Membranous Glomerulopathy with Light Chain Restriction

*Corresponding Author(s):

Javier Carbayo Lopez De PabloDepartment Of Nephrology, University Hospital Gregorio Maranon, Madrid, Spain

Email:jcarbayo92@gmail.com

Abstract

Membranous nephropathy is considered the main cause of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in adults. Mostly caused from the deposition of polytypic immune complexes along the subepitelial slope of the glomerular basement membrane, cases with light chain isotype-restricted deposits have been described.

We describe a 75-year-old female diagnosed of chronic lymphocytic leukemia who achieved remission after treatment with steroids and rituximab. Five years later, the patient debuted with clinical nephrotic syndrome and mild worsening of kidney function. A biopsy was performed with evidence of membranous glomerulopathy with light chain monotypic deposits of IgGk. Immunofluorescence staining and electron microscopy findings were compatible with a secondary cause and monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance was suspected. A marrow bone biopsy was carried out, confirming infiltration by the limphoproliferative process. She then recieved treatment with rituximab, dexamethasone and proteasome inhibitors with recovery of kidney function and partial resolution of proteinuria.

This case highlights the need to consider light chain restriction membranous nephropathy in the differential diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome. It also emphasises the different posible renal involvement by limphoproliferative process.

Introduction

Membranous nephropathy is considered the main cause of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in adults. Mostly caused from the deposition of polytypic immune complexes along the subepitelial slope of the glomerular basement membrane, cases with light chain isotype-restricted deposits have been described.

Different types of circulating antibodies have been involved in the pathogenesis of primary MN; 75-80% of patients have anti-Phospholipase A2 Receptor (PLA2R) antibodies and 2-5% against Thrombospondin Type 1 Domain-Containing 7A (THSD7A) [1]. Other antibodies can also be produced secondary to infections, malignancy, autoimmune disease, Limphoproliferative Disorders (LPD) or drugs. They permeate the glomerular basement membrane and interact with podocytes epitopes to form immune-complexes along the glomerular basement membrane.

Rare cases and small series of MN with deposition of monotypic immune complexes with light chain restriction by immunofluorescence have been described. It represents only a 0.95% of MN cases [2]. Its pathogenesis, prognosis and clinical implications are not clear but some of them have been associated with an underlying LPD. In this condition a Monoclonal Gammopathy of Renal Significance (MGRS) should be rule out.

MGRS include a group of renal injuries or diseases caused by a nephrotoxic immunoglobulin, generated by a clonal proliferative disorder, which does not meet the previously defined hematological criteria for treatment of a specific malignancy [3]. Mechanisms of glomerular nephrotoxicity are diverse, including deposition of immunoglobulin, precipitation/crystallization or complement and cytokine activation [4].

Recently, the International Kidney and Monoclonal Gammopathy Research Group (IKMG) has published a new classification of monoclonal gammopathy in 2019 [3], based on kidney biopsy findings by immunofluorescence and electron microscopy studies to identify the monotypic immunoglobulin deposits. This classification includes an entity defined as “miscellaneous”, which represent usual polyclonal glomerulopathies that sometimes presents with monoclonal immunoglobulin deposits, such as monotypic MN. It presents identical lesions on light microscopy and electron microscopy that typical polyclonal membranous nephropathy but with light chain restriction by immunofluorescence.

We report an atypical case of MN with light chain isotype-restricted deposits secondary to chronic lymphocytic leukemia which confers relevant modifications in its management.

Case Description

We describe a 75-year-old woman who was referred to Nephrology department after presentation with peripheral edema and nephrotic syndrome proteinuria. Her medical record was positive for hypertension, bronchial asthma, drug allergy to sulfamides and iodinated contrast. She had also been diagnosed of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) (CD38+) five years ago, debuting with hypo-regenerative anemia, erythroid hypoplasia and 50% bone marrow infiltration by leukemic lymphocytic cells. A regimen based on rituximab (4 doses of 375mg/m2) and corticosteroids (1mg/kg) was received and she achieved remission after 3 months of treatment. She continued follow up in Hematology consultations for stable lymphadenopathy (Rai I stage, Binnet A) and weak IgGk monoclonal gammopathy since then.

