Investigating the Impact of a Plant-Based Remedy on Tissue Regeneration in Human Fibroblasts and Keratinocytes: An In-vitro Analysis

*Corresponding Author(s):

Victoria Franziska StruckmannDepartment Of Hand, Plastic, And Reconstructive Surgery, BG Klinik Ludwigshafen, Burn Center At Heidelberg University, Ludwig-Guttmann-Str. 13, Ludwigshafen, Germany

Tel:+49 62168108961,

Email:victoria.struckmann@bgu-ludwigshafen.de

Abstract

Background: Tissue regeneration, including wound healing, continues to pose a significant challenge in modern medicine. As chronic wounds become more prevalent due to demographic changes and lifestyle factors, there is growing interest in alternative therapeutic approaches. Phytotherapy, particularly the use of plant-based preparations, is gaining traction as a cost-effective, accessible, and well-tolerated alternative to conventional treatments. To better understand its effects on tissue regeneration, a commercially available plant-based remedy was analyzed.

Methods: Human fibroblasts (BJ, ATCC® CRL-2522™) and keratinocytes (HaCaT) were incubated with the test substance, in serial dilutions from 10 to 0,00001 %. Cell vitality was assessed by determining the cell count through ATP-dependent metabolic activity using the CellTiter-Glo® (CTG) assay, as well as by tetrazolium reduction (MTT assay).

Cell proliferation was analyzed by the incorporation of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) into the DNA of actively proliferating cells.

The Wound Healing Assay (WHA) helped to quantify cell migration.

Additionally, the expression of specific key genes was determined by real-time PCR, and protein expression related to inflammation, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis was assessed via proteome array.

Results: An incubation of BJ and HaCaT cells with the test substance for 24/72 hours showed no reduction in cell number, viability or proliferation in physiological dilution. Cell migration was unimpaired. The test substance induced several inflammatory genes (IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, VEGFA, TGF) and increased protein expression of various inflammatory cytokines in the HaCaT and BJ cells.

Conclusion: The test substance did not impair cell vitality parameters (MTT, CTG, BrdU and WHA). A tendency of bioactivity with activation of growth factors, inflammatory genes and proteins was shown for fibroblasts as well as keratinocytes, indicating a possible positive effect on tissue regeneration processes.

Keywords

BJ; HaCaT; Plant-Based Remedy; Tissue Regeneration

Introduction

As the largest organ of the human body, covering approximately 2 m², the skin serves as a primary barrier against environmental insults, including physical trauma, pathogens, and chemical exposure. It plays a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis by preventing dehydration, contributing to immune surveillance, and facilitating cutaneous vitamin D synthesis. Upon injury, the skin initiates a tightly regulated wound healing cascade to restore structural and functional integrity [1,2].

Wound healing is categorized as either primary or secondary. Primary healing involves rapid tissue repair with minimal residual damage, whereas secondary healing is typically slower and often results in scar formation. This regenerative process can be significantly impaired by factors such as infection, malnutrition, chronic conditions like diabetes [3] and the natural ageing process [4]. Due to the influence of such impairing factors, chronic wounds represent an increasing clinical burden, particularly among the elderly, and impose significant strain on healthcare systems worldwide.

Disruption of the skin barrier compromises its protective function and simultaneously initiates a local immune response. Cellular and tissue damage results in the release of Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs), which activate components of the innate immune system, including immune cells and the complement cascade. These activated cells secrete cytokines—soluble proteohormones that mediate intercellular communication through paracrine, autocrine, and endocrine mechanisms. Cytokines regulate a wide array of processes, including the activation of downstream signaling pathways, modulation of adaptive immunity, and control of cell differentiation, proliferation, and growth. To prevent systemic spread, tightly regulated pro-inflammatory and counter-regulatory mechanisms are initiated to confine the inflammatory response to the site of injury [5]. While inflammation is essential for initiating tissue repair, a prolonged or excessive inflammatory response can disrupt the healing process and contribute to chronic wound pathology [6]. Wound tissue provides a favorable environment for microbial colonization, which can significantly delay healing and, in some cases, lead to chronic wound formation. Persistent infection increases the risk of systemic complications such as sepsis, potentially resulting in life-threatening outcomes [7,8]

Aging is associated with reduced regenerative capacity due to the functional decline of stem cells [4]. In aging skin, the number of Langerhans cells—key antigen-presenting cells bridging innate and adaptive immunity—declines, compromising cutaneous immune surveillance [9]. Advancing age is associated with an increased risk of impaired wound healing. In light of demographic shifts, this issue is gaining clinical and societal relevance. The growing incidence of chronic wounds imposes a progressively greater economic burden on healthcare systems [10].

Medicinal plants have long supported wound healing, with phytotherapy gaining attention for its accessibility, low cost, and favorable safety profile. While individual plant compounds show promising effects in vitro and in vivo, evidence on complex formulations such as spagyric-homeopathic remedies remains limited [11-17]. Plant extracts are also utilized in surgical contexts, with multiple studies reporting improved outcomes when integrated into wound dressings [2,18,19].

This study aims to investigate the effect of the plant-based complex substance OpsonatTM on tissue regeneration in vitro, focusing on its influence on fibroblast and keratinocyte cell proliferation, as well as its impact on inflammatory pathways. By exploring these mechanisms, the study seeks to further understand the potential therapeutic role of plant-based formulations in enhancing wound healing.

Methods

The test substance used in this study is a homeopathic spagyric medicine, prepared using the spagyric preparation method according to PEKANA (HAB 2024, §§ 47a-b) by PEKANA Naturheilmittel GmbH (Kißlegg, Germany) and kindly provided for this study.

At the end of a four-step manufacturing process - comprising separation, purification, calcination, and union - a standardized, complex natural mixture is obtained. Unlike classical homeopathy, the product is used either undiluted (mother tincture) or in low dilutions (D1–D7), retaining measurable active components [20].

Test substance

The homeopathic-spagyric remedy, OpsonatTM, is manufactured by PEKANA Naturheilmittel GmbH (Kisslegg, Germany) and used for the treatment of inflammations of skin and mucous membranes. It consists of several herbal ingredients, inter alia Bellis perennis, with acidum nitricum and sulfuricum, Lytta vesicatoria as well as Lechesis mutus being the non-plant components (Table 1). All of these have a long tradition in the preparation of medicines according to the homeopathic pharmacopoeia.

A carrier control was prepared by the manufacturer using a pure ethanol–water mixture without active ingredients, following the same procedure as for the test substance. Active ingredients can be found in table 1. The recommended oral dosage of Opsonat® ranges from 20 to 60 drops, corresponding to approximately 1-3 mL (1 drop ≈ 50 µL) three times a day. Assuming an average human body weight of 80 kg with 70 % water content and homogeneous distribution of the compounds in an aqueous phase without tissue binding, this corresponds to an estimated dilution range of 1:42.000 to 1:224.000.

German homeopathic pharmacopoeia, GHP; European Pharmacopoeia, Ph.Eur.

|

Ingredients |

manufacturing method |

potency |

per 10 g |

|

Acidum nitricum |

GHP,5a / Ph.Eur.3.1.1 |

D4 |

1,60 g |

|

Acidum sulfuricum |

GHP,5a / Ph.Eur.3.1.1 |

D4 |

1,25g |

|

Bellis perennis spag. Peka |

GHP,47a |

D1 |

1,15 g |

|

Glechoma hederacea spag. Peka |

GHP,47a |

MT |

1,65g |

|

Gratiola officinalis 3b |

GHP,3b / Ph.Eur.1.1.6 |

D4 |

1,25g |

|

Hydrastis canadensis |

GHP,4a / Ph.Eur.1.1.8 |

D4 |

0,55g |

|

Lachesis mutus |

GHP,SV 5a / Ph.Eur.3.1.1 |

D7 |

1,40g |

|

Lytta vesicatoria (=Cantharis) |

GHP,4b / Ph.Eur.1.1.9 |

D4 |

1,15g |

|

excipiens |

|

|

|

|

Aqua purificata |

|

|

|

|

Ethanol |

|

|

25 Vol.-% |

Table 1: Ingredients of Opsonat.

The remedy is prepared according to the German homeopathic pharmacopoeia (GHP), containing test specification for homeopathic medicinal products. The GHP specifies according to which regulation the respective plant is to be prepared.

