Metastatic Malignant Melanoma of the Stomach: An Unexpected Phenomenon of the Disease

*Corresponding Author(s):

Mahvash NematollahiDepartment Of Pathology, Cancer Research Center, Babol University Of Medical Sciences, Mazandaran, Iran

Tel:+98-911-7701684,

Email:Rouhitina0@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Gastrointestinal (GI) melanomas are uncommon, and the stomach is a rare site for metastasis and accounts for 27% of the cases with GI tract metastatic melanoma. Clinical manifestations are usually nonspecific, and many patients are asymptomatic until the disease progresses further, but may be presented with nausea, vomiting, weight loss, abdominal pain, hematemesis, melena, and iron deficiency. The prognosis is very poor, and the median survival of the patient is 4 to 6 months. The diagnosis is confirmed with postoperative pathological examination and immunohistochemical study. Treatment options include surgical resection, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy.

Case Presentation: The presented case is a 71-year-old male, previously diagnosed with cutaneous melanoma of the left retroauricular region that presented with upper GI tract symptoms and cervical lymphadenopathies about one year after the diagnosis of the primary tumor. An upper GI endoscopy was done, and a pathological examination of the biopsy specimen confirmed the metastatic melanoma of the stomach.

Conclusion: Regarding the unfavorable outcome of gastric metastatic melanoma, the treatment choice is still under investigation. However, early diagnosis is important for the appropriate assessment of patients as candidates for surgical interventions.

Keywords

Malignant Melanoma; Stomach; Metastasis

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) melanomas are rare and, if detected, require thorough evaluation. Most GI melanomas are metastatic from a cutaneous primary [1]. Metastases to the GI tract can present at the time of early diagnosis or many years after the first sign of recurrence. Clinical manifestations are usually nonspecific, and many patients are asymptomatic until the disease progresses further, but may be presented with nausea, vomiting, weight loss, abdominal pain, hematemesis, melena, and iron deficiency [2-4]. Stomach is a rare site for metastasis and accounts for an average of 27% of the cases with GI tract metastatic melanoma. The postoperative mortality is almost 5%, and the median survival of patients is 4 to 6 months, with 1- and 5-year survival rates of 44% and 9%, respectively [5]. The endoscopic biopsy is a helpful method (but not accurate) for diagnosis [6, 7]. Due to the histological characteristics of metastatic gastric melanoma, it can be misdiagnosed microscopically as adenocarcinoma [8, 9]. The diagnosis is confirmed with postoperative pathological examination and identification of positivity for human melanoma black (HMB)-45, S-100, and vimentin and negativity for cytokeratin and p53 on immunohistochemical study (10). Treatment options include surgical resection, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy. Surgical resection may be considered a palliative intervention in symptomatic patients, and it can prolong survival [11]. Regarding the unfavorable outcome of gastric metastatic melanoma, the treatment choice is still under investigation. Here, we present this rare case and discuss it.

Case Presentation

The patient is a 71-year-old male diagnosed with cutaneous melanoma of the left retroauricular region one year ago. His family history was unremarkable. At the time of early diagnosis, he presented with a pigmented skin lesion in the posterior auricular skin. No lymphadenopathy was detected on physical examination, but neck sonography showed three lymph nodes with thick cortex and fatless hilum in level 5A of the left side of the neck (short axis: 6, 7, 7 mm). Thyroid gland assessment was normal (TIRADS1). Laboratory tests (on blood and urine samples) were also unremarkable. An excisional biopsy was taken from the lesion, and pathological examination showed a lentiginous melanoma with a vertical growth phase (5.6 mm thick with ulceration in Breslow thickness system: T4b and Clark level 5). Vascular and lymphatic invasion were not identified, and deep and two lateral surgical margins were evaluated; one lateral margin showed junctional nest of atypical melanocytes, and the other margins were free of tumor. The distance of this area from the surgical margins was 0.3 mm (very close). For this reason, complete excision of the lesion with a safe margin was recommended. According to IHC results, the specimen was diffusely positive for HMB-45 and Melan, and S100 and Ki-67 were positive in about 20% of the tumor cells. The patient underwent surgery, and postoperative pathological examination showed a lentigo maligna melanoma of left ear skin with 1.2 cm tumor size in greatest dimension without lymphovascular and perineural invasions. All surgical margins were free, and tumor distance from the closest margin was 6 mm. Four lymph nodes dissected from the posterior triangle of the neck were reactive and also free of the tumor. Four months after the resection of the tumor, multiple lymphadenopathies were detected in the left side of the neck, which neck sonography showed two lymph nodes in level 2B (short axis: 15, 19 mm), three lymph nodes in level 5A (short axis: 6, 8, 11 mm), and two lymph nodes in level 5B (short axis: 6, 7 mm). Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scans were asked for the staging of the disease. PET/CT findings revealed multiple FDG avid lymph nodes in the periauricular region, and levels IIA, IIB, and VB of the left side of the neck, that core needle biopsy was recommended. Also, there were two hypo-attenuating FDG avid lesions in bilateral liver lobes and one lesion at the tip of the spleen.