After 5 years of remission she started with clinical nephrotic syndrome. Laboratory testing, showed in table 1, resulted in nephrotic range proteinuria (4.6g in 24-hour urine sample), acute kidney injury (creatinine of 1.56mg/dl; eGFR by CKD-EPI of 48ml/min/1.73m2), hypoalbuminemia (albumin 3.1g/dl), hyperproteinemia (9.3g/dl) and IgGk monoclonal component increase up to a maximum of 2.2g/dl (with serum free light chain k /l ratio up to 25.6). Electrophoresis with immunofixation in urine was positive for k light chains. C3 and C4 levels resulted within the reference ranges.

Kidney ultrasound showed normal-sized kidneys, with increased echogenicity bilaterally, without pyelocaliceal dilation. Immunological and serologic tests were performed, testing for cryoglobulin, ANCA, ANA, Hepatitis C (HCV), Hepatitis B (HBV) and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) all negative.

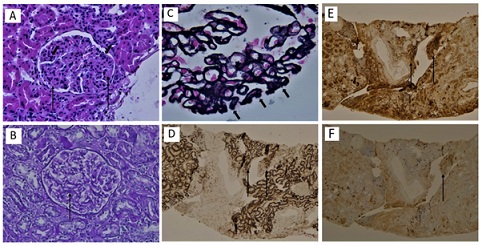

After these findings, a kidney biopsy was performed. Light microcopy showed 36 glomerulus, only 2 were globally sclerosed (5%), the rest of them appeared hypertrophic with stiffness of the glomerular capillary loops as well as diffuse mesangial expansion with focal increase of mesangial cellularity (Figures 1A and 1B). Jones silver positive stains (spikes) were focally observed in the subepithelial slope of glomerular basement membranes (Figure 1C). No crescents, endocapillary proliferation or double contours were evidenced. A mild inflammatory lymphoid infiltrate was noted, testing positive to monotypic plasmatic cells IgGk by Immunohistochemical (IHQ) techniques (Figures 1D-1F), without interstitial fibrosis or tubular atrophy. Small vessels and arterioles had no alterations.

Figure 1: Kidney biopsy findings: light microscopy. (A) The glomerulus shows diffuse mesangial expansion (large arrows) and focal mesangial hypercellularity (small arrow) (H&E stain, x20). (B) Another glomerulus shows global mesangial expansion by periodic acid-Schiff x20 (large arrow). (C) Stiffness of the glomerular capillary loops and spikes were focally observed in the subepithelial slope of glomerular basement membranes (Jones methenamine silver stain, x40). A mild inflammatory lympho-plasmacytic infiltrate was evidenced testing positive for CD138. (D) Kappa (E) and negative for lambda (F) by immune histochemical techniques, x20 (large arrows).

Figure 1: Kidney biopsy findings: light microscopy. (A) The glomerulus shows diffuse mesangial expansion (large arrows) and focal mesangial hypercellularity (small arrow) (H&E stain, x20). (B) Another glomerulus shows global mesangial expansion by periodic acid-Schiff x20 (large arrow). (C) Stiffness of the glomerular capillary loops and spikes were focally observed in the subepithelial slope of glomerular basement membranes (Jones methenamine silver stain, x40). A mild inflammatory lympho-plasmacytic infiltrate was evidenced testing positive for CD138. (D) Kappa (E) and negative for lambda (F) by immune histochemical techniques, x20 (large arrows).

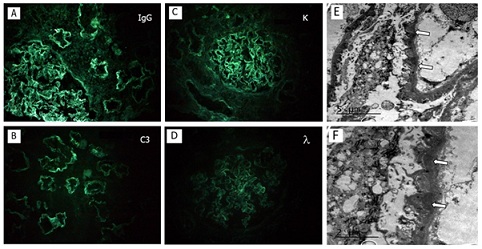

Immunofluorescence staining for IgG (3+) (Figure 2A) and C3 (2+) (Figure 2B) resulted positive, with diffuse and granular pattern over capillary wall in subepithelial slope of glomerular basement membranes but also in tubular membranes and Bowman capsule. C4d (2+) was positive in the same glomerular and tubular pattern. klight chain restriction was presented (2+) (Figures 2C and 2D). Staining for IgA, IgM, C1q and fibrinogen was negative. IHQ techniques for Phospholipase A2 Receptor (PLA2R), Congo red stain and IgG4 resulted negative.