Adolescents from 12 years and adults take 20 drops three times a day. Children from 2 to 11 years: 10 drops three times a day. So far, no studies have been carried out on the concentration in humans.

Ethical Review Board: The Ethics Committee of Rheinland-Pfalz waived to provide ethics approval, since the study was performed with commercially available cell lines only.

Cell culture

Human fibroblasts cell line (BJ cells, ATCC® CRL-2522™) was obtained from ATCC (LGC Standards, Wesel, Germany).

Human adult keratinocyte cell line (HaCaT cells) was obtained from Cytion (Heidelberg, Germany).

For experimental use, cell lines were expanded by rapid thawing in pre-warmed medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s-medium, 10% Fetal calf serum, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin) followed by centrifugation to remove cryoprotectant. Cells were seeded in T150 flasks at BJ ca. 6x103/cm2, HaCaT ca. 3x103/cm2. After 24 hours, non-adherent cells and residual cryomedium were removed via medium change. Cultures were maintained in medium pre-warmed to 37°C. Upon reaching >90% confluency, cells were either passaged, stored at −80°C, or directly used in experiments. Centrifugation was performed at 300 × g for 5 minutes. Both cultures were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity.

CTG assay

BJ and HaCaT cells were seeded into flat-bottom 96-well plates (TPP, Switzerland) at a density of 1×104 cells per well in 100µL culture medium. After 16h incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2, the medium was removed, and cells were treated with 100µL of serial dilutions (10% to 0.000001%) of the test compound or vehicle control (n=8). Controls included wells with medium only (untreated, n=16) and wells without cells (negative control). Cells were incubated for 24 and 72h under the same conditions.

Cell viability was assessed via ATP quantification using the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Germany). An equal volume of CTG reagent was added to each well, mixed gently, and luminescence was measured after 10 minutes using a GloMax® plate reader (Promega, Germany).

MTT assay

Cellular metabolic activity was assessed using the MTT assay, following the same setup as the CTG assay. After 24 or 72h incubation, MTT reagent (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) was added to a final concentration of 0.5mg/mL. Following additional incubation, the supernatant was removed, and 100µL of DMSO were added to dissolve formazan crystals. Plates were gently shaken, and absorbance was recorded at 572nm and 620nm using a Multiscan™ FC Microplate Photometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

BrdU Proliferation Assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated using the BrdU Cell Proliferation Kit (CHEMICON®, Millipore, Merck KGaA, Germany) in 96-well plates containing the test substance and carrier control (n=4), as well as untreated, negative, and background controls (n=8). The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol, with cells incubated for 24 and 72h in the presence of BrdU. Absorbance was measured at 450nm and 596nm using the Multiscan™ FC Microplate Photometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Scratch Assay

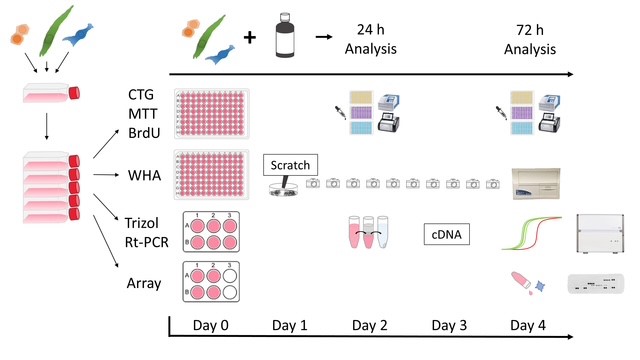

Cell migration was assessed using a Wound Healing Assay (WHA) on an Incucyte® S2 live-cell imaging system (Essen BioScience, UK). Cells were seeded at 3×104 per well in 96-well ImageLock plates (Essen BioScience), following the CTG assay setup. Scratches were introduced using the manufacturer-recommended tool, and cell debris was removed with two PBS washes. Test medium was then added, and plates were placed in the pre-warmed imager (37°C). Experimental layout and imaging parameters were set using Map Editor and Incucyte® Zoom software. Images were captured every 2 hours over a 72-hour period (Figure 1).

Figure 1: provides a systematic overview of the experiments conducted in this study. The setup was the same at the beginning for all methods and cell lines. After reaching the required cell amount, the cells were distributed on day 0 into plate formats (Table 2) appropriate for each specific experiment.

Figure 1: provides a systematic overview of the experiments conducted in this study. The setup was the same at the beginning for all methods and cell lines. After reaching the required cell amount, the cells were distributed on day 0 into plate formats (Table 2) appropriate for each specific experiment.

|

test |

format |

n sample |

µL/Well |

cells/Well |

|

|

BJ |

HaCaT |

||||

|

CTG |

96-Well |

8 |

100 |

1x104 |

1x104 |

|

MTT |

96-Well |

8 |

100 |

1x104 |

1x104 |

|

BrdU |

96-Well |

4 |

100 |

1x104 |

1x104 |

|

WHA |

96-Well |

8 |

|

1x104 |

6x104 * |

|

Trifast |

6-Well |

2 |

|

2x105 |

2x105 |

|

Array |

6-Well |

2** |

|

2x105 |

2x105 |

Table 2: List of methods for cell culture tests.

*after 4h scratch

**duplicates were combined after the supernatant was collected.

Test methods: CTG (CellTiterGlo Test), MTT (MTT-Test with Tetrazoliumsalt), BrdU (BrdU Test with Bromdesoxyuridin), WHA (wound healing assay), Trifast (Trizol RNA Isolation method for gene expression testing), Cytokine Array (Array for detection of protein expression from cell supernatant.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and gene expression analysis

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates (TPP) at 2×105 cells/well (n=3). After 24h, 2mL of the test substance or carrier control (serial dilutions: 1%, 0.01%, 0.0001%, 0.000001%) or medium alone (untreated control) were added.

Following 24h of incubation, total RNA was extracted using the TriFast™ reagent (VWR Peqlab, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was resuspended in 10µL DNase working solution (RNase-free DNase Set, Qiagen), incubated for 15min, and DNase was inactivated at 65°C for 5min. Samples were diluted with 10µL nuclease-free water and quantified using a BioSpectrometer® (Eppendorf, Germany) at 1:50 dilution. RNA samples were stored at −80°C.

cDNA was synthesized from 1µg total RNA using the Omniscript® Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s instructions, and stored at −20°C.

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed using the LightCycler® 480 system and SYBR® Green I Master Mix (Roche Diagnostics, Germany). Each 10µL reaction contained 5µL SYBR® Green Mix, 3µL nuclease-free water, 0.5µL of each primer (10µM), and 1µL cDNA (or water for negative controls). The thermal cycling program was: 95°C for 5min, followed by 55 cycles of 95°C for 10s, 60°C for 20s, and 72°C for 20s; followed by melt curve analysis. Gene expression was quantified using a standard-curve-based, efficiency-corrected method and normalized to 18S rRNA. Primer sequences are listed in table 3.

|

gene name |

gene bank number |

primer sequence 5’ -3’ |

product size [bp] |

hybridization temperature [°C] |

|

IL-1α

|

NM_000575.5

|

fw gcgtttgagtcagcaaagaagt rv catggagtgggccatagctt |

159

|

60

|

|

IL-6

|

NM_00600.5

|

fw caatgaggagacttgcctgg rv gcacagctctggcttgttcc |

113

|

60

|

|

IL-8

|

NM_00584.4

|

fw gaagtttttgaagagggctgaga rv tttgcttgaagtttcactggca |

92

|

60

|

|

IL-10

|

NM_000572.3

|

fw ccagacatcaaggcgcatgt rv cattcttcacctgctccacgg |

127

|

60

|

|

TGF

|

NM_000660.5

|

fw acagcaacaattcctggcga rv caatttcccctccacggctc |

123

|

60

|

|

VEGFA

|

NM_001171627.1

|

fw agaaaatccctgtgggcctt rv ctcggcttgtcacatcttgc |

118

|

60

|

Table 3: Primers used in this study.

Proteome Profiling

Cytokine expression was assessed using the Proteome Profiler Human Cytokine Array Kit (ARY005B, R&D Systems, USA). Cells were seeded in 6-well plates (2×105 cells/well). After 24h, test or carrier substances (0.0001% and 0.000001%) were added (n=2 per group). After 72h, culture supernatants were collected, pooled per group, and kept on ice. Samples were centrifuged at 300×g for 10min at 4°C and stored at −20°C. Arrays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions after thawing the samples on ice.

