Lichen Sclerosis Involving Vagina and Cervix

*Corresponding Author(s):

Mohsen HassanDepartment Of Obstetrics And Gynaecology, King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

Tel:+44 1689863000,

Email:mohsensmh@hotmail.com

Abstract

Background: Lichen Sclerosus (LS) is commonly a disease of the vulva usually seen in postmenopausal women. It presents as an atrophic white patchy area in a figure of 8 pattern. Fissuring is also commonly seen because of skin fragility. It is diagnosed by history and clinical assessment but usually confirmed with a biopsy. There is no cure for LS. The mainstay of treatment is potent topical steroids and in some cases oral immunosuppressive medicines may also be used. It is important to acknowledge the role of laser surgery in treating the sequel of scarring secondary to LS. Because LS is associated with increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma in women with genital involvement, it is important for those affected to have lifelong screening examinations as well as continued treatment to keep the disorder under control. Only six cases of vaginal LS, but no cases of cervical LS exist in the literature.

Case: The authors present a case of a postmenopausal lady presenting with a 30 year history of prolapse and a urinary tract infection. Examination revealed, 3rd degree utero-vaginal prolapse with widespread whitish discoloration of anterior, posterior and lateral vaginal walls, which also included the cervix. After counseling the patient and presenting her with the options for treatment, she chose to have the gellhorn pessary inserted in the outpatient clinic. Vaginal and cervical biopsy was taken under local anesthesia and histology confirmed LS. Patient was followed up in clinic and prescribed steroids.

Conclusion: LS involving the vagina and cervix is a rare occurrence, unlike lichen planus, which can present in the vagina. Long term untreated genital prolapse may have a role in the development. As the occurrence of this condition is rare, each case should be treated individually and ideally after discussion in MDT meeting.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Lichen Sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease of unknown and poorly understood etiology. It was first described by Hallopeau in 1887 as an atrophic form of lichen planus, although now it is believed to represent a separate disease entity [1]. Autoimmunity likely has a role in the pathogenesis, possibly due to genetic, hormonal, irritant and/or infectious factors (or a combination of these factors). Over the years, LS has gone by multiple names, including “circumscribed scleroderma,” “kraurosis vulvae,” “leukoplakic vulvitis,” “hypoplastic vulvar dystrophy,” “lichen sclerosus et atrophicus,” and (when seen in male patients) “balanitis xerotica obliterans” [2]. LS most commonly affects the anogenital skin and is seen more frequently among women than men. Lichen Sclerosis can affect all age groups with a higher incidence of onset during early childhood and after menopause [1-3]. LS can be asymptomatic in some patients; however, in others, it can result in severe itching, burning, dyspareunia and irreversible anatomical changes with the potential to interfere with voiding and sexual function [4].

CASE

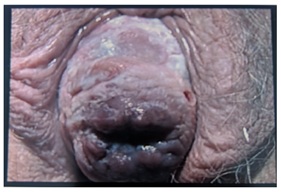

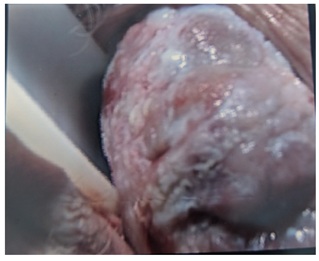

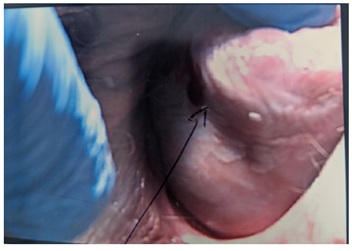

We report a case presenting as vaginal and cervical LS. There have been six cases of vaginal LS but no reported cases of cervical LS. This was case with a 30 year history of prolapse. Examination revealed, 3rd degree utero-vaginal prolapse with widespread whitish discoloration of anterior, posterior and lateral vaginal walls, which also included the cervix (Figures 1-5). There was no evidence of an underlying autoimmune condition or any significant medical/surgical history. Biopsy confirmed lichen sclerosis due to the evidence of stratified squamous epithelium exhibiting hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis and irregular acanthosis along with an infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils in the sub-epithelium. Focally the sub-epithelium showed prominent hyalinisation of collagen.

Figure 1: Complete prolapse of the uterus, protruding outside the introitus. The cervical OS can be seen clearly. Patchy white surface of mucosa must be observed.

Figure 1: Complete prolapse of the uterus, protruding outside the introitus. The cervical OS can be seen clearly. Patchy white surface of mucosa must be observed.

