Journal of Non Invasive Vascular Investigation Category: Clinical

Type: Case Report

Patent Ductus Arteriosus Pseudoaneurysm Following Prior PDA Closure: Case Report and Literature Review

*Corresponding Author(s):

Iden AndachehAssistant Clinical Professor, UC Riverside School Of Medicine, Vice-Chairman, General Surgery, Riverside Community Hospital, California, United States

Email:Amarseen.Mikael@hcahealthcare.com

Received Date: Mar 24, 2019

Accepted Date: Apr 08, 2019

Published Date: Apr 15, 2019

Abstract

Background: Pseudoaneurysm developing after repair of a Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA) is uncommon, with only a handful of cases reported in the literature. While older literature cites infection, recent series suggest formation of pseudoaneurysm off of a ligated PDA attributed to breakdown in the suture line. Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair (TEVAR) for this rare pathology has been demonstrated in selected case reports.

Methods/Results: A 61 year-old woman presented with enlarging Left chest mass and shortness of breath. The patient reported a history of a PDA with two attempts at closure. At age 6, she had undergone an attempt at endovascular closure of the PDA; this subsequently resulted in right lower extremity limb ischemia with resultant below-knee amputation. At age 12, she underwent open thoracotomy with ligation of the PDA; at this procedure, she suffered injury to her recurrent laryngeal nerve, resulting in permanent hoarseness of voice.

A Computed Tomography Angiogram (CTA) of the chest was obtained which demonstrated a saccular 4.5 x 3.8 cm pseudoaneurysm in the region of the PDA with calcify wall changes. Recommendation was made to proceed with operative repair and she agreed. A TEVAR was performing using a commercially-available stent graft. During the procedure, Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS); however, the connection between the PDA pseudoaneurysm and the aorta was not visualized. She had an uncomplicated operative and post-operative course. Follow-up imaging showed complete thrombosis of the pseudoaneurysm.

Conclusion: Pseudoaneurysm from previous PDA repair is a rare pathology. We present a unique case in which the patient had undergone attempts at both endovascular and open surgical repair. Open repair for PDA is still advocated; however, TEVAR appears to be a safe treatment in adults with this pathology following failed open closure. CT imaging provides the best evaluation for PDA pseudoaneurysm in terms of diagnosis and operative planning when compared to invasive modalities such as IVUS.

Methods/Results: A 61 year-old woman presented with enlarging Left chest mass and shortness of breath. The patient reported a history of a PDA with two attempts at closure. At age 6, she had undergone an attempt at endovascular closure of the PDA; this subsequently resulted in right lower extremity limb ischemia with resultant below-knee amputation. At age 12, she underwent open thoracotomy with ligation of the PDA; at this procedure, she suffered injury to her recurrent laryngeal nerve, resulting in permanent hoarseness of voice.

A Computed Tomography Angiogram (CTA) of the chest was obtained which demonstrated a saccular 4.5 x 3.8 cm pseudoaneurysm in the region of the PDA with calcify wall changes. Recommendation was made to proceed with operative repair and she agreed. A TEVAR was performing using a commercially-available stent graft. During the procedure, Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS); however, the connection between the PDA pseudoaneurysm and the aorta was not visualized. She had an uncomplicated operative and post-operative course. Follow-up imaging showed complete thrombosis of the pseudoaneurysm.

Conclusion: Pseudoaneurysm from previous PDA repair is a rare pathology. We present a unique case in which the patient had undergone attempts at both endovascular and open surgical repair. Open repair for PDA is still advocated; however, TEVAR appears to be a safe treatment in adults with this pathology following failed open closure. CT imaging provides the best evaluation for PDA pseudoaneurysm in terms of diagnosis and operative planning when compared to invasive modalities such as IVUS.

BACKGROUND

Pseudoaneurysm developing after repair of a Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA) is extremely uncommon, with only a handful of cases reported in the literature. While older literature cites infection, recent series suggest formation of pseudoaneurysm off of a ligated PDA attributed to breakdown in the suture line or creation of a stenotic ductus [1]. Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair (TEVAR) for this rare pathology has been demonstrated in selected cases [2,3]. We present a unique case of a pseudoaneurysm after patient had undergone two attempts at prior PDA closure via an endovascular and open approach.

METHODS/RESULTS

A 61 year-old woman presented with enlarging Left chest mass and shortness of breath. The patient reported a history of a PDA with two attempts at closure. At age 6, she had undergone an attempt at endovascular closure of the PDA; this subsequently resulted in right lower extremity limb ischemia with resultant below-knee amputation. At age 12, she underwent open thoracotomy with ligation of the PDA; at this procedure, she suffered injury to her recurrent laryngeal nerve, resulting in permanent hoarseness of voice.