Statistical analysis

For each data set averages, standard error of mean and statistical significance were calculated using Microsoft Excel. Significances were calculated using unpaired, unequal variances t-test (Welch t-test).

Results

Effect of the test substance on keratinocyte and fibroblast cell viability and proliferation

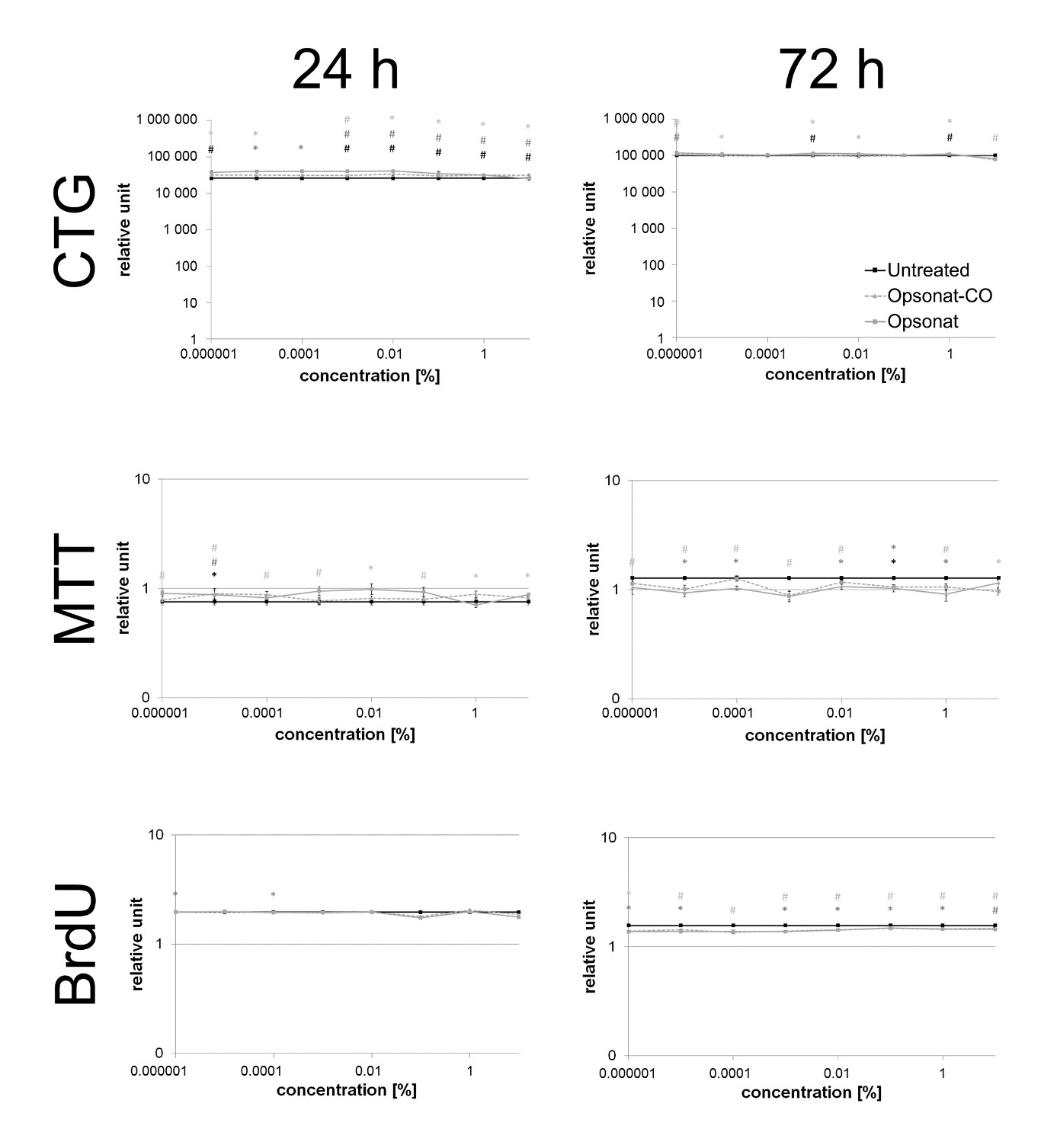

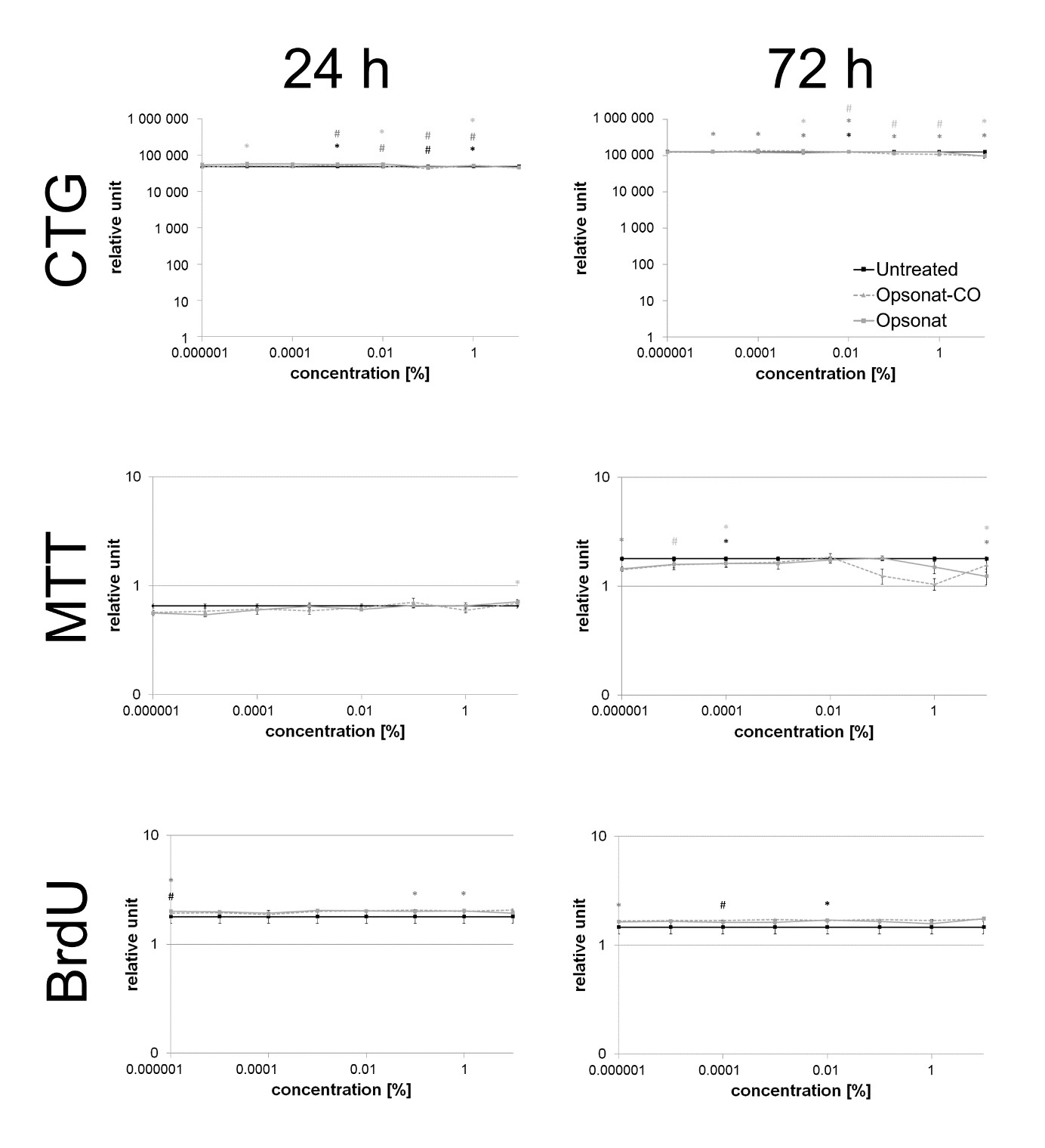

Cells treated with the test substance exhibited absorbance values comparable to those of carrier-treated and untreated controls. A slight reduction in viability and proliferation was observed only at higher concentrations of both the test and carrier substances (Figures 2 & 3).

