(Non) Organization of Paliative Care for Children in Bosnia And Herzegovina

*Corresponding Author(s):

Verica MisanovicPediatric Clinic, Clinical Center University Of Sarajevo, Patriotske Lige 81, 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia And Herzegovina

Email:vericamisanovic@gmail.com

Abstract

Palliative care is an approach to the comprehensive care of a patient suffering from a chronic, incurable disease when the curative methods of treatment have been exhausted. It is directed at suppressing pain and other symptoms, as well as physical, psychological, spiritual and social problems, requiring a multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approach, directed at the patient, family and community. Each person has the right to face their advanced or terminal illness without pain and with as little suffering as possible. The central objective of palliative care is to preserve the best possible quality of life until its end. In the creation and development of palliative medicine, the education of members of multidisciplinary palliative teams, as well as the general public, is extremely important, as is the drafting of international and national strategic plans for the development of palliative care. In addition to providing the best possible care, the main task of the medical staff in intensive care units is to educate and prepare the family to care for the sick member following his/her discharge from the hospital. The objective of this paper is to present palliative care in intensive care units, and the necessity of providing organized palliative care in home conditions, opening of hospices and palliative institutions in the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina with the aim of reducing the burden on intensive care units, the costs incurred by the long-term hospitalization of stable palliative patients in the intensive care units, and, most importantly, to ensure the quality of life of palliative patients and their families.

Keywords

Children, Palliative care, Organization

Introduction

A person, a parent, and very often a professional doctor, involved in the medical treatment of a sick child, has a hard time accepting the fact that with all the technical achievements of modern medicine and all the applied therapy, the expected results of the child's treatment are missing. There is an increasing consensus among doctors and bioethicists, that on the border between life and death, the only proper procedure is to do whatever is necessary to facilitate dying. When we find ourselves in a situation where the treatment did not provide the desired result, when no improvement is evident, or the quality of life is unacceptable, and when the dignity of the human person is lost, then the only remaining solution is palliative care. When making such a difficult decision, each case concerning a sick child should be considered separately, and this complex process must include doctors, parents, and other health professionals. Since we live in a country where a large part of the population consider themselves to be believers, express their affiliation to various religious groups, active participation of religious officials is also required [1].

Nowadays, the contemporary understanding of the medical science division, in addition to preventive and curative medicine, puts special attention on palliative medicine as a third medical branch. Apparently, palliative medicine existed before other branches of medicine, taking place in patients’ homes, but the novelty of modern society is in the medical approach - pain therapy, and health care, which enabled a good insight into the basic needs of seriously ill and dying patients. Palliative medicine encourages the need for mutual communication between individuals involved in such care; emphasizes humanity, teamwork; deals with the observation and needs not only of the patient but also of his/her family; encourages discussions and asks questions that can partly be answered by bioethics [2]. According to the definition provided by the World Health Organization, palliative care is an approach to the comprehensive care of a patient suffering from a chronic, incurable disease when the curative methods of treatment have been exhausted. It is aimed at suppressing pain and other symptoms, physical, psychological, spiritual and social problems, it requires a multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approach, and is directed at the patient, family and community. The central objective of palliative care is to preserve the best possible quality of life until its end [3].

Each individual is a unique biological, psychological, social and spiritual being with the right to health, if he/she is sick then the right to health care and recovery, and if recovery is not possible then the right to a painless and dignified death. Pediatric palliative care represents full, active care of a sick child, and includes all aspects of personality: somatic, psychological and mental- spiritual. As a separate specialization in some parts of the world, it connects the key factors of palliative care and clinical pediatric practice, aiming to improve the quality of the last phase of a child's life. This type of care respects the differences specific for the pediatric age, such as development, moral and legal status, type of illness, right to schooling.

Palliative care is provided by health, social, educational and religious institutions. In developed countries, there are different organizational forms of palliative care for children: home, hospice and hospital models, and a combination of the three models [4]. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, children's palliative care is closely related to Children's Clinics, tertiary level of health care, Intensive Therapy Units, as there is not a single form of care for these patients at the level of primary and secondary health care, where these patients legally belong. It is important to emphasize that there is not a single hospice-type institution that would provide care for small pediatric palliative patients. Today, hospice is a philosophical approach and form of care for the dying, and at the same time a modern health institution with a large number of programs to provide assistance to people whose life is approaching the end and to their families/caregivers, and when death occurs as an end, to provide assistance in mourning. It is an institution that provides adequate help and care for the child and his family, from the moment of diagnosis, through death and mourning. Each and every such institution must provide a sense of security and protection to children and parents [5].

