Medication Reconciliation and Patient Education at a Primary Care Office in South Florida

*Corresponding Author(s):

Maria Elena NasiffFlorida International University, Florida, United States

Tel:+1 3056090533,

Email:Maria.nasiff79@gmail.com

Abstract

Mediation reconciliation is a process that is crucial for ensuring drug safety among patients who demonstrate low medication adherence. Medication reconciliation at the Primary Care office is achieved by educating patients about the purpose of prescribed medicines, drug-to-drug, and drug-to-food interactions. Besides, patients are consulted about interactions between conventional and complementary and alternative medicine, and the dangers of consuming substances (illicit drugs, alcohol, nicotine) together with prescribed drugs. This approach is planned to be accomplished by means of combining printed medication reconciliation lists followed by open-ended questions included to check patients’ pharmacovigilance and conduct patient engagement. In addition, the innovative approach of the present project is inclusion of patients’ significant others in the process of advancing their treatment adherence. Direct participation of patients and their family member in medication reconciliation is expected to bring significant positive results. This project is valuable for advanced nurse practicing because it demonstrates the new ways to improve nurse-patient interactions, advance communication with patients’ family members and in overall, advance their pharmacovigilance.

Keywords

Adverse drug events; Medication reconciliation; Pharmacovigilance

INTRODUCTION/PROBLEM STATEMENT/SIGNIFICANCE TO NURSING

Drug prescription errors, discrepancies and low treatment adherence result in frequent adverse drug events. The latent issues that stipulate occurrence of adverse drug events should be understood by healthcare providers in order to reduce and anticipate negative consequences. For example, it should be noted that polypharmacy is one of the reasons that increase the probability of discrepancies [1]. This scenario is especially common for older adults diagnosed with one or several chronic conditions, but not willing to follow treatment plan due to poor healthcare literacy, forgetfulness, cultural particularities or other reasons [1,2]. Another reason is the occurrence of drug prescription errors, for instance, doubles prescription or wrong doses, during patients’ transition from one treatment facility to another, as well as during hospital discharge to home [3]. Moreover, due to cultural, financial and other reasons many patients prefer to take complementary and alternative medicine [4]. Using complementary and/or alternative means of treatment can be useful in some cases, but also it can be dangerous because of poorly anticipated interactions between taken substances. Besides, according to Armor et al., [5] and Coletti et al., [6] poor treatment adherence of patients is stipulated by their limited knowledge and understanding of the treatment importance that should be mitigated by adequate therapeutic monitoring, which sometimes is not conducted properly.

Problem statement

Poorly arranged therapeutic monitoring over patients’ treatment adherence stems from insufficient nurse-patient communication, and may cause adverse drugs events. Communication may be complicated by cultural gaps, which complicates the task of increasing patients’ healthcare literacy. As a result, the gap between providers’ expectations of what patients take and their actual treatment behavior widens [7]. The identified problem is prevalent at this particular Primary Care office in South Florida where clients belong to the Hispanic culture who is adults with polypharmacy. To conduct medication reconciliation, healthcare providers should improve nurse-patient relations to be able to increase patient engagement in pharmacovigilance.

Significance to nursing

Patient safety is a priority in the healthcare field. Patient’s poor treatment adherence represents a high risk for danger due to potential adverse drug events. In this regard, healthcare providers (Nurse Practitioners) have an important role in combating this problem. Hispanic adults in South Florida constitute a minority population that can be referred to as vulnerable population whose needs should be advocated by healthcare providers. Specifically, this population is observed to demonstrate low treatment adherence due to poor healthcare literacy and limited understanding of prescriptions, as well as may be reluctant to follow treatment plan due to cultural beliefs. Under such circumstances, the task of nurse practitioners is to identify and deploy effective intervention aimed at advancing communication with patients and their family members, as well as increase their participation and involvement in the process of medication reconciliation.