Figure 2: Cell viability and proliferation in BJ.

Figure 2: Cell viability and proliferation in BJ.

Cell viability and proliferation of BJ fibroblasts (CTG, MTT and BrdU) were measured after 24 hours and 72 hours. A p-value < 0.05 shown as * and a p-value < 0.005 shown as # are determined as statistically significant. Significance between test substance and carrier substance is shown as black, between test substance and untreated control shown as dark grey and carrier substance and untreated control shown as light grey.

Figure 3: Cell viability and proliferation in HaCat.

Figure 3: Cell viability and proliferation in HaCat.

Cell viability and proliferation of HaCat keratinocytes (CTG, MTT and BrdU) were measured after 24 hours and 72 hours. A p-value < 0.05 shown as * and a p-value < 0.005 shown as # are determined as statistically significant. Significance between test substance and carrier substance is shown as black, between test substance and untreated control shown as dark grey and carrier substance and untreated control shown as light grey.

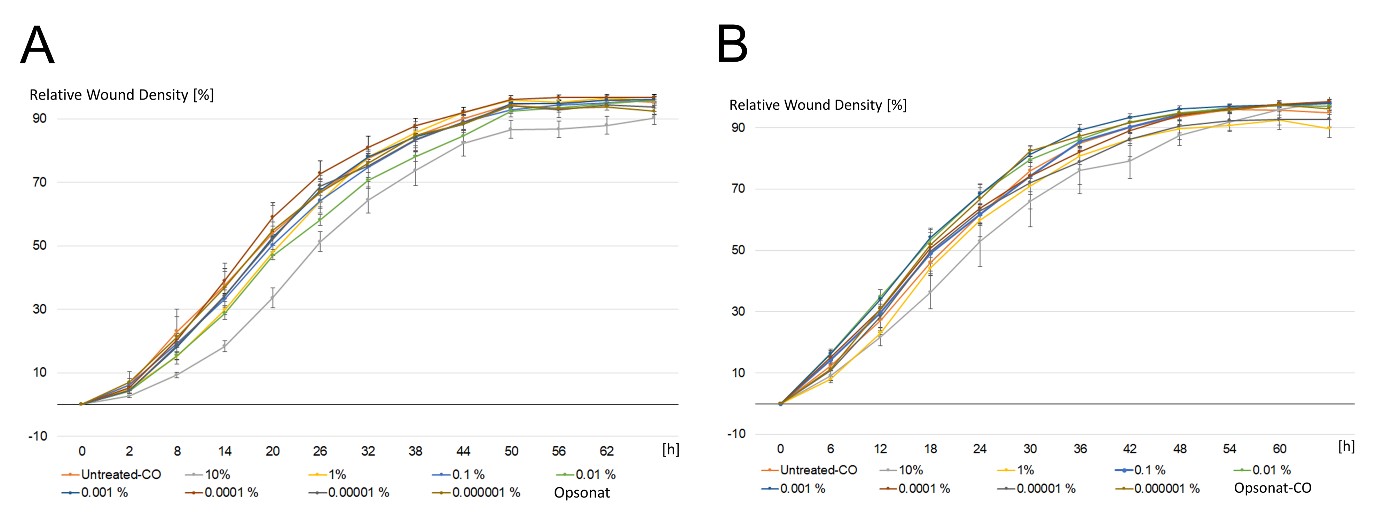

Cell migration and wound healing

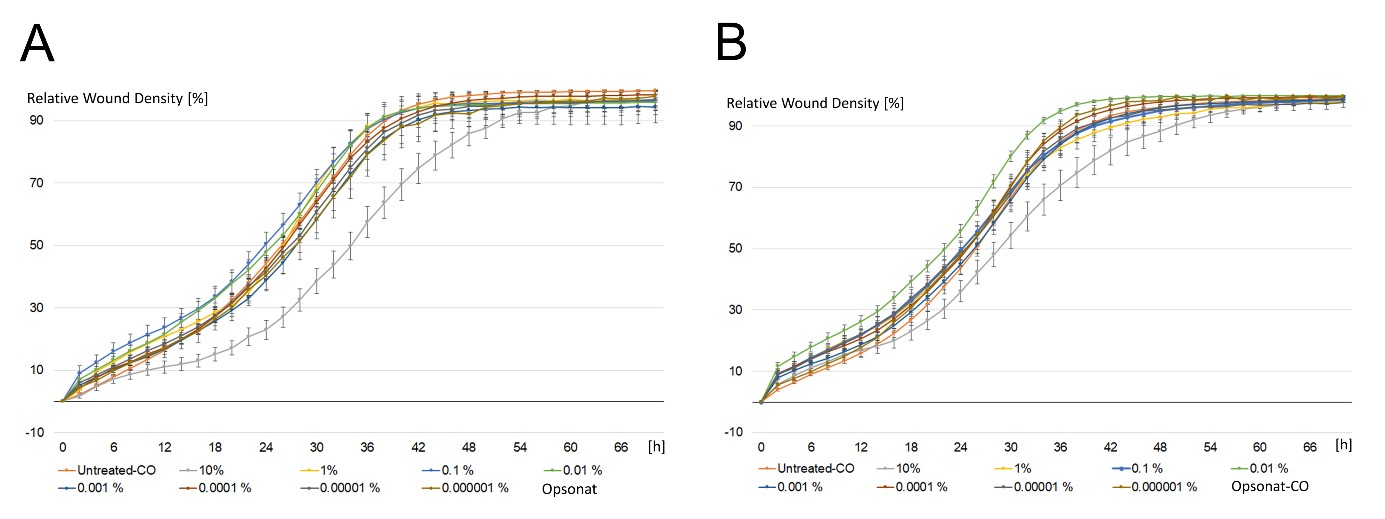

BJ cells demonstrated robust migratory capacity, closing >90% of the scratch within 42–44 hours. Treatment with the highest concentration (10%) of test substance or carrier resulted in delayed wound closure (54–80 hours). At lower concentrations, Opsonat®-treated BJ cells closed the scratch in 44–50 hours (mean: 48h), compared to 44h for untreated controls. Carrier-treated BJ cells closed the wound in 42–54 hours (mean: 45h), versus 42h for controls (Figure 4).

