021) Permanent Census of Population and Housing. Istat, Rome, Italy.

- Rubio-Valverde JR, Nusselder WJ, Mackenbach JP (2019) Educational inequalities in Global Activity Limitation Indicator disability in 28 European Countries: Does the choice of survey matter? Int J Public Health 64: 461-474.

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW (1963) Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185: 94-919.

- Lawton MP, Brody EM (1969) Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9: 179-186.

- Eurostat (2021) Glossary:Equivalised disposable income accessed on 15.07.2021. Eurostat, Germany.

- Liotta G, Gilardi F, Orlando S, Rocco G, Proietti MG, et al. (2019) Cost of hospital care for the older adults according to their level of frailty. A cohort study in the Lazio region, Italy, PLoS One 14: 0217829.

- van Duijn S, Zonneveld N, Lara Montero A, Minkman M, Nies H (2018) Service Integration Across Sectors in Europe: Literature and Practice. Int J Integr Care 18: 6.

- Boucher V, Boucher V, Lamontagne M, Lee J, Émond M (2020) P130: feasibility of self-assessing functional status in older emergency department patients, Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine 22: 111.

- Murat F, Ibrahim Z, Chan YM, Adznam SN, Adznam A (2017) Assessment of functional status through self-reported physical disability and performance-based functional limitations among elderly, Int J Human Social Sci Inven 6: 2319-7722.

- Eurostat (2021) Preliminary results for EHIS 2019. Eurostat,

- NNA (2017) L’ASSISTENZA AGLI ANZIANI NON AUTOSUFFICIENTI IN ITALIA - 6° Rapporto 2017/2018 (2019) (Assistance to non self-sufficient elderly in Italy - 6th Report 2017/2018). NNA, Italy.

- NNA (2021) L’ASSISTENZA AGLI ANZIANI NON AUTOSUFFICIENTI IN ITALIA - 7° Rapporto 2020/2021 (2021) (Assistance to non self-sufficient elderly in Italy - 6th Report 2020/2021). NNA, Italy.

- Cheney C (2020) Target long-term emergency room frequent users to curb visits and cut cost. HealthLeaders.

Citation: Palombi L, Liotta G, Gargiulo L, Iannucci L, Burgio A, et al. (2022) Integrating Social and Health Care Needs Assessment to Meet the Demand for Care of the Elderly in Italy: A National Cross-Sectional Study. J Gerontol Geriatr Med 8: 118.

Copyright: © 2022 Palombi L, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.