Intermittent Vibration Increases Methamphetamine Intake in Rats

Abstract

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Numerous studies have used loud noise as a stress stimulus, and demonstrated increases in stress hormones such as epinephrine and cortisol that are then implicated in the manifestation of stress-associated physiological disorders [8]. Whole-body vibration can alter autonomic and neuroendocrine responses to stress, by increasing the limbic secretion of factors that regulate hypothalamic-pituitary function such as vasoactive intestinal peptide [9] and substance-P or neurotensin [10]. In a separate study, whole-body vibrational stress decreased norepinephrine levels in whole brain as well as in the hypothalamus and hippocampus [11]. Fewer investigations into the effects of noise or vibration on drug intake have been published. However, one study found that conditioned place preference to MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine; “ecstasy”) was enhanced by exposure to noise in rats [12]. Paradoxically, loud noise was shown to enhance MDMA-induced toxicity in nigrostriatal dopaminergic terminals in mice [13], and the combination of Methamphetamine (METH) and loud noise in mice has been shown to increase the number of seizures and the amount of reactive gliosis in the brain compared to METH alone [14]. In summary, the ability of vibration or noise to serve as stressors in animal studies is clear and the eradication of these stimuli is critical for effective experimental design and analysis. This is especially true in studies where stress is applied as an independent variable or measured as an outcome of the experimental design.

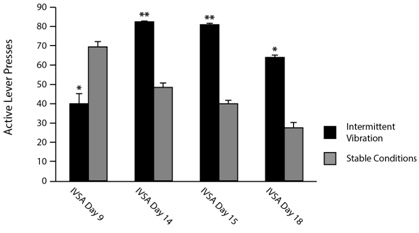

We recently conducted a study on METH Intravenous Self-Administration (IVSA) in young adult male rats, with and without prior exposure to restraint stress. At the time of behavioral analysis for one cohort, a large construction project was initiated on our campus outside of the building in which the animals were housed and tested. While efforts were made to minimize the impact of the noise inside our facility, the intermittent vibration and changes in noise levels induced by the use of heavy machinery became a concern once the construction began. Indeed, observation of the animals in the IVSA chambers allowed us to qualitatively determine changes in behavior that occurred as a consequence of the environmental disruption. Overall, locomotor activity appeared to increase in the rats compared to that seen in previous cohorts tested prior to construction onset. This enhanced locomotion likely increased lever pressing in total, however, with the rats displaying less discrimination between the active (drug-delivering) and inactive (no reward) levers.

A subsequent quantitative evaluation of performance yielded the results shown in figure 1. Young adult male rats that were given access to METH IVSA during the construction period did in fact show significantly different numbers of presses on the active lever compared to rats of the same age and sex who were not exposed to construction. On day 9, when construction was initiated and the intermittent vibration and noise stimuli began, exposed rats showed diminished active lever pressing compared to rats from an unexposed cohort tested previously under stable conditions. Subsequent testing on days 14, 15 and 18 of the IVSA protocol, in contrast, showed significantly increased active lever responding in the rats exposed to intermittent vibration, compared to non-exposed rats which displayed consistent reductions in their active lever pressing. Normally, reduced active lever pressing is seen over time as the rats learn to press when drug is available (cue-induced) as opposed to pressing during the time-out period when no drug will be delivered. In the intermittent vibration cohort, however, the opposite effect was observed. Rats exposed to vibration had reduced locomotor activity and made fewer presses on the active lever at the start of the construction, but subsequently showed increased locomotion and increased lever pressing on both the active and inactive levers. While this response was not one that specifically induced a higher degree of drug seeking, as inactive lever presses failed to yield any reward, these rats did receive increased amounts of drug throughout the study. These results demonstrate that behavior was markedly affected by the intermittent vibration experienced by the “construction” cohort, leading to increased drug intake. Furthermore, the experience of a secondary stress in the form of vibration or noise after a pre-conditioning restraint stress significantly altered locomotor and drug taking patterns in our animals. Our data is supported by recent findings from another institution, in which construction occurring in close proximity to an animal facility was shown to alterrenin-angiotensin system activity and stress hormones at multiple levels of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [15]. In addition, stress history and novel environmental conditions have been shown to be predictive of patterns of METH taking in rodents [16].

Together, these observations underscore the impact that different types of stressors and the timing in which they are experienced can have on drug intake in animal studies, and highlight the importance of environmental stimuli in experiments of this type. Translating these findings to human drug use behavior will require further studies, but stress has been established as a contributing factor to relapse as well as the development and persistence of addiction in humans, as reviewed recently [17]. Environmental stimuli in increase stress, especially when experienced sequentially with limited time intervals in between them, may increase drug use or the risk for addiction in humans as well as animals.