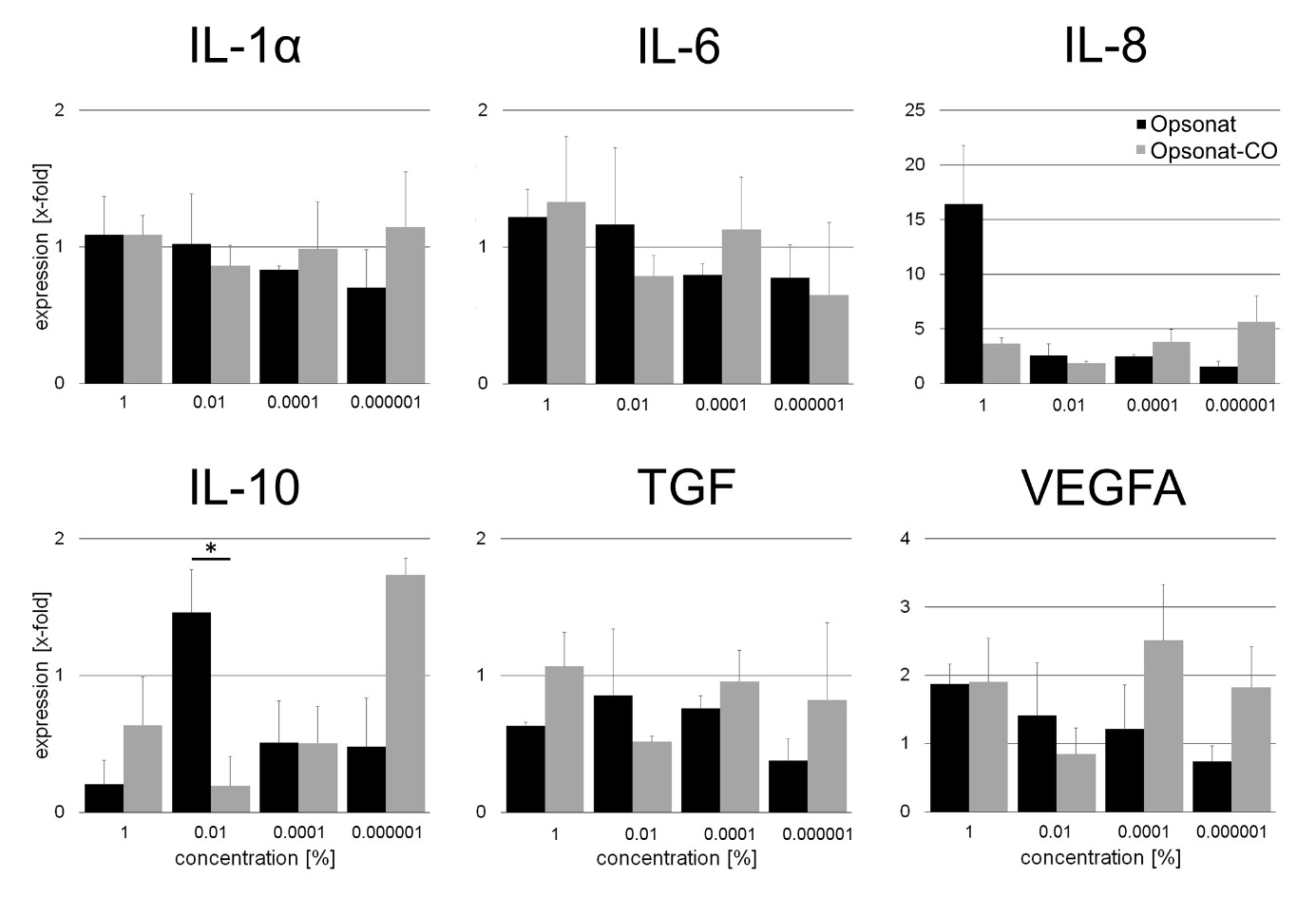

HaCaT cells showed similar wound closure dynamics, reaching >90% closure in ~40 hours with a characteristic sigmoidal migration curve. High (10%) concentrations of the test or carrier substances similarly reduced migration efficiency (50–52 hours). At lower concentrations, Opsonat®-treated HaCaT cells achieved wound closure in 38–44 hours (mean: 40h), while carrier-treated cells closed in 34–44 hours (mean: 39h), compared to 40h in untreated controls (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Wound Healing Assay with BJ.

Figure 4: Wound Healing Assay with BJ.

Relative wound density in percent of a scratch through fibroblastic celllayer incubated with serial dilutions of Opsonat® (A) and carrier substance (B) over time. Images were taken every six hours via Incucyte® S2.

Figure 5: Wound Healing Assay with HaCat.

Figure 5: Wound Healing Assay with HaCat.

Relative wound density in percent of a scratch through keratinocytic celllayer incubated with serial dilutions of Opsonat® (A) and carrier substance (B) over time. Images were taken every six hours via Incucyte® S2.

Gene Expression Analysis

Gene expression data are presented as fold changes relative to untreated controls. In HaCaT keratinocytes, Opsonat® treatment resulted in a consistent upregulation of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines as well as growth factors across all tested concentrations, compared to the carrier control, with fold changes ranging from 1.96 to 3.61. The only exception was IL-10 at 0.01%, which showed a 0.54-fold decrease. Notably, significant upregulation was observed for several genes, including: IL-1α: 1% (2.39-fold, p = 0.0196), 0.01% (1.92-fold, p = 0.0163), 0.000001% (1.69-fold, p = 0.0494). IL-6: 0.01% (2.15-fold, p = 0.0043). IL-8: 0.01% (1.69-fold, p = 0.0329). TGF: 0.01% (2.21-fold, p = 0.0029), 0.0001% (1.91-fold, p = 0.0486), 0.000001% (2.28-fold, p = 0.0302).

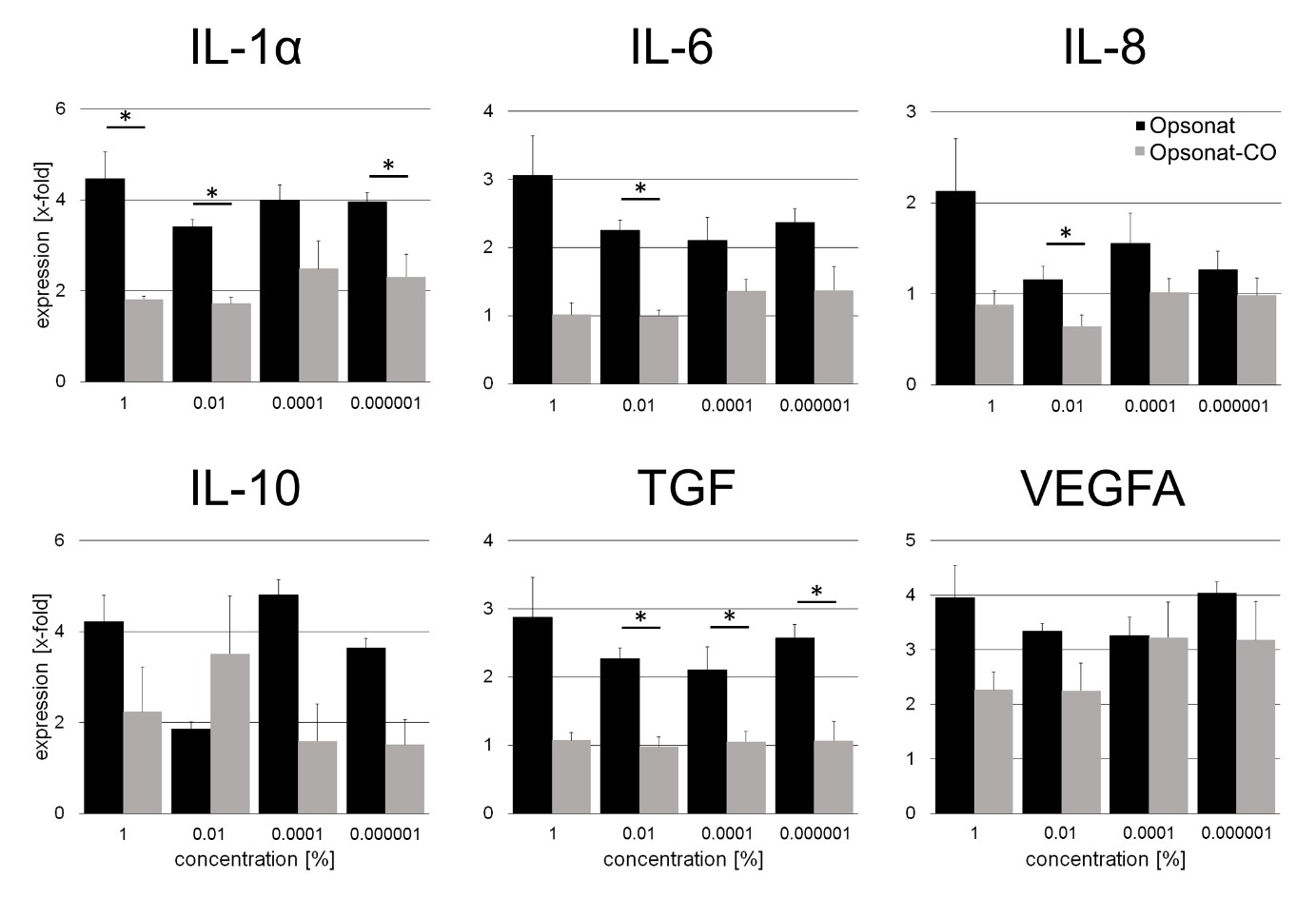

In contrast, BJ fibroblasts showed a more variable response, with both up- and downregulation across genes and concentrations. Most gene inductions were modest (1.00–1.60-fold), except for IL-8 at 1% (4.41-fold) and IL-10 at 0.01%, which was significantly upregulated (5.36-fold, p = 0.0351). Gene suppression ranged from 0.02- to 0.98-fold (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Gene expression of inflammatoric cytokines and growth factors in BJ.

Figure 6: Gene expression of inflammatoric cytokines and growth factors in BJ.

Gene expression as x-fold to untreated control from supernatant after 24 hours of incubation with substances. A p-value < 0.05 was determined as statistically significant (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Gene expression of inflammatoric cytokines and growth factors in HaCat.