Palliative Care for Children

It is necessary to make the distinction between palliative medicine, which relates to the patient's optimal quality of life until death, and is in a doctors' domain, and palliative care, which is carried out by an interdisciplinary palliative team. Palliative medicine acts in three directions: alleviation of symptoms (pain), psychosocial support for the patient, his/her family and caregivers even after the patient's death, and solving ethical problems related to dying [6,7].

The most important goal of curative medicine is to cure the patient, whereby death is considered a failure; in palliative medicine the main objective is relief and reduction of pain and suffering, while death that occurs after all the undertaken treatments is not considered a defeat. Increasing interest in pediatric palliative care occurs after the World Health Organization published the manual "Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care in Children" in 1998 [3]. The World Health Organization's definition of palliative care for children includes many different forms of care with different goals:

- Pediatric palliative care, which includes a holistic approach, begins when the diagnosis is made, takes place during the curative treatment and represents overall care for the psychophysical and spiritual dimensions of the sick child, with the support to family

- Effective palliative care can be provided from the sick child's family home, to hospital institutions, and it requires a multidisciplinary approach which includes the family, experts, volunteers and society's

The goal of palliative care is not to prolong life at any cost, but to achieve the highest possible quality of life, both for the sick child and the members of his/her family.

Categorization of Children in Palliative Care

In developed countries, children requiring palliative care are divided into two large groups: children suffering from malignant and non-malignant diseases. Thanks to the medical science progress, nowadays, a large number of malignant diseases are curable. Non-malignant diseases are divided into neurological diseases, which include children with diseases limiting their daily life by reducing the ability to move, learn; and non-neurological diseases requiring intensive treatment to keep the patient alive. These diseases can endanger the life of the child, without causing death, but they can also be life-limiting with a certain fatal outcome [8].

All these diseases can be classified into four groups:

- Life-threatening diseases with an uncertain outcome (malignant diseases, multiorgan failure),

- Diseases in which premature death is inevitable, but long-term intensive medical treatment can significantly improve and prolong the child's life (cystic fibrosis, congenital cardiovascular anomalies),

- Progressive diseases with no adequate medical treatment (neurodegenerative anomalies, progressive metabolic disorders, muscular dystrophies),

- Irreversible, but not progressive illnesses (cerebral palsy, chromosomal anomalies, child immaturity, genetic anomalies) [9].

Canadian surgeon Balfour Mount, who founded the first palliative department at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal in 1973, is considered the founder of palliative care. The first hospice for children under the name of “Helen House” was founded in 1982 in Oxford by the Anglican nun Frances Dominica Ritchie. According to data from the literature, the number of children requiring palliative care is 10 per 10.000 children. In a population of 50.000 children, five children would die annually, 50 would live with life-limiting illnesses, and 25 would require active palliative care. Most children (72%) die in hospitals, and in other emergency and intensive care units (17%), while 11% of children die in the family home. Infants up to one year of age mostly die in hospitals (75%), while almost all deaths of children during childbirth occur in hospitals (98%). In the majority of cases, hospitalized children die in intensive care units (87%). The cause of death is life- limiting diseases such as: congenital malformations 22%, perinatal diseases 18%, cardiovascular diseases 15% and malignant diseases 12%. These data indicate the necessity of establishing palliative departments (4, 10, 11, 12).

Models of Palliative Care for Children

As children grow up, their perception of reality changes, especially their perception of their illness and death. Thanks to progress in the treatment of certain diseases, more children reach adulthood, and there is a need for developing transitional models from pediatric to adult care.

There are several models of pediatric palliative care:

- A model of determining the child's needs based on classical medicine, taking into account the child's health, his/her physiological needs and difficulties, completely neglecting the spiritual and mental

- A model of palliative care focused on the family of the sick person and their needs, which is based on an agreement between the family and the palliative team, often neglecting the needs of the child itself, especially in adolescence when the child makes key decisions.

- A model of palliative care focused only on the sick child, whereas the family, local community and state institutions are only secondary issue, where the child and his needs and wishes are in the foreground, without adequate integration of the

- A holistic model of pediatric intensive care which is based on several basic principles: every child and his/her family are unique, thus requiring a unique In this way, the child's developmental needs, health, education, emotional and social life, and identity development are met. Parents are able to respond to the child's needs such as basic care, security, protection, love, emotional warmth. No less important is the wider social community and its resources, the place of the family in the community, the employment of parents, etc. [8].

