Patient Dropout from Opioid Substitution Treatment

*Corresponding Author(s):

Akhtar SDepartment Of Psychiatry, Waikato District Health Board, Hamilton, New Zealand

Email:akif_sohail@xtra.co.nz

Abstract

Opioid Substitution Treatment (OST) is an established treatment for opioid dependence. In New Zealand, OST programmes are regulated by the Ministry of Health (2014) and Methadone and Buprenorphine/Naloxone (Suboxone) are the primary medications. Retention on OST is a key indicator for stabilization of patients with opioid dependence. The purpose of the present research was to study dropout rates and identify factors associated with the dropout of patients from OST at the Community Alcohol and Drug Service (CADS), Hamilton, from 1st January 2013 to 30th April 2014. A retrospective clinical audit of patients on OST was conducted. There were 150 patients on OST in Hamilton under the CADS team during the period of study. Nine patients dropped out during the study period. Sixty-four patients were randomly selected from the remaining 141 patients who remained on treatment as a comparison group and for the study sample to be approximately half of the overall population of 150 patients. File review was conducted and potential predictors of dropout were identified. Thirty-five independent variables were selected and dropout was the dependent variable. The statistical programme SPSS22 was used to analyse the data. Fisher’s exact test was used and four variables were identified as being associated with dropout: history of intravenous drug use; (Fisher’s exact p = 0.05); history of lifetime imprisonment (Fisher’s exact p =0.05); other medications prescribed, (Fisher’s exact p = 0.04); and opioid type prescribed during the study, i.e. methadone or Suboxone. Patients on Suboxone dropped out more than those on methadone, (Fisher’s exact p = 0.00). The overall dropout rate was 6%, which was less than the rates of 15-85% found in previous studies. The limitations of the study were that it was retrospective and the number of dropouts was small. Furthermore, only patient factors associated with dropout were included in the study and service factors were not included.

INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Opioid Substitution Treatment (OST) has been an evidence-based treatment for opioid dependence since the 1960s, when Drs Vincent Dole and Marie Nyswander started using methadone as an OST [1]. The advantages of OST have been well documented in the literature. Retention on OST is considered one of the success criteria of OST. It decreases the harm to patients and society. [2,3] reported methadone maintenance treatment as an effective method for decreasing heroin use. There has been varied evidence of association between psychiatric [4] co morbidities and retention on OST. Found that psychiatric comorbidity was associated with early dropout [5]. Reported a retention rate of over 50% after 12 months on methadone maintenance treatment [6]. Factors associated with higher levels of retention included male gender, treatment setting and methadone dose. Unfortunately the factors associated with retention in one study have not always done so in others. Variables that consistently predict retention across different studies have yet to be identified [7]. For the purpose of this study, a number of terms should be defined. Opioid dependence is defined using the classification system of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of American Psychiatric Association - Fourth Edition, text revision [8].

Definition of dropout from OST

For the purpose of this study, dropout is defined as discontinuation of OST treatment by a patient for at least one month, against medical advice. Dropout is considered a failure of treatment.

Definition of retention

For the purpose of this study retention is defined as remaining on the OST during the study period of 15 months.

METHODS

The period of study was 1 January 2013 to 30 April 2014. The target population was 150 patients on OST under the care of the Community Alcohol and Drug Service, Hamilton. Nine patients dropped out during the study period. Sixty-four patients were randomly selected from the remaining 141 patients who did not drop out from the programme during the study period as a comparison group to ensure the study sample was approximately half of the overall population of 150 patients being treated during the study period. File review was conducted to identify the potential predictive factors for dropout.

Clinical Audit Tool Developed for the Study

From the file reviews of the patients on OST, thirty-five independent variables were identified for the study and a clinical audit tool was developed to collect the data. For descriptive purposes, independent variables were divided into three main groups - demographic variables, history variables, and variables related to medications prescribed and urine drug results during the study. The full list of variables is as follows:

Demographic Variables:

- Age of the patient at dropout

- Gender

- Ethnicity

- Relationship Status

- Employment

- Benefit Status

- Living Status

History Variables:

- History of Imprisonment

- History of Mental Illnesses

- History of Substance Use Disorders between 1 Jan 2013 and 30 April 2014

- History of Partner’s Drug Use

- History of Intravenous (I/V) Drug use

- History of Hospitalisation for Alcohol and Drug Treatment between 1 Jan 2013 and 30 April 2014

- History of Hospitalisation for medical conditions related to I/V drug use between 1 Jan 2013 and 30 April 2014.

- Dose of methadone on 1 January 2013.

- Highest dose of methadone after 1 January 2013.

- Dose of methadone on 30 April 2014.

- Dose of Suboxone on 1 January 2013.

- Dose of Suboxone after 1 January 2013.

- Dose of Suboxone on 30 April 2014.