DISCLAIMER

This short review was written in a personal capacity and does not necessarily represent the opinions of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the National Institutes of Health, the US Department of Health and Human Services, or the US Federal Government.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by the Vulnerability Issues in Drug Abuse (VIDA) Project (NIH/NIDA R24 DA029989), the Border Biomedical Research Center (BBRC; NIH/NIGMS G12 MD007592), and the SMART MIND program (NIH/NIDA R25 DA033613). Additionally, we would like to thank Jameel Hamdan for his work on the project, as well as the BBRC Biomolecule Analysis and Genomic Analysis Core Facilities and the UTEP Laboratory Animal Resources Center.

REFERENCES

- National Research Council/National Academy of Sciences (2011) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, (8th edn), Institute of Laboratory Animal Research, National Academy Press, Washington DC, USA.

- Rasmussen S, Glickman G, Norinsky R, Quimby FW, Tolwani RJ (2009) Construction noise decreases reproductive efficiency in mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 48: 363-370.

- Nayfield KC, Besch EL (1981) Comparative responses of rabbits and rats to elevated noise. Lab Anim Sci 31: 386-390.

- Beckett SR, Duxon MS, Aspley S, Marsden CA (1997) Central c-fos expression following 20kHz/ultrasound induced defence behaviour in the rat. Brain Res Bull 42: 421-426.

- Carman RA, Quimby FW, Glickman GM (2007) The effect of vibration on pregnant laboratory mice. Noise-Con Proc 209: 1722-1731.

- Briese V, Fanghänel J, Gasow H (1984) [Effect of pure sound and vibration on the embryonic development of the mouse]. Zentralbl Gynakol 106: 379-388.

- Rabey KN, Li Y, Norton JN, Reynolds RP, Schmitt D (2015) Vibrating Frequency Thresholds in Mice and Rats: Implications for the Effects of Vibrations on Animal Health. Ann Biomed Eng 43: 1957-1964.

- Babisch W (2003) Stress hormones in the research on cardiovascular effects of noise. Noise Health 5: 1-11.

- Nakamura H, Moroji T, Nagase H, Okazawa T, Okada A (1994) Changes of cerebral vasoactive intestinal polypeptide- and somatostatin-like immunoreactivity induced by noise and whole-body vibration in the rat. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 68: 62-67.

- Nakamura H, Moroji T, Nohara S, Nakamura H, Okada A (1990) Effects of whole-body vibration stress on substance P- and neurotensin-like immunoreactivity in the rat brain. Environ Res 52: 155-163.

- Okada A, Ariizumi M, Okamoto G (1983) Changes in cerebral norepinephrine induced by vibration or noise stress. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 52: 94-97.

- Feduccia AA, Duvauchelle CL (2008) Auditory stimuli enhance MDMA-conditioned reward and MDMA-induced nucleus accumbens dopamine, serotonin and locomotor responses. Brain Res Bull 77: 189-196.

- Gesi M, Ferrucci M, Giusiani M, Lenzi P, Lazzeri G, et al. (2004) Loud noise enhances nigrostriatal dopamine toxicity induced by MDMA in mice. Microsc Res Tech 64: 297-303.

- Morton AJ, Hickey MA, Dean LC (2001) Methamphetamine toxicity in mice is potentiated by exposure to loud music. Neuroreport 12: 3277-3281.

- Raff H, Bruder ED, Cullinan WE, Ziegler DR, Cohen EP (2011) Effect of animal facility construction on basal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and renin-aldosterone activity in the rat. Endocrinol 152: 1218-1221.

- Taylor SB, Watterson LR, Kufahl PR, Nemirovsky NE, Tomek SE, and at all (2016) Chronic variable stress and intravenous methamphetamine self-administration - Role of individual differences in behavioral and physiological reactivity to novelty. Neuropharmacol 108: 353-363.

- Mantsch JR, Baker DA, Funk D, Lê AD, Shaham Y (2016) Stress-Induced Reinstatement of Drug Seeking: 20 Years of Progress. Neuropsychopharmaco l41: 335-56.

Citation: Gosselink KL (2016) Intermittent Vibration Increases Methamphetamine Intake in Rats. J Alcohol Drug Depend Subst Abus 2: 005.

Copyright: © 2016 Kristin L Gosselink, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.