Taking into account the mentioned palliative care models, there are also some special features of institutions in places providing such care: the first model most often refers to hospital departments of children's oncology, with special palliative departments. The second model takes place in hospices, specialized palliative institutions, the third, home model, refers to a specialized palliative team providing care to sick children and support to the family. Home care is provided by palliative care teams, visiting nurses, crisis intervention teams, hospice teams and volunteers of a social community. Consultative care is also being developed through all modern means of communication to be available to children and parents 24 hours a day. Home care usually refers to well developed and organized care at local community level, which includes kindergartens, schools, play groups, groups for parents' break, mourning groups and similar.

The number of children dying in a family environment, as the wish of both children and parents, has significantly increased. In Great Britain that share amounts to 77%, in Canada 44%, Germany 40%, and in Italy only 5%. An increased percentage of children dying in the family environment is the result of an available and developed model of palliative care in the local community. In palliative care, primary care physicians are the main link between sick children, their families and the palliative team. They have been trained in pain management therapies, and can provide the necessary relief from pain and discomfort at home. Thus, the hospitalization of palliative patients can be limited to cases where the technical capabilities of the hospital are of actual benefit to the sick child.

The hospital model provides acute inpatient care, rest and recovery, and a full range of inpatient and specialist services delivered in general, children's and clinical hospitals. Medical treatment involves controlling the resulting complaints, stabilizing the condition, and, if possible, releasing the child home as soon as further care is provided by the family doctor and outpatient palliative care services. Research shows that out of 95% of parents interviewed by medical staff, only 50% understand and accept the fact that their child will not recover [13].

The physical pain of children with life-limiting diseases has many causes and children's perception of pain changes as they grow up and mature. If possible, analgesics should be administered orally, in an individualized procedure, adapted to each patient. The right analgesic should be chosen, in the right dose and at the right time, in order to achieve maximum relief from pain with the least harmful effects. Increasingly, instead of high doses of a mild opioid, small doses of a strong opioid such as morphine are given daily, sometimes continuously. Analgesia with fentanyl patches, lasting for three days, has been used recently. When it comes to neuropathic pain, analgesics, antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs are given. Emotional disorders are alleviated by practicing techniques of behavioral observation, relaxation and suppression of hypersensitivity to pain under the expert supervision of the palliative team. The main thing is simply to be with the sick child and fulfill his/her wishes by listening to what he/she says (squeeze his/her hand, wipe the sweat from his/her forehead, and moisturize dry lips...). A psychiatric symptom is anxiety that often accompanies the last part of a child's life.

It is accompanied by restlessness, tension, insomnia, hyperactivity of the autonomic nervous system. As pain becomes more severe, the duty to relieve suffering becomes greater than the duty not to harm. A special type of palliative care for pediatric patients is a children's hospice. It is a unique institution that provides practical help and emotional support to a sick child and their family from diagnosis to death and the mourning period. The hospice has a family atmosphere, unlike the hospital ward, which is important for the child, their family, but also for the staff working there. The doors of the hospice are open 24 hours a day for the whole family, so the child is never alone. The staff providing care for these patients also provides care for children accommodated in family homes to spend their last days. Hospices provide education for parents, children and volunteers.

These institutions tend to provide an environment of special protection to sick children and their families. Children's hospices provide a break for parents caring for a sick child, and also the necessary emergency intervention for a child accommodated in the family home. These institutions also provide care for children born with congenital malformations with poor prognosis. Given that various problems, not only physical, but also psychological, social and spiritual, occur in the final phase of life, the hospice always has a team of experts from different professions available [14,15].

Pediatric Palliative Care Multidisciplinary Team

Well-functioning palliative care relies to a large extent on comprehensive care provided by a multidisciplinary palliative team of experts consisting of palliative care doctors, doctors of other specialties, caregivers, volunteers, social workers, psychologists, psychotherapists, clergy, physiotherapists, dieticians, and ideally, it also consists of a music and art therapist as part of the team. This team provides important support when a patient moves from a hospital ward to outpatient care, working closely with family physicians and outpatient care services. The role of volunteers, who are part of the palliative team and who as medical laymen have a good will to help people, consists of their longer stay with a sick child during home visits in order to assist the child in reading, talking and playing. It is important for volunteers to undergo training before joining the palliative care team [16,17].

Communication between the Team, Child, Parents and Family

The terminal phase begins when nothing more can be done to improve the child's health, and when death is inevitable. Both doctors and medical staff are overtaken by a feeling of helplessness. Parents often lose faith in medical science and start looking for alternative ways of healing. If there are other children in the family, they are in a very difficult position as the parents are completely devoted to the sick child, and they experience a feeling of guilt. The usual communication of healthcare staff caring for a pediatric palliative patient has an additional component, not only talking with the child but also with the parents. In order to achieve good communication, basic principles must be adhered to. For a successful conversation, it is necessary to ensure suitable conditions.

