Oral Health Workforce Planning in Nigeria

*Corresponding Author(s):

Hakeem AjaoDepartment Of Oral And Maxillofacial Surgery, Leeds Dental Institute, Leeds, United Kingdom

Tel:+44 7809723752,

Email:Hakeemajao@yahoo.com

Abstract

Few studies have analysed the current oral health personnel situation in Nigeria. However, as Nigeria is facing a shortage of dentists, there is a need to develop more robust data and undertake research into the most appropriate skill-mix to support and inform future workforce planning. This paper maps the current oral health workforce situation in Nigeria and explores the possibility for skill-mix and the contribution to workforce capacity that could be made by dental care professionals, including dental hygienists, therapists and nurses.

Keywords

Dentist; Nigeria; Oral health; Skill-mix; Workforce planning

INTRODUCTION

Workforce planning

Few studies have analysed the current oral health personnel situation in Nigeria. Akande [3], enumerated the gap in the number of dentist in Nigeria. He noted that the oral health needs of the population cannot be met by the 1728 dentist available in 1997; hence, more dentists need to be trained. Aderinokun [4], recognised that the number of dentists in Nigeria was on a decline, proposed and implemented a primary care model for use in Idikan a rural setting in Nigeria. Ogunbodede [5], reviewed the population of dentists in Nigeria and gender differences from 1981-2000 and how this affected the pattern of services delivered. He proposed more dentists to be trained to meet the growing oral health needs of the Nigerian people.

Previous literatures on workforce planning in Nigeria were inconclusive and neither specified the grade, skill and number of oral health care personnel needed in Nigeria.

However, for countries such as Nigeria where health professionals have a cycle of migration to developed countries, it is important to consider the opportunity cost of training oral health professionals who may seek pastures new in developed countries. Also, it is necessary to address local working conditions and design a workforce trained to meet local needs who are less prone to the attractions of migration due to career opportunities, higher salaries or lifestyle [6].

The aim of this paper is to map the current oral health workforce situation in Nigeria and explore the possibility for skill-mix.

Oral health in Nigeria

The prevalence of periodontal pocket is quite high with deep pockets present in a high proportion of young adolescent. Also angles class II and class III malocclusion and traumatic dental injuries have been reported in children below the age of 15 years [9-11]. However, much of this disease is untreated and population growth means that the size of the challenge is increasing.

Recent oral health survey in Nigeria in 2011 involving 7,630 participants ages 18-80 conducted before the introduction of the oral health policy in 2012 reported over 26.4% having visited the dentist at least once while over 50% has never been to a dentist.

A large proportion (more than 70%) of adult Nigerian have periodontal disease and most carious lesion remain untreated [12]. The survey provided a veritable information for the implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the national oral health policy.

Nigeria operates a three-tier health system (federal, state and local government levels) but all health policies are usually made at the federal level. Whilst most developed countries of the world have up-to-date modelling of oral health workforce, a major barrier to improving oral health in Nigeria is the absence of an effective model for oral health care delivery [13].

The dramatic increase in the pattern of oral health diseases in Nigeria in the last forty years has necessitated a shift in the way the profession and government respond to the size, shape and skill mix necessary to meet the insatiable demand for dental care. This is supported by the report of shortage of dentists and oral health care workers to meet the dental care needs of the growing dissatisfied public [7,8,12]. There is the need to plan, train, develop and utilize frontline oral health worker of various types due to the role they play within the total health care of the nation [14]. The planning of oral health workforce should be integral part of the general health planning system especially in a developing economy like Nigeria because it has policy decision implications.

To bolster the need for adequate workforce planning in Nigeria, the Oral Health Policy (OHP) was developed and finally adopted in 2012 through multi-stake holder participation of experts in oral health [15]. The OHP is intended to achieve optimal oral health care for Nigerians with a population of one hundred and eighty-two million people (Table 1).

|

Age-Group |

% by Age-Band |

Population in 000s |

|||

|

2017 |

2022 |

2027 |

2032 |

||

|

0-14 |

42% |

71,500 |

74,500 |

78,000 |

82,000 |

|

15-29 |

25% |

44,500 |

48,500 |

51,000 |

53,000 |

|

30-64 |

25% |

54,500 |

57,500 |

61,000 |

65,000 |

|

65+ |

8% |

11,500 |

14,500 |

17,677 |

20,000 |

|

Total |

100% |

182,000 |

195,000 |

207,677 |

220,000 |

METHODS

Workforce planning models

WHO/FDI model

System dynamics model

Dentist-to-population ratio

Scenario planning

Due to the limitations of the other workforce planning tool and its overdependence on the use of dentists for providing oral health care, operational research using scenario planning will be used to explore the number of hygienists, therapists and nurses, needed for Nigeria now and in the future (2022, 2027, 2032 and 2037).