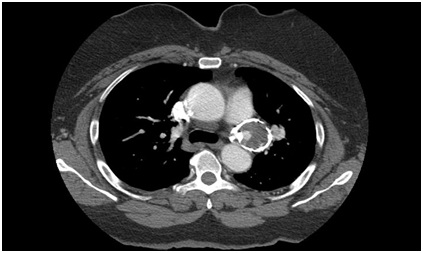

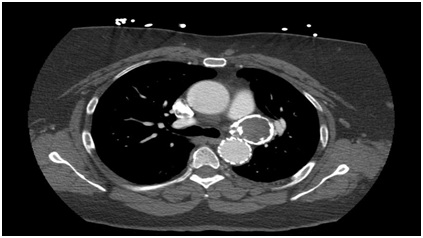

A Computed Tomography Angiogram (CTA) of the chest was obtained which demonstrated a saccular 4.5 x 3.8 cm pseudoaneurysm in the region of the PDA with calcific wall changes (Figure 1). The pseudoaneurysm enhanced on arterial phase. On prior CT imaging a year prior, the pseudoaneurysm measured 4.1 cm x 3.5 cm. Given her symptoms, pseudoaneurysm growth, and unknown natural history of these pseudoaneurysms, the recommendation was made to proceed with operative repair.

A Computed Tomography Angiogram (CTA) of the chest was obtained which demonstrated a saccular 4.5 x 3.8 cm pseudoaneurysm in the region of the PDA with calcific wall changes (Figure 1). The pseudoaneurysm enhanced on arterial phase. On prior CT imaging a year prior, the pseudoaneurysm measured 4.1 cm x 3.5 cm. Given her symptoms, pseudoaneurysm growth, and unknown natural history of these pseudoaneurysms, the recommendation was made to proceed with operative repair.

Figure 1: Preoperative CT showing PDA pseudoaneurysm with intraluminal flow.

Given her two prior surgeries and resulting complications, the patient was understandable very reluctant to proceed with surgical repair. Extensive discussion was had with her and her husband, with recommendation made for TEVAR. After the patient considered her options, she agreed to proceed with this intervention.

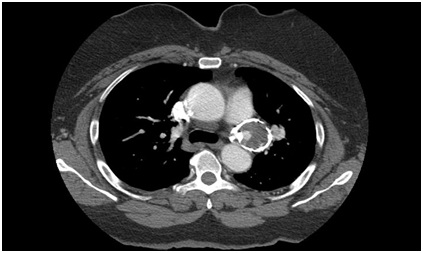

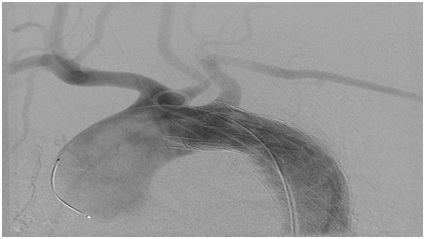

The patient underwent TEVAR via percutaneous access of the Left common femoral artery (Figure 2). A single GORE (Flagstaff, Arizona) 34 mm x 10 mm graft was placed distal to the Left subclavian artery. She did have complaint of chest pain and back pain on POD #1, but imaging showed no complications and complete thrombosis of the PDA pseudoaneurysm (Figure 3). In the follow-op period, she had complete resolution of the chest and back pain.

Figure 2: Deployed aortic stent graft distal to Left Subclavian Artery (LSA).

Figure 3: Postoperative CT showing thrombosis PDA pseudoaneurysm.

DISCUSSION

Patent ductus arteriosus is typically discovered during childhood or infancy and subsequently treated at that time. Historically, the treatment of choice for closure of a PDA was through an open surgical approach with suture ligation of the PDA [4]. In some cases, the open approach carries risk for the patient given that cardiopulmonary bypass with deep hypothermic circulatory arrest may be required. The dissection can also be complicated by injury to local structures; such as the recurrent laryngeal nerve in the case of our patient. Older patients undergoing PDA repair are exposed to greater risks given that they are more likely to already have underlying cardiopulmonary co-morbidities and calcified arteries.

More recently, less invasive endovascular techniques have been utilized in the closure of PDA. The St. Jude amplatzer duct occluder (Saint Paul, MN) is the preferable option for moderate sized PDAs of 4-10 mm. It offers a high success rate (97-99%) and complete closure rates of 98-100%. However, for PDA’s that are smaller than 4mm, coil embolization is preferable given that placement of the plug device in such a small diameter could cause potential dissection or rupture. If the diameter of the PDA is larger than 10-12 mm, the plug device has a risk of migration [5].