Figure 2: LS patches seen surrounding the cervical OS.

Figure 2: LS patches seen surrounding the cervical OS.

Figure 3: LS patches extensively spread on cervix.

Figure 3: LS patches extensively spread on cervix.

Figure 4: LS patches running along the length of the cervix.

Figure 4: LS patches running along the length of the cervix.

Figure 5: LS over the lateral surface of the uterine wall.

Figure 5: LS over the lateral surface of the uterine wall.

Patient chose to have a gellhorn pessary inserted to ease the symptoms of the prolapse and was treated with topical steroids. She was followed up in the outpatient clinic after 3 to 4 months to assess the results of the topical steroids. She was also counseled about the surgical management for her uetro-vaginal prolapse. The patient was given informed choice and was given time to consider the options. The benefits of surgical management would entail the following:- 1) Minimizing the risk of changes in the vaginal/cervical mucosa to Squamous cell carcinoma. 2) Treatment of her utero-vaginal prolapse and her urinary symptoms.

DISCUSSION

The underlying cause of LS is not fully understood. The condition is believed to be related to an autoimmune process, in which antibodies mistakenly attack a component of the skin. Other autoimmune conditions are reported to occur more frequently than expected in people with LS [5]. However, no evidence has been identified to support testing for auto-antibodies without a clinical indication according to the RCOG guidelines. Approximately 10% of women with vulval LS will also have non-genital areas of skin affected, [6] and up to 20% may have another autoimmune disease, such as thyroid dysfunction, vitiligo, psoriasis or pernicious anaemia [5,6].

In some cases, LS appears on skin that has been damaged or scarred from previous injury or trauma [7]. Local irritation or trauma seems to play a role in some cases of LS especially in genetically predisposed individuals [8]. The Köbner phenomenon also called the Koebner response or the isomorphic response, attributed to Heinrich Köbner, is the appearance of skin lesions on lines of trauma. The Koebner phenomenon may result from either a linear exposure or irritation [9]. In this case, irritation due to leakage of urine and friction from mass lying outside the vagina. However, the sequence of events leading to the altered fibroblast function, microvascular changes and hyaluronic acid accumulation in the upper dermis is still being researched. The prevalence of vulvar LS in elderly nursing home women in one study was found to be 3% (1 in 30) [10].

Lack of familiarity with the condition and failure to examine the genital skin properly can lead to long delays in diagnosis. The condition characteristically begins as a patch of pallor, with white, waxy and polygonal papules that coalesce into shiny plaques. The skin is thinned and atrophic and shows disruption of its regular architecture. Frequently, erosions and tender fissures in the labial sulci and perianal region occur. In chronic disease, many patients experience progressive scarring of the vulva leading to obliteration and fusion of the labia and the periclitoral structures. The most common symptoms are pruritus, soreness, burning pain, dyspareunia, dysuria, or even constipation [1]. Female genital lesions may be confined to the labia majora but usually involve, and eventually obliterate, the labia minora and stenose the introitus. Often, an hourglass, butterfly, or figure-8 pattern involves the perivaginal and perianal areas, with minimal involvement of the perineum in between. Female genital complications include dyspareunia, urinary obstruction, secondary infection from chronic ulceration, secondary infection related to steroid use and squamous cell carcinoma (rare). Some estimates are as high as 5% for the lifetime risk of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma in patients with LS [11]. There was also an increased risk for vaginal cancer among LS patients [12]. The pathogenesis of LS in development of SCC is unclear, It has been suggested that LS and HPV may not be mutually exclusive but may act as cofactors in SCC pathogenesis [13]. There is a remote theoretical risk that topical corticosteroid use might induce oncogenic HPV [14].

LS may result in significant psychosocial distress and anxiety severely affecting quality of life [15]. Diagnosis of LS may often be made on clinical appearance, and ancillary examinations such as vulvoscopy may help confirm the diagnosis [16]. Biopsy should be performed in doubtful cases and, in follow up, biopsy samples from non-healing ulcerations or masses should be examined to exclude malignant transformation. Skin biopsy (punch biopsy) is the primary study to perform for the diagnosis of LS.