Recent work in Wales by Evans et al. [27], suggests that therapists or hygienists can perform 43% of time taken to provide care by dentist while the dentist can provide the rest of the clinical time (57%). Using operational research planning and combining the findings of Evans et al. [27], with additional scenario planning can be used to explore the development of a locally more appropriate workforce.

RESULTS

Data collection

Demand model

|

Epidemiology |

Population |

Prevalence |

Age |

|

Caries |

5714 |

4-30% (DFMT=0.6) |

6-20 |

|

Periodontitis |

2230 |

15-58% |

15-40 |

|

Traumatic dental lesions |

1401 |

11-30% |

10-15 |

|

Orthodontic treatment |

1394 |

8-15% |

10-19 |

|

Oral health survey |

7630 |

26.4% |

18-80 |

|

National survey |

4692 |

N/A |

12-15 |

N/A=Not Available

DFMT=Decayed Missing and Filled Teeth

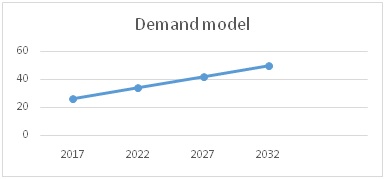

The demand model was estimated based on the last oral health survey in Nigeria in 2011 involving 7,630 participants ages 18-80 conducted before the introduction of the oral health policy in 2012 which reported over 26.4% having visited the dentist at least once while over 50% has never been to a dentist (Table 2). Estimated demand for oral health care was about 25% to 50% of the population of Nigerians (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Projected demand model.

• Demand for oral care as a percentage of population

• Demand for oral care is estimated based on reported uptake of treatment

• Demand for oral health care will increase with population increase

Supply model

In Nigeria there are about 4060 dentists, 1220 therapists, 1540 dental nurses, 500 dental hygienists (Table 3). There are nine accredited dental schools located in Nigeria, two schools of dental therapy and hygienist and eight dental nursing schools [29].This is due to poor conditions of services and exodus to developed countries for pastures new. There is need in the future for the number of dental care professional to increase.

|

Professionals |

2017 |

2022 |

2027 |

2032 |

|

Dentists |

4,060 |

5,290 |

6,090 |

6960 |

|

Dentists (Minus 20% due to migration and death)* |

||||

|

Dental therapists |

1,220 |

1,370 |

1,520 |

1,670 |

|

Dental nurses |

1,540 |

1800 |

2,140 |

2,440 |

|

Hygienists |

500 |

600 |

780 |

880 |

|

Total dental professionals involved in clinical care |

7,320 |

9060 |

10,530 |

11950 |

*Average loss of dentists due to migration, death and retirement.

• Calculation of dentists, dental therapists, hygienists, nurses are based on the present oral health workforce and those in training

A total of 446 dental clinics and hospitals presently provide oral health care services across the country [31]. The management of these facilities is influenced by their funding lines, which may derive from government (federal or state), private, corporate or faith-based bodies. Most of dental facilities are in cities and towns. Only 20% of dentists in both the private and public sectors work in rural areas, where more than half of the population reside [5].

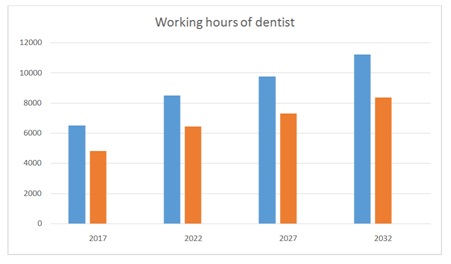

Blue=Dentist work full time 1600 hours per annum

Red=Dentist work part time 1200 hours per annum

Blue=Hygienist work full time 1600 hours per annum

Red=Therapist work full time 1600 hours per annum

Grey=Dental nurses work full time 1600 hours per annum

Education and training

The training lasts for 5-6 years depending on the year of entry. Six years for those entering straight from secondary schools through a university matriculation examination and 5 years for those with a levels or first degree. A total of 200 dentists are produced annually [29].