SUMMARY OF THE LITERATURE/EVIDENCE RELATED TO THE CLINICAL QUESTION

Hispanic Population is the largest and one of the fastest-growing minority groups in South Florida. It is known that rates of Hispanics with complex medical conditions (DM, HTN, CVA…) are high compared to other populations. At the same time, studies show that Hispanics have lower medication adherence [8]. These factors can be related to many reasons including lack of literacy and lack of understanding on their medical treatments and medications. According to Sobel et al., [9] Hispanic population responds better when there is “Connectedness” between nurse practitioner patient and family member as the central phenomenon. Family involvement is of great importance in this population. Many patients in this population tend to delay care or cancel appointments due to having to wait for a family member to be with them when visiting doctors and receiving education. In order to develop connectedness, Practitioner has to understand the cultural part of this population. In many instances, the lack of cultural competence between practitioners - patient inhibits patients to believe in the treatment and benefits of medications ending up in lack of adherence. On the other side, Green et al., [8] reports that alternative medications such as herbal medicines and prayers are of great importance among Hispanic population. Alternative medicines are another reason for delay care and visits to the doctor among this population. Acknowledgement of this issue is important as these cultural practices can predispose patients to adverse events due to interactions.

Considering the multifaceted issue of low medication adherence, approaches aimed at anticipating adverse drug events also vary. For example, Waddington et al., [4] emphasize the threats of using complementary and alternative means of treatment in combination with conventional therapies under conditions of poor therapeutic monitoring. Waddington et al., [4] suggest educating healthcare providers about possible harms that patients may self-inflict even when using seemingly harmless means of complementary and alternative medicine without reporting such interactions. Therefore, nurse practitioners should be encouraged to consult patients on the matter of potential interactions between prescribed conventional medications and various types of complementary and alternative medicine. As for the ways of delivering educational interventions to healthcare providers and nurse students, Hawley et al., [2] recommend using a computer-based simulation that assists them in mastering the skills of helping patients on polypharmacy manage correctly and effectively their drug prescription lists. In this regard, a proper approach is combining the lists taken from patients’ electronic health records with printed copies. For the offices that are using EMR during transition of care, this option can be of great benefit.

Wolff et al., [7] propose using printed drug prescription lists in combination with open-ended questions that are supposed to be used to check patients’ understanding of the effects and interactions, dangers and benefits of their drugs that they are prescribed to take. Garfield et al., [3] emphasize that “patients often carry medication lists to mitigate information loss across healthcare settings” (p. 1). In a case of not having printed drug prescription, during follow-up rechecking of patients’ treatment adherence by means of asking them to write down all medications that used to consume, the discrepancies were frequently detected [6]. Therefore, keeping a printed drug prescription list is effective in preventing information loss when a patient goes from one medical specialist to another [1]. Besides, having printed drug prescription lists will become habitual for patients and their family members and this can be helpful in preventing adverse drug events after hospital discharge.

Furthermore, to ensure therapeutic monitoring over patients’ treatment adherence, Reedy et al., [10] recommend considering weekly structured telephone interviews with patients. In particular, such calls are aimed at checking that patients follow their treatment protocols. Apart from that, it is a good way to remind patients and their family members about possible interactions between conventional treatment and alternative medicine, possible drug-to-food interactions, and dangers that stem from combining substances (illicit drugs, alcohol and nicotine) with prescribed drugs.

Another alternative to the phone calls may be consulting patients using online platforms available from their electronic health records [11]. This approach is characterized by some mistakes, for example, it implies that patients have constant access to the internet, and are active users, who are willing to receive consultations done by nurse practitioners and/or pharmacists regarding their electronic drug prescription lists. Assuming that it is not possible in respect to each patient, the two above-discussed means of therapeutic monitoring can be proposed to patients and their family members as preferable options. In this case, the care is patient-centered because clients are allowed to pick the most convenient way of being consulted about drug safety behaviors.

PURPOSE/ PICO CLINICAL QUESTIONS/OBJECTIVES

The purpose statement

The purpose of the present DNP project is to advance patient safety by improving medication reconciliation in ethnic minority patients (Hispanic population) who receive polypharmacy and are observed to have frequent issues with adhering to their drug prescription lists.

Background clinical questions

The background clinical questions that stem from the project goals are:

What category of patients represents a vulnerable population that should be assisted?

What are the current issues related to adverse drug events at this Primary Care Office in South Florida?