An alternative to the amplatzer ductoccluder is coil embolization of the PDA. The complete occlusion rate with coils immediately after the procedure ranged from 58% to 80% and increased to 87-95% in the follow up period. Coil embolization does have some potential disadvantages such as distal embolization of coils and high failure rate in closing large ductus. There was reported 5-20% incidence of distal embolization following release of the coils. In the literature, 3-11% of patients undergoing coil embolization required a secondary intervention. Patients that were younger and who had a larger ductus were more likely to experience these complications and require further intervention [6]. These findings correlate with our patient’s history of distal embolization with resultant below-knee amputation at a young age.

Newer strategies were developed to counter-act some these potential complications arising from coil embolization of a PDA. The modified Grifka method, which utilizes .052-inch coils, which offer better positioning during coil implantation due to the ability of the coil to maintain its tightly wound loop size and configuration resulting in less longitudinal stretch. This strategy resulted in less complication during coil embolization in PDA>2.5 mm and contributed to better outcomes in coil embolization of PDA>4 mm [7]. Despite these newer strategies and techniques, the amplatzer duct occluder appears to be the superior device in transcatheter PDA closure. There is less associated morbidity and near 100 percent PDA closure rate as opposed to coiling methods [8].

A post-operative pseudoaneurysm is a rare but potentially serious complication from PDA closure. Only case reports are available on literature review, most of which are from suture ligation of PDA. Case reports of pseudoaneurysm after transcatheter closure of PDA have also been observed. It is theorized that flow limiting stenosis from incomplete closure leads to arterial dilatation and pseudoaneurysm formation. Given the rarity of the condition, the exact natural history of a PDA pseudoaneurysm is not known. However, the pseudoaneurysm can enlarge and cause compressive symptoms such as chest or back pain, dysphagia, dyspnea, coughing, stridor, and hoarseness. The risk of rupture remains the most lethal potential complication.

An infectious etiology has also been postulated as a potential cause of PDA aneurysm formation. It is hypothesized that an infectious process involving the arterial wall could lead to an overflow in the pulmonary artery, which can then increase the predisposition for mycotic aneurysm formation [9]. Case reports have demonstrated evidence of pulmonary artery aneurysm arising from the site of vegetation located at the area of PDA jet inflow [10].

Historically, infection leading to bacterial endocarditis has been described as one of the highest morbidity complications associated with a PDA pseudoaneurysm after ductus closure. It is unknown, however, if the infective process preceded the operative intervention or was a result from it. No causal relationship has been established between infective endocarditis and recanalization of the PDA leading to a pseudoaneurysm.

More recently, less invasive endovascular techniques have been utilized in the closure of PDA. The St. Jude amplatzer duct occluder (Saint Paul, MN) is the preferable option for moderate sized PDAs of 4-10 mm. It offers a high success rate (97-99%) and complete closure rates of 98-100%. However, for PDA’s that are smaller than 4mm, coil embolization is preferable given that placement of the plug device in such a small diameter could cause potential dissection or rupture. If the diameter of the PDA is larger than 10-12 mm, the plug device has a risk of migration [5].

An alternative to the amplatzer ductoccluder is coil embolization of the PDA. The complete occlusion rate with coils immediately after the procedure ranged from 58% to 80% and increased to 87-95% in the follow up period. Coil embolization does have some potential disadvantages such as distal embolization of coils and high failure rate in closing large ductus. There was reported 5-20% incidence of distal embolization following release of the coils. In the literature, 3-11% of patients undergoing coil embolization required a secondary intervention. Patients that were younger and who had a larger ductus were more likely to experience these complications and require further intervention [6]. These findings correlate with our patient’s history of distal embolization with resultant below-knee amputation at a young age.

Newer strategies were developed to counter-act some these potential complications arising from coil embolization of a PDA. The modified Grifka method, which utilizes .052-inch coils, which offer better positioning during coil implantation due to the ability of the coil to maintain its tightly wound loop size and configuration resulting in less longitudinal stretch. This strategy resulted in less complication during coil embolization in PDA>2.5 mm and contributed to better outcomes in coil embolization of PDA>4 mm [7]. Despite these newer strategies and techniques, the amplatzer duct occluder appears to be the superior device in transcatheter PDA closure. There is less associated morbidity and near 100 percent PDA closure rate as opposed to coiling methods [8].