Figure 7: Gene expression of inflammatoric cytokines and growth factors in HaCat.

Gene expression as x-fold to untreated control from supernatant after 24 hours of incubation with substances. A p-value < 0.05 was determined as statistically significant.

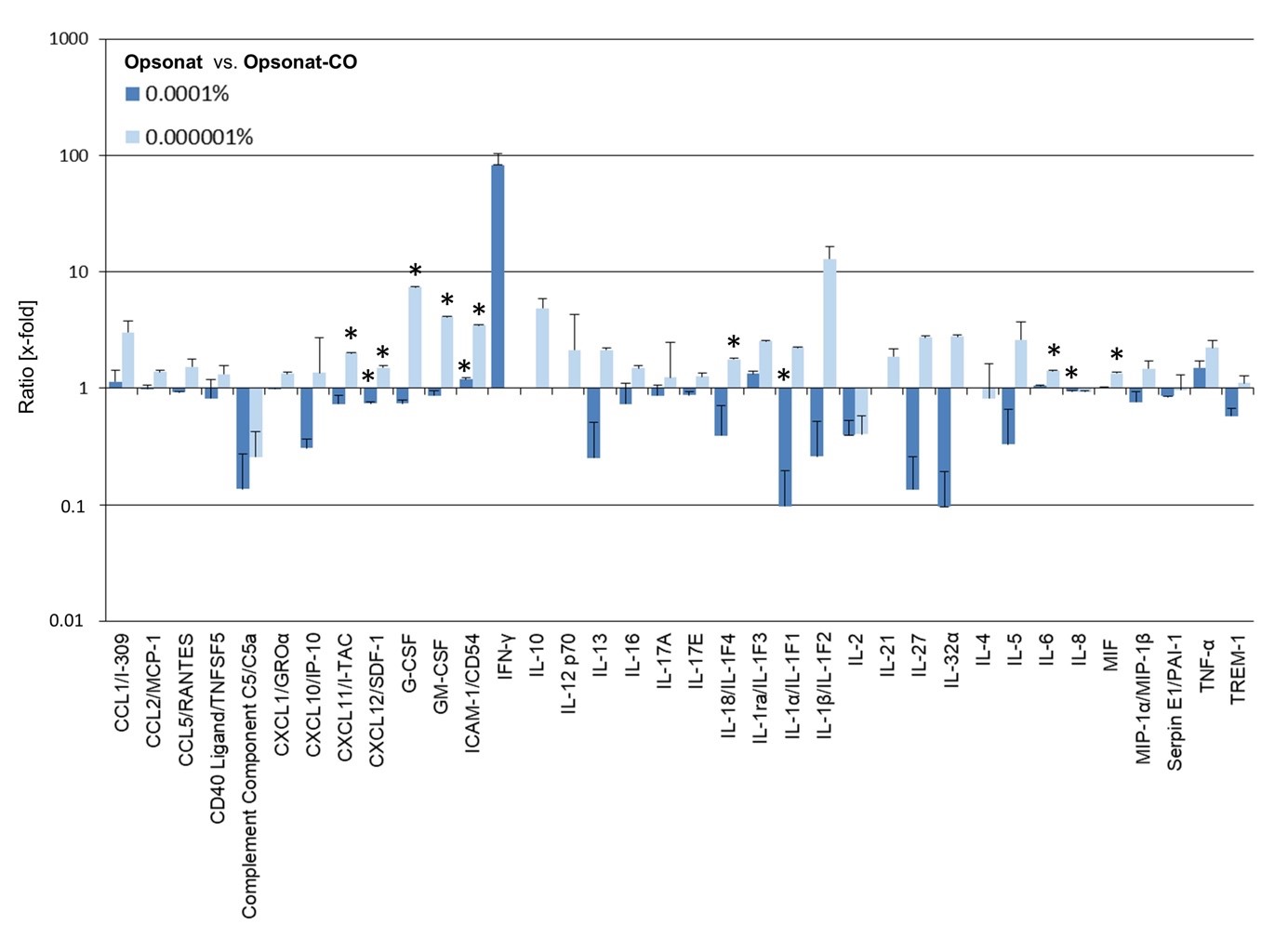

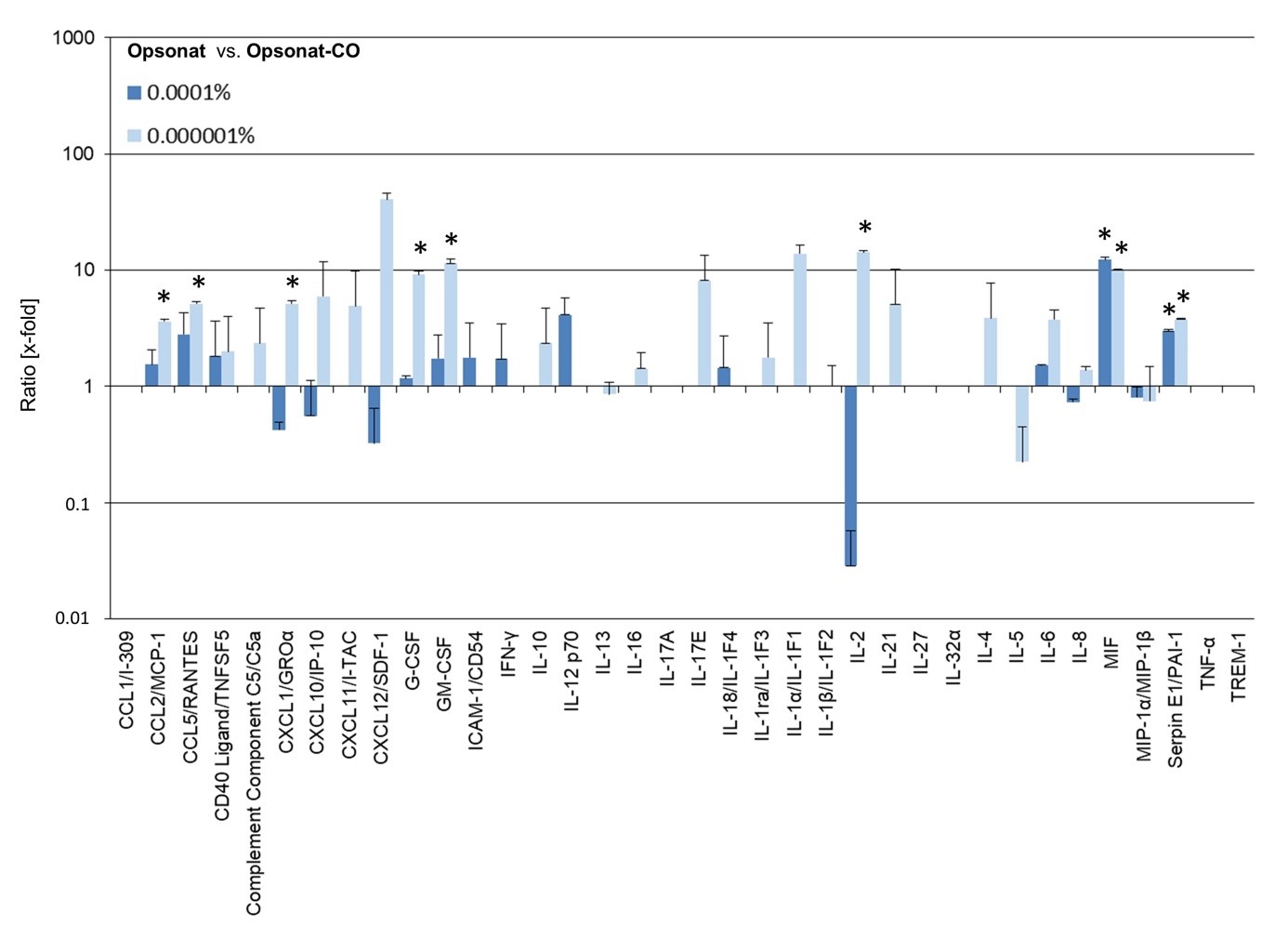

Protein Expression Analysis

Relative protein expression in BJ cells treated with Opsonat® at 0.0001% and 0.000001%, normalized to carrier-treated controls is showen in figure 8. Both concentrations induced increased expression of several proteins, including CCL1/I-309, ICAM-1/CD54, IL-1ra/IL-1F3, IL-6, MIF, and TNF-α, with significant upregulation observed for ICAM-1/CD54 (0.0001%: 1.19-fold, p = 0.047; 0.000001%: 3.49-fold, p = 0.0039), IL-6 (0.000001%: 1.42-fold, p = 0.0493), and MIF (0.000001%: 1.34-fold, p = 0.0190).