What communication techniques are effective in educating patients about the importance of adhering precisely to treatment recommendations under conditions of polypharmacy? What communication strategy/intervention is feasible? Time and cost efficient?

What outcomes can be taken as the indicator of successfully achieved goals of this DNP project?

PICOT

- • P- Adult Hispanic population with polypharmacy in primary care

- • I- Providing patients with education on their medications (purpose/indication/side effects) followed by family inclusion and weekly follow up

- • C- Treatment as usual (without any process of medication reconciliation and limited education)

- • O- Increase patients’ pharmacovigilance and avoid adverse drug events.

- • T- in a 15-week-period

Study objectives

Medication reconciliation should be indicated as a central objective of this study since this process takes place simultaneously with the process of patients’ education and engagement to adhere to treatment protocols. A picked evidence-based intervention will be printed medication lists followed by open-ended questions on their medications (purpose/indication/side effects) followed by family inclusion [12]. This intervention is an independent variable that is deployed to manipulate the dependent variables, which are pharmacovigilance of patients and adverse drug events. Family inclusion in the process of medication reconciliation is an innovative component of this project. This initiative is deployed to increase collaboration and involvement between healthcare providers, patients, and their family members. The rationale of such choice is that participation of patients and their families in the process of medication reconciliation is expected to be the most effective way to prevent adverse drug events [13]. Therefore, providing patients with printed drug prescription lists, education on their medications, and monitoring their adherence through weekly phone calls and a trusted family member, is expected to be a proper innovative step in medication reconciliation.

DEFINITION OF TERMS

Adverse drug events constitute a group of issues related to insufficient patient safety stipulated by drugs prescription errors, poor healthcare literacy of patients, and/or low treatment adherence. Armor et al., [5] distinguish adverse drugs events that have already occurred and caused certain amount of harm to patients, and potential adverse drug events that can be anticipated. Striving to advance medication reconciliation healthcare providers work on detecting and decreasing adverse drug events and preventing potential adverse drug events.

Medication adherence is a phenomenon that demonstrates “the extent that a person’s behavior, such as taking medications, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider” [14]. In other words, medication adherence pertains to patients’ determination to follow treatment protocol that was agreed with their healthcare providers.

Medication reconciliation is defined as the process of creating the most accurate list possible of all medications a patient is taking including drug name, dosage, frequency and route and comparing that list against the physician’s admission, transfer, and/or discharge orders, with the goal of providing correct medications to the patient at all transition points within the hospital [15]. Medication reconciliation incorporates comparing patients’ current drug prescription lists with the new lists of medications that need to be prescribed; making on the basis of this comparison a new list that anticipates double prescriptions and malevolent interactions, and communicating the new list to patients and their family member [16]. Besides, it should be emphasized that patients may start taking some over-the-counter medicines during treatment, as well as, may experience adverse drug events caused by harmful drug-to-food interactions and/or substance use combined with prescribed medicines. Therefore, the task of healthcare providers is to anticipate all possible dangerous adverse drug events and educate patients about potential negative outcomes in a form that is understandable for them and (if possible) does not conflict with their cultural domains.

Pharmacovigilance is a term that is used referring to the goal of ensuring drug safety by means of reducing the frequency of occurred and potential adverse drug events. In this regard, pharmacovigilance provides wide opportunities for conceptualization of medication reconciliation [13]. For example, it can be viewed as the responsibility of healthcare providers, and/or pharmacists. Hence, pharmacovigilance can also be viewed from the perspective of patients’ motivation and intrinsic engagement to adhere to treatment protocol. In addition, pharmacovigilance is also relevant for family members of patients since they can help patients avoid adverse drug events.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND CONCEPTUAL UNDERPINNING

The theoretical background is regulatory pharmacovigilance and the conceptual underpinning is patient engagement [13]. The rationale for picking this concept is that “engaging patients and Healthcare Professionals (HCPs) as the stakeholders closest to the prescribing and use of medicines, can support pharmacovigilance systems across various settings, e.g. regulatory bodies, pharmaceutical companies and healthcare” [13].