The National Dental Therapist’s Board is responsible for accreditation of dental therapists and hygienists [32]. These groups are involved in advocacy for oral health in the country and have been actively involved in clinical duties which include scaling and polishing, curettage and root planning and dressing of periodontal pocket. They do not perform extraction. About 40 dental hygienists and 30 therapists are trained each year.

The National Board for Technical Education regulates the award of diplomas from the eight dental nursing schools in Nigeria. The dental nurses’ role involves assisting the dental surgeon in all procedures and work that is carried out. This includes oral hygiene instructions and motivation and all other work as prescribed under the supervision of the dentist. About 100 nurses are trained each year [33].

Demand supply gap

Workforce skill-mix

Scenario 1

Scenario 2

Red=Dentist supply

Grey=Using Hygienist, Therapist and Nurse to do 43% role of dentist

Dentists, Hygienists, Therapist and Nurses working full time.

DISCUSSION

The changing disease trends in the last four decades has corroborated the need to utilize the hygienists, therapists and dental nurses for expanded roles in meeting the oral health demands of Nigerians. Using scenario planning to explore skill mix: hygienists, therapists and nurses could potentially reduce the number of dentist required if 43% of dentist job are delegated to them (Figure 3). However, they would need to work full time (1600 hours) to potentially contribute 20% of the activity required to meet the current reported oral health demand of the population.

However, in 2022 with increasing population about 19,500 full time dentists will be required. Hygienist, therapist and dental nurses could potentially increase the oral health workforce if given expanded role. They can be utilized in the rural areas to meet the oral health demands of the population.

As oral health services demand is expected to grow commensurately with population growth as seen in developed countries like Australia [35]. There is therefore the need to expand the oral health workforce to meet the required number. The implication is that more funds needs to be allocated for manpower training, development and research. Also, consideration needs to be given to the training of hygienists, therapists and nurses as their training require a shorter period. The time taken to train dentists is 5 or 6 years while hygienists and therapists can be trained in 3 years.

Strengths and limitations of this research

The limitations identified in this study have been identified in the literature; first, it focuses only on the use of dentists for providing oral health care [23]; second, there is no recognition of the geographic spread of dental manpower between urban and rural areas [3,4,38]; third, it depends on robust data for accurate workforce modelling which are not readily available [3-5]; fourth, the sparse or non-existent literature on workforce planning on which to build [3,4,13].

Using scenario planning and drawing on other research findings, this enabled consideration of the role that hygienists, therapists and nurses may play in dental care. Mindful of the fact that clinical dental care in Nigeria will be very different to the UK where the original research was undertaken and that dentists and hygienists/therapists do not work at the same rate, the use of these skill-mix scenarios can contribute by identifying the optimum numbers of the mix of health workers needed for oral health care. However, this reveals the fifth limitation of the study, the absence of information on appropriate ‘task-shifting’, which has significant potential for Nigeria and innumerable political, financial and social implications, the complexity of which has been outlined by Lehmann [34,39].

Contribution to knowledge

CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

REFERENCES

- Ettelt S, Nolte E, Thompson S, Mays N (2008) Capacity planning in health care: Reviewing the international experience. Euro Observer 9: 1-5.

- Buchan J, Dal Poz MR (2002) Skill mix in the health care workforce: Reviewing the evidence. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 80: 575-580.

- Akande OO (2004) Dentistry and medical dominance: Nigerian perspective. Afr J Biomed Res 7.

- Aderinokun GA (2000) Review of a community oral health programme after ten years. Afr J Biomed Res 3: 123-128.

- Ogunbodede EO (2002) Gender distribution of dentists in Nigeria, 1981-2000. Journal Dental Education 68: 15-21.

- Dovio D (2005) Taking more than a fair share? The migration of health professionals from poor to rich countries. PLoS Med 2: 109.

- Akpata ES (2004) Oral health in Nigeria. Int Dent J 54: 361-366.

- Adegbembo AO, El-Nadeff MAI, Adeyinka A (1995) National survey of dental caries status and treatment need in Nigeria. Int Dent J 45: 35-44.

- Isikwe MC (1983) Malocclusion in Lagos, Nigeria. Community Dental Oral Epidemiol 11: 59-62.

- Adekoya-Sofowora C, Buraimah R, Ogunbodede E (2006) Traumatic dental injuries experience in suburban adolescent. The Internet Journal of Dental Science 5.