In contrast, expression of Complement Component C5/C5a, IL-2, and Serpin E1/PAI-1 was generally inhibited, with IL-8 significantly reduced at 0.0001% (0.94-fold, p = 0.0205).

Most proteins showed induction at 0.000001% but repression at 0.0001%, including CCL2/MCP-1, CCL5/RANTES, CD40 Ligand/TNFSF5, CXCL1/GROα, CXCL10/IP-10, CXCL11/I-TAC (0.000001%: 1.99-fold, p = 0.0359), CXCL12/SDF-1 (0.0001%: 0.74-fold, p = 0.0243; 0.000001%: 1.50-fold, p = 0.0239), G-CSF (0.000001%: 7.44-fold, p = 0.0001), GM-CSF (0.000001%: 4.08-fold, p = 0.0103), IL-18/IL-1F4 (0.000001%: 1.76-fold, p = 0.0407), and others. Notably, IL-1α/IL-1F1 was strongly suppressed at 0.0001% (0.09-fold, p = 0.0232).

For some cytokines (e.g., IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-21), expression was detectable only at one concentration, with IL-10 and IL-12p70 elevated at 0.000001%, and IFN-γ showing a marked 82-fold increase at 0.0001%. A significant decrease was observed for IL-4 at 0.000001% (Figure 9).

Figure 8: Protein expression of cytokines in BJ.

Figure 8: Protein expression of cytokines in BJ.

Protein expression with Opsonat® treated BJs as expression ratio (x-fold to carrier substance treated cells). A P-value Protein expression in HaCaT cells treated with Opsonat® at 0.0001% and 0.000001% showed significant upregulation compared to carrier controls. Notable increases were observed in: CCL2/MCP-1 (0.000001%: 3.61-fold, p = 0.0311), CCL5/RANTES (0.000001%: 5.14-fold, p = 0.0091), G-CSF (0.000001%: 9.21-fold, p = 0.0208), GM-CSF (0.000001%: 11.39-fold, p = 0.0174), MIF (0.0001%: 12.29-fold, p = 0.0188; 0.000001%: 9.95-fold, p = 0.0061), Serpin E1/PAI-1 (0.0001%: 2.98-fold, p = 0.0084; 0.000001%: 3.76-fold, p = 0.0204), IL-6, CD40 Ligand/TNFSF5, and others (non-significant trends). Only MIP-1α/MIP-1β showed a consistent reduction in expression.

Several cytokines displayed a dose-dependent response, with prominent induction at 0.000001%, including CXCL1/GROα (5.13-fold, p = 0.0318), CXCL10/IP-10, CXCL12/SDF-1, IL-2 (14.19-fold, p = 0.0165), and IL-8.

Due to technical limitations or low expression levels, protein ratios could not be calculated for CCL1/I-309, IL-17A, IL-27, IL-32α, TNF-α, and TREM-1. Select proteins showed concentration-specific expression increases: Only at 0.0001%: ICAM-1/CD54, IFN-γ, IL-12p70, IL-18/IL-1F4. Only at 0.000001%: CXCL11/I-TAC, IL-10, IL-16, IL-17E, IL-1α/IL-1F1, IL-1β/IL-1F2, IL-21, IL-4. In contrast, C5/C5a, IL-13, and IL-5 were downregulated at 0.000001%.

Figure 9: Protein expression of cytokines in HaCat.

Figure 9: Protein expression of cytokines in HaCat.

Protein expression with Opsonat® treated BJs as expression ratio (x-fold to carrier substance treated cells). A p-value < 0.05 was determined as statistically significant.

Discussion

This study examined the regenerative potential of a complex plant-based formulation using in vitro skin models. In contrast to highly diluted homeopathic preparations, the tested remedy contains quantifiable active compounds (MT–D7), supporting the likelihood of pharmacological activity. Gene and protein expression data indicate distinct cellular responses relevant to tissue repair [20]. One of the active components is Bellis perennis (Asteraceae), a perennial medicinal plant native to Europe and traditionally used for its wound-healing and anti-inflammatory properties [18]. The traditional use of Bellis perennis for wound healing is supported by preclinical data; Karakas et al., significantly enhanced wound closure in rats treated with a hydrophilic Bellis perennis extract ointment compared to controls [21]. Morikawa et al., further demonstrated that Bellis perennis extract enhances collagen synthesis in human dermal fibroblasts, an effect also attributed to isolated saponins from the extract [22]. The wound-healing potential of saponins is well established in the scientific literature [15,22,23]. In addition to saponins, flavonoids are key bioactive constituents of Bellis perennis, contributing to its therapeutic effects. They have been shown to support wound healing and positively influence bone metabolism in both in vitro and in vivo models [12,17,19]. Karic et al., demonstrated that commercial Bellis perennis extract possesses notable antioxidant activity, showing strong radical-scavenging capacity and effective reducing power compared to ascorbic acid [24].

BJ and HaCaT cells are well-established in vitro models for studying tissue regeneration. Although their immortalized nature introduces genetic deviations from primary cells, they provide a reproducible and ethically viable platform for initial substance screening. Their phenotype closely resembles that of primary cells. In this study, neither the test substance nor the carrier exhibited cytotoxicity in fibroblasts or keratinocytes. Cell viability and proliferation remained unaffected across all assays (MTT, CTG, BrdU), (Figures 5 & 6).

In the wound healing assay, neither the test substance nor the carrier notably affected cell migration (Figures 7 & 8). The in vitro WHA offers a standardized approach to evaluate wound healing-related processes, particularly cell migration and proliferation. However, it represents a simplified model with limited reproducibility and does not fully capture the complexity of in vivo wound repair [25]. However, these limitations were mitigated by using a standardized protocol with the IncuCyte® system and a large sample size. Both BJ and HaCaT cells achieved over 90% wound closure across treatments. In BJ cells, the test substance at 0.1% to 0.0001% concentrations initially reduced wound density on day one, whereas the carrier increased it. By day two, wound densities matched untreated controls. This suggests a concentration- and cell type-dependent delayed yet effective healing response. The initial lack of accelerated closure may support a more regulated and stable repair process. Further analyses beyond BrdU and wound healing assays are necessary to clarify effects on proliferation and migration. Additionally, in vivo studies are needed to confirm clinical relevance. Notably, ethanol concentrations above 2%—far exceeding recommended doses—induced cytotoxicity, antiproliferative effects, and delayed healing in both cell lines, consistent with previous reports [26]. The reduced wound density observed at 1% concentrations of both test and carrier substances in HaCaT and BJ cells may reflect residual ethanol effects. A processing delay between plates—test substance plates analyzed before carrier plates—limits direct comparison precision.Gene expression analysis revealed early molecular responses not captured by functional assays. HaCaT cells showed consistent upregulation of pro- inflammatory genes (IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, TGF, VEGFA) across concentrations, with significant changes; only IL-10 at 0.01% was an outlier. This suggests a stimulatory effect on keratinocyte inflammatory pathways. BJ cells exhibited mixed gene regulation, with general suppression except for significant IL-8 upregulation at 1% and IL-10 at 0.01%. The data imply concentration-dependent modulation by active compounds. At 1%, the remedy may provoke a pro-inflammatory response, recruiting neutrophils and inducing cytokine release via IL-8, potentially enhancing wound healing through immune activation, angiogenesis, and tissue regeneration [27]. Additionally, the interactions between the individual gene expressions must be taken into account. For example, inhibition of IL-6 expression by IL-10—and vice versa—has been well documented [28]. A strict classification into pro- or anti-inflammatory effects is outdated. Cytokine functions depend on concentration, cell type, signaling pathways, timing, sequence, and specific experimental conditions, reflecting the complexity of regulatory networks [7]. Consequently, simultaneous upregulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines can occur, reflecting the dynamic regulation of immune responses [8,18]. Souza de Carvalho et al., reported that treatment with 1% Bellis perennis extract attenuated the UVA-induced overexpression of IL-6 in HaCaT cells, suggesting a potential anti-inflammatory effect of the extract under oxidative stress conditions.