Discussing the concept ‘patient engagement’ it is appropriate to emphasize that there are different approaches to motivate patients adhere to their prescription lists. Specifically, the depth of educational intervention is predefined by its form, which can be information, consultation, or participation. The first option presumes “a one-way form of information giving”, and it is the least deep form of engagement [13]. The second option, consultation, is a two-way form of engagement, in which patient also participates actively; hence, this communication is asymmetric in terms of involvement because a healthcare provider who gives consultation is the main participant of this process. In contrast, the third option that is participation is “a two-way and more open flexible approach where engaged persons and groups have more initiative and input in the timing and nature of the discussions” [13]. This method of engagement is preferable because due to the deepest level of involvement, can potentially be the most effective in ensuring patients’ pharmacovigilance and encouraging their family member to participate in the process of prevention of the adverse drug events.

METHODOLOGY

Setting and participants

The setting of this project is A Primary Care Office in South Florida. The participants are adult Hispanic patients who receive polypharmacy and their family member. The assistance is provided by a nurse practitioner (The author of this project). The permission to conduct the present educational project is obtained from the Medical Director of the Primary Care Office.

Description of approach and project procedures

Patients will be given a medication reconciliation form where they can list all prescribed medicines and place important information about each drug prescription (when prescribed, by whom, doses, duration of treatment, etc.). Besides, the printed drug prescription list is accompanied the following questions that consist of simple language, which can be understood without barriers by all patients. The list of questions below is aimed at verifying patients’ treatment adherence, and identifying possible discrepancies. Open Ended Questions for the Project:

What gets in the way of you taking your medication as prescribed?

Do you know why you were prescribed the medication you are taking?

Can you tell me what each of the medications is for and how you are supposed to take them? In a case of discrepancies detected, a patient will be educated about drug safety in a patient-centered mode that is aimed to fill in an identified gap in knowledge, as well as encourage adhering to treatment protocol. Apart from that, each patient will be asked to provide the contact of one family member/close person who can be involved into participation in the process of pharmacovigilance. Specifically, this trusted person will be called weekly (if necessary) during 15 weeks to check patients’ adherence to provided prescriptions. In a 15-week-long period, another meeting with the sample will be arranged during which they will be asked the same questions. The indicator of success will be improved treatment adherence (fewer amount of discrepancies, stronger engagement in treatment adherence).

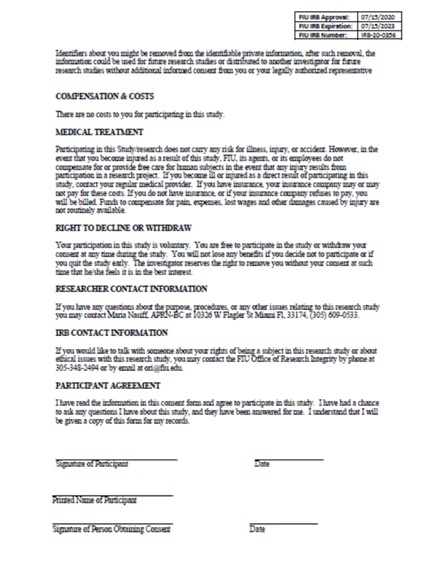

Protection of human subjects

The sampling method is purposive sampling. The targeted sample size will be 20 participants among patients, as well as 1 participant, a family member, for each of the recruited patients. The sample will be recruited through a conference call. These same methods (a phone call) will be used to explain the project as a whole and to gather answers for the survey. Then an email will be sent to provide documentation (brochures, and informed consent) to all patients who fit in the sample inclusion criteria. In particular, the inclusion criteria are being an adult, belonging to Hispanic ethnicity, who receive polypharmacy, having a family member/trusted person with whom the patient will be willing and comfortable sharing drug prescription list and who will be willing to participate. The brochure will contain the title of project, purpose and short description, as well as, it will briefly highlight the benefits of taking part in the present educational project. Since this Project is educational, it does not present any potential risks for participants. The sample will be asked to sign informed consent (in their preferred language) and to return this documentation back through email. All obtained data will be coded and held in hard copy versions.