Therefore it is desirable that only those concerned with the conversation are present in the room, to ensure that the conversation is not interrupted. Good communication with the patient needs to be ensured especially near the end of life. Patience and understanding are needed as that has the greatest influence on the thinking and behavior of parents and children in need of palliative care. It is necessary to pay attention to the basic principles of such communication, specifically that the patients, in this case the parents and the child, want the truth about the diagnosis, that patients are not harmed by talking about the end of life, and that anxiety is normal for both patients and doctors during such conversations.

Tests conducted in order to determine the patient's satisfaction with the health care staff, showed that the largest number of complaints related to dissatisfaction in communication with the health care workers. It is mainly related to the fact that less time is devoted to the conversation, that the patient and parents, respectively do not have sufficient information, due to the use of professional terminology, which parents and especially the child do not understand. No matter how difficult the situation is, it is good to smile when appropriate, and to pay attention to non-verbal communication. It is necessary to introduce yourself to the parents and the child to gain mutual trust at the first meeting. It is always good to get down to the child's level and address him/her by name. The palliative team also provides emotional support, thus a psychologist and/or psychiatrist is an important part of the team. It is important that the staff of the palliative team assess the parents' knowledge about the child's illness and condition. Parents should always be allowed to ask questions. The conversation must be honest and open with concrete advice, without promises that cannot be fulfilled which is the prerequisite for trust and successful cooperation between the palliative team and parents. It should be emphasized that during the entire communication process, the professional barrier must not be crossed, however difficult it may seem in the case of a child in need of palliative care.

Most parents find comfort in the last moments spent with their child, and they should be allowed to do so. There is a specially arranged area in hospices, where parents can spend time with a dying child. That difficult period is followed by the time of mourning, which is also part of palliative care. That involves all kinds of assistance in order for the family to overcome the irreparable loss and survive as a functional family. Parents find it difficult to get back into their daily routine and take responsibility towards the remaining family members. Thus, the work of educated volunteers, psychologists and religious officials is important in this process [16,17].

Our Experiences

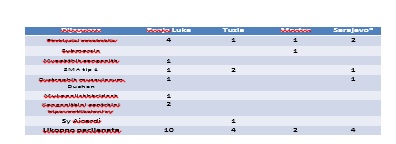

Figure 1: Total number of patients hospitalized in Pediatric Intensive Care Units in 2019.

Figure 1: Total number of patients hospitalized in Pediatric Intensive Care Units in 2019.

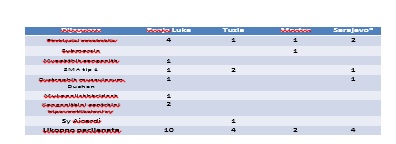

Figure 2: Patients on home mechanical ventilation.

Figure 2: Patients on home mechanical ventilation.

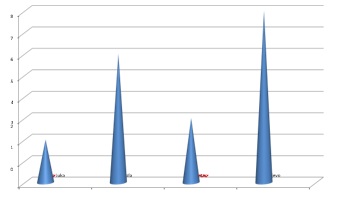

Figure 3: Palliative patients permanently hospitalized in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.

Figure 3: Palliative patients permanently hospitalized in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.

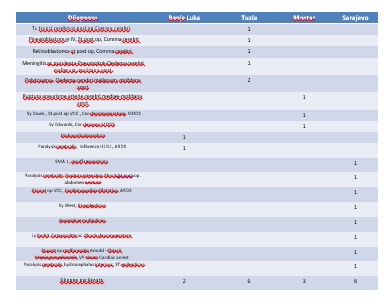

Table 1: The most common reason for long-term (chronic) mechanical ventilation – home mechanical ventilation.

Table 1: The most common reason for long-term (chronic) mechanical ventilation – home mechanical ventilation.

Figure 4: The most common reason for long-term (chronic) mechanical ventilation-home mechanical ventilation.

Figure 4: The most common reason for long-term (chronic) mechanical ventilation-home mechanical ventilation.

Table 2: Palliative patients hospitalized in the ICU, on MV with a basic diagnosis without the possibility of recovery, cure of the basic disease or resulting complications.

Table 2: Palliative patients hospitalized in the ICU, on MV with a basic diagnosis without the possibility of recovery, cure of the basic disease or resulting complications.

Figure 5: Palliative patients hospitalized in the ICU, on MV with a basic diagnosis without the possibility of recovery, cure of the basic disease or resulting complications.

Figure 5: Palliative patients hospitalized in the ICU, on MV with a basic diagnosis without the possibility of recovery, cure of the basic disease or resulting complications.