Figure 2: Kidney biopsy findings. (A,B) Diffuse and granular pattern staining for IgG (3+) and C3 (2+) over subepithelial slope of glomerular basement membranes as well as tubular membranes and Bowman’s capsule.Staining for IgA, IgM, C1q and fibrinogen was negative (immunofluorescence image x 20). (C) Staining for κ light chains (2+). (D) λ light chain stain was negative. (E) The figure shows focal foot processes effacement and electron-dense deposits located in the subephitelial slope (arrows) (electron microscopy). (F) Magnification of electron-dense deposits (electron microscopy).

Figure 2: Kidney biopsy findings. (A,B) Diffuse and granular pattern staining for IgG (3+) and C3 (2+) over subepithelial slope of glomerular basement membranes as well as tubular membranes and Bowman’s capsule.Staining for IgA, IgM, C1q and fibrinogen was negative (immunofluorescence image x 20). (C) Staining for κ light chains (2+). (D) λ light chain stain was negative. (E) The figure shows focal foot processes effacement and electron-dense deposits located in the subephitelial slope (arrows) (electron microscopy). (F) Magnification of electron-dense deposits (electron microscopy).

On electron microscopy, focal foot processes effacement was evidenced (30-40% of capillary loops) with irregular basement membranes and electron-dense deposits located in the subephitelial slope and in the thickness of the basement membrane (Figures 2E and 2F). Mesangial deposits and in tubular membranes were also observed.

A diagnosis of secondary membranous nephropathy (stage 3-4) with IgGk light chain monotypic deposits was reached. Monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance diagnosis was suspected and a marrow bone biopsy was carried out, confirming a nodular and interstitial infiltration by CLL (30%), without malignancy transformation, and a monotypic IgGk plasmacytosis (5%).

The patient received a treatment regimen of bortezommib, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone and rituximab (2 doses of 500mg/m2). A satisfactory evolution was presented, with recovery of renal function (plasmatic creatinine, 0.8mg/dl) and partial resolution of proteinuria after 2 months of treatment (0.2g in 24-hour urine sample). There was a significative decrease in serum IgGk monoclonal component (0.6g/dl) with persistence of positive weak urine immunofixation.

Discussion

Exceptional cases of MN with light chain restriction have been described in case reports and limited series of cases.

Rocha AB and Larsen CP [2], collected the largest series of light chain restriction MN (28 cases). The majority of cases lacked a recognizable etiology, but 21% of patients presented a coexisting or a subsequently diagnosed LPD, being CLL the most repeated diagnosis. Most patients had no detectable monoclonal Ig in serum/urine by electrophoresis or immunofixation, consistent with other series, but there are also published cases with positive serum and urine protein electrophoresis [5]. klight chain restriction was the most frequent, representing the 85.7% (only l restriction in 14.3% of cases). In monoclonal MN, a rigorous search of the monoclonal Ig must be undertaken with protein electrophoresis and immunofixation analyses of serum and urine samples, as well as serum free light- chain assay. Our patient presented an identified serum and urine IgGk monoclonal component (2.2g/dl) and serum free light chain k /l ratio increased (25.6), which increased the suspicion of a secondary etiology.

In the series previously mentioned [2], PLA2R stained positive in 26% of patients with light chain restriction, but none of them presented an underlying LPD. Similarly, 28% of patients with positive staining for a single IgG subclass had an underlying LPD, compared to none of the cases with positive staining for more than 1 subclass. Dominant and co-dominant IgG4 staining is a principal finding in primary MN. In our case report PLA2R and IgG4 stain resulted negative, as key markers to suspect secondary etiology, although immunofluorescence staining for IgG subclasses was not performed.