Data collection

The data will be collected directly from patients during conference call meeting. The data will be retrieved two times: during pre-intervention and post-intervention measurement. The data will be collected by a nurse practitioner (the author of the project) in simple mode by giving one score to each correct answer on the questions (survey). Similarly, to ensure reliability, test-retest will be conducted as appropriate. The test-retest will be done with one-week interval. This approach will help avoiding biases. The validity of findings is ensured by constructing the questions that are clear and understandable for patients and their significant others. To ensure face validity, all procedures of data collection will be written. All participants will be informed about the procedure. In addition to data related to patients’ treatment adherence, inferential statistics will be collected and presented in a written form, as well as in a form of supportive visuals (tables). Patients’ demographics such as phone number, age, gender, chronic conditions, and medicines taken will be indicated.

Data management and analysis plan

The data (all printed and written materials) will be kept securely in hard-copies by the author of the research, and by supervisor. To ensure the confidentiality, the results will be coded using patient’s birthday and gender. Received statistical data will be calculated manually and rechecked.

The plan for quality improvement next steps

The results of this quality improvement project will be presented to fellow colleagues at the clinic. Information will be shared regarding the patients’ low healthcare literacy issues, poor communication skills, and limited education on their medications as being the main factors that lead to their reluctance to adhere to treatment plans. The results of this pilot study outline the possible steps to be followed to complete medication reconciliation in this population. These steps may be an effective way in avoiding injury and ADE among our adult patients. The importance of regular telephone-based communication for the purpose of monitoring patients’ pharmacovigilance will be emphasized as a way to communicate with the patients and their family members regarding any issues or concerns about their plan of care.

The plan for sustaining the practice change

The plan for sustaining the practice change is to create a position that will follow the guidelines established in this pilot study. The steps for weekly contact have demonstrated an increase in trust with the patients as well as improved knowledge in regards to medication education. If this practice chooses to implement these new guidelines a decision about who will be responsible for this communication and education will be necessary. Finally, financial consideration concerning the increased time needed to communicate with these patients is expected. Evaluation of the additional cost of more man hours to improve patient outcomes may be necessary to include as part of the practice guidelines.

Discussion of the results at the end of the qi project

The initial sample size was 20 patients and their family members. Of the 20 initial participants, two patients quit the quality improvement project due to change in their healthcare provider. The remainder of the 18 recruited patients participated in the project for the full 15 weeks. The 15-week span that reviewed medication reconciliation, education, and treatment adherence through a telephone call was evaluated. The results of the survey proved a benefit to the approach of medication reconciliation. Specifically, the recruiters were asked to leave feedback about their experience obtained while participating in this quality improvement project. Patients and their family members reported a positive experience with the telephone encounters. The opportunity to develop a more open, trustworthy relationship through frequent interactions with the provider showed a positive change in attitude and behavior. As a result, the participants became more competent and self-confident in adhering to their treatment plans. In addition, they increased their health literacy and became more comfortable with taking prescribed medication and more informed of the treatment process.

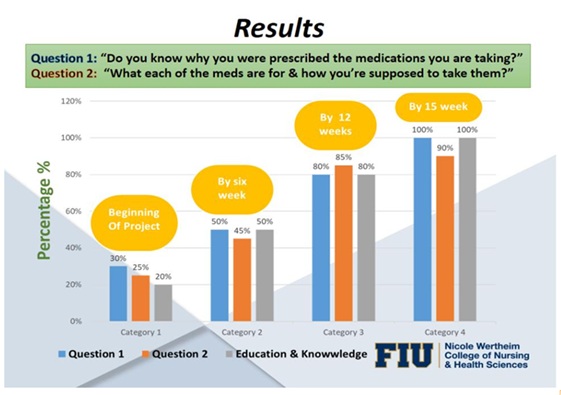

The qualitative feedback matched statistical results. In particular, almost all patients answered the study questions with a positive regard. For example, answering the question ‘Do you know why you were prescribed the medications you are taking?’ 100% of patients answered positively. Moreover, answering the question ‘What gets in the way of you taking your medication as prescribed?’ 70% pointed out the lack of understanding/knowledge about the importance of treatment adherence. At the same time, patients and their family members indicated more than 80% improvement in adherence to treatment regime and greater self-efficacy after participation in this quality improvement project. Finally, when patients were asked ‘Can you tell me what each of the medications is for and how you are supposed to take them?’ 90% were capable of providing precise information about the purpose of medications, treatment effects, possible side-effects, and regime of taking their medicines.