- Were any benzodiazepines prescribed on 1 January 2013?

- Were any benzodiazepines prescribed after 1 January 2013?

- Were any benzodiazepines prescribed on 30 April 2014?

- Were any other psychotropic medications prescribed on 1 January 2013?

- Were any other psychotropic medications prescribed after 1 January 2013?

- Were any other psychotropic medications prescribed on 30 April 2014?

- Were any other medications prescribed on 1 January 2013?

- Were any other medications prescribed on 30 April 2014?

- Did the patient drop out of OST?

- Urine drug results in January 2013.

- Urine drug results after January 2013.

- Urine drug results in April 2014.

- History of medical conditions.

- History of Hepatitis C infection between 1 January 2013 and 30 April 2014.

- Did the patient receive treatment for Hepatitis C before 30 April 2014?

Dose of Methadone: High dose of methadone was 60 mg and above and low dose of methadone was under 60 mg for this study. 60 mg of methadone was considered the therapeutic dose. In previous study by Retention in methadone treatment was 61% in the study by [9].

Dose of Suboxone: High dose of Suboxone was 16 mg and above and lower dose was under 16 mg for this study. 16 mg of Suboxone was considered the therapeutic dose.

Benzodiazepines prescribed:Clonazepam, Diazepam and Lorazepamwere the benzodiazepines prescribed in the sample.

Psychotropics prescribed:

Antidepressants: Amitriptyline, Citalopram, Fluoxetine, Mirtazapine, Nortriptyline, Paroxetine, Sertraline and Venlafaxine were the antidepressants prescribed.

Antipsychotics: Olanzapine, Quetiapine, Stelazine and Zuclopenthixol depot were amongst the antipsychotics prescribed and Sodium Valproate as a mood stabilizer.

Other Medications Prescribed: Included the medications other than OST and psychotropic medications. These included Insulin, Bendrofluazide, Disulfiram, Metformin, Lisinopril, Omeprazole, Testosterone and Thyroxin. In previous research history of diseases related to substance use, hepatitis, abscesses and overdoses were studied but were not associated with retention [10] . But history of other medical conditions and other medications were not studied in the previous studies and a need was considered to include these variables in this study.

Did the Patient Drop out of OST: Number of patients dropped out during the study period were included after the file review. Nine Patients dropped out of total sample to 73.

History of Medical Conditions: Diabetes Mellitus, Hypertension, Hypothyroidism, Gastro Oesophageal Reflux Disease, Low Testosterone Level and Alcohol Dependence were the medical conditions included in the sample. As mention above history of diseases related to substance use, hepatitis, abscesses and overdoses were studied and were not associated with retention but history of other medical conditions was not studied before. A need was considered to include the history of medical conditions.

History of Hepatitis C Infection: History of diseases related to substance use,, hepatitis was studied but was not associated with retention. The need was considered to include this factor in this study.

Did the patient receive treatment for Hep C: This factor was included after the selection of history of hepatitis C.

DATA ANALYSIS

Data were gathered using the clinical audit tool and analyzed using the statistical program SPSS22.For statistical purposes, variables were divided into two categories; continuous and categorical variables. For continuous variables such as age, mean and standard deviations were calculated. A t-test was conducted for continuous variables to compare those who dropped out with those who remained in the program. For categorical variables such as gender, a frequency percentage was calculated. Fisher’s exact test was conducted for categorical variables rather than Pearson’s chi-square test because of the low numbers of dropouts. Using the t-test and Fisher’s exact test, a p value of <0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Out of the total sample, n=150, nine patients dropped out of treatment while 64 patients who were randomly selected from the remaining sample stayed on treatment during the study period.

Demographic Factors and Dropout

The mean age of the sample was 43.6 years (range 27-62 years). Men constituted 59% of the sample. Maori constituted 8% of the sample. No Maori dropped out, while 9% of the stayers were Maori. In the whole sample group, 52% were single, 15% were married and 33% were in de facto relationships.

As can be seen in Table 1, there were no significant differences in the variables between the dropout subjects and those who stayed. In other words, demographic factors were not shown to be related to patient dropout.

|

Variables |

Whole Sample % |

Dropout % n=9 |

Stayer % n=64 |

Fisher’s exact p value |

|

Age under 50 |

48 |

56 |

47 |

0.45 |

|

Gender - % Male |

|

|

|

|

|

Ethnicity- Maori % |

|

|

|

|

|

Relationship status - % Single |

|

|

|

|

|

Employment status - % Employed |

|

|

|

|

|

Living status - % Living alone |

|

|

|

|

Table 1: Demographic variables of whole sample n=73 and comparison between dropouts and stayers.

History Factors and Dropouts

History of Imprisonment

Twenty-six per cent of the sample had a history of imprisonment. Amongst the dropouts, 56% had a history of imprisonment compared to 22% of stayers (Fisher’s exact p=0.05). This difference is at the threshold level for statistical significance.

