Is It Really A Neuroretinitis? Working Together To Find the Etiology

*Corresponding Author(s):

Ana Luisa De CarvalhoHospital De Braga, Paediatrics Department, Braga, Portugal

Email:a.luisacarvalho@live.com.pt

Abstract

Neuroretinitis is a rare ophthalmic disease characterized by inflammation of the optic disc and the neurosensory retina. It was classically described as a triad of unilateral vision loss, optic disc swelling and macular star. The diagnosis is clinical, through the observation of unilateral optic disc edema and a macular star. The recognition of the diagnosis is crucial since, although it may be idiopathic and self-limited, severe conditions may be on the basis of the phenotype, requiring prompt treatment. However, neurorretinitis can also mimic same different ophthalmic etiologies who deserve a different approach. We present a case of a seven years-old girl with a suspected neurorretinitis, that was not confirmed in the further follow-up, leading to a different diagnosis.

This case highlights the wide spectrum differential diagnosis of neurorretinitis and the importance to both ophthalmologists and pediatricians/pediatric rheumatologists work together to better characterize the findings on clinical history and physical examination and thus establish the correct diagnosis and optimal treatment.

Keywords

Optic disc edema; Optic Structural Diseases; Papilledema; Retinal Diseases; Retinitis

Introduction

Neuroretinitis is a rare ophthalmologic disease, characterized by inflammation of the optic disc and the neurosensory retina. It has multiple causes and both ophthalmologists and pediatricians should work together to establish the etiology, as it has implications on treatment and follow-up.

Neuroretinitis was classically described as a triad of unilateral vision loss, optic disc swelling and macular star. It was firstly denominated “idiopathic stellate maculopathy” by Leber in 1916 [1], the designation being updated to neuroretinitis because of the findings of fluid leakage from the optic disc [2].

It consists of inflammation of the optic disc vasculature with increased vessel permeability, leading to leakage of lipidic exudate to the outer plexiform and nuclear layers of the peripapillary retina, forming the characteristic macular star pattern. The optic disc vasculitis mechanism is unknown. Most cases are preceded by flu-like symptoms, so it’s thought to have a viral etiology by direct invasion of the optic nerve as well as an immune-mediated response to the virus [2].

According to the etiology, it is classified as infectious or non-infectious. Most cases are infectious, with cat scratch disease being the most frequent cause [2,3], occurring predominantly in children. Non-infectious neuroretinits is an inflammatory condition which can be classified as idiopathic whenever a systemic inflammatory disease cannot be identified [2,4]. There is a number of inflammatory diseases associated with neuroretinitis such as sarcoidosis, Behçet´s syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease [2,4-6]. The diagnosis is clinical, through the observation of unilateral optic disc edema and a macular star [1,2,4,5].

The differential diagnosis must be established with other causes of macular star and disc edema, such as hypertensive retinopathy, diabetic optic neuropathy, disc tumors (like angioma and melanoma) and ischemic optic neuropathy. The presence of bilateral vision loss and ocular pain should lead to alternate diagnoses, like optic neuritis [4].

Case Description

Previously healthy seven-year-old girl referred to a tertiary ophthalmology center for evaluation and treatment of a suspected neuroretinitis, incidentally diagnosed in a routine ophthalmology outpatient clinic. The presentation was asymptomatic, with left eye (LE) disc swelling associated with retinal exudates in a macular-star configuration. The patient had already been submitted to a complete workout, including serologic and imaging evaluation. Serologies for Bartonella, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and type 1 and 2 herpes simplex virus, Borrelia and toxocariasis were all negative. The immunologic study, including Antinuclear Antibodies, Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies, anti-phospholipid antibodies, Rheumatoid Factor, Human Leucocyte Antigen B27 was negative and the full blood count, renal and hepatic profiles were normal, as well as angiotensin-converting enzyme levels. Cerebral and orbital magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was unremarkable. Despite negative serologies, and given the higher incidence, neuroretinitis caused by Bartonella had been considered likely and the patient was started empirical antibacterial therapy (sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim 56 mg/Kg plus rifampicin 10mg/Kg per day) and corticotherapy (intravenous methylprednisolone 15,4mg/Kg twice day). No improvement was achieved and the patient was referred to our center for further investigation and therapy.

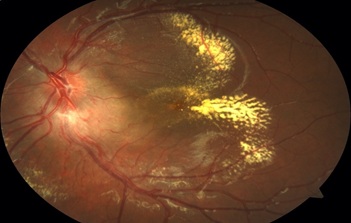

At our evaluation, the best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/20 on the right eye (RE) and 20/63 on the LE. The anterior segment was unremarkable in both eyes and intra-ocular pressure (iCareÒ tonometer) was 14 mmHg bilaterally. RE fundoscopy was normal, while an elevated and ill-defined optic disc associated with retinal exudates around the major vessel arcades were evident on the LE (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Left eye retinography showing ill-defined optic disc borders without evident vessel exsudation. Retina exsudates along vascular arcades in a pseudo-macular star configuration.

Figure 1: Left eye retinography showing ill-defined optic disc borders without evident vessel exsudation. Retina exsudates along vascular arcades in a pseudo-macular star configuration.

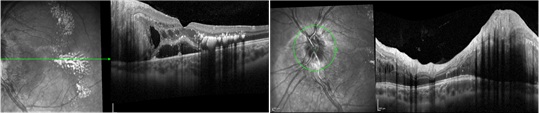

Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT) showed an increase in the retinal nerve fiber layer of the LE optic disc and cystic macular edema with hyperreflective exudates in the external layers of the retina (figure 2).

Figure 2: Left eye macular and optic disc Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) scans. Evidence of cystic and subretinal macular edema with exudates predominantly in the external retinal layers. Evidence of Increased and not uniform thickness of the optic disc.