Changes in gene expression, measured as mRNA levels via qPCR, do not always directly translate into protein synthesis, which ultimately affects cellular function. While mRNA abundance often correlates with protein levels, discrepancies are common due to temporal differences between transcription and translation, as well as post-transcriptional regulation by miRNAs and siRNAs. The proteome array assessed key inflammatory proteins, some corresponding to genes analyzed by qPCR (e.g., IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10), highlighting such regulatory complexities [27]. Moreover, variations in incubation time with the test substance (e.g., 48 hours) prior to conducting the proteome array could also influence the observed outcomes.

Limitations of this study include the use of only two cell lines, which excludes interactions with other cell types, and inherent in vitro restrictions such as lack of bioavailability and uptake data. The study design does not identify which specific active compounds mediate the effects, as the focus was on the complete commercial formulation. Future research should isolate bioactive components and include time-course analyses to clarify gene-protein expression dynamics. Additionally, increasing sample size would improve statistical robustness.

Conclusion

This study employed in vitro models to evaluate a plant-based remedy’s effects on tissue regeneration. Results showed bioactivity with modulation of cell viability, proliferation, wound healing, and gene and protein expression, indicating potential immunomodulating influence on inflammatory responses. However, the clinical relevance of these findings remains unclear due to complex underlying mechanisms. Further research is required to elucidate the impact on physiological tissue regeneration.

Acknowledgement

All experiments were conducted by VFS, SAF and MS in the Andreas Wentzensen Research Institute, BG Trauma Center Ludwigshafen, Rhine, Ludwig-Guttmann-Str.13, D-67071 Ludwigshafen, Germany.

Declarations

Statement of Ethics: The cell lines used in this study were obtained from ATCC®. Ethical approval for the use of this is not required in accordance with national guidelines.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This work was financially supported by PEKANA Naturheilmittel GmbH (Kißlegg, Germany)

Author’s Contributions

All experiments were conducted by VFS, SAF and MS in the Andreas Wentzensen Research Institute, BG Clinic Ludwigshafen, Ludwig-Guttmann-Str.13, 67071 Ludwigshafen, Germany.

VFS, SAF, LH and MS have performed data analysis and interpretation, VFS prepared the manuscript. SAF, MS, LH and critically reviewed the manuscript and contributed intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Ibrahim N', Wong SK, Mohamed IN, Mohamed N, Chin KY, et al. (2018) Wound Healing Properties of Selected Natural Products. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15: 2360.

- Li J, Chen J, Kirsner R (2007) Pathophysiology of acute wound healing. Clin Dermatol 25: 9-18.

- Ahlers JMD, Falckenhayn C, Holzscheck N, Solé-Boldo L, Schütz S, et al. (2021) Single-Cell RNA Profiling of Human Skin Reveals Age-Related Loss of Dermal Sheath Cells and Their Contribution to a Juvenile Phenotype. Front Genet 12: 797747.

- Murphy K, Weaver C (2018) Janeway Immunologie. Springer, Berlin, Germany.

- Geha RS, Notarangelo L (2016) Case Studies in Immunology: A Clinical Companion. Garland Science, Taylor & Francies Group, USA.

- Cavaillon JM (2001) Pro- versus anti-inflammatory cytokines: myth or reality. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 47: 695-702.

- Cicchese JM, Evans S, Hult C, Joslyn LR, Wessler T, et al. (2018) Dynamic balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory signals controls disease and limits pathology. Immunol Rev 285: 147-167.

- Grosskopf A, Simm A (2022) Aging of the immune system. Z Gerontol Geriatr 55: 553-557.

- Sharma A, Shankar R, Yadav AK, Pratap A, Ansari MA, et al. (2024) Burden of Chronic Nonhealing Wounds: An Overview of the Worldwide Humanistic and Economic Burden to the Healthcare System. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2024: 15347346241246339.

- Adhikary S, Choudhary D, Ahmad N, Karvande A, Kumar A, et al. (2018) Dietary flavonoid kaempferol inhibits glucocorticoid-induced bone loss by promoting osteoblast survival. Nutrition 53: 64-76.

- Carvalho MTB, Araujo-Filho HG, Barreto AS, Quintans-Junior LJ, Quintans JSS, et al. (2021) Wound healing properties of flavonoids: A systematic review highlighting the mechanisms of action. Phytomedicine, 90:153636.

- Du Y, Chen W, Li Y, Liang D, Liu G (2023) Study on the regulatory effect of Panax notoginseng saponins combined with bone mesenchymal stem cell transplantation on IRAK1/TRAF6-NF-κB pathway in patients with diabetic cutaneous ulcers. J Orthop Surg Res 18: 80.

- Kim YS, Cho IH, Jeong MJ, Jeong SJ, Nah SY, et al. (2011) Therapeutic effect of total ginseng saponin on skin wound healing. J Ginseng Res 35: 360-367.

- Men SY, Huo QL, Shi L, Yan Y, Yang CC, et al. (2020) Panax notoginseng saponins promotes cutaneous wound healing and suppresses scar formation in mice. J Cosmet Dermatol 19: 529-534.

- Shou D, Zhang Y, Shen L, Zheng R, Huang X, et al. (2017) Flavonoids of Herba Epimedii Enhances Bone Repair in a Rabbit Model of Chronic Osteomyelitis During Post-infection Treatment and Stimulates Osteoblast Proliferation in Vitro. Phytother Res 31: 330-339.

- Zulkefli N, Zahari CNMC, Sayuti NH, Kamarudin AA, Saad N, et al. (2023) Flavonoids as Potential Wound-Healing Molecules: Emphasis on Pathways Perspective. Int J Mol Sci 24: 4607.

- Al-Qahtani AA, Alhamlan FS, Al-Qahtani AA (2024) Pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Interleukins in Infectious Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Trop Med Infect Dis 9: 13.

- Albien AL, Stark TD (2023) (Bio) active Compounds in Daisy Flower (Bellis perennis). Molecules 28: 7716.

- Avato P, Argentieri MP (2019) Quality Assessment of Commercial Spagyric Tinctures of Harpagophytum procumbens and Their Antioxidant Properties. Molecules 24: 2251.

- Karakas FP, Karakas A, Boran C, Turker AU, Yalcin FN, et al. (2012) The evaluation of topical administration of Bellis perennis fraction on circular excision wound healing in Wistar albino rats. Pharm Biol 50: 1031-1037.

- Morikawa T, Ninomiya K, Takamori Y, Nishida E, Yasue M, et al. (2015) Oleanane-type triterpene saponins with collagen synthesis-promoting activity from the flowers of Bellis perennis. Phytochemistry 116: 203-212.

- Du Y, Chen W, Li Y, Liang D, Liu G (2023) Study on the regulatory effect of Panax notoginseng saponins combined with bone mesenchymal stem cell transplantation on IRAK1/TRAF6-NF-kappaB pathway in patients with diabetic cutaneous ulcers. J Orthop Surg Res 18: 80.

- Karic E, Horozic E, Pilipovic S, Dautovic E, Ibiševic M, et al. (2023) Tyrosinase inhibition,antioxidant and antibacterial activity of commercial daisy extract (Bellis perennis). Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International 35: 13-19.

- Grada A, Otero-Vinas M, Prieto-Castrillo F, Obagi Z, Falanga V (2017) Research Techniques Made Simple: Analysis of Collective Cell Migration Using the Wound Healing Assay. J Invest Dermatol 137: 11-16.

- Collaborators GBDA (2018) Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 392: 1015-1035.

- Schruefer R, Lutze N, Schymeinsky J, Walzog B (2005) Human neutrophils promote angiogenesis by a paracrine feedforward mechanism involving endothelial interleukin-8. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: 1186-1192.

- Moore KW, Malefyt RW, Coffman RL, O'Garra A (2001) Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol 19: 683-765.

Citation: Struckmann VF, Allouch-Fey S, Harhaus L, Schulte M (2025) Investigating the Impact of a Plant-Based Remedy on Tissue Regeneration in Human Fibroblasts and Keratinocytes: An In-vitro Analysis. HSOA J Altern Complement Integr Med 11: 665.

Copyright: © 2025 Victoria Franziska Struckmann, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.