History of Intravenous Drug Use

Eighty-nine per cent of the sample had a history of intravenous drug use. Amongst the dropouts, 67% had a history of intravenous drug use compared to 92% of stayers. Fisher’s exact p value of 0.05 is at the threshold level for statistical significance. As can be seen in Table 2, there were no significant differences in the variables between the dropout subjects and those who stayed, except two: a history of imprisonment and history of intravenous drug use, which were at the threshold for statistical significance (Fisher’s exact p value = 0.05).

|

Variables |

Whole Sample % |

Dropout |

Stayers |

Fisher’s exact p value |

|

% life time imprisonment |

26 |

56 |

22 |

0.05 |

|

History of Mental Illnesses |

|

|

|

|

|

History of Substance Use Disorders between 1 Jan 2013 to 30 April 2014 |

|

|

|

|

|

History of Intravenous (I/V) Drug Use IVDU |

89 |

67 |

92 |

0.05 |

|

History of Partner’s Drug Use |

8 |

11 |

8 |

0.56 |

|

Partner on OST |

7 |

6 |

11 |

0.49 |

|

History of Hospitalisation for Alcohol and Drug Treatment between 1 January 2013 and 30 April 2014 |

8 |

0 |

9 |

0.44 |

|

History of Medical Conditions |

48 |

56 |

67 |

0.37 |

|

History of Hepatitis C infection between 1January 2013 and 30 April 2014 |

41 |

22 |

44 |

0.20 |

|

Patient received treatment for Hepatitis C before 30 April 2014 |

7 |

11 |

6 |

0.49 |

Table 2: clinical variables of whole sample and comparison between dropouts and stayers.

Results of medications prescribed and urine drug testing in dropouts

Opioid type prescribed during the study (before 30-4-2014)

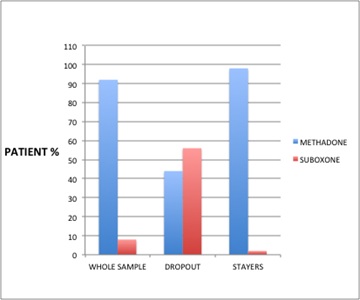

Methadone and Suboxone were used as an opioid substitute treatment in the study. Only 8% of the samples were prescribed Suboxone. Amongst the dropouts, 56% were on Suboxone compared to 2% of stayers. This difference was statistically significant (Fisher’s exact p=0.00). The result showed the patients on Suboxone were more prone to drop out than those on methadone, as shown in (Figure 1). Methadone was more effective in retaining patients on OST. This finding is consistent with some existing literature.

Figure 1: The proportion of patients prescribed methadone or suboxone opioid dose during the study.

Figure 1: The proportion of patients prescribed methadone or suboxone opioid dose during the study.

A low dose was defined as “less than 60 mg of methadone or less than 16 mg of Suboxone”. Twenty-five per cent of the sample was prescribed a low dose of opioids. Amongst the dropouts, 33% were on low doses of opioids compared to 23% of stayers. This finding was not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact p=0.39). A relationship between dose of OST and dropout was not evident. However previous study reported higher dose of Methadone was associated with retention. High dose of Suboxone was from 16 mg daily to 32 mg daily. Previous study [11] reported average dose of 10 mg of Suboxone (range 2-24 mg) was associated with retention for 24 months. There were small numbers of patients on Suboxone in this study however the result was not statistically significant Table 3.

|

Opioid type before 30-4-2014 |

Whole Sample % |

Dropout % |

Stayers |

Fisher’s exact p value |

|

% Suboxone |

8 |

56 |

2 |

0.00 |

|

Opioid dose before 30 April 2014 |

|

|

|

|

|

Were any benzodiazepines prescribed on 1 January 2013 |

15 |

11 |

16 |

0.59 |

|

Benzodiazepines prescribed after 1 January 2013 |

23 |

22 |

23 |

0.65 |

|

Benzodiazepines prescribed on 30 April 2014 |

14 |

11 |

14 |

0.64 |

|

Other psychotropic medications prescribed on 1 January 2013 |

21 |

11 |

22 |

0.41 |

|

Other psychotropic medications prescribed after 1 January 2013 |

40 |

33 |

41 |

0.49 |

|

Psychotropicmedications prescribed on 30 April 2014 |

30 |

33 |

30 |

0.56 |

|

Other medications prescribed on 1 January 2013 |

16 |

44 |

13 |

0.04 |

|

Other medications prescribed on 30 April 2014 |

18 |

33 |

16 |

0.20 |

|

UDR Variables |

|

|

|

|

|

Urine Drug Results in January 2013 |

48 |

67 |

45 |

0.20 |

|

Urine Drug Results after January 2013 |

92 |

89 |

92 |

0.56 |

|

Urine Drug Results negative for illicit drugs in all of the 3 samples, (at the baseline, during and end of the study). |

25 |

11 |

27 |

0.29 |

Table 3: Medications prescribed and urine drug results in dropouts and stayers.