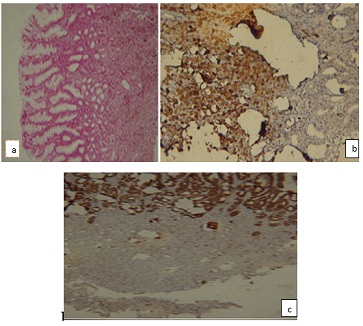

The patient complained of anorexia and regurgitation about one year after the diagnosis of the primary tumor. An upper GI endoscopy was done for him. The findings showed a 15×15 mm polypoid lesion in the stomach that was highly suspicious for metastatic melanoma (Figure 1), and a biopsy was taken from the lesion for pathological examination. IHC study reported positivity for HMB-45 in infiltrating discohesive cells and negative cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) in these cells. Therefore, the results were compatible with metastatic melanoma (Figure 2). This patient was advised chemotherapy and immunotherapy, but he refused.

Figure 1: Picture taken from upper GI endoscopy showing a 15 mm gastric polypoid lesion, highly suspicious for metastatic melanoma.

Figure 1: Picture taken from upper GI endoscopy showing a 15 mm gastric polypoid lesion, highly suspicious for metastatic melanoma.

Figure 2: Pigmented neoplastic cell infiltration in gastric mucosa: a) H & E. Immunohistochemistry staining b) positive for HMB-45 and c) negative for cytokeratin.

Figure 2: Pigmented neoplastic cell infiltration in gastric mucosa: a) H & E. Immunohistochemistry staining b) positive for HMB-45 and c) negative for cytokeratin.

Discussion

Although malignant melanoma of the digestive tract is an unusual malignancy with a very poor outcome. The primary site of melanoma is usually the skin, and metastases to the GI tract usually occur in the liver, small bowel, colon, and stomach, respectively, based on decreasing order of incidence [12]. Among the noncutaneous melanomas, almost 20% originate from mucosal sites, and of these, 25% are found in the GI tract [13].

In the cases with suspected metastatic melanoma to the upper GI tract, an endoscopy should be performed, and a biopsy should be taken from the lesion (if found). CT scan should be obtained to detection of metastases, but the modality is not highly sensitive for access to the goal [8, 14].

The endoscopic appearance of metastatic lesions in the stomach may be similar to the primary gastric tumors (early gastric cancer or advanced gastric cancer). Those resembling advanced gastric cancers include type 1 (polypoid tumor), type 2 (ulcerated tumor with sharply demarcated margins), type 3 (ulcerated tumor without definite borders), or type 4 (diffusely infiltrating tumor) [11]. Our patient's endoscopy findings were consistent with the appearance of advanced gastric cancer type 1. However, because of the variable morphology of tumors, no characteristic features were found on endoscopy that can detect the etiology of gastric metastases the diagnosis of metastatic melanoma is confirmed with the biopsy specimen when the immunohistochemistry stain is positive for S-100 and antibody HMB-45 [10].

Previous case reports have shown that gastric metastases usually occur over one year after diagnosis of the primary tumor. A study by Kim et al. showed that half of their cases of gastric metastases were detected during one year from the time of the diagnosis of the primary tumor (including melanoma) [15]. In our case, as above study, metastasis to the stomach was detected one year after the diagnosis of the primary tumor. Another study by Oda et al. showed that two-third of their cases of recurrent melanoma with gastric metastases occurred 3 years after diagnosis of primary tumor [16], but in a case reported by Farshad et al. the gastric metastatic melanoma was detected 15 years after the initial diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma of chest wall [11].

Treatment options for metastatic melanoma include surgical resection, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and, if needed, radiation therapy to symptomatic sites. Since immunotherapy and targeted therapy have been developed, systemic chemotherapy is not recommended as a first-line treatment [11]. In patients with acceptable functional status, surgical resection should be considered to increase survival time with more safety and lower complications than chemotherapy; however, more investigations are needed to assess its true benefits, especially regarding gastric tumor resection. Caputy et al. indicate that patients with total excision of intra-abdominal metastases had a 5% postoperative mortality, a median survival of 9.6 months, 1-year survival of 44%, and 5-year survival of 5% [17]. Gutman et al. showed a median survival of 11 months in cases that underwent surgical resection [18]. Furthermore, surgical resection can be very effective as a palliative intervention. Hao et al. reported that surgical resection for metastases to the abdomen was 100% palliative for their symptomatic cases [19], but pathologic evaluation in the study of Rausei et al. demonstrated a diffuse submucosal invasion by melanoma, confirming that R0 resection was achieved [20]. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the risks and benefits of surgery in selected patients.