All genital LS cases should be treated, even if asymptomatic, with the goal of preventing scarring and its associated disfigurement, sexual and urinary dysfunction, and its negative impact in quality of life. Lichen sclerosus was historically treated with keratolytic, caustic, or irritating agents including salicylic acid, trichloroacetic acid and thymol [2]. Until the 1950s, various forms of radiotherapy were used for the treatment of lichen sclerosus [17] followed by the systemic application of bismuth [18]. Surgical approaches including vulvectomy, cryosurgery and carbon dioxide laser vaporization have also been advocated as treatment options [19-21]. However, the rates of relapse after these therapeutic approaches were exceedingly high, reaching 85% [22]. Today, topical application of potent corticosteroid ointment is considered the treatment of choice [23]. While calcineurin inhibitors (pimecrolimus or tacrolimus) are reserved for cases of failure. Treatment success is typically evaluated every 3 months when actively modifying the treatment to suit the patient’s compliance.

CONCLUSION

LS of the vagina may be more common than anticipated and hence it is very often under diagnosed or misdiagnosed. Patients who are post-menopausal can often manifest with LS of the vagina due to the atrophic changes that occur during this period. Adding to this, women with pelvic organ laxity may be at a higher risk if vaginal walls are chronically exposed because of prolapse. Gynecologists managing patients with vulvar LS should always rule out vaginal involvement so that vaginal lesions may be diagnosed and followed up appropriately.

REFERENCES

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F (1999) Lichen sclerosus. Lancet 353: 1777-1783.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE (1995) Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 32: 393-416.

- García-Bravo B, Sánchez-Pedreño P, Rodríguez-Pichardo A, Camacho F (1988) Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. A study of 76 cases and their relation to diabetes. J Am Acad Dermatol 19: 482-485.

- Tasker GL, Wojnarowska F (2003) Lichen sclerosus. Clin Exp Dermatol 28: 128-133.

- Oakley A (2016) Lichen sclerosus. DermNet NZ, Hamilton, New Zealand.

- Thorstensen KA, Birenbaum DL (2012) Recognition and management of vulvar dermatologic conditions: Lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, and lichen simplex chronicus. J Midwifery Womens Health 57: 260-275.

- NIAMS (2014) Lichen Sclerosus. NIAMS, Maryland, USA.

- Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias (2010) Koebner phenomenon. Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias.

- Dalziel KL (1995) Effect of lichen sclerosus on sexual function and parturition. J Reprod Med 40: 351-354.

- Bjeki? M, Šipeti? S, Marinkovi? J (2011) Risk factors for genital lichen sclerosus in men. Br J Dermatol 164: 325-329.

- Leibovitz A, Kaplun VV, Saposhnicov N, Habot B (2000) Vulvovaginal examinations in elderly nursing home women residents. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 31: 1-4.

- Jones RW, Sadler L, Grant S, Whineray J, Exeter M, et al. (2004) Clinically identifying women with vulvar lichen sclerosus at increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma: A case-control study. J Reprod Med 49: 808-811.

- Borghi A, Corazza M, Minghetti S, Bianchini E, Virgili A (2016) Dermoscopic Features of Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus in the Setting of a Prospective Cohort of Patients: New Observations. Dermatology 232: 71-77.

- Halonen P, Jakobsson M, Heikinheimo O, Riska A, Gissler M, et al. (2017) Lichen sclerosus and risk of cancer. Int J Cancer 140: 1998-2002.

- Xavier J, Vieira-Baptista P, Moreira A, Portugal R, Beires J, et al. (2017) Vaginal lichen sclerosus: Report of two cases. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 9: 171-173.

- Kiene P, Milde-Langosch K, Löning T (1991) Human papillomavirus infection in vulvar lesions of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Arch Dermatol Res 283: 445-448.

- Gottschalk HR, Cooper ZK (1947) Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with bullous lesions and extensive involvement; report of a case. Arch Derm Syphilol 55: 433-440.

- Feldman FF, Lerner AG (1961) Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Arch Dermatol 83: 705-706.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, Black MM (1988) Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity--a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol 118: 41-46.

- Abramov Y, Elchalal U, Abramov D, Goldfarb A, Schenker JG (1996) Surgical treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: A review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 51: 193-199.

- August PJ, Milward TM (1980) Cryosurgery in the treatment of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus of the vulva. Br J Dermatol 103: 667-670.

- Edwards L (1999) Diseases and disorders of the anogenitalia of females. In: Fitzpatrick TB (ed.). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine (5thedn). McGraw-Hill, New York, USA.

- Dalziel KL, Millard PR, Wojnarowska F (1991) The treatment of vulval lichen sclerosus with a very potent topical steroid (clobetasol propionate 0.05%) cream. Br J Dermatol 124: 461-464.

Citation: Sayed K, Fernandes R, Hassan M (2019) Lichen Sclerosis Involving Vagina and Cervix. J Reprod Med Gynecol Obstet 4: 026.

Copyright: © 2019 Khashia Sayed, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.