Discussion

The above presented figures containing data on palliative patients from the four largest pediatric clinics in Bosnia and Herzegovina, show that most palliative patients belong to the group of progressive diseases with no adequate medical treatment (muscular dystrophy, neuro degenerative anomalies, progressive metabolic disorders, as well as irreversible, but not progressive, diseases (cerebral paralysis, chromosomal anomalies). There is a large disparity in patients receiving home treatment and requiring mechanical ventilation; in Banja Luka 10 patients receive palliative care at home, while in Sarajevo all patients requiring chronic ventilation are hospitalized in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. The presented data refer to the year 2019. It was not possible to collect data over the last two years given the different work concept of the Pediatric Clinics due to the COVID 19 pandemic.

Conclusion

Instead of a conclusion, it should be emphasized that the model of palliative care for children worldwide is in the fourth decade of its existence, while there are no signs of attempts to establish children’s' palliative care in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The biggest problem is that there is no defined status of palliative care within the general health insurance system, which entails the issue of financing, making it difficult to establish palliative care units. Since there is no mutual communication between the institutions where these patients are hospitalized, there is a disconnection and insufficient integration of the hospital, home, outpatient clinic, hospice and social organizational model of palliative pediatric care. In our country, which is taking the first steps in accepting the existence of this group of patients, it is necessary to start working on legislation, involving and sensitizing the public, upbringing and education, developing our own integrative model of care adapted to the circumstances in which we live and work, while respecting all positive achievements in the neighboring countries and the world. Palliative care is much more than just relieving pain and other accompanying symptoms. It represents a new form of life philosophy, as it affirms the everlasting value of human life and the dignity of leaving this world. Perhaps, it is one of the harbingers of a new age and a more humane understanding of society in which hope, joy and love should regain their rightful place.

References

- Potts S (2009) The History and Ethos of Palliative Care for Children and Young People. Wiley Online Library: 263.

- Jusic A (2001) Palijativna medicina-palijativna Medicus 10: 247-248.

- https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42001/9241545127.pdf?sequence=1

- Milligran S, Potts S (2009) The History of Paliatice Care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell: 5-6.

- Popovic D, Jušic (2005) Tiha revolucija u medicini. Medix11: 148.

- Stepan-Giljevic J, Butkovic D (2011) Bioeticki aspekti palijativne skrbi u In: Brkljacic-Zagrovic M. Medicinska etika u palijativnoj skrbi. Zagreb: Centar za biotiku: 58.

- WORLD HEALTH Three-Step Ladder.

- Grbavac J, Stajduhar Palijativna skrb za djecu (2012) Rijecki teoloski casopis 40: 269-290.

- Crozier F, Hancock EL (2012) Pediatric Palliative Care: Beyond the end of Pediatric Nursing. 38: 198-227.

- Centeno C, Clark D, Lynch T, Racafort J, Praill D, et al. (2007) Facts and indicators on palliative care development in 52 countries of the WHO European region: results of an EAPC Task Force. Palliat Med. 21: 463-471.

- Bras M, Dordevic V (2013) Palijativna medicina-civilizacijski iskorak. U: Osnove palijativne medicine. Ars medica prema kulturi zdravlja i covjecnosti. Zagreb: Medicinska naklada .

- Radbruch L, Payne S (2009) White Paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe: part Recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. EJPC 16: 278-89.

- Belmore J (2009) Challengs of Providing Paediatric Palliative Care in the Hospital In: Stevens E, Jackson S, Milligrad S. Palliative Nursing: Across the Spectrum Care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell 269-275.

- Brown E (2007) The End of Life Phase of In: Brown E, Warr B. Supporting the Child and the Family in Paediatric Palliative Care. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers 59-66.

- Gold EA (2009) Children's Palliative Care in the Hospice and the Community. In: Stevens E, Jackson S, Milligrad S. Palliative Nursing: Across the Spectrum Care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell 280.

- Lovrek-Senicic M, Kicic M, Karabegovic A (2021) Palijativna skrb u Nastavnicka revija 21:76-87.

- Modrušan H, Turk Paliativna skrb za dijete i obitelj. Strucno informativno glasilo Hrvatskog društva medicinskih sestara anestezije, reanimacije, intenzivne skrbi i transfuzije. S XII;1.

Citation: Misanovic V, Anic D, Catibusic-Hadzagic F, Maksic- Kovacevic H, Dzinovic A, et al. (2022) (Non) Organization of Paliative Care for Children in Bosnia and Herzegovina. J Neonatol Clin Pediatr 9: 095.

Copyright: © 2022 Verica Misanovic, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.