In a word, the discussed quality improvement project was advantageous for patients who constituted this ethnic minority group and were on polypharmacy.

Despite the success of this project, there are significant concerns and limitations. The described approach of medication reconciliation is effective in a short-run prospective, but it is not clear how sustainable the change would be in a medium and long-run perspective. For example, one may assume that the patients’ health literacy, and motivation (and thus, their pharmacovigilance) would be decreased to natural processes of forgetting. Besides, the process of monitoring patients’ treatment adherence is time consuming, and it requires much additional input made by healthcare providers. Consequently, it would be expensive to maintain telephone-based monitoring of patients’ pharmacovigilance on a regular basis. In addition, it would require more nurses to be involved, which may be not always possible due to the expenses.

The implications for advanced nursing practice

This QI Project has reinforced the importance of educating patients and family members on their medications and adherence to treatment regimen. A weekly phone call to improve their knowledge and evaluate their compliance has been a great benefit for the patients who participated in this study. The results of the present project will be useful for health care providers; it demonstrates the usefulness of continued patient and family participation in conducting medication reconciliation. Despite the small sample size and low study rigors, this project may be considered as a pilot study for larger experimental researches focused on family involvement in the process of advancing pharmacovigilance. The present quality improvement project has important implications in terms of practice, education, organizations, and policy. The stakeholders in this project will benefit from frequent communication between the healthcare providers, and their family members. Furthermore, in terms of education, this project has shown that advanced practice nursing, education, and health promotion interventions are necessary in the prevention of medical errors and adverse drug events.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the identified area for quality improvement at the primary care office is the gap between current amount of ADEs and desired reduced drug-related errors and discrepancies in prescriptions and patients’ actual adherence. This gap is proposed to be decreased by improving medication reconsolidation and patient/family education. In particular, a communication improvement strategy is proposed to create a better relationship between Practitioner-patient and to facilitate education. In this regard, health care practitioners are expected to perform monitoring of patients’ adherence to treatment plans, as well as perform educational and motivational functions. Apart from expected strengths, this project is assumed to increase positive reputation of this primary care office, which is expected to strengthen its sustainability and open the door for new clients and collaboration opportunities.

REFERENCES

- Marcum ZA, Kisak A, Visoiu A, Resnick N (2016) Medication discrepancies and shared decision aking. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 64: 653-654.

- Hawley CE, Triantafylidis LK, Phillips SC, Schwartz AW (2019) Brown bag simulation to improve medication management in older adults. The Journal of Teachingand Learning Resources 15: 1-9.

- Garfield S, Furniss D, Husson F, Etkind M, Williams M, et al. (2020) How can patient-held lists of medication enhance patient safety? A mixed-methods study with a focus on user experience. Bio Med Journal Quality & Safety 1-10.

- Waddington F, Lee J, Naunton M, Kyle G, Thomas J, et al. (2019) Complementary medicine use among Australian patients in an acute hospital setting: An exploratory, cross sectional study. Bio Med Central Complementary and Alternative Medicine 19: 1-7.

- Armor BL, Wight AJ, Carter SM (2016) Evaluation of adverse drug events and medication discrepancies in transitions of care between hospital discharge and primary care follow-up. Journal of Pharmacy Practice 29: 132-137.

- Coletti DJ, Stephanou H, Mazzola N, Conigliaro J, Gottridge J, et al. (2015) Patterns and predictors of medication discrepancies in primary care. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 21: 831-839.

- Wolff CM, Nowacki AS, Yeh J-Y, Hickner JM (2014) A randomized controlled trial of two interventions to improve medication reconciliation. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 27: 347-355.

- Green RR, Santoro N, Allshouse AA, Neal-Perry G, Derby C (2017) Prevalence of Complementary and Alternative Medicine and Herbal Remedy Use in Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White Women: Results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine 23: 805-811.