These are additional clues to suspect a secondary etiology of the monotypic MN, but it should not be forgotten the value of the study of the tubule-interstitial compartment. In our patient, staining of IgG, C3 and k light chain resulted positive in tubular membranes and Bowman capsule.

Moreover, when a monoclonal component is detected and MGRS suspected, electron microscopy is often necessary to identify the specific MGRS - associated lesion. The final diagnosis was given by electron microscopy, showing no organized electron-dense deposits located in the subepithelial slope of the glomerular basement membrane (also mesangial deposits and in tubular membranes). Electron microscopy allows differential diagnosis with other causes of MGRS - related disease that can exhibit membranous pattern in light microscopy, such as Proliferative Glomerulonephritis and Monoclonal Immunoglobulin Deposits (PGNMID) or immunotactoid glomerulonephritis [3].

By other hand, CLL and LPD may affect kidney by different mechanisms: renal infiltration by neoplasic cells, tubular damage, obstruction from extrinsic compression, promoting infections or nephrotoxicity by medications and causing glomerular diseases [6,7]. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN, 36%) and membranous nephropathy (MN, 19%) are the most frequently reported etiologies associated. Prevalence of MN in renal biopsies of patients with CLL varies from 4 to 12%, but not all cases presented light chain restriction in immunofluorescence testing [8]. In our patient, mild inflammatory lymphoid infiltrate by plasmatic cells IgGk was also evidenced, probably contributing to renal injury.

Evidence about treatment of MN with light chain restriction is lacking, but once a MGRS is detected, clonal identification is mandatory and a specific treatment against it is required. There are cases of MN secondary to CLL with successful treatment with fludarabine [9]. Our patient received a treatment regimen of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone and rituximab, with recovery of renal function and significant reduction of proteinuria.

Conclusion

To summarize, light chain restriction membranous nephropathy is a rare entity occasionally caused by a detectable monoclonal gammopathy. We encourage performing electron microscopy study in these cases, sometimes necessary to reach an accurate diagnosis of the MGRS. Subsequently, when a limphoproliferative disorder is detected, treatment must be addressed to remove the underlying clone.

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding Sources

None.

Statement of Ethics

No ethics approval was required as this is a case study. Written and verbal consent was obtained from the patient.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- Couser WG (2017) Primary Membranous Nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 983-997.

- Rocha AB, Larsen CP (2017) Membranous glomerulopathy with light chain- restricted deposits: A clinicopathological analysis of 28 cases. Kidney Int Rep 2: 1141-1148.

- Leung N, Bridoux F, Batuman V, Chaidos A, Cockwell P, et al. (2019) The evaluation of monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance: A consensus report of the International Kidney and Monoclonal Gammopathy Research Group. Nat Rev Nephrol 15: 121.

- Leung N, Drosou ME, Nasr SH (2018) Dysproteinemias and glomerular disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 128-139.

- Guiard E, Karras A, Plaisier E, Van Huyen JPD, Fakhouri F, et al. (2011) Patterns of noncryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis with monoclonal Ig deposits: Correlation with IgG subclass and response to rituximab. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1609-1616.

- Doshi M, Lahoti A, Danesh FR, Batuman V, Sanders PW, et al. (2016) Paraprotein-related kidney disease: Kidney injury from raraproteins-what determines the site of injury? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 2288-2294.

- Wanchoo R, Ramirez CB, Barrientos J, Jhaveri KD (2018) Renal involvement in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Kidney J 11: 670-680.

- Strati P, Nasr SH, Leung N, Hanson CA, Chaffee KG, et al. (2015) Renal complications in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis: The Mayo Clinic experience. Haematologica 100: 1180-1188.

- Rocca AR, Giannakakis C, Serriello I, Guido G, Mosillo G, et al. (2013) Fludarabine in chronic lymphocytic leukemia with membranous nephropathy. Ren Fail 35: 282-28.

Citation: de Pablo JCL (2021) Membranous Glomerulopathy with Light Chain Restriction. J Nephrol Renal Ther 7: 067.

Copyright: © 2021 Javier Carbayo Lopez de Pablo, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.