Other medications prescribed at the baseline

Other medications were other than OST and psychotropic medications. These included Insulin, Bendrofluazide, Disulfiram, Metformin, Lisinopril, Omeprazole, Testosterone and Thyroxin. Sixteen per cent of the samples were prescribed other medications. Amongst dropouts, 44% were prescribed other medications compared to 13% of stayers. This difference was statistically significant (Fisher’s exact p=0.04). This finding suggests that patients who were prescribed other medications had a higher probability of dropping out.

SUMMARY OF POSITIVE FINDINGS

In summary, four variables were observed to be associated with dropout from treatment. These included other medications prescribed at the base line and opioid type prescribed during the study: patients on Suboxone were more at risk of dropout than those on methadone. A history of imprisonment and a history of intravenous drug use were the other two variables found to be associated with dropout from treatment.

DISCUSSION

In previous studies, the OST retention rate varied markedly found a retention rate of 61% after 12 months on OST. In this study, the retention rate was 94% and the dropout rate was 6% after 15 months on OST, which was lower than those found in overseas studies, reflecting the success of the OST programme in New Zealand. One possible explanation could be the effective clinical case management of OST patients in New Zealand. Most commentators also note that New Zealand does not get much imported high-quality heroin to tempt people into relapse. Service factors, which may have contributed to improved retention, were not explored in this study and could be a topic for future research. In this study Methadone was more effective in retaining the patients on OST than buprenorphine that was shown in previous studies [12]. A history of intravenous drug use was found to be associated with dropout in this study, which supports the finding of previous studies [13].

Methodological Issues and Limitations of the Study

Only those factors which were able to be easily accessed from clinical files were included, which precluded dynamic factors such as the quality of individual therapeutic relationships and service factors, including policies related to the controlled prescription of the opioid medications and specifically the opportunities for takeaway doses. Another limiting factor was the small number of dropouts (nine), during the study period.

Some of the factors included in the study such as the history of ASPD, were under represented in the sample. This study found no one with the diagnosis of ASPD. There was no significant association found between the antisocial personality traits and drop out which was not supportive of the previous studies. It needs to be further explored in future studies.

REFERENCES

- Adamson S, Todd FC, Sellman JD, Huriwai T, Porter J, et al. (2006) Co?existing psychiatric disorders in a New Zealand outpatient alcohol and other drug clinical population. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 40: 164-170.

- Vihang N (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5: A quick glance. Indian J Psychiatry 55: 220-223.

- Ausubel DP (1996) The Dole-Nyswander Treatment of Heroin Addiction. JAMA 195: 949-950.

- Bell J, Mutch C (2006) Treatment retention in adolescent patients treated with methadone or buprenorphine for opioid dependence: a file review. Drug Alcohol Rev 25: 167-171.

- Favrat B, Rao S, Connor PG, Schottenfield R (2002) A staging system to predict prognosis among methadone maintenance patients, based on admission characteristics. Subst Abus 23: 233-244.

- Finch JW, Kamien JB, Amass L (2007) Two-year experience with buprenorphine-naloxone (Suboxone) for maintenance treatment of opioid dependence within a private practice setting. J Addict Med 1: 104-110.

- Gaughwin M, Solomon P, Ali R (1998) Correlates of retention on the South Australian Methadone Program 1981-91. Aust N Z J Public Health 22: 771-776.

- Kwiatkowski CF, Booth RE (2001) Methadone maintenance as HIV risk reduction with street-recruited injecting drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 26: 483-489.

- Mertens JR, Weisner CM (2000) Predictors of substance abuse treatment retention among women and men in an HMO. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24: 1525-1533.

- Mullen L, BarryJ, Long J, Keenan E, Mulholland D, et al. (2012) A national study of the retention of Irish opiate users in methadone substitution treatment. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 38: 551-558.

- Simpson DD (1979) The relation of time spent in drug abuse treatment to post treatment outcome. American Journal of Psychiatr 136: 1449-1453.

- Simpson DD, Savage LJ, Lloyd MR (1979) Follow-up evaluation of treatment abuse during 1969 to 1972. Archives of General Psychiatry 36: 772-780.

- Ward J, Hall W, Mattick RP (1999) Role of Maintenance Treatment in opioid dependence. Lancet 353: 221-226.

Citation: Akhtar S, Sellman D, Adamson S (2019) Patient Dropout from Opioid Substitution Treatment. J Alcohol Drug Depend Subst Abus 5: 011.

Copyright: © 2019 Akhtar S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.