Figure 2: Left eye macular and optic disc Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) scans. Evidence of cystic and subretinal macular edema with exudates predominantly in the external retinal layers. Evidence of Increased and not uniform thickness of the optic disc.

Neuroretinitis seemed unlikely at this point and a therapeutic trial with oral steroids (deflazacort 1 mg/kg id) was performed to assess for an inflammatory etiology. No structural or functional changes were observed afterwards, thus excluding an inflammatory mechanism, and mandating a review of the diagnostic hypothesis.

Fluorescein angiography was performed showing peripapillary contrast diffusion and late impregnation, more marked in the lower quadrants, hinting at a longstanding condition (Figure 3). The exclusion of an inflammatory etiology allied to the absence of symptoms and the chronic structural changes suggested a structural lesion of the optic nerve as a more likely diagnosis.

Figure 3: Wide-field fluoresceine angiography image evidencing peripapillary late diffusion and impregnation without other relevant signs.

Figure 3: Wide-field fluoresceine angiography image evidencing peripapillary late diffusion and impregnation without other relevant signs.

The patient was subsequently referred for further investigations to exclude glial tumors potentially related to phacomatoses or retinal vascular tumors suggestive of Von Hippen Lindau Disease, awaiting genetic study results.

Discussion

This case reinforces that rare non-inflammatory conditions may present with similar clinical findings of neurorretinitis, requiring a multidisciplinary effort in its differential diagnosis.

Despite its different etiologies, neurorretinitis has similar findings and progression [5]. The fundoscopic findings are similar, except for the presence of multifocal white retinal lesions that are characteristic of cat scratch disease and rare on idiopathic neurorretinitis. Another difference reported is that the typical macular star may not be visible on recurrent idiopathic episodes [2]. In cat scratch disease-associated neuroretinitis the visual loss is due to a macular disfunction, whereas in idiopathic recurrent neuroretinitis it is due to macular disfunction as well as optic nerve vasculitis [2]. Visual loss severity is higher in recurrent neuroretinitis and vision recovery may be limited [6].

A detailed clinical history should be obtained allied to complete physical examination and laboratory workup [2-5], including serologic tests for Bartonella, Lyme disease, toxoplasmosis, histoplasmosis, brucellosis, Chlamydia, syphilis, HIV, B and C hepatitis, tuberculosis and blood cultures should also be considered [5]. The prognosis is good as most cases resolve without treatment and recurrent episodes are rare. Specific treatment depends on the cause, with possibility of antibiotics in cat scratch disease-associated neuroretinitis and in recurrent idiopathic cases [2,4].

The absence of a cause should not rule out neurorretinitis, since idiopathic forms may be present, although these are less common in children [2]. A distinct disease's course, however, without spontaneous improvement or response to the established medication, should prompt additional screening.

Our case illustrates an early suspicion of neurorretinitis with an ophthalmologic examination that was compatible but did not follow the usual course of the illness.

Regardless of the cause, neurorretinitis is an inflammatory illness. As a result, even if the condition is idiopathic, a course of corticotherapy should result in an improvement in signs and symptoms. The lack of remission with therapy, together with auxiliary examinations revealing structural permanent abnormalities, prompted our team to seek a new diagnosis. The SD-OCT and Fluoresceine Angiography were crucial tests since they revealed signs more likely connected to optic nerve structural problems. A neurocutaneous condition is now suspected, and the patient is being monitored on a regular basis. The knowledge of this diagnosis was critical in directing the patient's follow-up to the potential sequelae of phacomatosis and other neurocutaneous disorders. These syndromes may affect the brain, spinal cord and other organs with a lifelong risk of growing tumors in these areas [7,8]. Therefore, the establishment of this diagnosis was important to the assure the correct follow-up.

Due to the large spectrum of etiologies and differential diagnosis of neurorretinitis, it is important that both ophthalmologists and pediatricians/pediatric rheumatologists work together to better characterize the findings on clinical history and physical examination and thus establish the correct diagnosis and optimal treatment in every complex and challenging cases as the one here presented.

Acknowledgments

None

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Dreyer RF, Hopen G, Gass JD, Smith JL (1984) Leber's idiopathic stellate neuroretinitis. Arch Ophthalmol 102: 1140-1145.

- Abdelhakim A, Rasool N (2018) Neuroretinitis: A review. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 29: 514-519.

- Suhler EB, Lauer AK, Rosenbaum JT (2000) Prevalence of serologic evidence of cat scratch disease in patients with neuroretinitis. Ophthalmology 107: 871-876.

- Purvin V, Sundaram S, Kawasaki A (2011) Neuroretinitis: Review of the literature and new observations. J Neuroophthalmol 31: 58-68.

- Ray S, Gragoudas E (2001) Neuroretinitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin 41: 83-102.

- Rabina G, Amarilyo G, Zur D, Harel L, Habot-Wilner Z (2020) Recurrent Neuroretinitis: A Unique Presentation of Behçet's Disease in a Child. Case Rep Ophthalmol 11: 516-522.

- Troullioud Lucas AG, Mendez MD (2023) Neurocutaneous Syndromes. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing

- Ruggieri M, Polizzi A, Marceca GP, Catanzaro S, Praticò AD, et al. (2020) Introduction to phacomatoses (neurocutaneous disorders) in childhood. Childs Nerv Syst 36: 2229-2268.

Citation: Carvalho AL, Moleiro AF, Gomes M, Cardoso I, Pereira MO, et al. (2023) Is It Really A Neuroretinitis? Working Together To Find the Etiology. J Med Stud Res 5: 024.

Copyright: © 2023 Ana Luisa de Carvalho, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.