- Sobel LL, Metzler Sawin E (2016) Guiding the Process of Culturally Competent Care With Hispanic Patients. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 27: 226-232.

- Reedy AB, Yeh JY, Nowacki AS, Hickner J (2016) Patient, physician, medical assistant, and office visit factors associated with medication list agreement. Journal of Patient Safety 12: 18-24.

- Ottney A, Koski R (2018) Addressing meaningful use and maintaining an accurate medication list in primary care. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 58: 186-190.

- Greenwald JL, Halasyamani LK, Greene J, LaCivita C, Stucky E, et al. (2010) Making inpatient medication reconciliation patient centered, clinically relevant, and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. Joint Commission Journal on Quality & PatientSafety 36: 504-513.

- Brown P, Bahri P (2019) ‘Engagement’ of patients and healthcare professionals in regulatory pharmacovigilance: Establishing a conceptual and methodological framework. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 75: 1181-1192.

- Dudzinski K (2015) Speaking to patients about medication adherence. Michigan Pharmacists Association (MPA).

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement (2020) Medication reconciliation to prevent adverse rug events. Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Tokyo, Japan

- Aronson J (2017) Medication reconciliation. Bio Med Journal 356: 5336.

|

A List of Tasks |

Timeline |

|

To contact Medical Director, explore areas for improvement and get approval for the |

01/16/20-01/31/20 |

|

present project. Meet with staff, think about possible candidates that will benefit |

|

|

entering this project. |

|

|

|

|

|

To Start the creation of a medication list, survey questions, catchy design of the |

|

|

brochures, and informed consent with translation (Spanish). Also, discussed |

02/06/20-03/15/20 |

|

implementation and agree on the weekly phone calls to patients/main caregiver to |

|

|

follow up on their regimens and to provide education. |

|

|

|

|

|

To begin recruitment process. Collect data on patients’ demographics. Collect data |

04/06-04/30- 2020 |

|

about patients’ pharmacovigilance. Make the first call to patients & family member |

|

|

to set meeting. |

|

|

To begin the IRB process |

05/11/ 2020 |

|

To meet with individuals/family members who are willing to participate, to discuss |

05/18-06/18- 2020 |

|

the details of the project, obtain informed written consent, and initial survey. |

|

|

|

|

|

Arranging & coding the files from participants. Safe files in a secure place. Created a |

06/21-07/05 - 2020 |

|

separate medication list for each patient to be used when providing education in an |

|

|

organized manner. |

|

|

-Fifteen weeks of weekly follow-up phone calls, education, and monitoring patient’s |

07/07-10/15 – 2020 |

|

regimen. |

|

|

-Final survey gather on last weekly phone call on 10/15/2020. |

|

|

|

|

|

Inferential statistics obtained. Conduct post-intervention measurements. compare |

10/16-10/30 - 2020 |

|

pre- and post-intervention data. |

|

|

To create a report on the work done. |

11/01-11/20 - 2020 |

|

|

|

|

To disseminate results. |

11/30/2020 |

Timeline: A List of Tasks and a Timeline for the Project.

APPENDICES

IRB Approval Letter

Survey Questionary

The following questions will be done to participants at the beginning/end of the study to score/evaluate outcome (Adherence and knowledge to regimens/medications)

- Is the Patient an adult Hispanic?

_________________________________________

- Is the Patient having polypharmacy (2 or more medications)?

______________________________________________________________________

Patient's answer to the following questions:

- Do you know why you were prescribed the medications you are taking?

________________________________________________________________________________

- What gets in the way of you taking your medication as prescribed?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

- Can you tell me what each of the medications are for and how you are supposed to take them?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The answers will be compared to the score done at the beginning of the study. If the answers to this questions show positive results the goals will be.

Brochure created for the project

Inform Consent Approved by IRB for this Project

POSTER PRESENTATION

CLICK LINK TO DOWNLOAD POSTER

Citation: Nasiff ME (2021) Medication Reconciliation and Patient Education at a Primary Care Office in South Florida. J Altern Complement Integr Med 7: 143.

Copyright: © 2021 Maria Elena Nasiff, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.