Conclusion

This case report indicates that in patients with a history of cutaneous melanoma, the clinical manifestations of metastases to the GI tract may be nonspecific, and the cases might be asymptomatic. However, if found, the metastatic melanoma should be ruled out with an endoscopy. Although the disease in this stage has a very poor prognosis and the survival time is too short, early diagnosis is important to the appropriate assessment of patients as candidates for surgical interventions.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Clinical Research Development Unit of Rouhani Hospital.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Research Ethics and Patient Consent

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Babol University of Medical Sciences.

References

- Simons M, Ferreira J, Meunier R, Moss S (2016) Primary versus Metastatic Gastrointestinal Melanoma: A Rare Case and Review of Current Literature. Case Reports in Gastrointestinal Medicine. 2016: 2306180.

- Liang KV, Sanderson SO, Nowakowski GS, Arora AS (2006) Metastatic malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Mayo Clin Proc. 81: 511-6.

- Iadevaia MD, Sgambato D, Miranda A, Ferrante E, Federico A, et al. (2017) Amelanotic metastatic melanoma of the stomach presenting with iron deficiency anemia. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 80: 327-328.

- Ghorbani H, Rouhi T, Vosough Z, Shokri-Shirvani J (2022) Drug-induced hepatitis after Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccination: A case study of a 62-year-old patient. Int J Surg Case Rep. 93: 106926.

- Santos-Seoane SM, Pérez-Casado L, Helguera-Amezua C, Diez-Fernández M (2019) Metastatic melanoma of the stomach. Cir Esp (Engl Ed). 97: 51.

- Koga N, Kubo N, Saeki H, Sasaki S, Jogo T, et al. (2019) Primary amelanotic malignant melanoma of the esophagus: a case report. Surgical Case Reports. 5: 4.

- Fukuda S, Ito H, Ohba R, Sato Y, Ohyauchi M, et al. (2017) A Retrospective Study, an Initial Lesion of Primary Malignant Melanoma of the Esophagus Revealed by Endoscopy. Intern Med. 56: 2133-2137.

- Bahat G, Saka B, Colak Y, Tascioglu C, Gulluoglu M (2010) Metastatic gastric melanoma: a challenging diagnosis. Tumori. 96: 496-7.

- Karimi E, Rouhi T, Saeedi N, Golparvaran S, Yazdani N, et al. (2022) Occult nodal metastasis in head and neck carcinoma patients treated with chemoradiotherapy. Am J Otolaryngol. 43: 103361.

- Kuwabara S, Ebihara Y, Nakanishi Y, Asano T, Noji T, et al. (2017) Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus treated with subtotal esophagectomy: a case report. BMC Surgery. 17: 122.

- Farshad S, Keeney S, Halalau A, Ghaith G (2018) A Case of Gastric Metastatic Melanoma 15 Years after the Initial Diagnosis of Cutaneous Melanoma. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2018: 7684964.

- Mihajlovic M, Vlajkovic S, Jovanovic P, Stefanovic V (2012) Primary mucosal melanomas: a comprehensive review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 5: 739-53.

- Kottschade LA, Grotz TE, Dronca RS, Salomao DR, Pulido JS, et al. (2014) Rare presentations of primary melanoma and special populations: a systematic review. Am J Clin Oncol. 37: 635-41.

- Taherinezhad LA, Kamrani G, Rouhi T, Nikbakhsh N (2022) Primary retroperitoneal mucinous cystadenoma in a female patient: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 94: 107099.

- Kim GH, Ahn JY, Jung HY, Park YS, Kim MJ, et al. (2015) Clinical and Endoscopic Features of Metastatic Tumors in the Stomach. Gut Liver. 9: 615-22.

- Oda, Kondo H, Yamao T, Saito D, Ono H, et al. (2001) Metastatic tumors to the stomach: analysis of 54 patients diagnosed at endoscopy and 347 autopsy cases. Endoscopy. 33: 507-10.

- Caputy GG, Donohue JH, Goellner JR, Weaver AL (1991) Metastatic melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Results of surgical management. Arch Surg. 126: 1353-8.

- Gutman H, Hess KR, Kokotsakis JA, Ross MI, Guinee VF, et al. (2001) Surgery for abdominal metastases of cutaneous melanoma. World J Surg. 25: 750-8.

- Hao XS, Li Q, Chen H (1999) Small bowel metastases of malignant melanoma: palliative effect of surgical resection. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 29: 442-4.

- Rausei S, Pappalardo V, Boni L, Dionigi G (2018) Laparoscopic intragastric resection of melanoma cardial lesion. Surg Oncol. 27: 642.

Citation: Hosseini A, Rouhi T, Nematollahi M, Shirvani JS (2023) Metastatic Malignant Melanoma of the Stomach: An Unexpected Phenomenon of the Disease. J Clin Stud Med Case Rep 10: 0152.

Copyright: © 2023 Akram Hosseini, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.