A post-operative pseudoaneurysm is a rare but potentially serious complication from PDA closure. Only case reports are available on literature review, most of which are from suture ligation of PDA. Case reports of pseudoaneurysm after transcatheter closure of PDA have also been observed. It is theorized that flow limiting stenosis from incomplete closure leads to arterial dilatation and pseudoaneurysm formation. Given the rarity of the condition, the exact natural history of a PDA pseudoaneurysm is not known. However, the pseudoaneurysm can enlarge and cause compressive symptoms such as chest or back pain, dysphagia, dyspnea, coughing, stridor, and hoarseness. The risk of rupture remains the most lethal potential complication.

An infectious etiology has also been postulated as a potential cause of PDA aneurysm formation. It is hypothesized that an infectious process involving the arterial wall could lead to an overflow in the pulmonary artery, which can then increase the predisposition for mycotic aneurysm formation [9]. Case reports have demonstrated evidence of pulmonary artery aneurysm arising from the site of vegetation located at the area of PDA jet inflow [10].

Historically, infection leading to bacterial endocarditis has been described as one of the highest morbidity complications associated with a PDA pseudoaneurysm after ductus closure. It is unknown, however, if the infective process preceded the operative intervention or was a result from it. No causal relationship has been established between infective endocarditis and recanalization of the PDA leading to a pseudoaneurysm.

CONCLUSION

Pseudoaneurysm from previous PDA repair is a rare pathology. We present a unique case in which the patient had undergone attempts at both endovascular and open surgical repair. Given the risks of open surgery and the limitation of transcatheter closure devices in large diameter PDAs, aortic stent grafting appears to be a viable treatment option for closure PDA pseudoaneurysm. As in our patient, an aortic stent graft can also be employed to close pseudoaneurysms from PDAs that have been previously intervened either through open or endovascular techniques. Open repair for PDA is still advocated; however, TEVAR appears to be a safe bail-out treatment in adults with a PDA pseudoaneurysm following failed open or embolization closure. In our experience, we found that non-invasive CT imaging was invaluable for the endovascular repair of this particular pathology.

REFERENCES

- Malhotra A, Gupta S, Kaushal RP, Sharma P, Moolchand S (2013) Aneurysm following ligation of patent ductus arteriosus: Myth or reality? Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 21: 85-87.

- Hua L, Tao Y, Jun W, Weida Z (2013) Successful stent for a pseudoaneurysm after the patent ductus arteriosus closure procedure Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 17: 1038-1039.

- Fujii K, Saga T, Kitayama H, Nakamoto S, Kaneda T, et al. (2012) Successful closure of a patent ductus arteriosus using an aortic stent graft. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 18: 71-74.

- Ross R, Feder F, Spencer F (1961) Aneurysms of Previously Ligated Patent Ductus Arteriosus. Circ J 350-357.

- Tatuishi W, Kataoka G, Asano R, Sato A, Nakano K (2016) Use of Stent Graft for Patent Ductus Arteriosus in an Octogenarian Eliminates Ductus Flow. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 22: 193-195.

- Wang JK, Hwang JJ, Chiang FT, Wu MH, Lin MT, et al. (2006) A strategic approach to transcatheter closure of patent ductus: Gianturco coils for small-to-moderate ductus and Amplatzer duct occluder for large ductus. Int J Cardiol 106: 10-15.

- Tomita H, Takamuro M, Fuse S, Horita N, Hatakeyama K, et al. (2006) Coil occlusion of Patent ductus arteriosus. Circ J 70: 28-30.

- Sheridan BJ, Ward CJ, Anderson BW, Justo RN (2013) Transcatheter closure of the patent ductus arteriosus: an intention to treat analysis. Heart Lung Circ 22: 428-432.

- Song S, Kim SP, Choi JH, Lee HC, Park K (2013) Hybrid approach for aneurysm of patent ductus arteriosus in and adult. Ann Thorac Surg 95: 15-17.

- Kaini A, Radmehr H, Shabanian R (2008) Pulmonary artery aneurysm in a child secondary to infective endarteritis. Pediatr Cardiol 29: 471-472.

Citation: Mikael A, Andacheh I, Yufa A, Nurick H (2019) Patent Ductus Arteriosus Pseudoaneurysm Following Prior PDA Closure: Case Report and Literature Review. J Non Invasive Vasc Invest 4: 015.

Copyright: © 2019 Iden Andacheh, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

© 2026, Copyrights Herald Scholarly Open Access. All Rights Reserved!