- Onyeaso CO, Utomi IL, Ibekwe TS (2005) Emotional effects of malocclusion in Nigerian orthodontic patients. J Contemp Dent Pract 6: 64-73.

- Olusile AO, Adeniyi AA, Orebanjo O (2014) Self- rated oral health status, oral health service utilization, oral hygiene practices among adult Nigerians. BMC Oral health 14: 140.

- Ajao H (2008) Meeting the Oral health needs of the population of Nigeria. Workforce implications, London, UK.

- Jeboda SO (1989) Manpower training, development and utilization in primary oral health care. A suggested approach for Nigeria. Odontostomatology Tropicale 12: 130-134

- Etiaba E, Uguru N, Ebenso B, Russo G, Ezumah N, et al. (2015) Development of oral health policy in Nigeria: An analysis of the role of context, actors and policy process. BMC Oral Health 15: 56

- Bourgeois D, Leclercq MH, Barmes DE, Dieudonné B (1993) The application of the theoretical model WHO/FDI planning system to an industrialised country: France. Int Dent J 43: 50-58.

- World Health Organisation (1989) Health through oral health. Guidelines for planning and monitoring for oral health: Joint WHO/FDI working group 362. Quintessence, Chicago, USA.

- Bronkhorst EM, Wiersma T, Truin GJ (990) Using complex system dynamics model: An example concerning the Dutch dental health care system: International system dynamics conference system. Dynamics Society 1: 155-163.

- Schreuder RF (1995) Health scenarios and policy making: Lessons from the Netherlands. Futures 27: 953-958.

- Godet M (1987) Scenario and strategic management. Butterworth, California, USA.

- Burgersdijk R, Brokhurst E, Truin G (1994) Future scenarios on dental health care: A reconnaissance of the period 1990-2020. Kluwer Academic Publishers, London, UK.

- Gallagher J (2008) Dental Professionals. In: Heggenhougen K, Quah S, (eds.). Encyclopedia of Public Health. San Diego Elsevier, California, USA.

- Morgan M.V, Wright FAC, Lawrence AJ, Laslett AM (1994) Workforce predictions: A situation analysis and critique of the World Health Organisation model. International Dental Journal 44: 27-32.

- Forrester JW (1969) Urban Dynamics. MIT Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Rodrigues AG, Williams TM (1998) System Dynamics in project management: Assessing the impacts of client behaviour on project performance. Journal of the Operational Research Society 49: 2-15.

- Goodman HS, Weyant RJ (1990) Dental personnel planning: A review of literature. American Journal of Public Health Dentistry 50: 48-63.

- Evans C, Chestnutt IG, Chadwick BL (2007) The potential for delegation of clinical care in general dental practice. Br Dent J 203: 695-699.

- World Health Organisation (2006) Country health system fact sheet 2006: Nigeria. World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria (2017) Register of Dentists. Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria.

- Azeez B, Anya I, Akeredolu P, Albert O (2008) Worker migration. BDJ 204: 477-488.

- Adeniyi AA, Sofola OO, Kalliecharan RV (2012) An appraisal of the oral health care system in Nigeria. Int Dent J 62: 292-300.

- National Dental Therapists Board (2017) Federal Ministry of Health. National Dental Therapists Board, Abuja, Nigeria.

- National Board for Techical Education (2017) Federal Ministry of Health. National Board for Techical Education, Abuja, Nigeria.

- Fulton BD, Scheffler RM, Sparkes SP, Auh EY, Vujicic M, et al. (2011) Health workforce skill mix and task shifting in low income countries: A review of recent evidence. Hum Resour Health 9: 1.

- Health Workforce Australia (2014) Australia’s future health workforce - Oral health. Health Workforce Australia, Canberra, Australia.

- Odusanya OO, Nwawolo CC (2001) Career aspirations of house officers in lagos Nigeria. Medical Education 35: 482-487.

- Federal Ministry of Health (2015) National Oral Health Budget Abuja. Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria.

- Orenuga O, Da Costa O (2006) Characteristics and study motivation of clinical dental students in Nigerian Universities. J Dent Educ 70: 996-1003.

- Lehmann U, Van Damme W, Barten F, Sanders D (2009) Task shifting: The answer to the human resources crisis in Africa? Hum Resour Health 7: 49.

Citation: Ajao H (2018) Oral Health Workforce Planning in Nigeria. J Otolaryng Head Neck Surg 4: 018.

Copyright: © 2018 Hakeem Ajao, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.